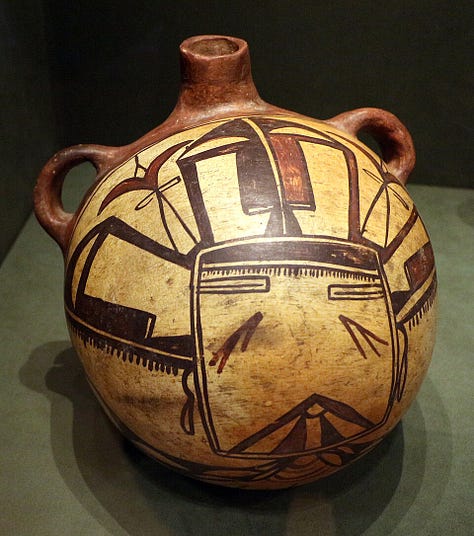

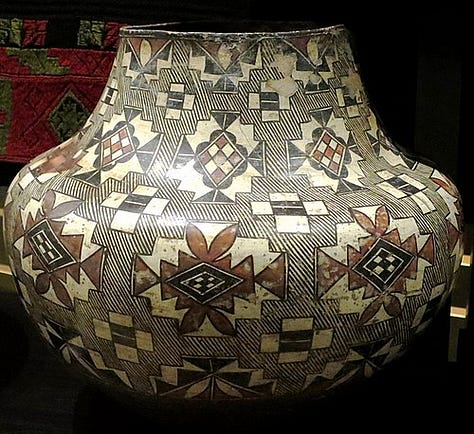

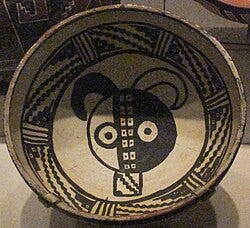

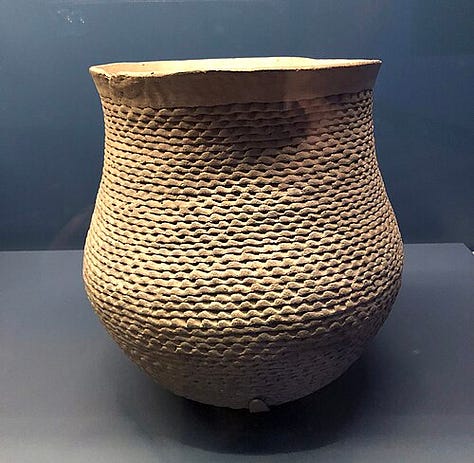

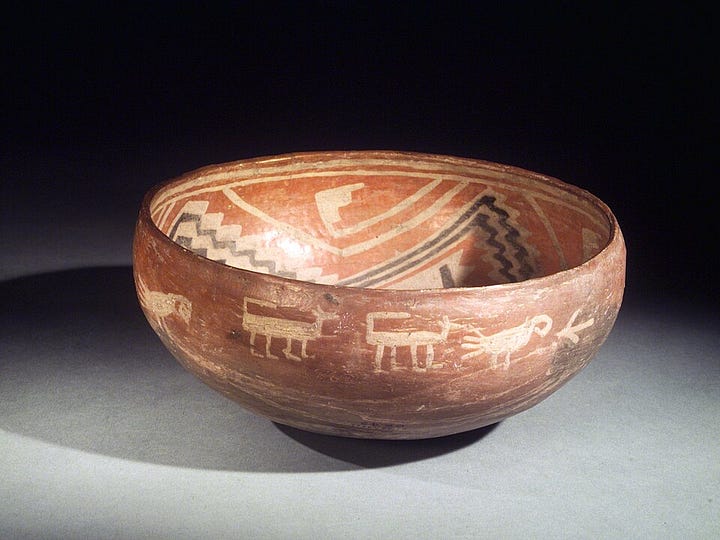

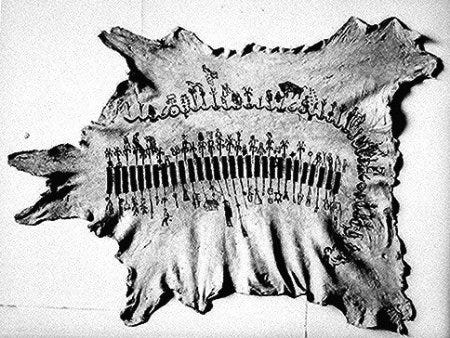

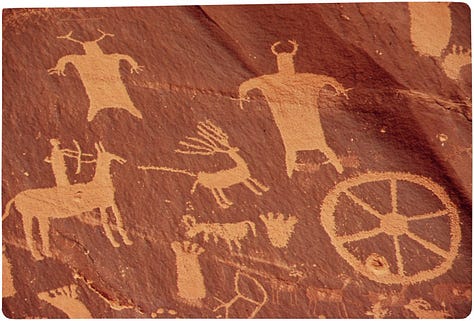

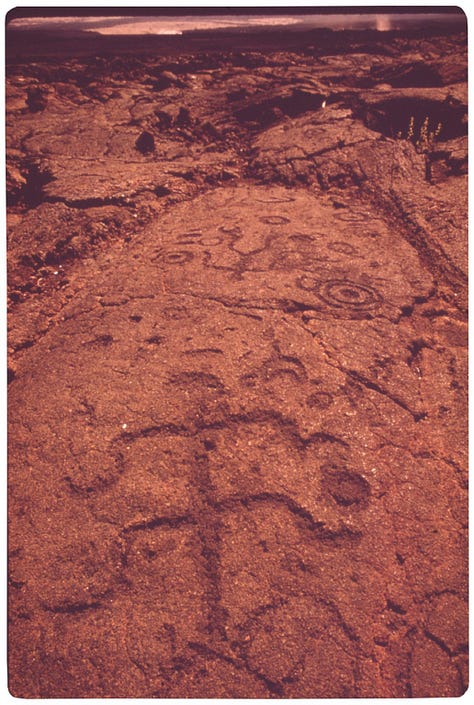

Long before European contact, the Indigenous peoples of North America produced rich artistic traditions deeply tied to their cultures and environments. There were hundreds of distinct Native American nations, each with unique forms of creative expression. Art was often utilitarian or spiritual rather than “art for art’s sake”; pottery, textiles, basketry, woodcarving, beadwork, and rock painting served practical, ceremonial, or storytelling purposes. For example, peoples of the Northwest Coast carved towering totem poles, while the Southwest’s Pueblo communities crafted intricate clay pots, and the Great Plains tribes created painted hide garments and pictographic winter counts. In these societies, no firm line separated fine art from craft; beautifully made everyday objects were as valued as any aesthetic creation. Indigenous art often carried spiritual power and connected human life with the natural world; animals, landscape features, and sacred beings were depicted to honor their significance. Though European colonization disrupted many traditions, Native American art survived and adapted. From ancient rock engravings to contemporary works by Native artists, Indigenous creativity remains a vital foundation of American art, continuously blending age-old symbols with new forms of expression.

