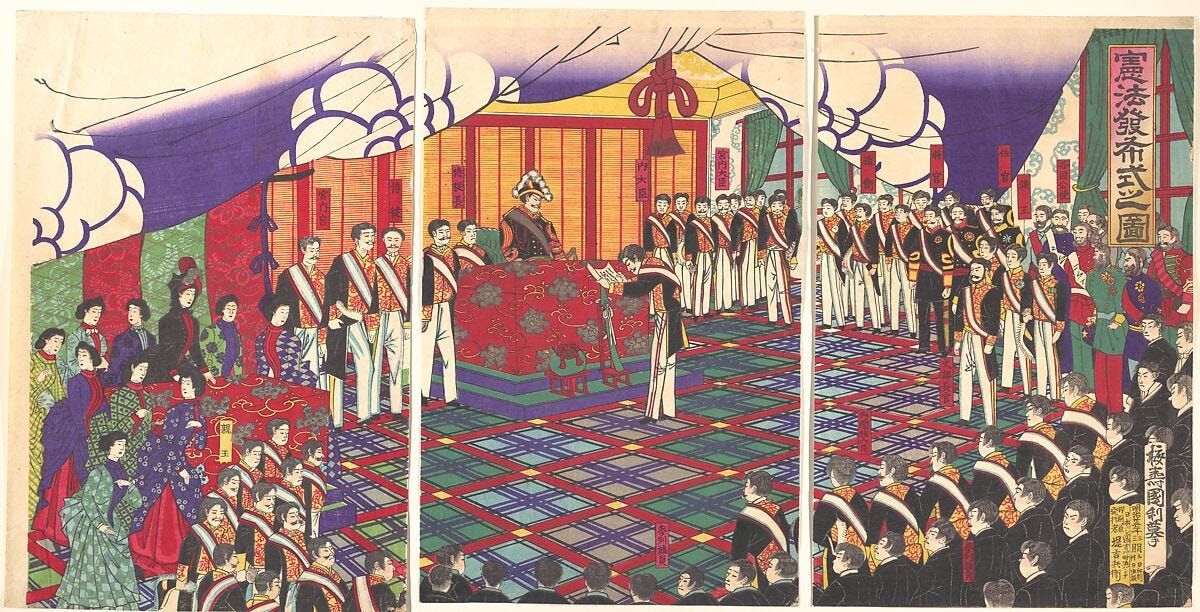

The artistic currents of East Asia in the late first millennium through the early twentieth century reveal a continuous dialogue between tradition and innovation, each school negotiating its local heritage with foreign influences. Beginning in tenth-century China, the literati painting tradition (文人画, wenren hua) united poetry, calligraphy, and ink painting into a moral and aesthetic whole; a synthesis of the “Three Perfections” that valued expressive brushwork over meticulous detail (Ashmolean Museum Blogs; Wiley Online Library). Across the East China Sea, Japan’s Meiji Restoration (1868–1912) spurred two parallel responses: Yōga (洋画), the wholesale adoption of Western oil techniques taught by foreign instructors at institutions such as the Kobu Bijutsu Gakkō (Smarthistory), and Nihonga (日本画), a self-consciously “new Japanese painting” that modernized traditional media with graded color washes and selective Western compositional devices (Conant et al.; Pigment Tokyo). In late-Qing Shanghai, meanwhile, local painters synthesized literati brushwork with popular subject matter, colorful pigments, and Western print technologies to create the vibrant Shanghai School (海上画派) that presaged twentieth-century Chinese Modernism (CoMuseum; Asia Art Collective). Together, these four movements trace a continuum of East Asian art; a testament to artists’ enduring quest to honor their roots even as they embraced new forms of expression.

