The origins of tarot cards can be traced to 15th-century Europe, specifically in Italy, where they were originally created as playing cards for a game called tarocchi. The earliest known tarot decks, such as the Visconti-Sforza Tarot, were lavishly painted and used for entertainment among the nobility. These decks did not initially have any connection to divination or occult practices. By the late 18th century, tarot began to be associated with mysticism, largely due to the writings of Antoine Court de Gébelin, who theorized that tarot cards held ancient Egyptian esoteric knowledge, a claim that lacked historical evidence but shaped their mystical identity.

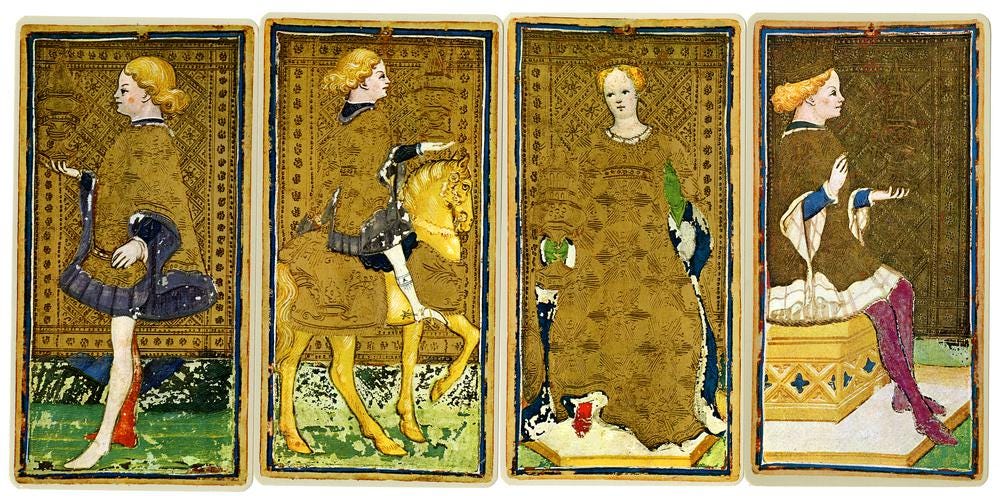

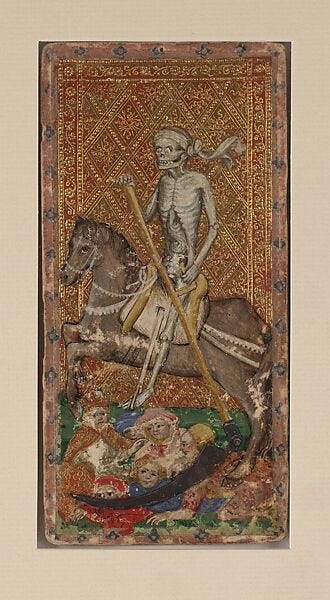

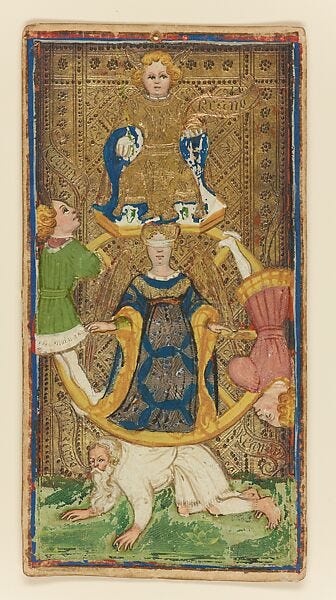

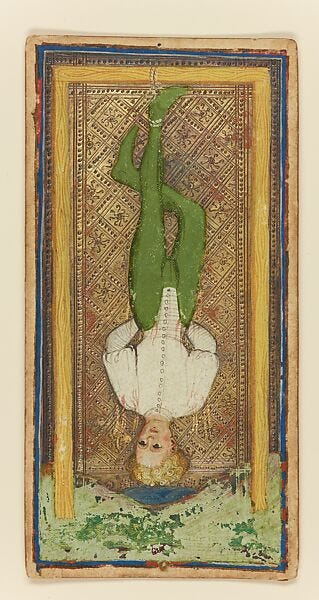

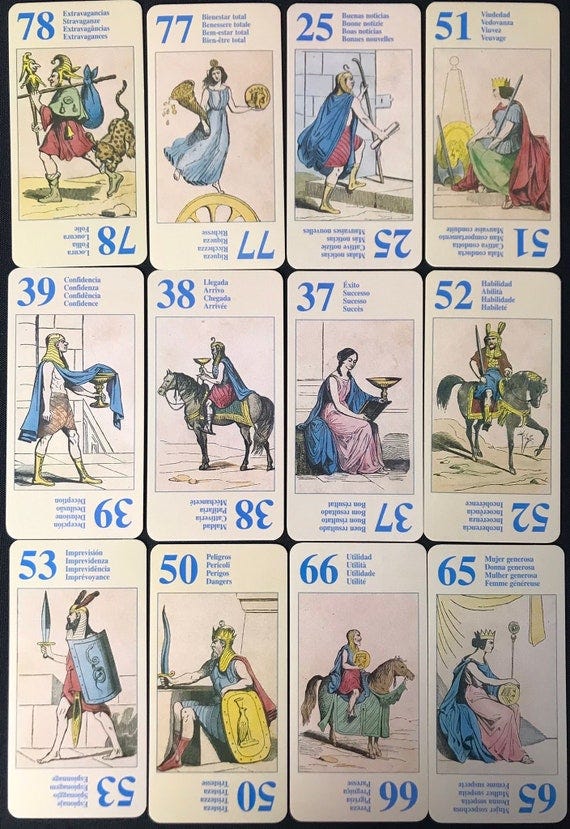

Tarot designs have evolved significantly through artistic periods. During the Renaissance, early tarot decks, such as the Visconti-Sforza, featured hand-painted images with intricate gold and silver details, drawing heavily from Renaissance humanism and Christian iconography. The figures often reflected themes of virtue, morality, and cosmology. In the Baroque period, though tarot designs were less prominent, they reflected the dramatic flair of the time. Imagery became more theatrical, with dynamic poses and a heightened use of chiaroscuro. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Art Nouveau styles dominated, exemplified by the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot (1909). Illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith, this deck’s intricate linework and symbolic depth revolutionized tarot design, emphasizing allegory and narrative.