Art in colonial America reflected both European influences and the realities of life in the New World. In the British colonies, portraiture was the dominant genre, as settler society sought to document important individuals and assert gentility through oil paintings. Early colonial painters, often self-taught or itinerant, produced relatively plain but earnest portraits. By the 18th century, however, professionally trained artists began arriving from Europe; John Smibert, for instance, settled in Newport in 1728 and brought with him academic painting skill. Following such models, colonists of means commissioned formal portraits that emulated English styles, complete with fine details of costume and setting to signify status. The first native-born American painter of great talent was John Singleton Copley, whose ambitious, realistic portraits of Boston merchants and their families in the 1760s–1770s earned him renown. Copley’s attention to minute detail and lifelike textures exemplified the colonial desire for truthful representation tempered by elegance. Other notable colonial-era artists include Benjamin West and Charles Willson Peale, who began to broaden subject matter by painting historical and revolutionary scenes as the colonies edged toward independence. Overall, colonial art was still in an early stage, relying on European conventions but laying the groundwork for a distinctly American artistic identity. Painting, along with decorative arts like silverwork and furniture-making, helped colonists express their cultural aspirations in the New World.

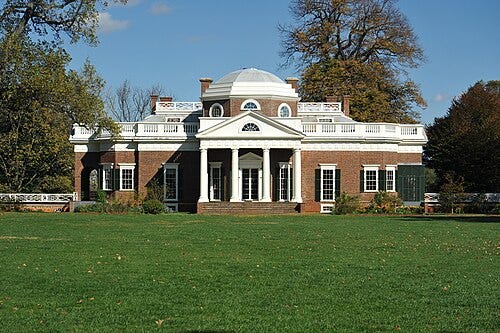

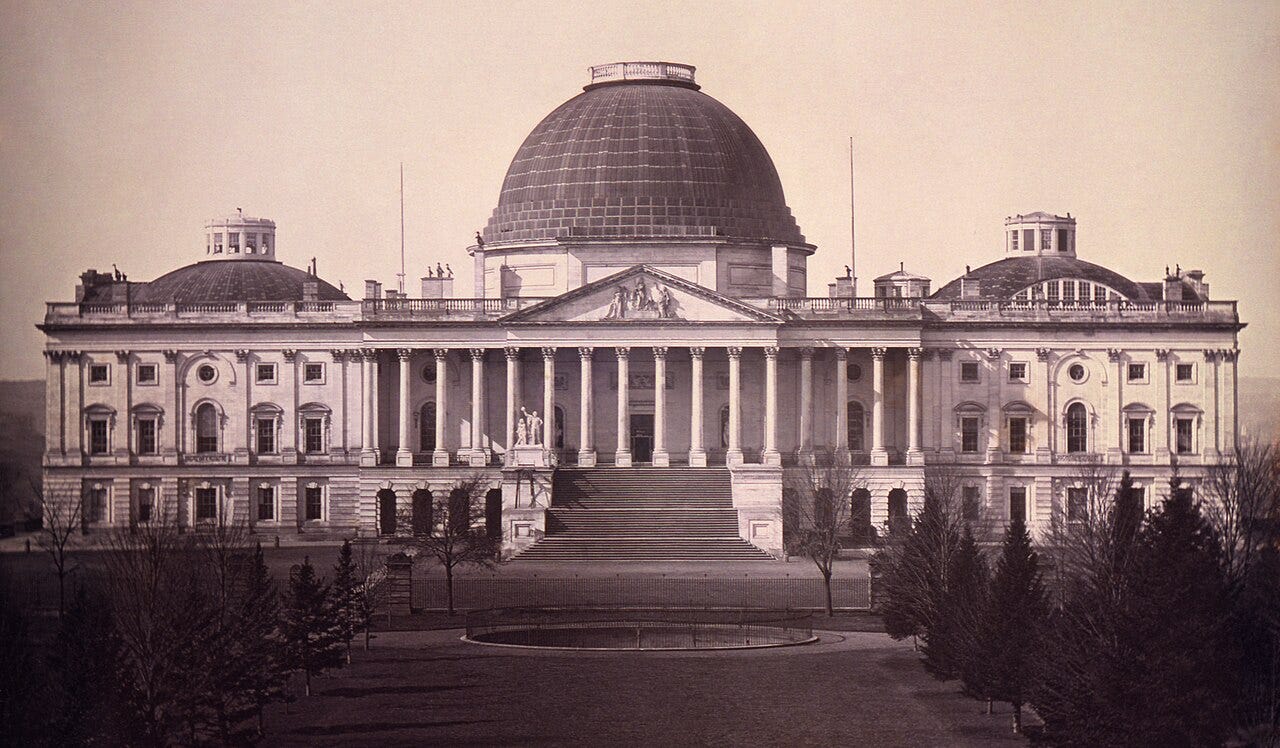

In the wake of the American Revolution, the young United States gravitated toward Neoclassicism, a style that embodied Enlightenment ideals of democracy and virtue, in its art and architecture. This era’s art is often termed the Federal style, reflecting the new Federal government and an urge to emulate classical antiquity in the arts. Portraits of Revolutionary War heroes and Founding Fathers were in high demand; for example, Gilbert Stuart’s dignified Lansdowne Portrait of George Washington (1796) became an icon of the Republic. History painting also gained prominence as artists like John Trumbull created canvases of pivotal Revolutionary moments (such as The Declaration of Independence, 1786–1820) to adorn public buildings and instill national pride. These works, with balanced compositions and idealized figures, drew inspiration from ancient Roman republican themes and the European Neoclassical style. Sculpture and architecture likewise embraced classical models, Horatio Greenough’s 1840 marble statue of Washington depicts the first president in the manner of a seated Zeus, and architects from Thomas Jefferson to Charles Bulfinch designed capitols and civic buildings with columns and pediments echoing Roman temples. American artists of the Federal period saw their work as part of the nation-building project, celebrating the new country’s leaders and democratic ideals in an “elevated” style. At the same time, more humble subjects persisted; members of the Peale family painted still lifes and everyday scenes, and itinerant folk portraitists served middle-class clients. By the 1820s, a truly national art was emerging, one that balanced European-trained sophistication with distinctly American themes of patriotism and the landscape of the Republic.

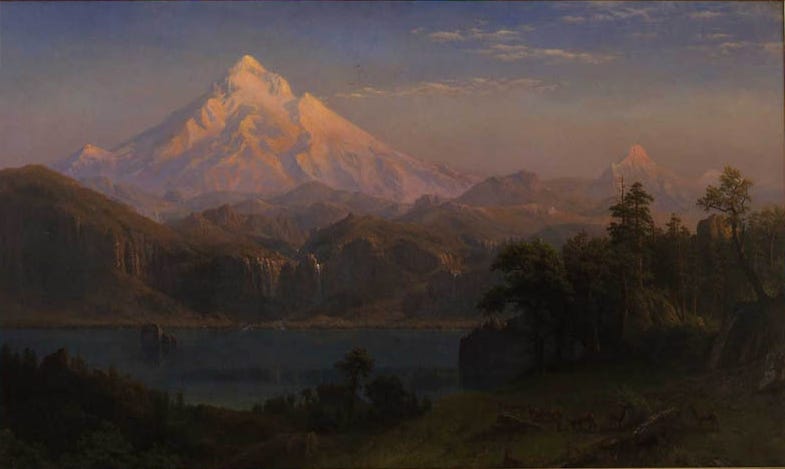

As the United States expanded in the 19th century, landscape painting became the vehicle for a proudly American vision of nature and nationhood. The Hudson River School, often considered the first native art movement in the U.S., was a loose group of painters who, beginning in the 1820s, devoted themselves to the American landscape. Founder Thomas Cole and his followers (such as Asher B. Durand and Frederic Edwin Church) sought inspiration in the scenic Hudson River Valley, the Adirondacks, and eventually the far West. They saw in America’s “untamed” wilderness a source of spiritual renewal and national destiny. Their paintings portrayed towering mountains, deep valleys, waterfalls, and dramatic skies with a meticulous realism that conveyed awe and reverence for nature’s sublime power. This art carried symbolic weight; the grandeur of American landscapes was linked to ideas of Manifest Destiny and the nation’s providential future. Typically, Hudson River School canvases are large in scale and finely detailed, inviting viewers to emotionally and intellectually immerse themselves in vistas that often dwarf any human figures present. Cole, for instance, imbued scenes like The Oxbow (1836) with allegory, showing virgin wilderness alongside cultivated land to suggest the course of civilization. A second generation of artists in the 1850s–70s, including Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, ventured beyond New York to paint the Rocky Mountains, Yosemite, and other western wonders, further reinforcing the notion that American nature was a new Eden. The Hudson River School’s blend of accurate natural detail and Romantic grandeur created a uniquely American artistic identity, one that celebrated the landscape as a reflection of national ideals and the divine.