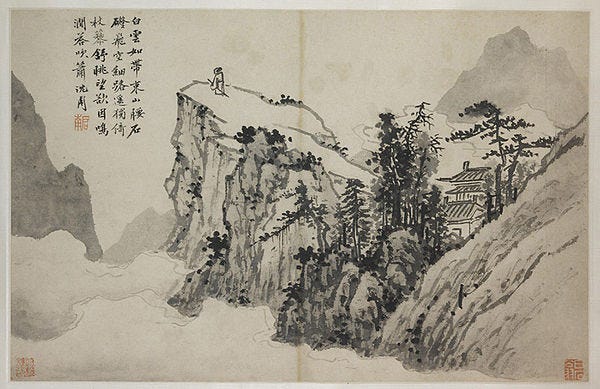

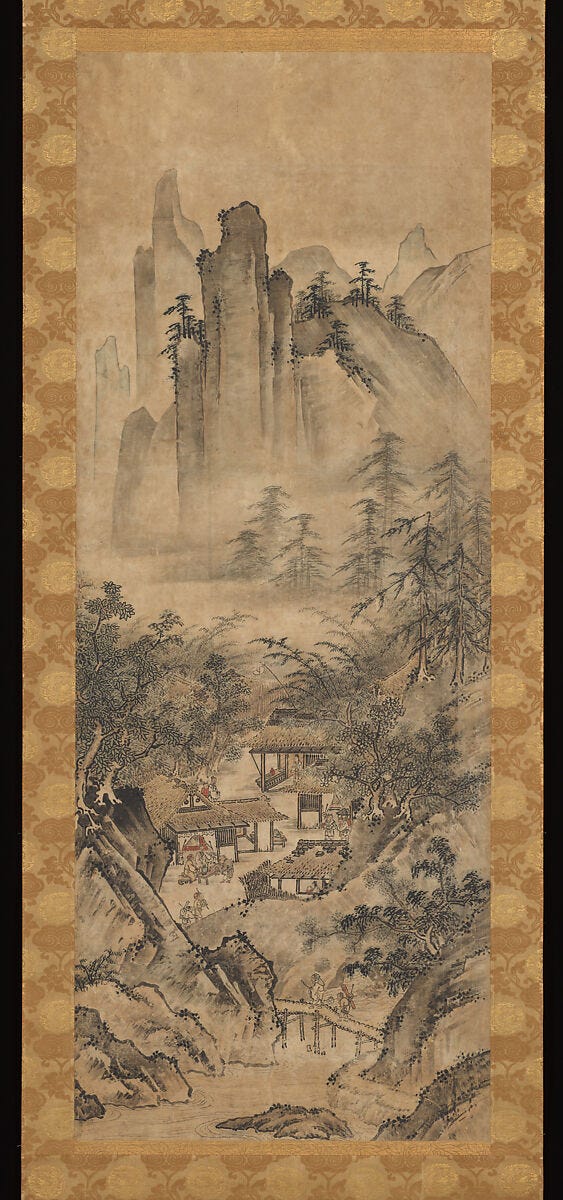

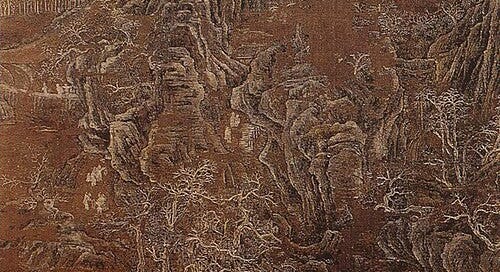

Chinese literati painting emerged during the Northern Song dynasty, when scholar-officials such as Jing Hao and Li Cheng transformed earlier Tang and Six Dynasties ink-wash experiments into monumental landscapes suffused with philosophical depth (NYU Institute of Fine Arts; Wikipedia). Rejecting the professional gongbi refinement of court ateliers, these scholar-artists practiced xieyi (“freehand”) brushwork that conveyed their inner temperament (da xin) and moral integrity, often inscribing poems directly onto their scrolls to complete the unity of painting, poetry, and calligraphy (Oakland University; Ashmolean Museum Blogs). Under Yuan rule, exiled officials like Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322) revived Tang-era models and added personal colophons to works such as Autumn Colours on the Que and Hua Mountains as a subtle assertion of cultural identity amid foreign domination (SmartHistory; Encyclopædia Britannica). In the Ming, Dong Qichang (1555–1636) codified the Southern School doctrine, extolling spontaneity and Chan-inspired sudden enlightenment as the highest ideals of literati painting (Oxford Art Online). Signature masterpieces such as Huang Gongwang’s Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, Zhao’s Autumn Colours, and Shen Zhou’s Poet on a Mountaintop, demonstrate how landscape became both a site of self-cultivation and veiled political commentary, all rendered through the “Four Treasures” of brush, ink, Xuan paper, and inkstone, and the dynamic interplay of ink and void (Wikipedia; Soper and Sickman).

