Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) revolutionized modern art through his radical distillation of form and color, pioneering Neo-Plasticism and laying a foundation for generations of artists, architects, and designers. His career evolved from Hague School; inflected naturalism to crystalline abstraction, and eventually to the dynamic grid compositions of wartime New York. This transformation unfolded alongside his theoretical writings, collaborative movements, and transnational influence across modern design and abstraction.

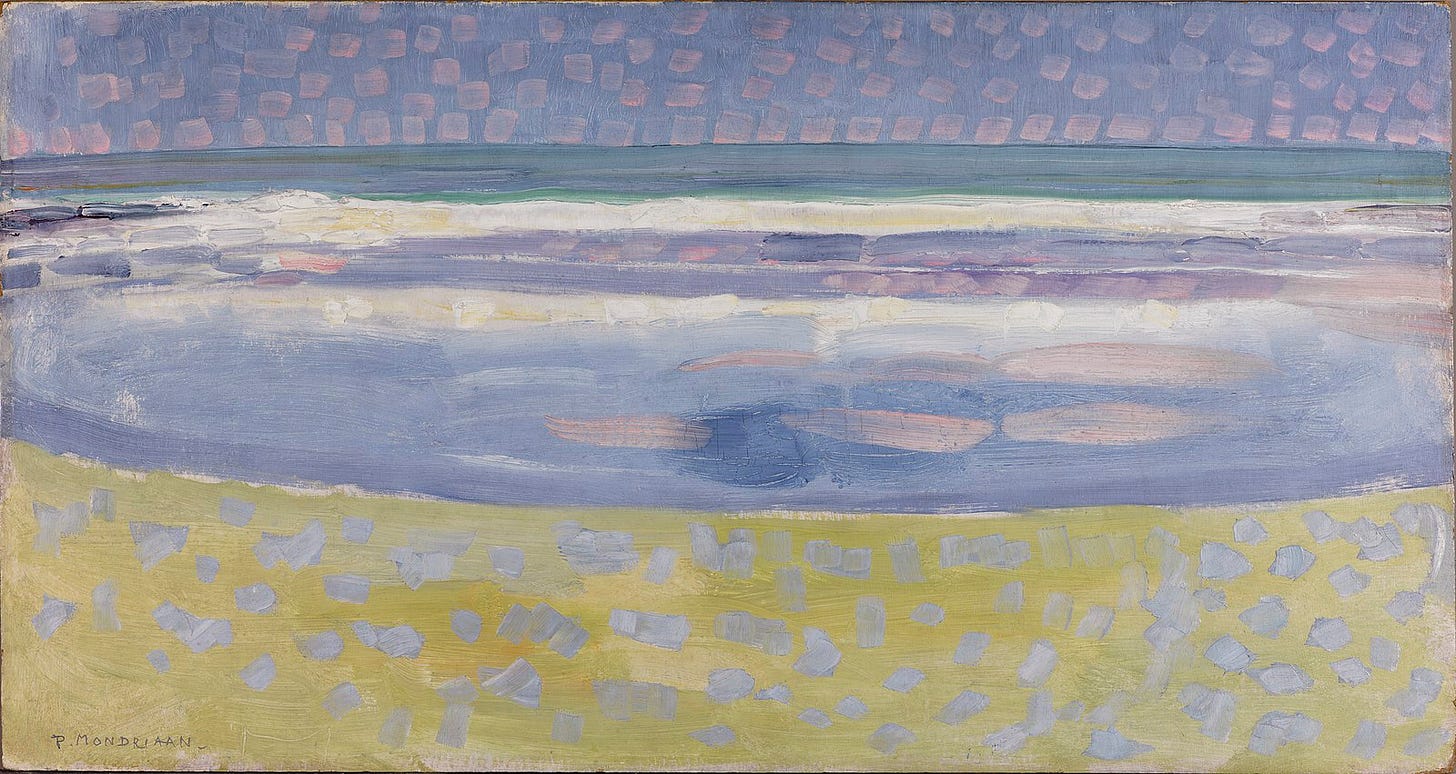

Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan was born on March 7, 1872, in Amersfoort, Netherlands, into a family of educators; his father a drawing teacher and his uncle, Frits Mondriaan, a student of Hague School master Willem Maris (Britannica; MoMA). Encouraged early, Mondrian studied at the Amsterdam Rijksakademie from 1892 to 1897, honing his plein-air skills under the guidance of Cornelis Springer and Anton Mauve. His early work reveals traditional realism interlaced with subtle innovations in rhythm and composition, as seen in Geese Flying over a Meadow (c.1891) and Beach at Scheveningen (1909) (Joosten 12–15; piet-mondrian.eu). A major early breakthrough came with Evening; Red Tree (1908), which married expressive impasto and an underlying structural rhythm, marking a transition toward abstraction (MoMA).