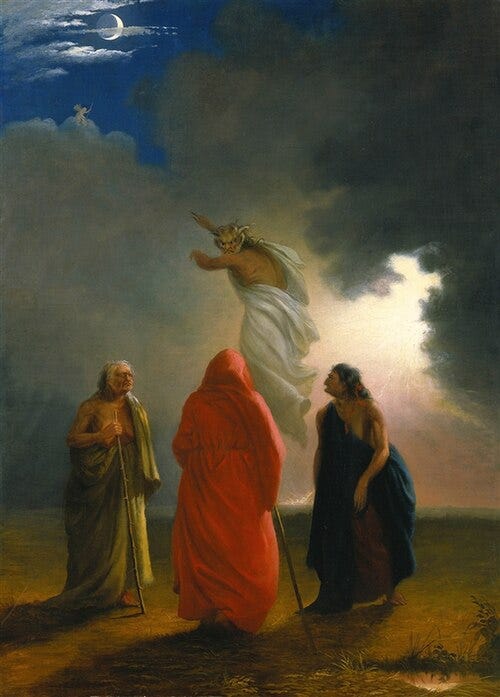

Parallel to the Hudson River painters’ celebration of landscape, American art in the mid-19th century broadly embraced Romanticism, a movement valuing emotion, imagination, and the sublime. American Romanticism found perhaps its purest expression in landscape painting, the Hudson River School itself is often considered a branch of Romantic art, but it also influenced other genres. Romantic artists were interested in conveying mood and drama, whether through nature or narrative themes. Washington Allston, for example, active in the early 1800s, was dubbed “America’s first Romantic painter” for his atmospheric biblical and literary scenes and moody landscapes. By mid-century, painters like Thomas Cole and Frederic Church not only documented nature but evoked spiritual awe and a sense of the sublime in their vistas. Typical Romantic images show tiny human figures overwhelmed by roaring storms, rugged mountains, or limitless prairies, suggesting both the terror and beauty of the natural world. In addition to landscapes, American Romanticism appeared in genre and historical painting that emphasized intense feeling, John Quidor’s depictions of Washington Irving tales, or William Rimmer’s imaginative allegories, for instance. Romantic sensibilities also meant a fascination with the exotic and past eras: painters might choose Shakespearean, medieval, or Orientalist subjects as vehicles for imaginative expression. What unified these diverse works was a rejection of calm classicism in favor of heightened emotion and individualistic vision. By the 1870s–80s, younger artists would begin to favor Realism or Impressionism, but the Romantic legacy persisted in the American imagination, having established that art should stir the spirit. In sum, American Romanticism in art suffused the 19th-century canvas with poetic feeling; nowhere more evident than in the era’s sweeping landscapes that conveyed wonder, divine presence, and the sublime on the American frontier.

Amid the grandeur of mid-century Romantic landscapes, a quieter style known as Luminism emerged, offering a more intimate approach to nature. Around the 1850s, a handful of American painters (including Fitz Henry Lane, John Frederick Kensett, Sanford Gifford, and Martin Johnson Heade) began creating landscapes on a smaller scale with an emphasis on crystalline light and tranquil atmosphere. Rather than the dramatic mountains and storms favored by the Hudson River School, the Luminists often chose serene rivers, lakes, and coastal scenes under clear skies. They rendered these scenes with meticulous, smooth brushwork, to the point that individual strokes are invisible, and a “uniform glow” of light suffuses the entire canvas. In Luminist paintings, the horizon line is typically low, yielding broad skies reflected by water, and the composition is ordered and often horizontal, imparting a sense of stillness. This measured, polished style conveyed what one historian called a “quiet spirituality” in nature, aligning with Transcendentalist ideas of finding the divine in the everyday landscape. The mood is contemplative rather than awe-struck, for instance, Kensett’s Sunset on the Sea or Gifford’s Lake George present nature as a place of peace and introspection. Human figures, if present at all, are minute and do not disrupt the scene’s tranquility. Luminism also reflected the influence of new optical ideas and even photography’s clarity, but it remained deeply rooted in painting tradition. Though never an official “school,” Luminism set itself apart from the bombast of Romantic sublime landscapes, and its legacy can be seen in later American art’s attention to light and atmosphere. These paintings of radiant skies and mirror-like waters invite the viewer to a meditative communion with nature’s subtleties.

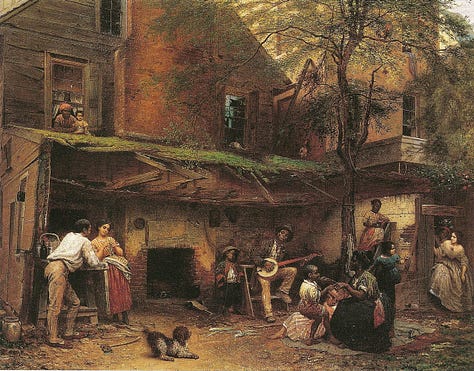

By the mid-19th century, some American artists turned from idealized or dramatic scenes to a more frank portrayal of contemporary life; a shift in step with the broader Realism movement in Europe. American Realism took hold in the years around the Civil War and after, as painters sought to depict people and scenes of everyday experience with truth and sincerity. Winslow Homer exemplifies this turn: having worked as an illustrator, he brought an unvarnished observational style to paintings of soldiers at camp and farmers in the field. During the Civil War, Homer served as an artist-correspondent and produced images like Sharpshooter on Picket Duty (1862) that conveyed the war’s realities without heroic embellishment. This documentary objectivity, akin to the new medium of war photography, distinguished his work from earlier romantic battle scenes. After the war, Homer continued to paint honest vignettes of American life, from rural schoolchildren to rugged Maine fishermen, often emphasizing humans’ humble relationship to nature’s forces. In the 1870s and 1880s, Thomas Eakins pushed Realism further with an almost scientific approach. He studied human anatomy and motion (even using early photography as a tool) to achieve unprecedented accuracy in works like The Gross Clinic (1875), which shocked viewers with its frank depiction of a live surgical operation. Eakins’ portraits and genre scenes of rowers, wrestlers, and music students likewise strove for unidealized truth and psychological depth. Other Realist painters, such as Eastman Johnson, sometimes called “the American Rembrandt”, portrayed the lives of African Americans, Civil War veterans, or everyday domestic scenes with a sympathetic, unromantic eye. What united these artists was a preference for genuine experience over grandiose themes. They often highlighted ordinary working people and social issues (poverty, racial injustice, etc.), foreshadowing the Social Realism of the 20th century. By 1900, American Realism had established that depictions of modern life, however gritty or prosaic, could be worthy subjects for fine art, breaking the domination of European historical and mythological themes. This outlook would carry forward into the urban realism of the Ashcan School in the new century.

