Rococo emerged in early‑ to mid‑18th‑century France as a distinctive artistic language defined by its ornate decoration, lightness, and playful elegance. In direct opposition to the grandeur and formality of Baroque art, the style epitomized by Louis XIV’s absolutism, the Rococo aesthetic embodied the refined leisure and delicate taste of the aristocracy under Louis XV. This style evolved in intimate salon settings, where delicate pastel palettes, sinuous organic curves, and asymmetrical compositions celebrated courtly pleasure and intimacy. During this period, artists such as Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, and Jean‑Honoré Fragonard redefined mythological and pastoral narratives. Watteau’s Pilgrimage to Cythera (1717), for example, merged melancholic longing with playful elegance, establishing a poetic sensibility that would influence later Rococo masters. Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour (1756) exemplified the sumptuous textures, vibrant pastels, and intricate detail that delighted a clientele seeking both charm and sensuality. Fragonard’s The Swing (1767) remains an iconic testament to Rococo’s ability to evoke both whimsical flirtation and refined eroticism (Britannica; Gontar; Smarthistory). Decorative arts and interior design further augmented this style. Lavishly adorned salons such as the Hôtel de Soubise in Paris showcased elaborate stucco work and gilded moldings, while furniture characterized by curved lines and ornate carvings, crafted from materials like mahogany and plush textiles, reinforced the era’s commitment to refined yet playful ornamentation (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Khan Academy).

Despite its celebrated beauty, Rococo soon became embroiled in cultural and political criticism. Intellectual currents of the Enlightenment, emphasizing natural beauty and the importance of individual expression, began to view Rococo’s intricacy and perceived superficiality as emblematic of aristocratic decadence. As Europe edged toward revolution, a growing number of critics and artists denounced the excesses of Rococo, setting the stage for a return to classical austerity. This rejection of Rococo’s decorative opulence ultimately paved the way for Neoclassicism, a movement that emerged in the mid‑18th century as a conscious revival of the ideals, proportions, and disciplined composition of ancient Greece and Rome (Gombrich; Khan Academy).

Neoclassicism did not simply represent a stylistic shift; it was imbued with the intellectual and political ferment of the Enlightenment. Scholars such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whose seminal work Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums argued for the supremacy of Greek art through the ideals of “noble simplicity and calm grandeur,” provided the theoretical underpinnings of this revival. Young aristocrats and artists embarked on the Grand Tour, absorbing the ruins of ancient Greece and Rome and translating these impressions into artworks that strived for order, balance, and moral purpose. Neoclassical artists rejected the light, effervescent brushwork of Rococo in favor of a “crisp” and precise style. In Jacques‑Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784), for instance, the clear, well‑defined contours and rigorously balanced composition underscore themes of duty, sacrifice, and civic virtue. Similarly, David’s The Death of Marat (1793) employs an austere simplicity to cast revolutionary martyrdom in a form that is both direct and morally charged. David’s portraits, such as Portrait of Madame Recamier (1800), further attest to the movement’s dedication to refined personal identity elevated by classical compositional discipline (Smarthistory; The Art Story).