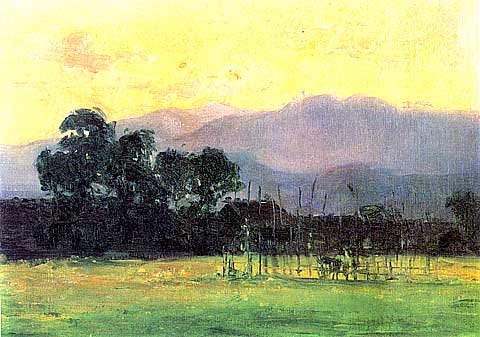

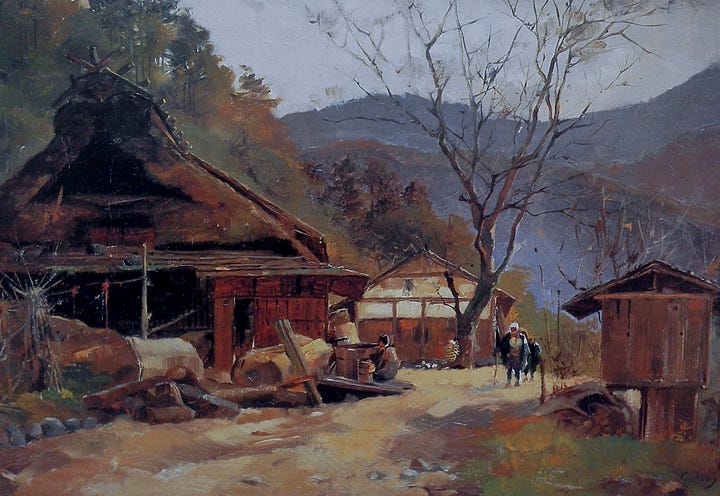

The Meiji-era Yōga movement arose as Japan’s leadership sought to modernize by importing Western academic training and plein-air practice. Under the guidance of figures such as Charles Wirgman and Antonio Fontanesi at the Kobu Bijutsu Gakkō, Japanese painters mastered linear perspective, chiaroscuro, and oil media (Smarthistory). Takahashi Yuichi (1828–1894) pioneered this style with works like Salmon (c. 1877) and Beauty (Courtesan) (1872), which display photographic realism and tonal subtlety (Smarthistory; Google Arts & Culture). His student Asai Chū (1856–1907) extended plein-air techniques to Japanese landscapes, while Kuroda Seiki (1866–1924), after Parisian training, introduced Academic Impressionism in canvases such as Lakeside (1897) that combined light-filled brushwork with formal composition (Smithsonian Institution). Societies like the Meiji Bijutsukai (1889) and the Hakuba-kai (1896), as well as the establishment of a Yōga department at the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkō (1896), institutionalized Western-style painting alongside emerging Japanese traditions (The Art Story; Pickhardt).