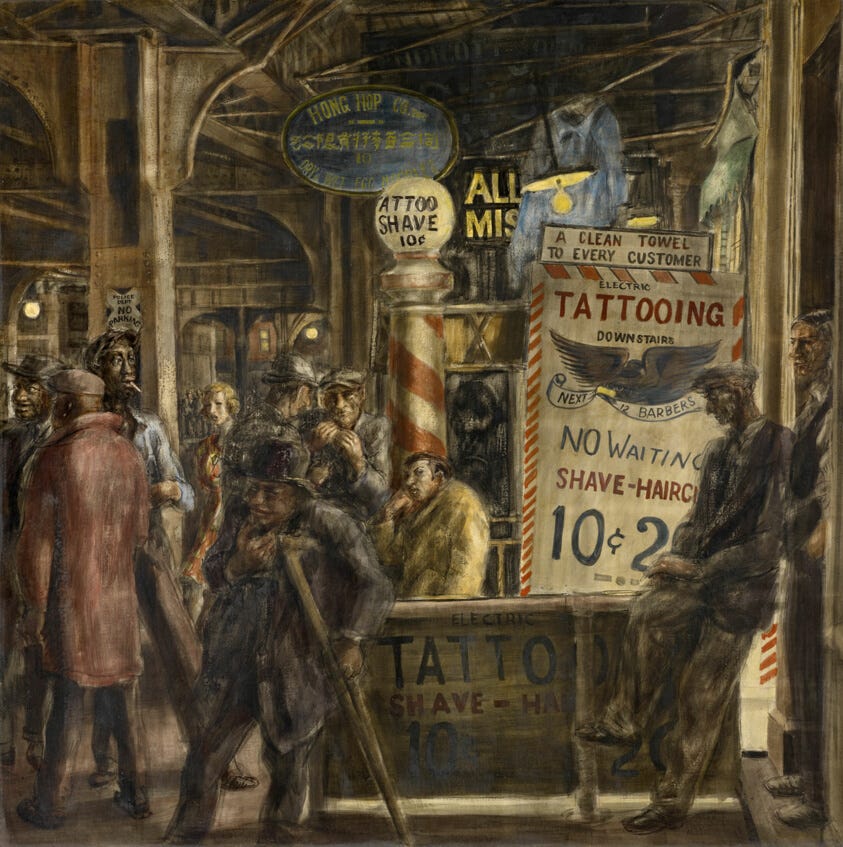

In the first decade of the 20th century, a group of rebellious American painters in New York City took Realism into the streets, determined to depict urban life with uncompromising honesty. Known as the Ashcan School, these artists, led by Robert Henri and including John Sloan, George Bellows, William Glackens, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, among others, shunned the refined subjects and impressionistic style popular in the Gilded Age. Instead, they plunged into the gritty reality of tenements, back alleys, boxing rings, barrooms, and crowded sidewalks. The Ashcan painters believed that authentic American art would only emerge by capturing the unvarnished truth of contemporary life, especially the energy and struggles of the modern city. They often worked with dark, muddy color palettes and loose, rapid brushwork, giving their canvases a rough, sketch-like immediacy that suited their subject matter. For example, George Bellows’ Stag at Sharkey’s (1909) shows two boxers flailing in a bloodied ring, surrounded by a roaring crowd; a dynamic composition of violence and vitality far removed from academic art. Similarly, John Sloan’s street scenes and tenement interiors portrayed working-class women, immigrants, and kids playing in slums with a mix of compassion and frankness. This approach was a direct challenge to the genteel American Impressionists like Mary Cassatt and Childe Hassam, who painted polished visions of urban leisure. In 1908, Henri and his circle famously organized an independent exhibition (the show of “The Eight”) after feeling snubbed by conservative juries, asserting the artist’s freedom to exhibit realist work. Though critics initially derided their paintings as “ashcan art” (suggesting they belonged in trash bins), the Ashcan School had a lasting impact. They expanded the range of acceptable subject matter in American art and set the stage for later movements concerned with social realities. Their focus on “art for life’s sake,” as Henri put it, cemented a modern aesthetic of truth and immediacy over prettiness or academic rules.

