From Cosmic Reaper to Sacred Saint: The Evolution of Lady Death and Santa Muerte in Popular Culture

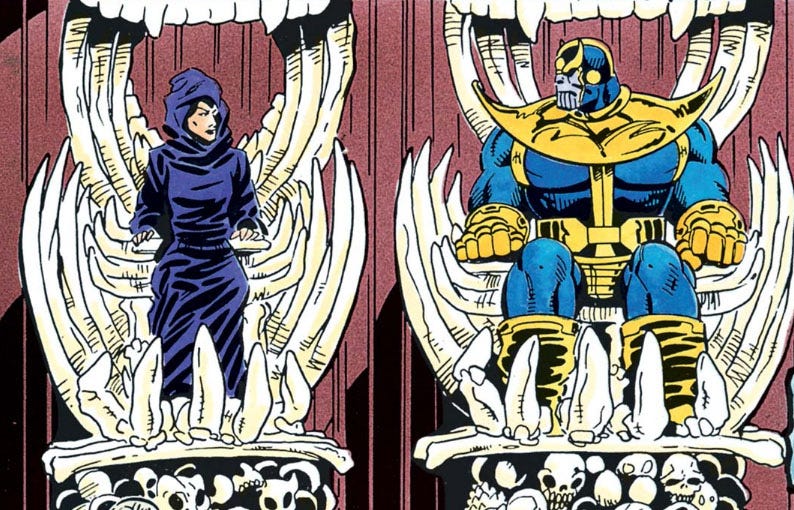

Marvel Comics’ depiction of Death as a cosmic, feminine force represents one of the publisher’s most enigmatic mythologies. Commonly known as “Lady Death” or “Mistress Death,” this entity not only catalyzes major narrative arcs, most famously influencing Thanos’ quest for the Infinity Gauntlet, but also symbolizes the inexorable nature of mortality and the delicate balance between life and death.

Marvel’s abstract cosmic entities have long served as narrative instruments that imbue its vast universe with mythic gravitas. Among these, Death occupies a singular position. Although officially known as “Death,” popular discourse sometimes refers to her as “Lady Death” or “Mistress Death” to emphasize her feminine presentation. Her dynamic role, especially as the object of Thanos’ unrequited obsession, illustrates how Marvel uses cosmic abstraction to explore themes of mortality, desire, and universal balance (Cunningham 187–205; “Death (Marvel Comics)”). Moreover, the cultural phenomenon of Santa Muerte in Mexico, as explored by Dr. Andrew Chesnut, provides an intriguing point of comparison. Both figures, though arising in radically different cultural milieus, serve as powerful personifications of death, offering both awe and solace.