Paintings from this era such as Reformed Church at Winterswijk (1898) and Trees along the Gein (1905) illustrate his command of line and atmosphere. Later works like Oostzijdse Mill in the Evening (1907–08) and Mill in Sunlight (1908) began flattening natural forms into more abstract, rhythmic structures, a process intensified in pieces like Dune I (1909) and Sea after Sunset (1909), where saturated colors and impasto were deployed to express mood and composition more than representational fidelity (Kunstmuseum Den Haag).

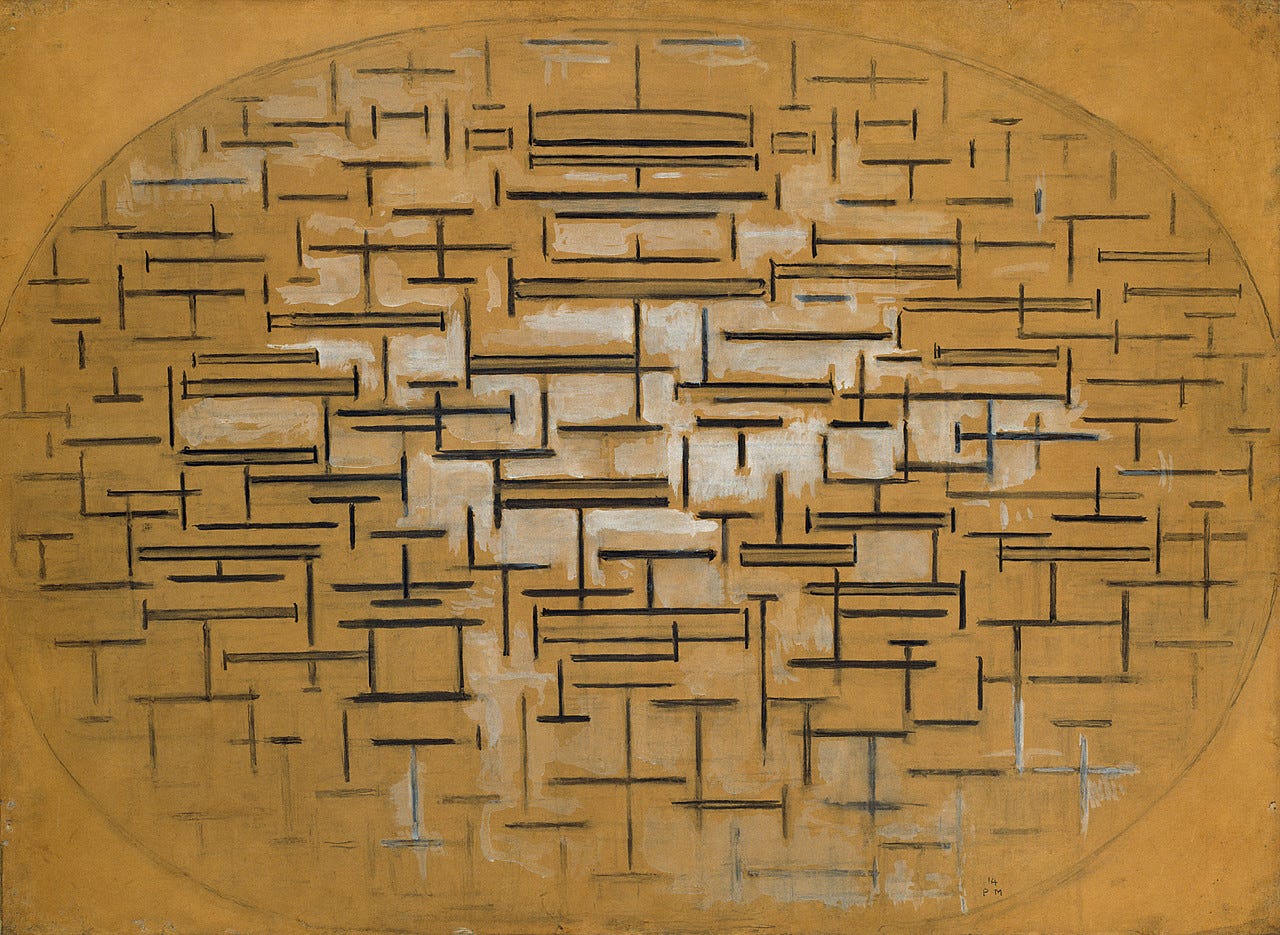