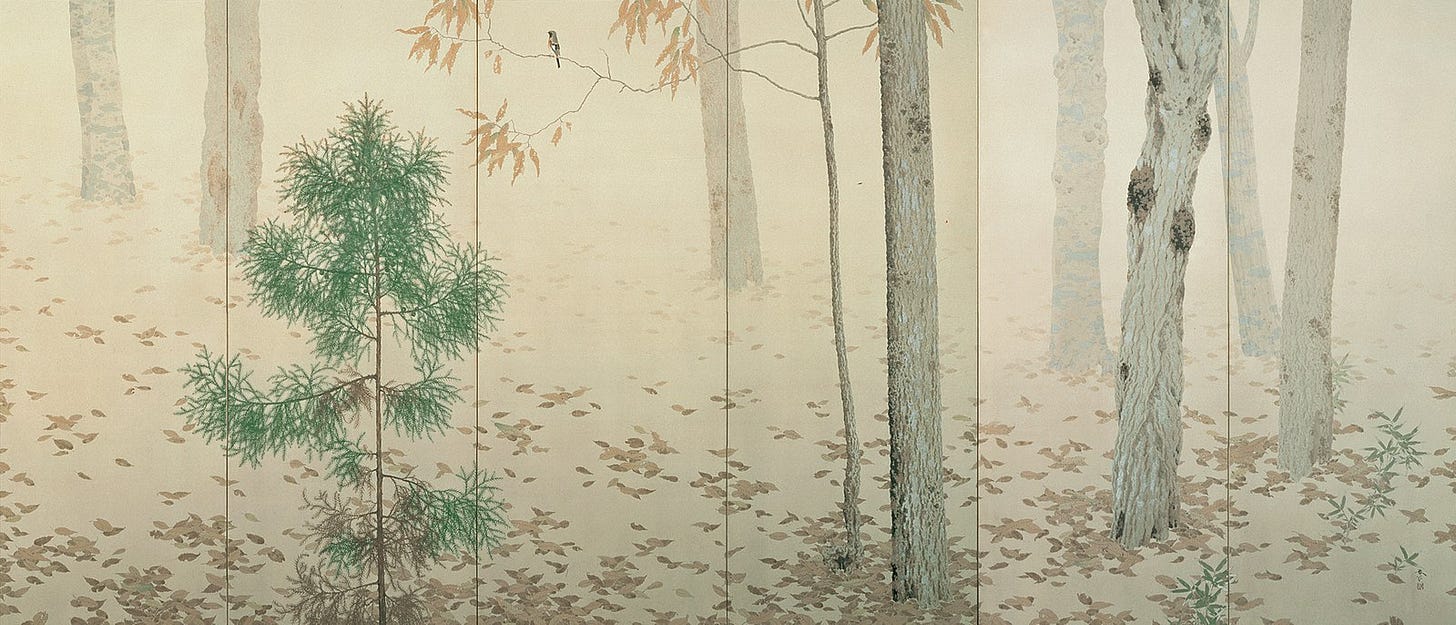

In parallel, Nihonga painters sought to modernize native techniques without forsaking their aesthetic lineage. Led by Okakura Kakuzō and Ernest Fenollosa at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and later the Japan Art Institute, artists merged mineral-pigment washes (iwaenogu) and animal-glue binders on silk or washi with compositional hints drawn from Western realism (Conant et al.; Foxwell). Innovations such as Hishida Shunsō’s graded moro-tai washes in Fallen Leaves (1909) and Yokoyama Taikan’s rhythmic expanses in Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers (1912) exemplify Nihonga’s balance of poetic flatness and atmospheric depth (Pigment Tokyo; Tokyo National Museum). Annual Bunten exhibitions and critical journals like Kokka anchored Nihonga within Japan’s cultural debates, ensuring its evolution into postwar “New Nihonga” experiments that incorporate acrylics, installation, and digital imagery (LibreTexts; The Art Story).