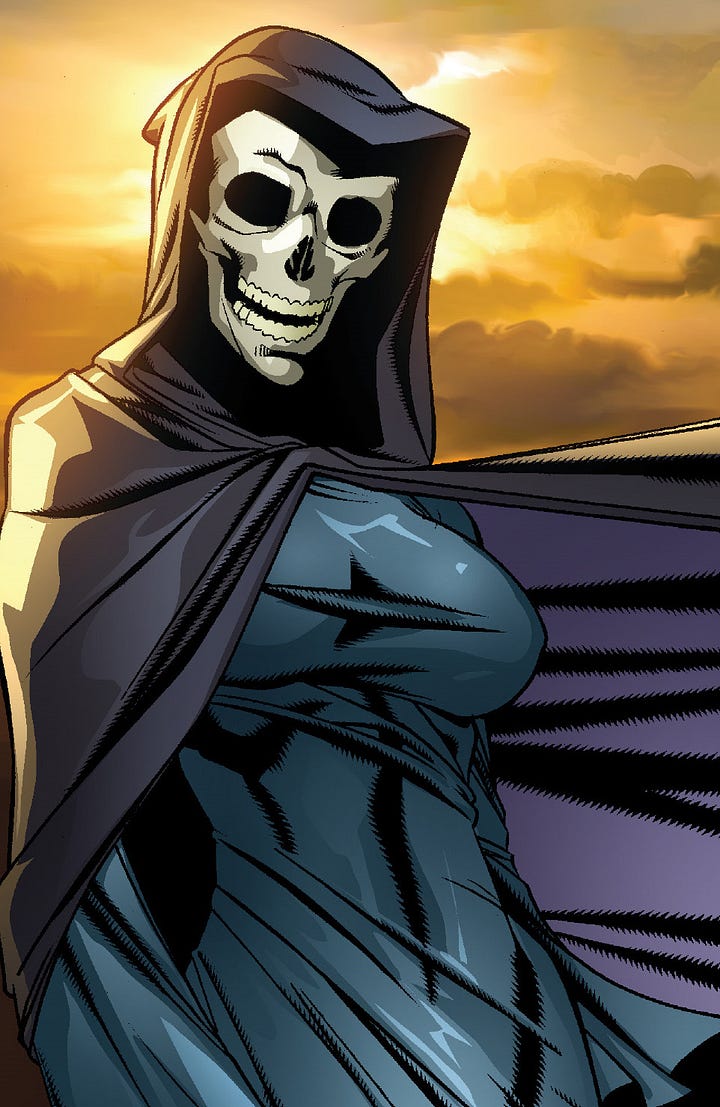

Marvel’s Death first emerged in the early 1970s as a narrative tool in cosmic stories. Her debut in Captain Marvel #26 (June 1973), created by Mike Friedrich and Jim Starlin, introduced a character based on the timeless personification of death. Initially depicted as a vague, abstract force, Death gradually evolved into a distinct, feminine figure with a skeletal visage and a flowing, dark cloak; a design that underscores both inevitability and seductive mystery (Tom DeFalco et al., The Marvel Encyclopedia 2019). Over subsequent decades, various artists refined her appearance, making her one of Marvel’s most visually striking cosmic entities. This evolution mirrors Marvel’s broader trend of transforming abstract forces into characters with personality, agency, and narrative significance (Cunningham 187–205).

In Marvel’s mythos, Death is far more than an abstract force. She is portrayed as an omnipresent arbiter of mortality who interacts intimately with the living, most notably through her relationship with Thanos. Thanos’ obsessive love for Death drives the narrative of The Infinity Gauntlet and other storylines, wherein he seeks to prove his devotion by committing acts of universal destruction (Smith 456–478). Beyond Thanos, Death appears in various cosmic sagas as a force that brings balance to the universe by reclaiming life, underscoring the paradox that death is both feared and fetishized. Her interventions often raise philosophical questions about fate, free will, and the nature of existence, thereby positioning her as a complex character whose motivations and actions are open to scholarly interpretation (Anderson 214–232).

The evolution of Death’s visual portrayal is notable for its blend of classical iconography and modern graphic design. Early depictions were sparse and symbolic, but later renderings emphasize her skeletal form, often shown cloaked in dark robes with subtle, ethereal luminescence. This visual motif borrows from the European Grim Reaper and merges it with Art Deco influences, sharp lines, metallic hues, and geometric patterns, to create an image that is both timeless and contemporary (Wright 45–63). The transformation of Death’s appearance into that of a striking female figure speaks to Marvel’s intention to humanize even the most abstract forces, making them accessible to readers while retaining their cosmic, almost unknowable essence. This artistic choice allows Death to operate as a narrative catalyst while also serving as a symbol of universal inevitability.