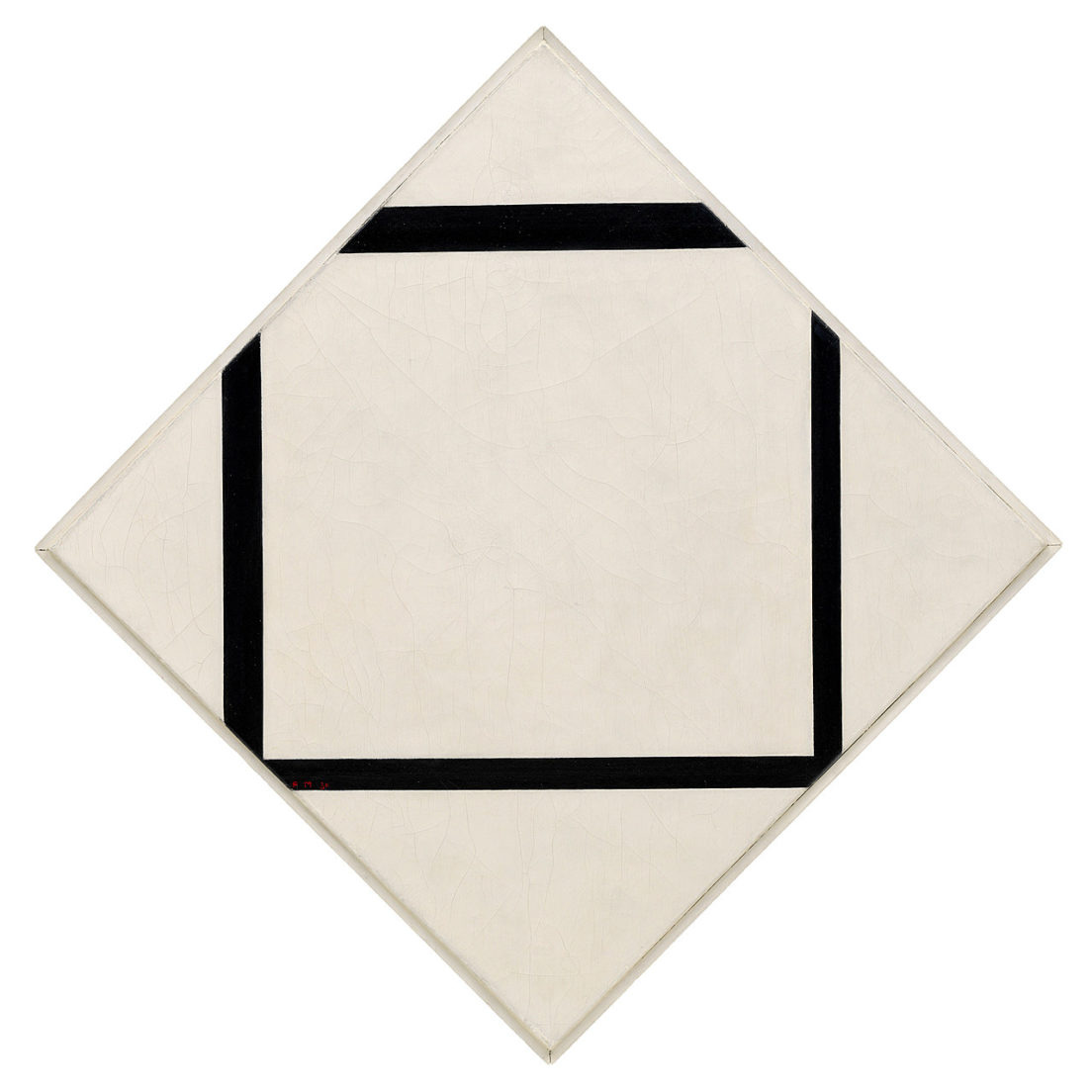

In 1911, Mondrian relocated to Paris and dropped the “a” from his surname, asserting a new avant-garde identity (The Art Story). Immersed in the circles of Picasso, Braque, and Gris, he embraced Cubist techniques. In The Sea (Ocean 5)(1912) and Tableau I: Lozenge with Four Lines (1914), he fragmented form and began experimenting with the spatial potential of grids and rotated canvases (Guggenheim). His growing belief in art as a spiritual discipline was shaped by Theosophy, particularly the writings of Helena Blavatsky and Annie Besant.