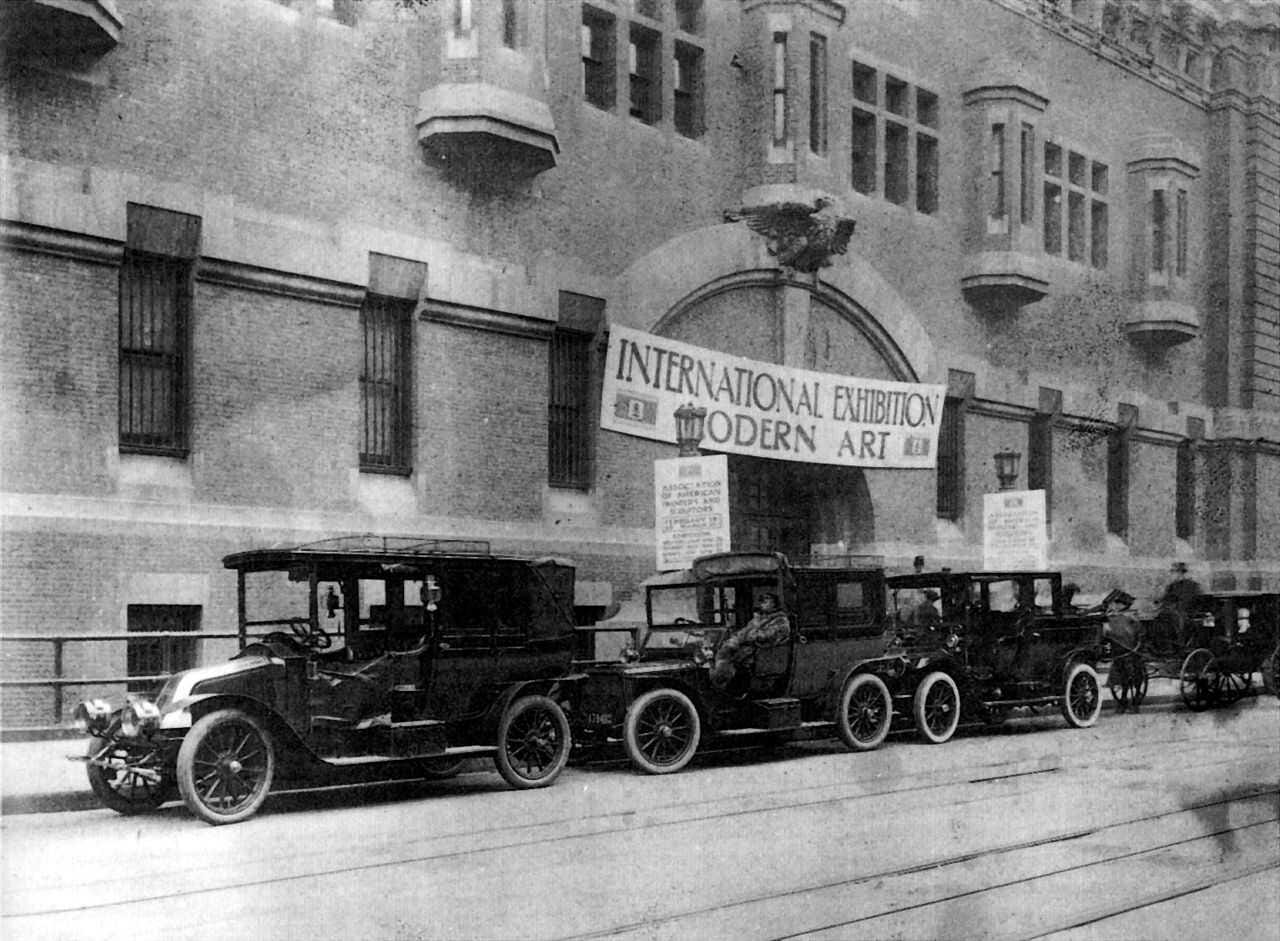

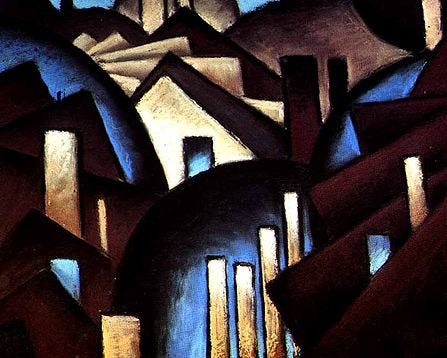

On the eve of World War I, American art underwent radical transformations as it absorbed and reinterpreted the experimental styles emerging from Europe. American Modernism in art is defined not by a single style but by a spirit of innovation and a break with tradition, roughly spanning the 1910s through the 1930s. The watershed moment was the Armory Show of 1913, which astonished American audiences with works by European avant-garde artists (from Cubists like Picasso to Fauves like Matisse) and challenged American painters to find new forms of expression. In response, American artists developed diverse modernist approaches that often combined European influences with distinctly American themes. Many modernists turned to the modern city and industrial America for subject matter, portraying the dynamism of skyscrapers, machines, and crowded streets in abstracted or boldly stylized ways. The era saw the rise of the famed Stieglitz Circle in New York: photographer and dealer Alfred Stieglitz championed emerging talents at his gallery “291.” One of these was Georgia O’Keeffe, who forged a unique modern style, simplifying natural forms into powerful abstractions; her zoomed-in flower paintings and desert bones used bold color and shape to make viewers see familiar objects anew. Other painters, like Marsden Hartley and Arthur Dove, explored early abstraction inspired by spiritual or musical analogies, while Joseph Stella captured the energy of New York in Futurist-inspired visions (e.g. his Brooklyn Bridge, 1920). Many American modernists balanced abstraction with representation: Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, for instance, created precise renderings of factories and skyscrapers with Cubist geometric order (leading into Precisionism). There was also a surge of interest in American vernacular and folk art among modernists, as seen in the appropriation of African American spirituals or Native American designs, and the Harlem Renaissance brought African American voices into the modern art scene (see below). Across painting, sculpture, photography, and design, American Modernism reflected the country’s rapid industrial growth and social change. It also marked the entry of many women and minority artists into the mainstream art world. By the 1930s, with the Great Depression, some American modernists turned their attention to public art and social issues, but the creative experimentation of the 1910s–20s laid the groundwork for the explosive developments of mid-century American art.