Several artists have shaped tarot’s evolution. Bonifacio Bembo, credited with the design of the Visconti-Sforza Tarot, merged Gothic and early Renaissance aesthetics, emphasizing ornate detail and religious iconography. In the 18th century, Etteilla (Jean-Baptiste Alliette) was among the first to create tarot decks explicitly for divination, integrating astrology and alchemical symbolism that influenced later occultist decks. In the 20th century, Pamela Colman Smith, collaborating with Arthur Edward Waite, designed the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, which became the standard for modern tarot decks. Her work drew inspiration from medieval woodcuts, mysticism, and folk tales. Aleister Crowley and Lady Frieda Harris created the Thoth Tarot (1944), which blended Egyptian, Kabbalistic, and Hermetic imagery with surrealist influences.

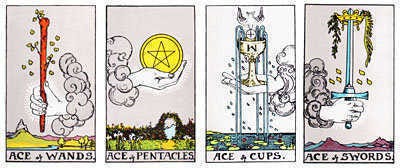

The Major Arcana and Minor Arcana reflect cultural and religious beliefs of their times. The Major Arcana contains themes such as The Pope, The Empress, and The Devil, which symbolized ecclesiastical power, natural forces, and moral struggles, reflecting medieval Christian worldviews. The Minor Arcana suits (Cups, Swords, Pentacles, and Wands) represented aspects of human life and mirrored societal hierarchies and economic systems. In the 18th century, the shift toward occult symbolism introduced esoteric systems like astrology, Kabbalah, and alchemy into tarot imagery, aligning cards with broader spiritual frameworks.

While tarot’s association with divination solidified in the 18th century, it has also been celebrated as a form of art. The elaborate craftsmanship of historical decks like the Visconti-Sforza elevated them as collectible objects, while modern decks have embraced artistic experimentation. For example, Salvador Dalí’s tarot deck combines surrealist elements with classical motifs, emphasizing the creative potential of tarot beyond divination.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, occultists like Court de Gébelin, Eliphas Lévi, and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn reinterpreted tarot as a tool for spiritual insight. This era saw the proliferation of esoteric tarot decks, such as the Rider-Waite-Smith and Thoth, which integrated Hermetic and Theosophical principles. The artistic focus shifted to symbolism that conveyed mystical truths, with imagery designed to evoke introspection and spiritual transformation.

Modern tarot decks often deviate from traditional designs, reflecting diverse cultural and artistic movements. Decks like the Wild Unknown Tarot incorporate minimalist and nature-inspired aesthetics, while others celebrate marginalized identities, such as the Next World Tarot, which emphasizes social justice. These variations highlight tarot’s adaptability as both a spiritual and artistic medium.

The same card can vary significantly in design across decks, revealing the artistic and cultural contexts of their creators. For example, The Fool in the Rider-Waite-Smith deck symbolizes naive optimism, depicted as a carefree figure on the brink of a cliff, while in the Thoth Tarot, it embodies cosmic potential, portrayed with abstract and vibrant imagery. These differences reflect shifts in artistic intent and cultural values.

Tarot decks influenced the development of modern playing cards. The four suits of the Minor Arcana evolved into the suits used in contemporary card games, and the court cards (Page, Knight, Queen, King) inspired the hierarchy of face cards. This connection underscores tarot’s historical roots in gaming before its mystical associations emerged.

Artists like Salvador Dalí used tarot as a medium to explore surrealism and symbolism. Dalí’s deck, for instance, merges personal iconography with archetypal tarot themes, creating a unique fusion of art and divination. Tarot’s emphasis on universal symbols and subconscious exploration aligns closely with surrealist principles, making it a compelling tool for artistic experimentation.

The evolution of tarot cards reflects a rich interplay between history, art, and culture. From their origins as Renaissance playing cards to their modern role as tools for divination and artistic expression, tarot decks have continually adapted to reflect the values and aesthetics of their times. Through their symbolic depth and visual diversity, tarot cards remain a powerful testament to humanity’s enduring fascination with art, spirituality, and the unknown.

References:

Decker, Ronald, Thierry Depaulis, and Michael Dummett. A Wicked Pack of Cards: The Origins of the Occult Tarot. Bloomsbury, 1996.

Kaplan, Stuart R. The Encyclopedia of Tarot: Volume I. U.S. Games Systems, 1978.

O'Neill, Robert V. Tarot Symbolism. Fairway Press, 1986.

Place, Robert M. The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination. TarcherPerigee, 2005.

Waite, Arthur Edward. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. William Rider & Son, 1910.

Salmon, Jessica. Pamela Colman Smith and the Art Nouveau Movement. Art History Quarterly, 2012.

Dalí, Salvador. Dalí Tarot Deck. Taschen, 2019.

I don’t know why I hadn’t realized Dali had done a deck. Now I need that one too. I have quite a collection. One not mentioned here that is an important original woodcut set that goes back centuries is the Tarot de Marseilles. They still print it on an old press wrapping deck in handmade paper and box, in limited editions. Joseph Maxwell wrote an entire divination book using numerology about it. Modern playing cards are largely from this deck.

‼️❤️🔥crazy