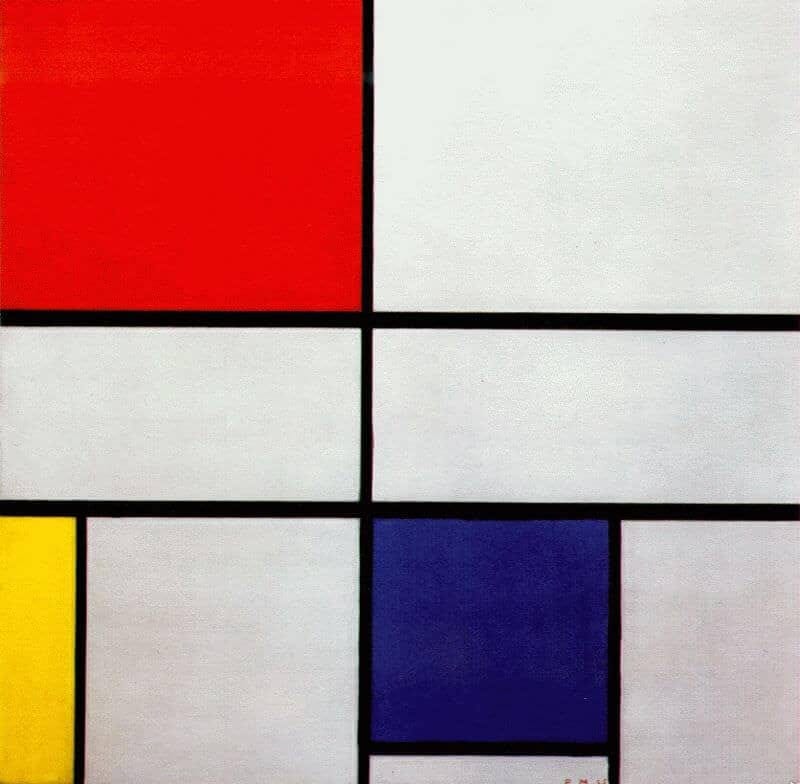

During this time, Mondrian formulated and published his Neo-Plasticist theory. His essays “De Nieuwe Beelding in de schilderkunst” and “Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art” (1917–18) for De Stijl emphasized pure abstraction through vertical and horizontal lines and primary colors as a path toward universal harmony (Joosten 45–60; piet-mondrian.eu). His Composition in Brown and Gray (1913) and Composition in Oval with Color Planes I (1914) signaled a decisive turn toward non-objective art (MoMA).

