From Renaissance Harmony to Baroque Drama: Defining Two Transformative Eras in Art History

#FrequentlyAskedQuestions

The Renaissance is defined as a rebirth of classical antiquity and a shift towards humanistic and naturalistic art. This period flourished in Italy before spreading to Northern Europe, influencing not only painting but also sculpture and architecture. Artists combined the techniques of classical art with new innovations, resulting in a visual language that celebrated the human form, intellectual achievement, and divine beauty.

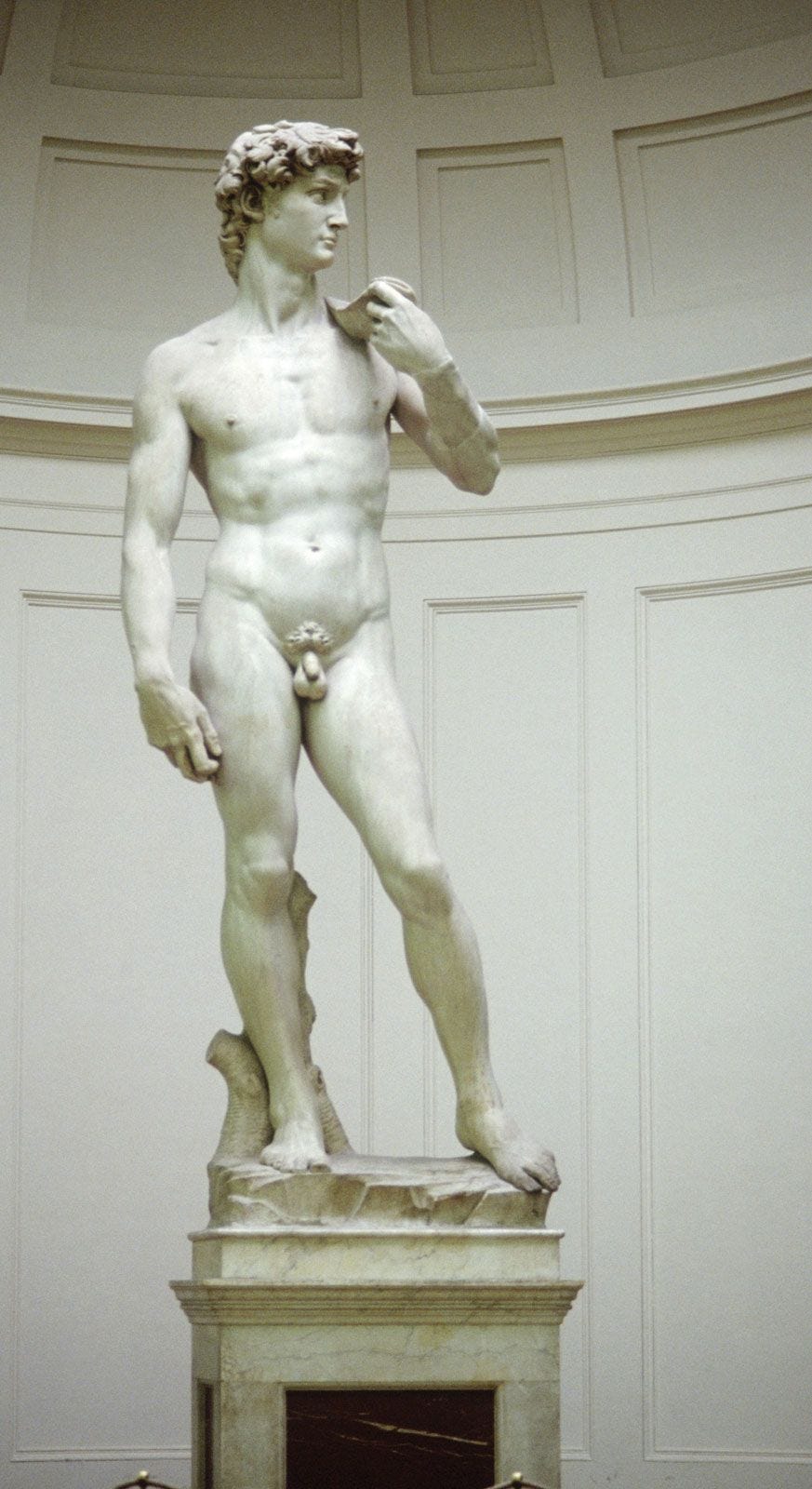

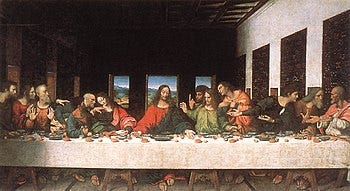

Key examples include Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1495-1498), which uses linear perspective to guide the viewer's eye to the central figure of Christ. The painting exemplifies the Renaissance's focus on proportion and symmetry, while also conveying emotional depth as each apostle reacts uniquely to the revelation of betrayal. Similarly, Michelangelo’s David (1501-1504) demonstrates anatomical precision and a shift towards portraying biblical figures with a sense of heroic dignity rather than medieval stylization (Kleiner, 2017).