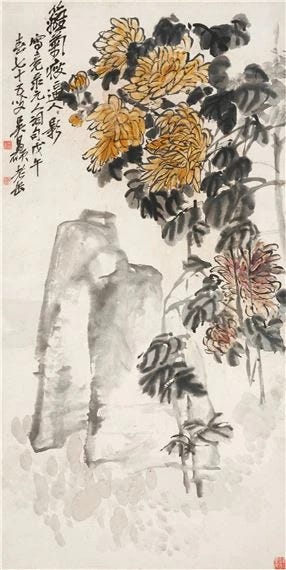

Concurrently, the Shanghai School developed in the cosmopolitan milieu of treaty-port Shanghai (c. 1870–1900), where artists such as Ren Bonian, Wu Changshuo, Zhao Zhiqian, Pu Hua, and Xugu blended literati brushwork with folk motifs, Western print aesthetics, and bold color (CoMuseum; Asia Art Collective). These painters exploited hand-colored lithography, woodblock prints, and photographic montage to reach an urban middle-class market, democratizing art consumption beyond elite salons (Long Museum). Works like Ren’s Mandarin Ducks and Lotus (1892), Wu’s Chrysanthemums and Rock (1917), and Zhao’s Flowers Album (c. 1878) testify to a hybrid visual language that retains calligraphic vigor while embracing popular narrative, thereby laying groundwork for twentieth-century Chinese modernisms such as the Lingnan School and New Ink movements (Smarthistory; Christie’s; Metropolitan Museum of Art).

From the meditative ink scrolls of China’s scholar-artists to Japan’s dual embrace of Western oils and renewed native media, and onward to Shanghai’s urban fusion of high and low art, East Asian painting in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries demonstrates an enduring capacity for adaptation and renewal. Each school, literati, Yōga, Nihonga, and the Shanghai School, responded to new social and political realities by melding inherited techniques with external influences, crafting artistic languages that remain vital today. Whether in the global resurgence of ink art or the reexamination of Meiji paintings in international exhibitions, these movements continue to inspire, proving that innovation and tradition are not opposites but partners in the ongoing story of East Asian art.

References:

Ashmolean Museum Blogs. Collecting the Past: Scholars’ Taste in Chinese Art. Ashmolean Museum Eastern Art Blog, 1 Aug. 2017, blogs.ashmolean.org/easternart/2017/08/01/collecting-the-past-scholars-taste-in-chinese-art/. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Conant, Ellen P., J. Thomas Rimer, and Stephen Owyoung. Nihonga: Transcending the Past – Japanese-Style Painting, 1868–1968. Weatherhill, 1996.

Foxwell, Chelsea. Making Modern Japanese-Style Painting: Kano Hōgai and the Search for Images. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mountains after Rain. The Met Collection, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/49154. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

National Palace Museum. Dong Qichang. theme.npm.edu.tw/exh105/dongqichang/en/index.html. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Oxford Art Online. Southern School. Grove Art Online, www.oxfordartonline.com/. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Pigment Tokyo. Iwa-Enogu, an Essential Coloring Material for Nihonga. pigment.tokyo/en/blogs/article/mineral-pigment. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Pickhardt, John R. Competing Painting Ideologies in the Meiji Period, 1868–1912. ScholarSpace, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/100831/1/Pickhardt_John_r.pdf. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Sickman, Laurence, and Alexander Soper. Eight Dynasties of Chinese Painting: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art. University Press of Hawai‘i, 1980.

Smarthistory. Meiji Period, an Introduction. smarthistory.org/meiji-period/. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Smarthistory. Zhao Mengfu, Autumn Colours on the Que and Hua Mountains. smarthistory.org/zhao-mengfu-autumn-colors-mountains/. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

The Art Story. Yōga Movement Overview. www.theartstory.org/movement/yoga-western-style-japanese-painting/. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Wiley Online Library. On the Origins of Literati Painting in the Song Dynasty. doi:10.1002/9781118885215.ch23. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Wu, Jane L. The Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty. Yale University Press, 2015.

Yang, Xin, et al. Chinese Painting Techniques: A Critical Survey. Zhejiang University Press, 2018.

Ink Wash Painting. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ink_wash_painting. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Nihonga. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nihonga. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Shanghai School (painting). Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shanghai_School_(painting). Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Wang Wei. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wang_Wei. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

Interesting to hear about all theses different schools and movements...

This took me back to my school days. I was so fortunate to have an Eastern Master come to our school for a semester. It changed how I hold the brush, load it, how I handle pigment, handle composition. It taught me how to know how little to do. When to stop.

I recommend for anyone interested in narrowing their discipline and technique to follow through with testing the examples of styles and methods here in this written piece. They may seem distant, from a far away place. Yet they are very human, and perhaps more aesthetic than anything we ever did in the west.