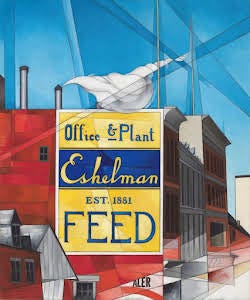

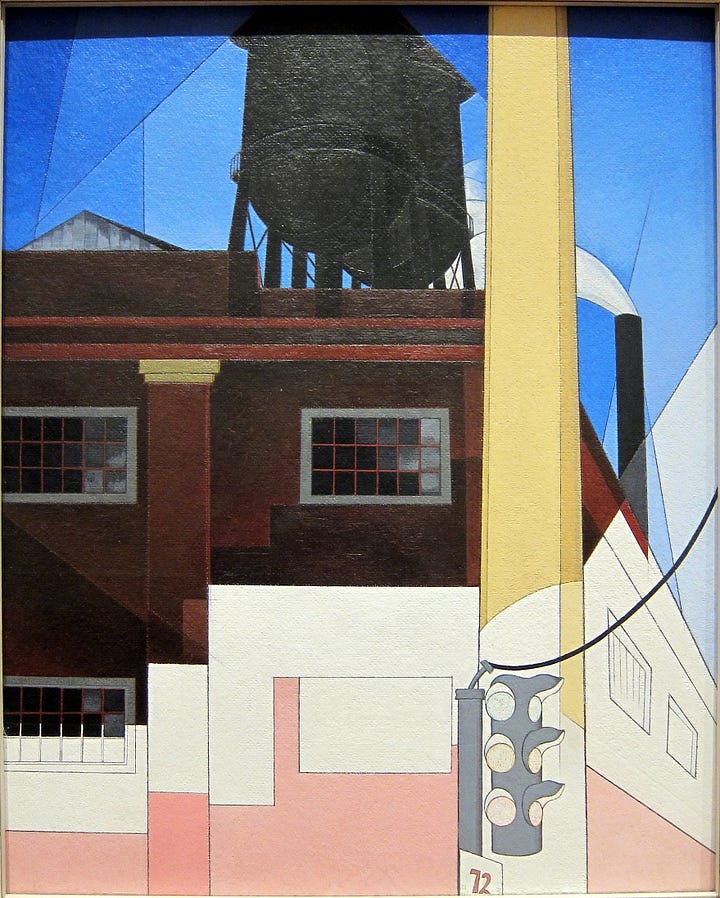

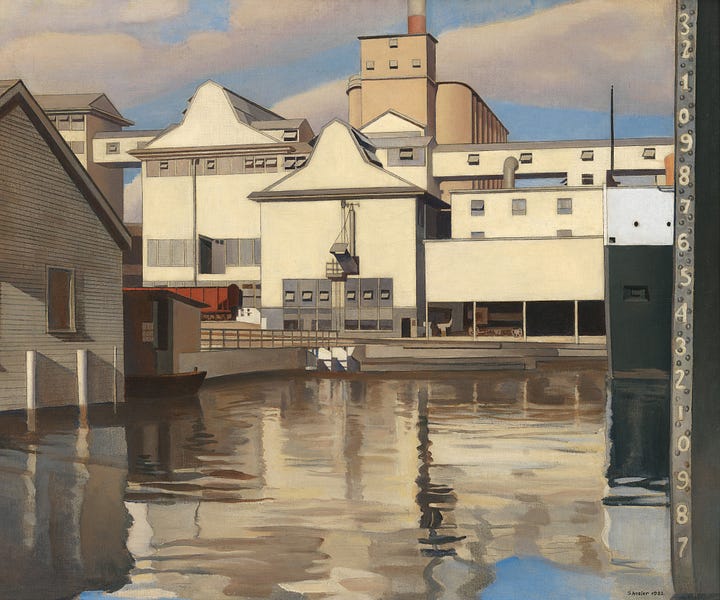

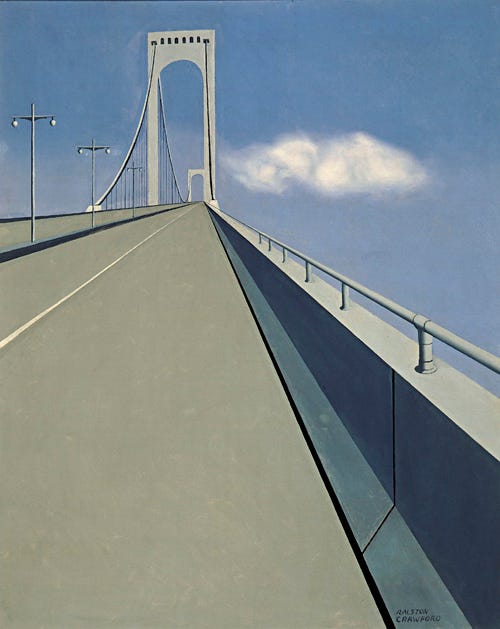

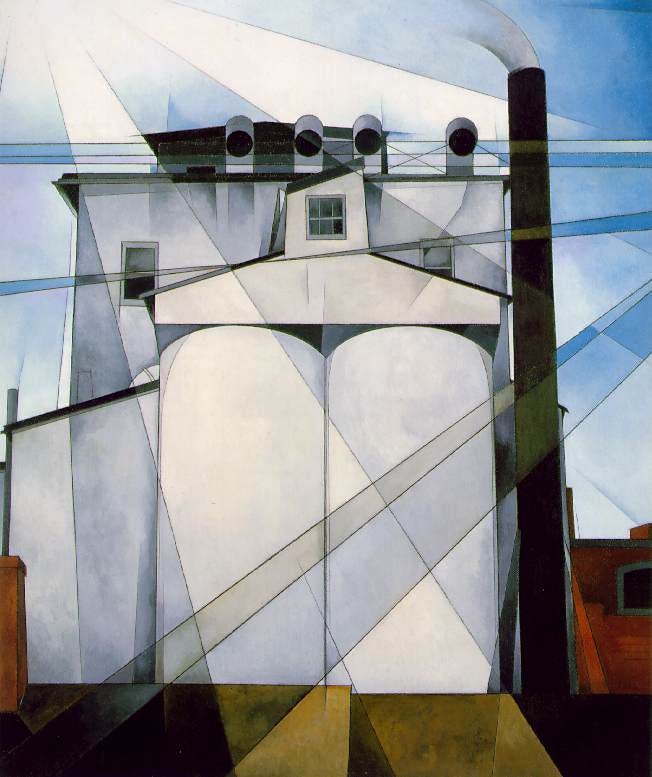

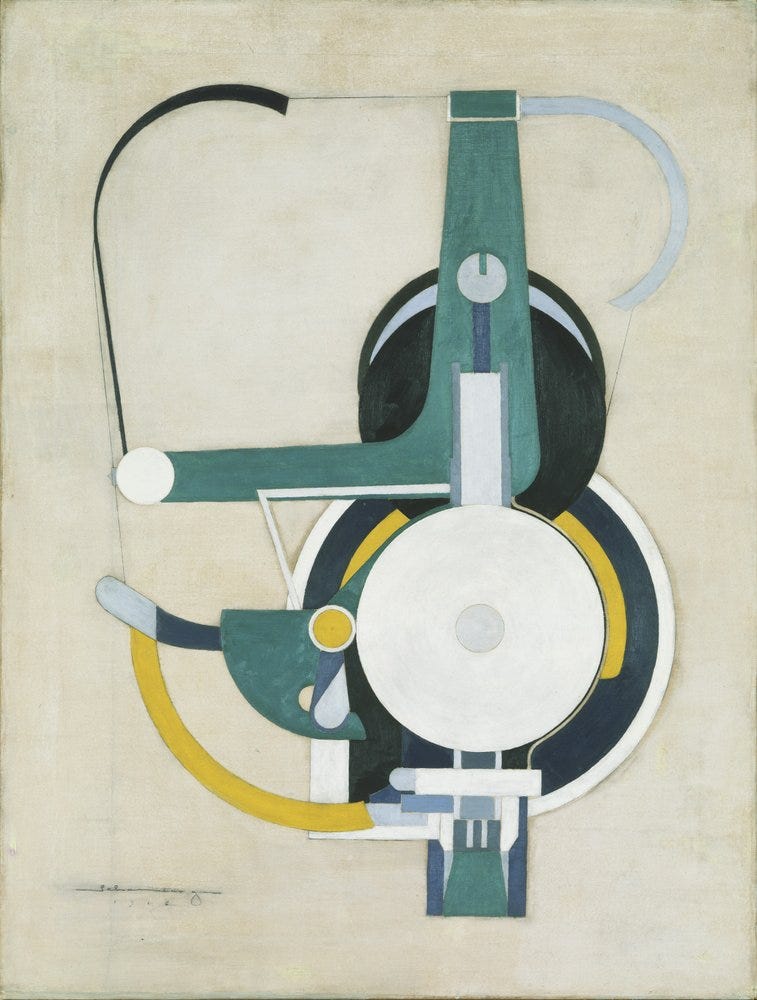

Among the various modernist currents in interwar America, Precisionism distinguished itself by its cool, streamlined celebration of the modern landscape. In the 1920s (with precedents in the late 1910s), Precisionist painters like Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth, Ralston Crawford, and others began portraying factories, skyscrapers, bridges, and industrial scenes with a sharply defined, geometric style. Their compositions reduced subjects to simple shapes and planar structures, eliminating extraneous detail and often omitting people entirely. Influenced by the clean geometry of Cubism and the dynamic energy of Futurism, the Precisionists adopted a “coolly detached” approach, part realism, part abstraction, to depict America’s burgeoning machine age. For example, Demuth’s My Egypt (1927) turns a grain elevator into a monumental, almost mystical architectural form with clear lines and gradations of light, while Sheeler’s paintings and photographs of Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant reduce the factory to interlocking shapes with an almost classical harmony. The machine was a central hero of Precisionism; these artists saw beauty in steel and concrete and often treated industrial sites as temples of modern life (indeed, Sheeler called America’s factories “our substitute for religious expression”). The style is characterized by smooth handling of paint (sometimes airbrush-like), strong contrasts of light and shadow to accentuate form, and an overall sense of order and stillness. Some works border on pure abstraction (such as Morton Schamberg’s painting of machine parts) yet typically maintain a recognizable subject. Critics noted the absence of workers or human activity in many Precisionist scenes, a choice that some interpret as commenting on the dehumanization of modern life; though generally the movement is viewed as celebratory, not critical, of industrial progress. Precisionism was relatively short-lived as a coherent trend, but it was highly influential as the first indigenous American modern art movement. Its fusion of American subject matter with modernist style prefigured later movements, and indeed the clarity and structural focus of Precisionism would echo in postwar abstraction and Pop Art. By the late 1930s, artists had largely moved on to other concerns, but the Precisionist vision had firmly asserted that the factories, skylines, and machines of America were fit muses for American art.