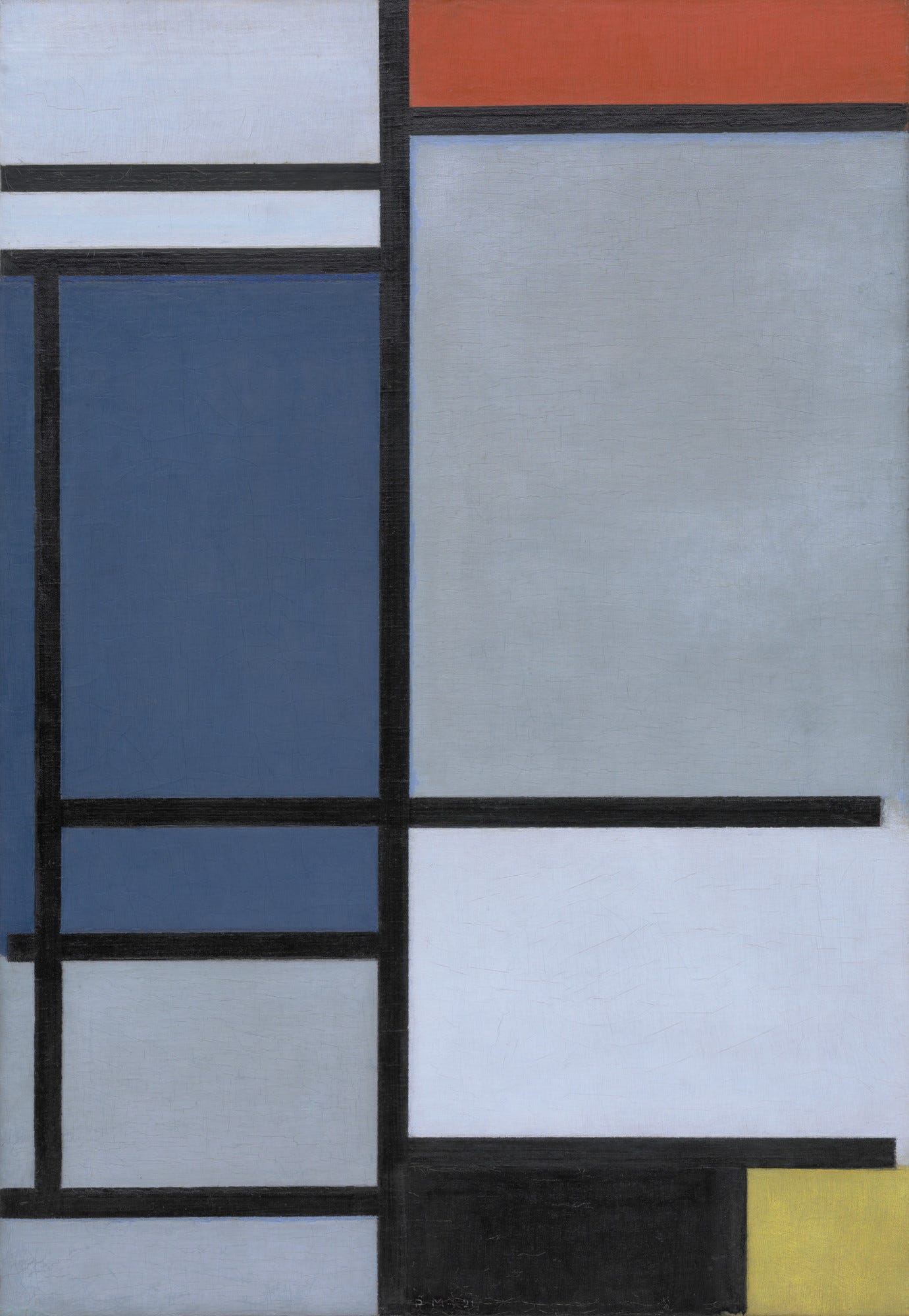

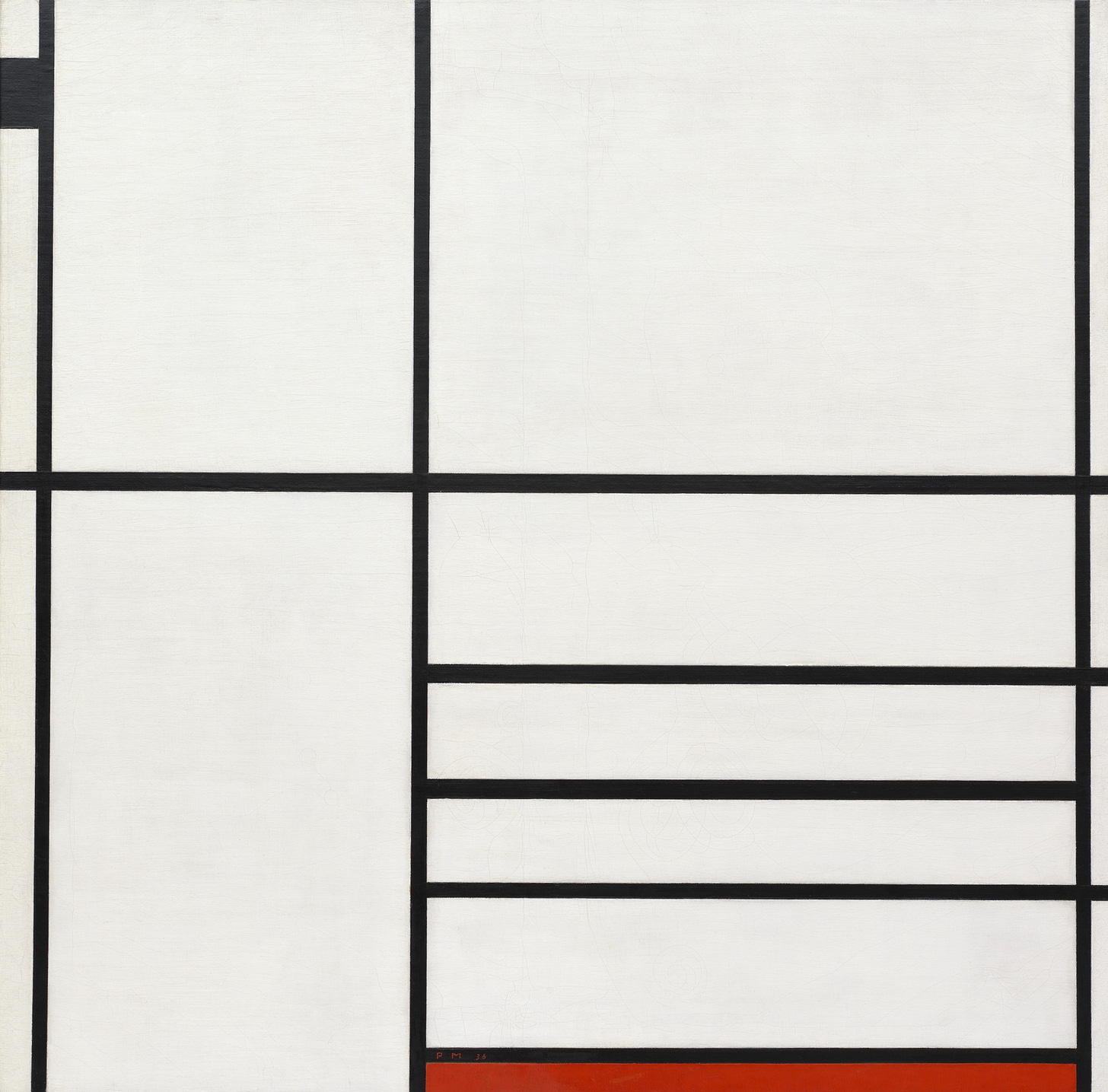

Returning to the Netherlands during World War I, Mondrian co-founded De Stijl with Theo van Doesburg in 1918. His canvases from the early 1920s, Composition C (1920), Composition with Red, Blue, Black, Yellow, and Gray (1921), and Composition in White, Black, and Red (1936), reflect a progressive elimination of representational elements and a refined application of Neo-Plastic principles (MoMA). He achieved visual harmony through asymmetry and the use of line weight to create a sense of “dynamic equilibrium,” a concept elaborated in his 1923 essay “Neo-Plasticism in Painting.”

Mondrian's ideas extended into architecture through collaborations with Gerrit Rietveld, such as the iconic Schröder House in Utrecht (1930), which embodied De Stijl’s rectilinear aesthetics and deeply influenced the International Style (Joosten 112–18; piet-mondrian.eu).