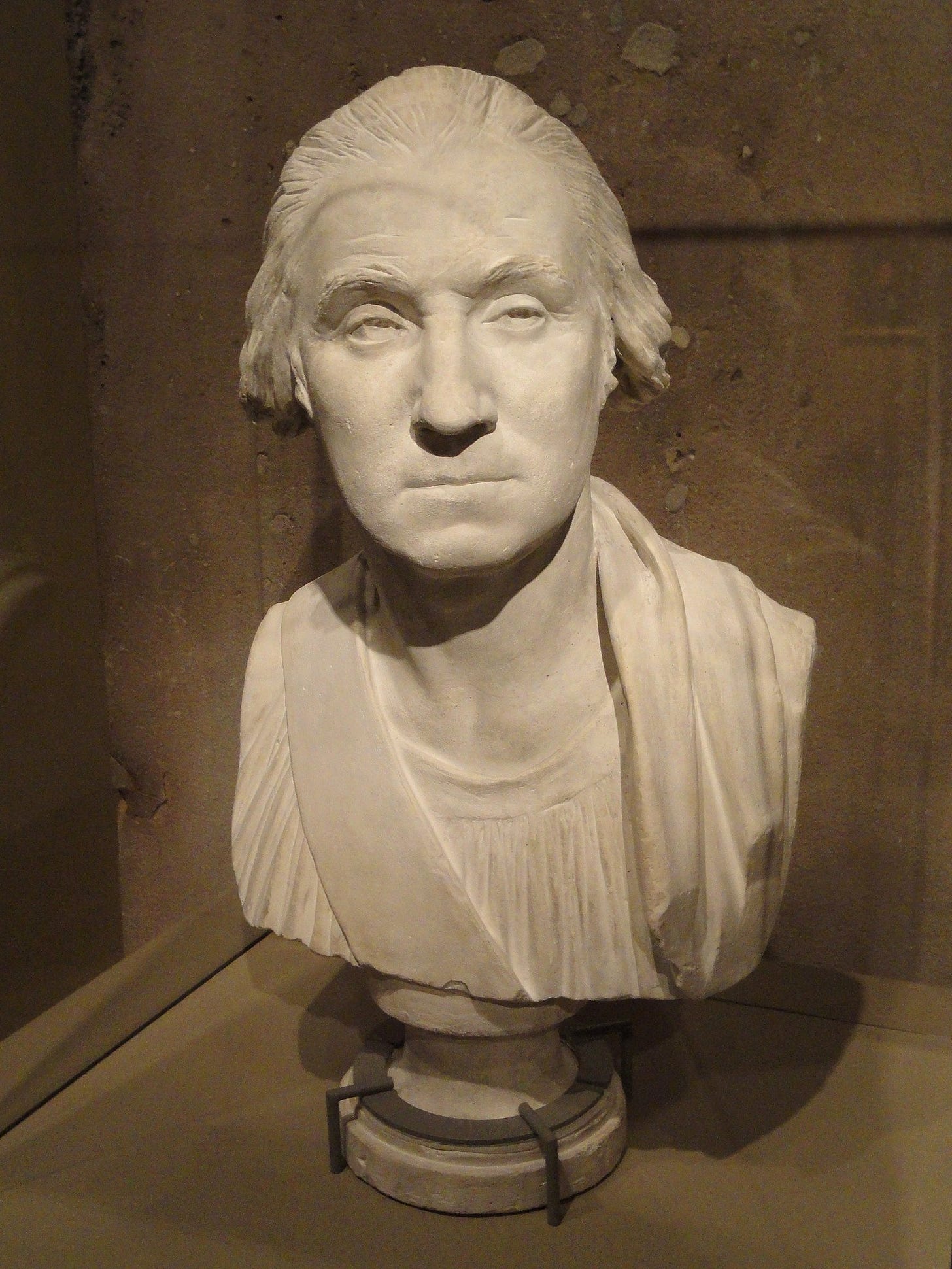

Neoclassical sculpture and architecture further exemplified this return to antiquity. Antonio Canova’s Cupid and Psyche (1794), with its delicate rendering that imparts marble with the appearance of living flesh, epitomizes the idealized anatomical precision and restrained emotion celebrated by Neoclassical sculptors. In parallel, Jean‑Antoine Houdon’s portrait busts, such as his renowned Bust of George Washington (c. 1786), merged meticulous empirical observation with the classical statuary tradition, thereby reinforcing Enlightenment ideals about leadership and virtue (Britannica). Architectural works also reflect these principles: the Panthéon in Paris, originally envisioned as a church and later serving as a mausoleum for national heroes, employs a Greek cross plan, massive Corinthian columns, and a domed roof reminiscent of ancient temples, while Thomas Jefferson’s redesign of Monticello (1772–1809) reveals the international influence of Andrea Palladio’s classical forms on American civic architecture (Gontar; The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Neoclassicism functioned not only as an aesthetic revolution but also as a vehicle for social and political commentary. David’s paintings, imbued with themes of sacrifice and civic responsibility, resonated profoundly at a time when traditional monarchical authority was being challenged by revolutionary ideals. Meanwhile, Houdon’s sculptures provided visual representations of Enlightenment principles by presenting figures such as American Founding Fathers in a dignified, classical manner. This interplay between form, moral content, and political symbolism ensured that Neoclassicism continued to serve as a powerful tool for both cultural critique and state propaganda well into the nineteenth century (Britannica; Smarthistory).

Although Neoclassicism eventually yielded to Romanticism and other emerging movements by the mid‑19th century, its influence endures through the rigorous principles of clarity, symmetry, and moral purpose that continue to underpin academic art and public architecture. The revival of neoclassical ideals during movements such as the American Renaissance and the Beaux-Arts has cemented its role in shaping modern civic monuments, as exemplified by institutions like the Lincoln Memorial. Moreover, the methodological legacy of Winckelmann and the artistic innovations of David, Canova, and Houdon remain cornerstones in art historical scholarship, ensuring that both the decorative exuberance of Rococo and the disciplined austerity of Neoclassicism are recognized as vital chapters in the evolution of European art.

The trajectory from Rococo to Neoclassicism encapsulates a broader shift in 18th‑century European society, from the celebration of aristocratic leisure and ornate beauty to a rigorous, morally driven artistic culture that drew inspiration from the timeless ideals of antiquity. While Rococo remains celebrated for its delightful charm and technical virtuosity, Neoclassicism reasserted a commitment to reason, balance, and civic virtue that resonated with a changing world. Together, these movements illustrate the dynamic interplay between artistic style and the sociopolitical context, a relationship that continues to inform contemporary discourse on cultural heritage and aesthetic values.

References:

Britannica. Rococo. Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., Accessed 30 Jan. 2025. https://www.britannica.com/art/Rococo.

Britannica. Neoclassical Art. Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., Accessed 30 Jan. 2025. https://www.britannica.com/art/Neoclassicism.

Gombrich, E. H. The Story of Art. 16th ed., Phaidon, 1995.

Gontar, Cybele. Rococo. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct. 2003, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/roco/hd_roco.htm.

Khan Academy. Rococo Art. Khan Academy, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-history-basics/beginners-art-history/rococo/a/rococo-art. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

Smarthistory. Rococo: An Overview. Smarthistory, https://smarthistory.org/rococo/. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

Smarthistory. Neoclassicism, an Introduction. Smarthistory, https://smarthistory.org/neoclassicism-an-introduction/. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

The Art Story. Neoclassicism. TheArtStory.org, https://www.theartstory.org/movement/neoclassicism/. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rococo in the Decorative Arts. The Met Collection, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/roco/hd_roco.htm. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

Winckelmann, Johann Joachim. History of Ancient Art. Translated by G. Henry Lodge, F. Ungar Pub. Co., 1849.

Ah, Sister describing the Rococo days of spring in NYC, plus "The Swing" at Contact. ❤️ Great memories!

Great article. Fragonard's The Swing is one of my all-time favorites.