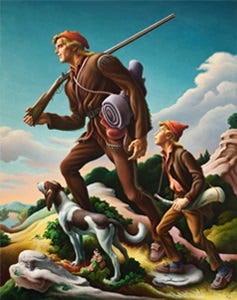

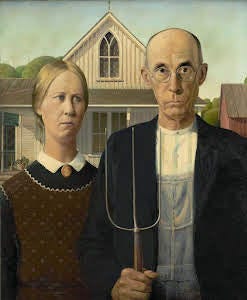

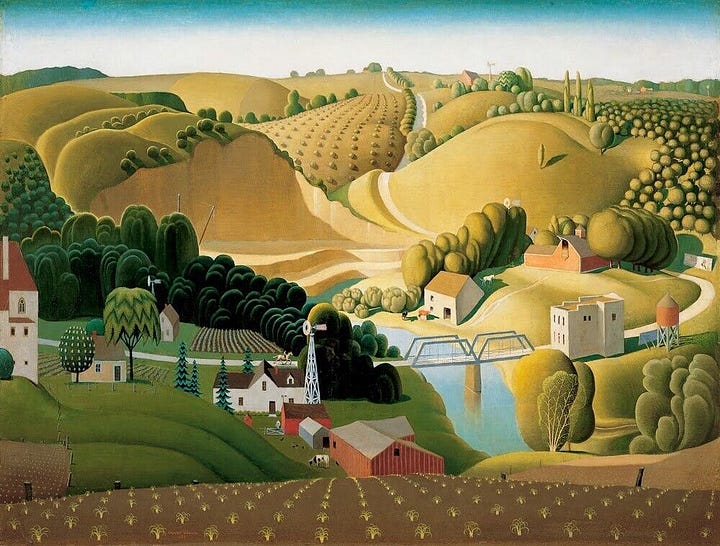

During the Great Depression, as the international art scene shifted, many American artists turned inward, seeking inspiration in the nation’s own regions and rural traditions. American Regionalism emerged in the 1930s as a celebration of the American heartland and a rejection of European modernism and big-city elitism. The movement’s leading figures, Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, Grant Wood of Iowa, and John Steuart Curry of Kansas, each painted the landscapes and people of their home states in an earthy, narrative style. Regionalist paintings were figurative, highly readable scenes of farm life, small-town events, and local folklore, rendered with clarity and often a touch of nostalgia. For example, Wood’s American Gothic (1930) depicts an upright farmer and his daughter (modeled by the artist’s dentist and sister) before a Midwestern farmhouse; a work so precisely detailed and iconic in composition that it felt at once familiar and mysterious. Such works, accessible to ordinary viewers, quickly gained popularity across America. Benton’s murals, like the America Today series (1930–31), packed entire regions and social classes into dynamic compositions, from lumberjacks and riveters to gospel preachers, insisting that all of American life, rural and urban, past and present, was intertwined in the national story. While often celebratory in tone, Regionalism was not without complexity or critique: Wood’s paintings sometimes include subtle satire or psychological tension, and Curry’s farm scenes can carry darker allegorical undercurrents (as in his tornado and prairie fire subjects). Importantly, Regionalism was bolstered by New Deal arts programs (like the WPA) that commissioned murals and artworks across the country, giving artists the chance to portray local American themes on a grand scale. Yet by the late 1930s, Regionalism faced backlash. The rise of authoritarian regimes in Europe, who used traditional realist art as propaganda, made some critics view Regionalists’ anti-modern, nationalist bent with suspicion. Moreover, the emerging generation of Abstract Expressionists in the 1940s would repudiate Regionalism as parochial and “old-fashioned” (notably, Jackson Pollock, once Benton’s student, rebelled against his teacher’s figurative style). Nonetheless, at its height, American Regionalism profoundly influenced the cultural identity of the Depression-era U.S., providing images of resilience, community, and American simplicity that resonated deeply in a troubled time.

Alongside Regionalism, the 1930s witnessed the rise of Social Realism; an art movement aligned with leftist politics and dedicated to portraying the struggles of working people during the Depression. Social Realist artists believed art should be a weapon for social change, and they depicted the “masses” (industrial laborers, poor farmers, immigrants, the unemployed) in a figurative, often narrative style that aimed to expose injustice and rouse empathy. They were inspired by earlier examples of art in the service of the people, from Goya and Courbet to the Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera. In fact, Mexican muralism’s influence was strong; Rivera’s 1930s murals in U.S. cities and the populist spirit of the Mexican Revolution helped galvanize American artists to see art as socially purposeful. Notable American Social Realists include Ben Shahn, who painted and drew searing indictments of poverty and racism (such as The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti, 1931–32), Jacob Lawrence, whose Migration Series (1940–41) epicly chronicled the experiences of Black migrants, and Philip Evergood, William Gropper, Isabel Bishop, and Reginald Marsh, among others. Their works varied in style, ranging from near-cartoon simplification to moody, expressive realism, but were united in their focus on human figures and social narratives rather than abstract experimentation. Common themes included bread lines, workers on strike, tenement life, and scenes of political protest or oppression. For example, Shahn’s Miners’ Wives (1948) portrays the anxious spouses of trapped coal miners, directly evoking class empathy. Many Social Realists were involved in labor movements or the Communist Party, and they saw themselves as worker-artists: they might even pose in overalls to signal solidarity with the proletariat. In conscious opposition to the European avant-garde, they declared that the content of art, its political message, was what made it modern and urgent, not stylistic novelty. It’s important to distinguish Social Realism from Soviet Socialist Realism: while both favored proletarian subjects, American Social Realism was not state-imposed art but rather a grassroots, often oppositional movement (indeed, many works were implicitly or explicitly critical of American capitalism and were sometimes censored or controversial). By the 1940s, as war and post-war prosperity shifted the national mood, Social Realism’s prominence waned, and many of its artists either adapted to new styles or fell into obscurity during the Cold War (when overt leftist art was viewed with suspicion). Even so, the movement left a legacy of powerful images of 20th-century American life and set a precedent for socially engaged art that would be revived in later decades.

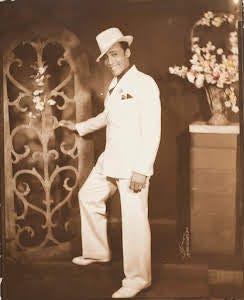

In the 1920s, New York City’s Harlem neighborhood became the epicenter of a groundbreaking African American cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance. While the Harlem Renaissance spanned literature, music, and performing arts, it also had a profound impact on the visual arts, as Black artists forged new ways to celebrate African American identity and heritage. There was no single stylistic formula for Harlem Renaissance art; instead, artists experimented with diverse techniques to express the Black experience, often blending modernist aesthetics with African or African-diasporic motifs. A key figure was Aaron Douglas, whose paintings and illustrations (for example, the series Aspects of Negro Life, 1934) employ bold, flat silhouettes and rhythmic geometric designs influenced by African sculpture and jazz music. Douglas’s work, like much Renaissance art, consciously connected contemporary Black life to ancestral African roots and to a wider narrative of history and progress. Sculptor Augusta Savage, another leader, crafted dignified busts of Black figures and founded an arts school in Harlem to nurture young talent. Photographers such as James Van Der Zee documented Harlem’s people in elegant portraits, countering racist caricatures with images of beauty and pride. The movement was originally called the “New Negro” movement, after Alain Locke’s 1925 anthology The New Negro which encouraged Black artists to look to their own culture for inspiration. Indeed, common themes included racial pride, the valorization of Black history (for example, Meta Warrick Fuller’s sculpture Ethiopia Awakening, 1921, invokes an ancient African past), and contemporary urban life from a Black perspective (as in Archibald Motley’s colorful nightclub scenes, though Motley was based in Chicago). Harlem Renaissance artists often collaborated with Black writers and musicians; their work appeared in journals and on murals, and many were employed in the 1930s by the WPA’s Federal Art Project, which funded Black artists to create public artworks in Harlem and beyond. Importantly, the Harlem Renaissance cultivated a self-conscious identity in art; rather than imitating white artists, these creators strove to depict, as painter William H. Johnson put it, “what is in me, both rhythmically and spiritually” as an African American. By the late 1930s, the Renaissance’s heyday faded due to the Depression’s hardships and the migration of many artists, but its influence endured. It paved the way for later generations of African American artists and imbued American art with rich new stories, forms, and rhythms. The Harlem Renaissance confirmed that American art was not monolithic; it was, and is, strengthened by the diverse cultural voices within it.