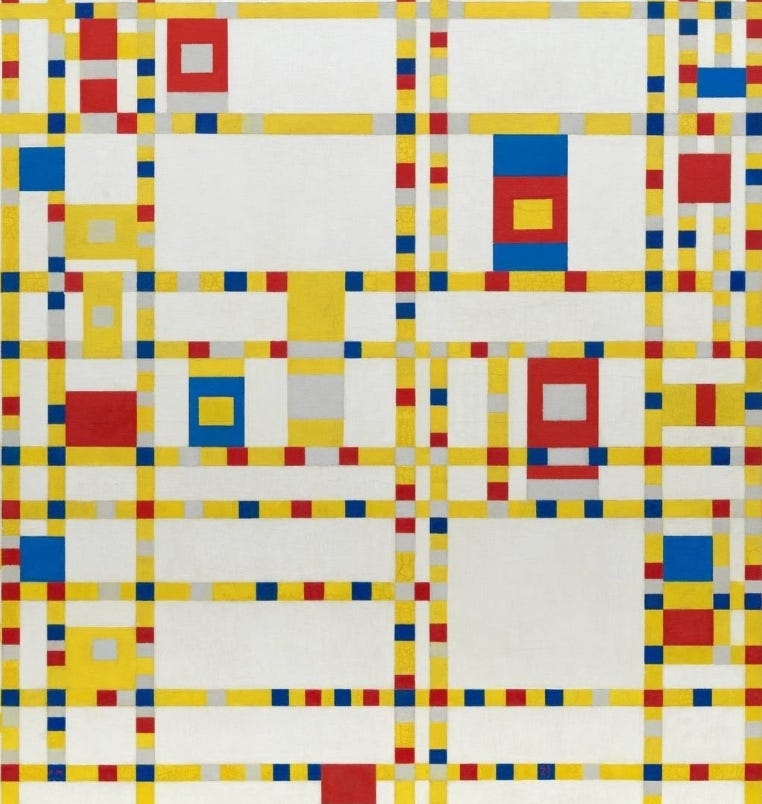

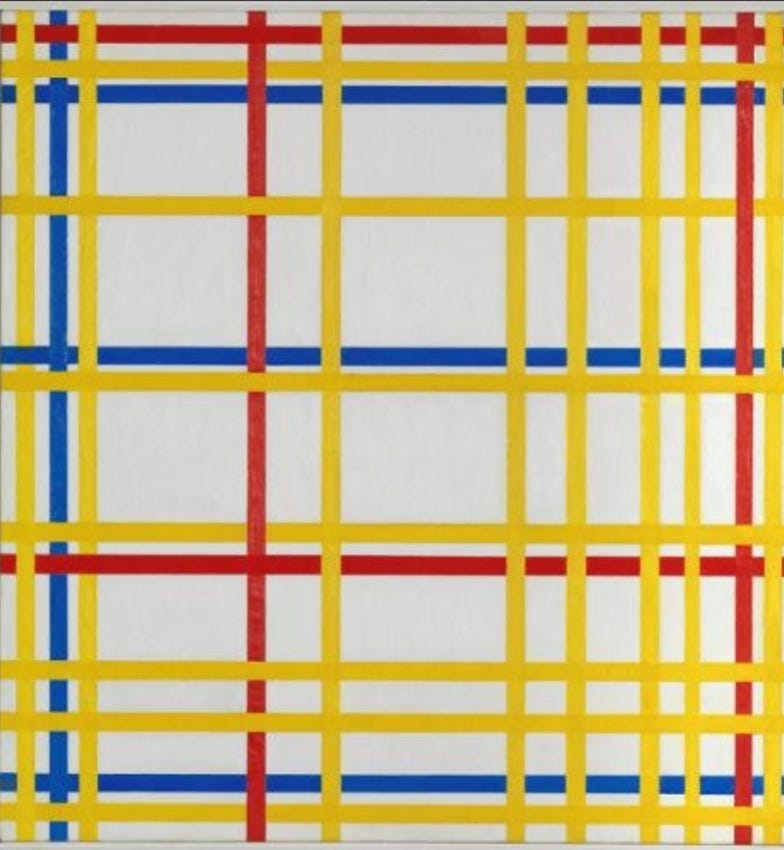

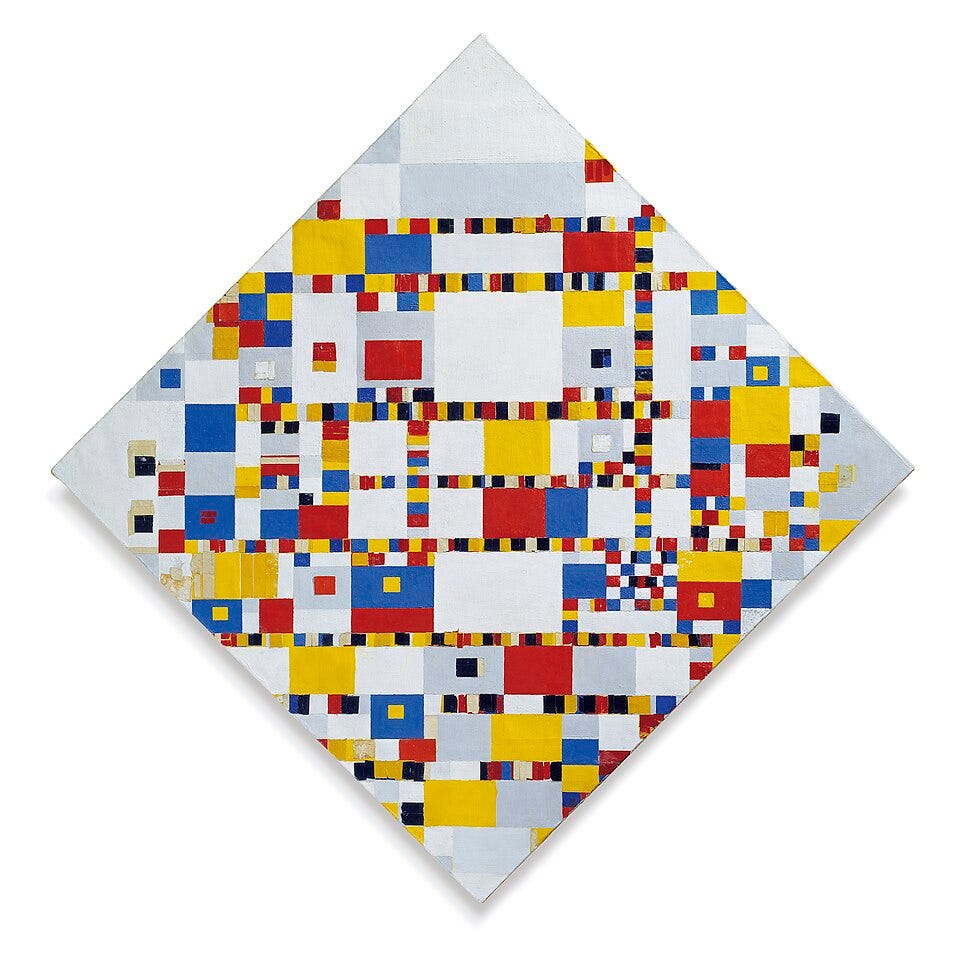

With the rise of fascism, Mondrian fled to London in 1938 and then to New York in 1940. His New York period saw a vibrant reimagining of his formal vocabulary. Works such as Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942–43) translated Manhattan’s jazz rhythms into pulsing grids of yellow, red, and blue squares (MoMA). His New York City series, New York City I (unfinished, Kunstsammlung Düsseldorf), New York City (1942, Centre Pompidou), and his final work, Victory Boogie Woogie (1944), demonstrate a radical intensification of fragmentation, rhythm, and chromatic interplay (Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza; Centre Pompidou; Wikipedia).

New York City I, featuring removable paper strips, exemplifies Mondrian’s desire to keep composition in flux. Victory Boogie Woogie, is widely interpreted as his ultimate expression of dynamic equilibrium and an homage to both abstraction and American urban energy.

Mondrian’s writings established him as a preeminent art theorist. He saw art as “a concrete expression of vitality,” requiring “the annihilation of static equilibrium” to realize dynamic balance (MoMA). His Neo-Plastic Principle paralleled and influenced other abstract movements like Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism and the Bauhaus curriculum. His cross-disciplinary influence ranged from Rietveld’s furniture design to modernist pedagogy and urban planning (Joosten xxiv–xxvi; piet-mondrian.eu).

Piet Mondrian died of pneumonia on February 1, 1944, in New York City. He was buried at Cypress Hills Cemetery, Queens, a site revisited by MoMA curators in 2019 as a gesture of homage (The New Yorker). His legacy is preserved by the Mondrian/Holtzman Trust, which organizes exhibitions and oversees his estate. MoMA’s 2020 retrospective, Piet Mondrian: 1872–1944, situated his work within a global context of abstraction (MoMA).