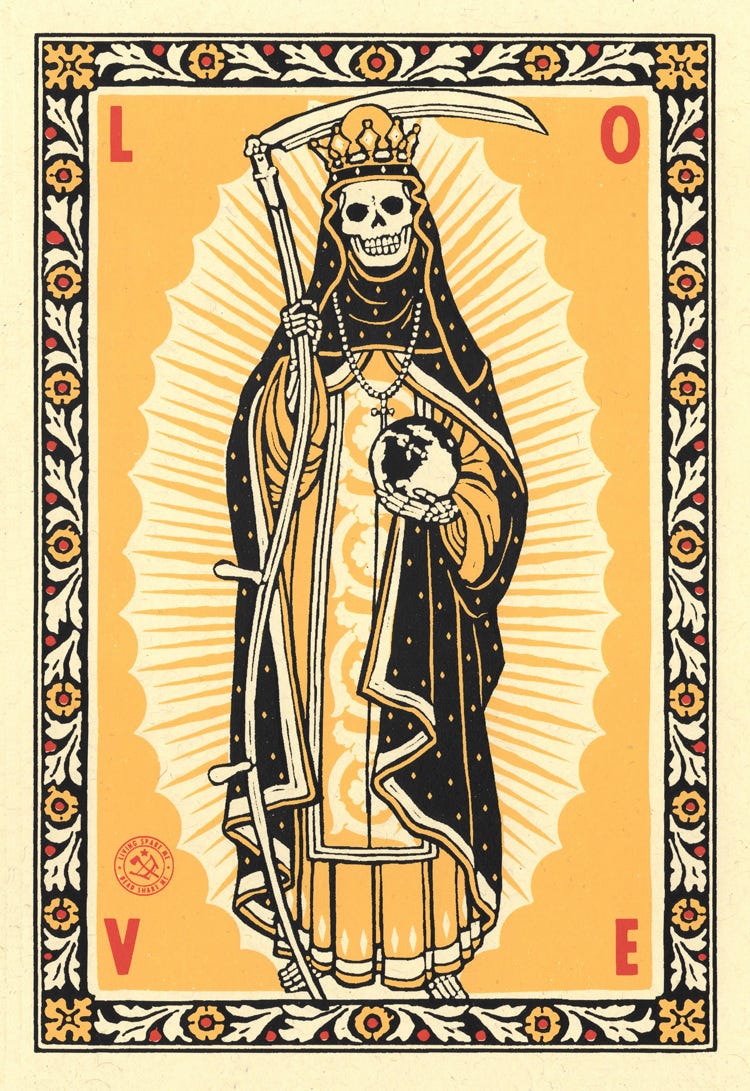

Death’s role in Marvel Comics operates on multiple thematic levels. On one hand, she represents the inevitability of death; a universal constant that transcends individual heroism or villainy. On the other hand, her seductive and sometimes capricious portrayal complicates traditional notions of mortality, suggesting that death can be as alluring as it is fearsome (Jones 102–115). This duality is central to understanding the character’s cultural impact: Marvel’s Death challenges the audience to confront their own mortality, while also offering a form of cosmic balance that is both comforting and unsettling. In a broader cultural context, similar personifications of death, such as Santa Muerte in Mexico, reflect a human need to render the abstract tangible, thus providing solace amid life’s uncertainties (Mackrell 78–89; Chesnut 26–50).

Santa Muerte, or “Our Lady of Holy Death,” is a folk saint who has emerged as a potent figure in Mexican religious practice. Despite condemnation by the Catholic Church, she is revered by millions for her protective and healing qualities. Like Marvel’s Death, Santa Muerte is typically depicted as a skeletal figure draped in robes, though her iconography varies by context (Santa Muerte, Wikipedia). Dr. Andrew Chesnut’s seminal work, Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint (Oxford University Press, 2012), provides a comprehensive analysis of how Santa Muerte embodies both the terror and comfort associated with death. Chesnut argues that, in a society plagued by violence, poverty, and social marginalization, Santa Muerte serves as both a guardian and a liberator; offering miracles related to health, wealth, and protection (Chesnut 26–50). This role is analogous to Marvel’s Death, who, through her cosmic interventions, underscores the inescapable nature of mortality while simultaneously inspiring acts of defiance and desire. Both figures illustrate the human impulse to personify the end of life, imbuing it with both awe and agency.