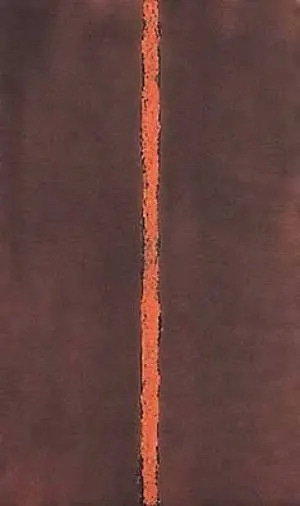

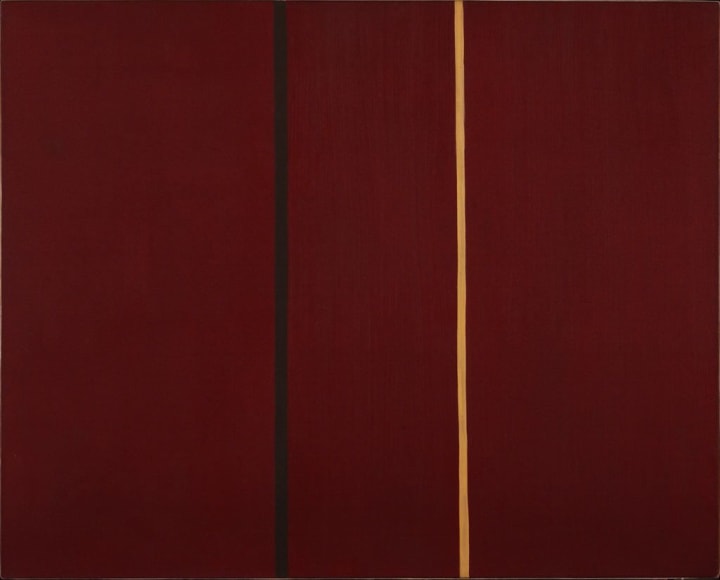

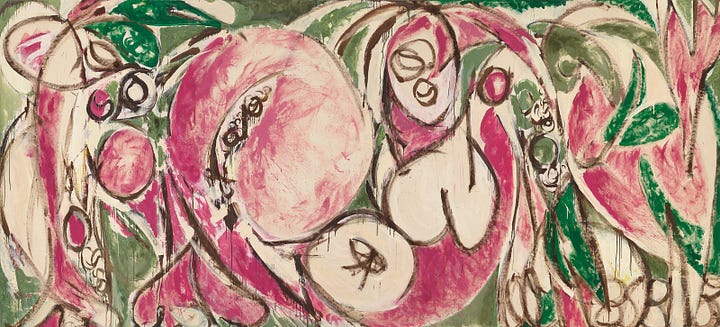

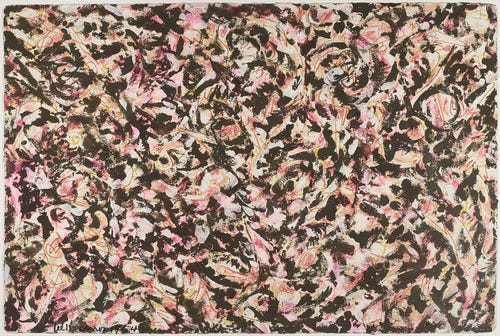

In the aftermath of World War II, American art exploded onto the international stage with Abstract Expressionism, a movement that placed New York City at the forefront of contemporary art. This loose group of artists in the 1940s–50s (often called the New York School) shared an interest in abstraction as a means of raw expression, although their techniques varied from vigorous gestural paint application to vast fields of color. Abstract Expressionism wasn’t a formal manifesto-driven movement, but the artists had in common a commitment to art as an expression of the self ; an almost spiritual channeling of inner emotion, anxiety, and imagination onto canvas. They were deeply influenced by Surrealism’s earlier focus on the unconscious mind and by the tragic mood of the post-war era; thus they treated painting as an arena for exploring universal themes like creation, destruction, angst, and redemption. There were two main tendencies within Abstract Expressionism. Action Painting, exemplified by Jackson Pollock’s famous drip paintings, emphasized the physical act of painting as an expression itself, Pollock would fling and pour paint in rhythmic motions, literally embedding his movements into the work. As critic Harold Rosenberg wrote, the canvas became “an arena in which to act… not a picture but an event”. In contrast, Color Field Painting (practiced by artists like Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still) involved large expanses of color meant to evoke contemplation or the sublime; for instance, Rothko’s floating rectangles of color were intended to elicit deep emotional or spiritual responses. Despite these differences, all Abstract Expressionists embraced large scale (their paintings are often mural-sized) and rejected traditional figurative content, pushing American art into pure abstraction unprecedented in its freedom. They also embodied a new image of the artist in American culture: the “heroic” avant-garde painter, often portrayed as a rugged, rebellious individualist (though it must be noted that women painters like Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, and Helen Frankenthaler were also significant contributors, even if history initially gave more spotlight to their male counterparts). The movement’s rise was rapid, by the 1950s, Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and their peers were internationally famous, and their success symbolized an American cultural triumph in the Cold War era. No longer provincial, the U.S. was now the leader of the art world, as the center of gravity shifted from Paris to New York. Abstract Expressionism was celebrated as profoundly “American” for its scale, its emphasis on individual freedom, and its bold break with the past. By the late 1950s the movement splintered and new styles (like Pop Art) emerged in reaction to it, but Abstract Expressionism’s impact was monumental. It demonstrated that American artists could create a new visual language, one that was abstract but emotionally immediate, and in doing so, it fulfilled a trajectory that began with earlier movements: the embrace of personal expression (“expressionism”) built on the foundations laid by centuries of American art, from Indigenous traditions to the innovations of the modern age.

Works Cited

Berlo, Janet C., and Ruth B. Phillips. Native North American Art. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Gustlin, Deborah, and Zoe Gustlin. Indigenous Art in North America (1600s–1800s). Herstory: A History of Women Artists, Open Educational Resource, Evergreen Valley College, 2020.

Jaffee, David. Art and Identity in the British North American Colonies, 1700–1776. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct. 2004.

Smithsonian American Art Museum. Early American Art – Highlights. americanart.si.edu, Smithsonian Institution, n.d.

The Art Story. The Hudson River School. The Art Story: Movements, The Art Story Foundation, n.d.

The Art Story. Romanticism. The Art Story: Movements, The Art Story Foundation, n.d.

The Art Story. Luminism. The Art Story: Movements, The Art Story Foundation, n.d.

The Art Story. American Realism. The Art Story: Movements, The Art Story Foundation, n.d.

The Art Story. American Regionalism. The Art Story: Movements, The Art Story Foundation, n.d.

The Art Story. Social Realism. The Art Story: Movements, The Art Story Foundation, n.d.

The Art Story. Harlem Renaissance Art. The Art Story: Movements, The Art Story Foundation, n.d.

The Art Story. Abstract Expressionism. The Art Story: Movements, The Art Story Foundation, n.d.

Love this piece, especially the native american influenced in the firstbpart and the later rile of the Ashcan school some favorites there. Recently talked about Philip Evergood with a friend, where he fit. New York school post Ash Can? Like Alice Neel…

This will be my coffee. Thank you for doing this one now. It feels overdue.