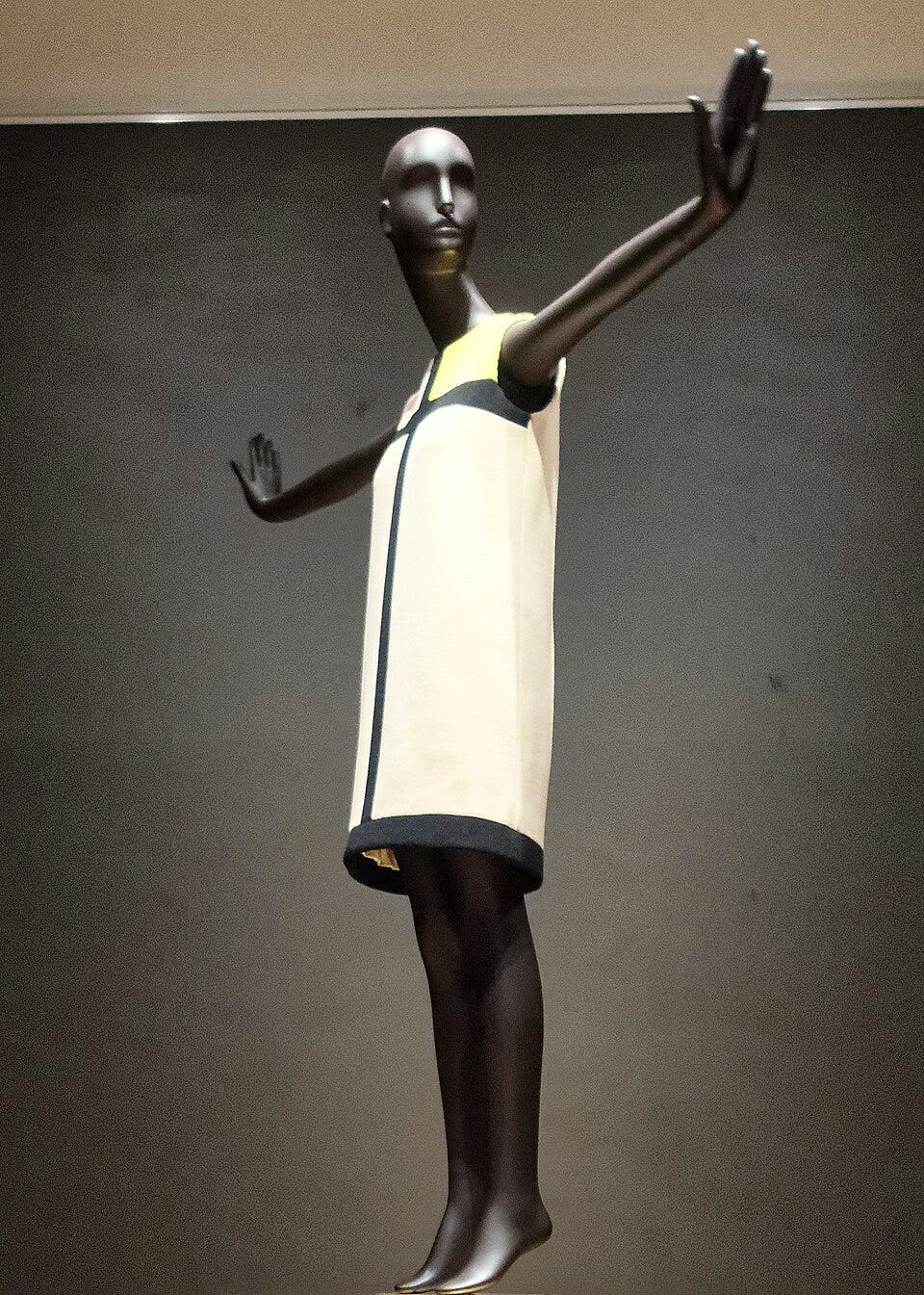

Mondrian’s visual language continues to permeate contemporary design and culture. From Yves Saint Laurent’s Mondrian dresses (1965) to the New York City subway map, his grid aesthetic remains iconic (The Art Story). Today, artists and theorists alike explore the philosophical and visual implications of his Neo-Plasticist approach, affirming his role as a touchstone of twentieth-century modernism.

References:

Blotkamp, Carel. Piet Mondrian: The Art of Destruction. Yale UP, 1994.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopedia. Piet Mondrian | Biography, Paintings, Style, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica, Accessed 14 Feb. 2025.

Composition in Red, Blue, and Yellow. MoMA, object no. 80160.

Composition in White, Black, and Red. MoMA, object no. 2.1937.

Composition with Red, Blue, Black, Yellow, and Gray. MoMA, object no. 154.1957.

Evening; Red Tree. MoMA.

Joosten, Joop M., ed. Mondrian Essential Writings. Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Piet Mondrian: 1872–1944. MoMA Exhibition, 2020.

Piet Mondrian. Centre Pompidou, New York City (1942).

Piet Mondrian. Guggenheim Museum, accession no. 3052.

Piet Mondrian. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, New York City I (unfinished).

Piet Mondrian Paintings, Bio, Ideas. The Art Story, Accessed 14 Feb. 2025.

The True Grid. The New Yorker, 9 Oct. 1995.

A Visit to Mondrian’s Grave. The New Yorker, 4 Mar. 2019.

Wikipedia contributors. Victory Boogie Woogie. Wikipedia, 2025. piet-mondrian.eu. Accessed 14 Feb. 2025.

Fantastic read once again. 🖤

One of my favorite all-time artists. When people knock modern art, I refer them to Mondrian's early work. He was a fascinating artist and thinker. Lovely post as always!!