In Northern Europe, Renaissance art took on a distinctive flavor, blending realism with meticulous detail. For example, Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait (1434) highlights the use of oil paints to create texture and light, from the gleam of the chandelier to the folds in the subjects’ clothing. The Northern Renaissance was less focused on classical antiquity and more concerned with religious and domestic themes, as seen in Albrecht Dürer’s engravings such as Melencolia I (1514), which incorporate symbols of intellectual and existential inquiry ("Renaissance Art," History.com).

Architectural achievements were equally transformative. Brunelleschi’s Dome (1420-1436) for the Florence Cathedral introduced innovative engineering techniques inspired by Roman architecture. Its grandeur symbolized the era’s emphasis on human ingenuity and divine order (Boucher, 2018).

Baroque art represents a dramatic and emotional response to the Renaissance’s intellectualism. While Renaissance art sought to evoke contemplation, Baroque art aimed to inspire awe and immerse the viewer. The period coincided with the Counter-Reformation, which used art as a tool for religious persuasion.

One quintessential Baroque work is Caravaggio’s The Conversion of Saint Paul (1600-1601). Through the use of tenebrism—extreme contrasts between light and shadow—Caravaggio dramatizes Paul’s divine encounter, focusing on the visceral, physical moment of his fall. Another striking example is Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-1652), a marble sculpture capturing the spiritual rapture of the saint. The interplay of light, texture, and emotion exemplifies the theatricality of Baroque art (Baroque Art, Oxford Art Online).

In painting, Peter Paul Rubens epitomized the dynamic and emotive qualities of Baroque art. His monumental work, The Elevation of the Cross (1610-1611), combines vigorous movement with muscular figures and dramatic diagonals that draw the viewer into the action. The composition contrasts with the calm symmetry of Renaissance art, embodying the Baroque preference for energy and motion (Rowland, 1999).

Baroque architecture further distinguished itself from Renaissance designs through the use of curved forms and elaborate ornamentation. Francesco Borromini’s Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1638-1646) features undulating walls and a dynamic interior, creating a sense of movement even in stillness. These innovations were designed to evoke both grandeur and intimacy, drawing the viewer into a spiritual experience (Boucher, 2018).

Music also played a role in the Baroque era’s multimedia approach to art. The works of composers like Johann Sebastian Bach paralleled the dramatic and ornate qualities of visual art, creating a sensory unity between sight and sound.

Both the Renaissance and Baroque periods revolutionized the Western art tradition, but their goals and approaches were fundamentally different. Renaissance art focused on the rational exploration of perspective, proportion, and classical ideals, while Baroque art emphasized emotional engagement, dramatic contrasts, and movement. Renaissance works like Raphael’s The School of Athens invite intellectual reflection, while Baroque masterpieces like Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa demand emotional immersion.

Together, these movements showcase the evolution of art as a reflection of human experience. The Renaissance celebrates the potential of humanity and reason, while the Baroque reminds us of the power of passion and faith. These artistic legacies remain enduring pillars of cultural history, demonstrating the complexity and diversity of human creativity.

References:

Boucher, Bruce. Italian Baroque Sculpture. Thames & Hudson, 2018.

Baroque Art. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2019.

History.com Staff. Renaissance Art. History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2021.

Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Global History. 15th ed., Cengage Learning, 2017.

Rowland, Ingrid D. The Culture of the High Renaissance: Ancients and Moderns in Sixteenth-Century Rome. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

If you enjoy my work and want to support some amazing causes, you can "Buy Me a Coffee"! All proceeds go toward organizations dedicated to fighting trafficking, supporting survivors, and promoting animal welfare. Your support helps make a real difference. Thank you!

Ive been an early music listener and performer. The patterns of Renaissance and Baroque music are similar to what you describe. My wife and I went to a concert of 3 Bach Advent cantatas this evening. Bach was considered an old fuddy duddy but maybe his genius was combining Renaissance control with Baroque giddiness.