Dr. Andrew Chesnut is one of the foremost scholars on Santa Muerte, and his research has shed light on the rapid expansion and transformative impact of this folk saint’s cult. In his interviews and writings, Chesnut describes Santa Muerte as “the fastest-growing new religious movement in the Americas,” noting that her appeal lies in her ability to provide tangible hope in times of crisis (Chesnut; Rollin). Chesnut’s work emphasizes that Santa Muerte is not simply a harbinger of doom but a multifaceted figure who performs miracles for her devotees; ranging from healing and protection to financial prosperity. His research also explores the syncretic origins of Santa Muerte, tracing her lineage back to pre-Columbian death deities and the Spanish Grim Reaper. By comparing these origins to her modern manifestations, Chesnut illustrates how Santa Muerte’s symbolism has been adapted to meet the needs of a diverse and often disenfranchised populace. This comparative framework offers valuable insights into the universal human desire to confront and master the concept of death (Chesnut 26–50; Rollin).

Despite the shifting tastes of comic book audiences and religious adherents alike, Marvel’s Death remains a potent symbol within the cosmic hierarchy. Her presence in major storylines and her influence on characters like Thanos have cemented her status as an essential element of Marvel’s mythos. Similarly, Santa Muerte continues to grow in popularity, particularly among marginalized groups who find solace in her protective and healing powers. The convergence of these two personifications of death, one fictional and cosmic, the other deeply rooted in cultural tradition, highlights a universal phenomenon: the need to externalize and negotiate the inescapable reality of mortality. As Marvel adapts its cosmic narratives for the screen and as Santa Muerte’s cult expands in the Americas and beyond, both figures underscore the enduring human fascination with death as both an end and a transformative force (Cunningham; Chesnut; Anderson).

Marvel’s depiction of Death, as a character known variously as Lady Death, Mistress Death, or simply Death, demonstrates the power of comic book mythology to transform an abstract concept into a narrative force with complex emotional and philosophical dimensions. By blending classical imagery with modern storytelling, Marvel has created a figure that not only drives cosmic narratives but also invites readers to confront the paradox of mortality. The cultural parallel provided by Santa Muerte, as detailed in the works of Dr. Andrew Chesnut, reinforces the idea that personifications of death serve a critical role in both fiction and reality. Together, these two figures illustrate how death, whether as a cosmic entity or a folk saint, continues to captivate and inspire, offering both solace and a reminder of the fragile balance between life and death.

References:

Anderson, Mark. The Personification of Death in Popular Culture. Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 53, no. 2, 2020, pp. 214–232.

Chesnut, R. Andrew. Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Chesnut, R. Andrew. Santa Muerte: The Fastest-Growing New Religious Movement in the Americas. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Cunningham, Brian. Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. HarperCollins, 2012.

Jones, Mary. The Personification of Death in Modern Mythology. Mythological Studies Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 102–115.

Mackrell, Judith. Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation. Pan Books, 2013.

Rollin, Tracey. Santa Muerte: The History, Rituals, and Magic of Our Lady of the Holy Death. Weiser Books, 2017.

Smith, John. Cosmic Entities in Marvel Comics: A Thematic Analysis. Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 48, no. 3, 2015, pp. 456–478.

Tom DeFalco, Peter Sanderson, Tom Brevoort, Michael Teitelbaum, Daniel Wallace. The Marvel Encyclopedia: The Definitive Guide to the Characters of the Marvel Universe. DK Publishing, 2019.

Wright, Bradford. The Mythology of Marvel’s Cosmic Hierarchy. Marvel Studies Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, pp. 45–63.

Interesting piece! I would never have known, not being a comic person.

So here I am learning as I go on and the shock of death with breasts image hit me in a way unexpected. I have a real push back on it—a horrific thought for the milk of life to be adorning the body of death?

Was there anything about that in any of the research?