Al-Andalus, the lands of Islamic Iberia from 711 to 1492, produced some of the most celebrated architectural masterpieces of the medieval world. Two iconic monuments stand out for their scale, beauty, and innovative design: the Great Mosque of Córdoba (established in the 8th century) and the Alhambra palace-fortress of Granada (13th–14th centuries). Each exemplifies the ingenuity of Moorish architects and artisans, showcasing new forms and techniques that would influence Islamic art in the West for centuries. These buildings are not only engineering feats but also visual symphonies of light, geometry, water, and calligraphy, all employed within a distinctive architectural vocabulary.

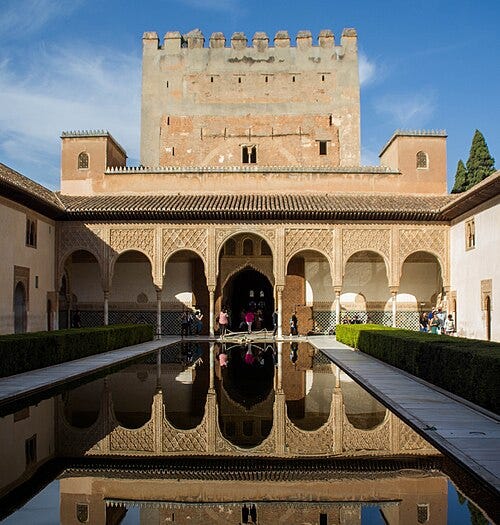

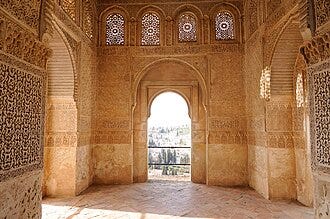

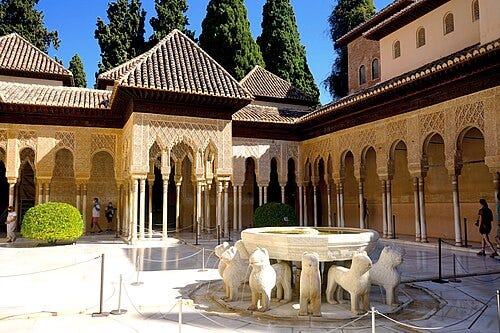

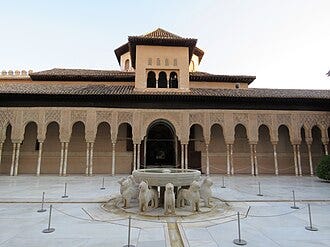

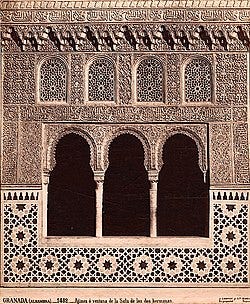

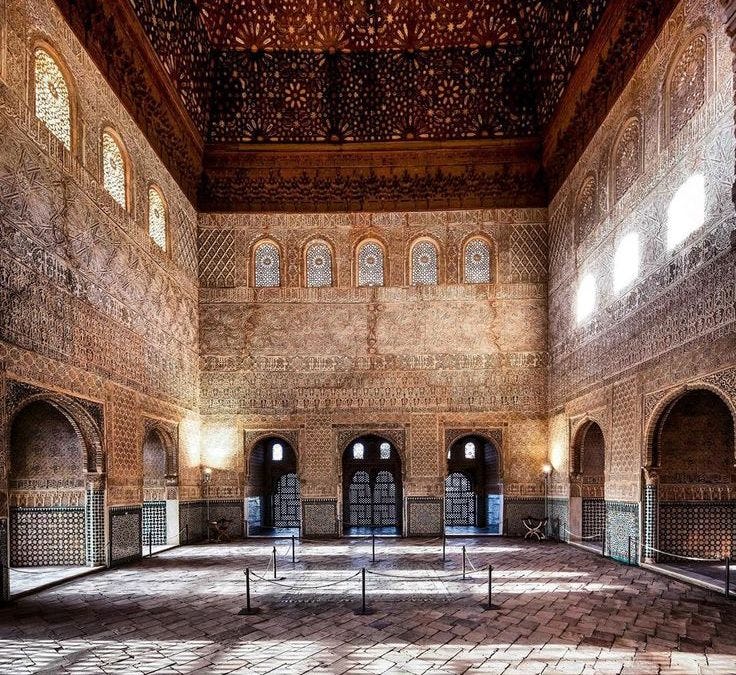

Perched atop the hills of Granada, the Alhambra (from Arabic Qal‘at al-Ḥamrāʼ, “the red fort”) is a sprawling palace-city that served as the seat of the Nasrid dynasty. Its design centers on a series of rectangular courtyards and interconnected halls, creating an intimate yet ethereal environment noted for carefully proportioned open spaces and vistas. Each palace courtyard (such as the Court of the Myrtles and the Court of the Lions) is ringed by arcaded porticoes and chambers, an inward-facing layout that blurs the boundary between indoors and outdoors. This arrangement not only provided privacy and cooling ventilation, but also framed the architecture to be experienced from within, with myriad viewpoints and reflections orchestrated for the viewer. The result is a “kaleidoscopic collection” of spaces where one’s gaze is constantly drawn through horseshoe arches and latticed windows to gardens, pools, and distant landscapes.

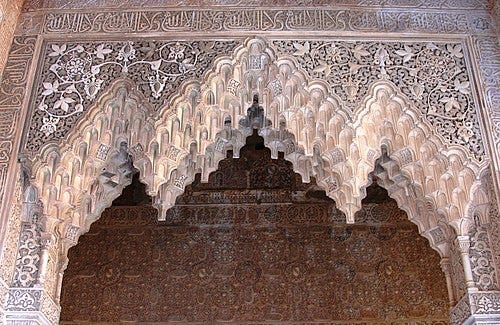

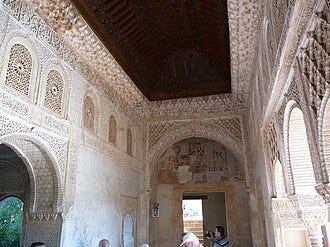

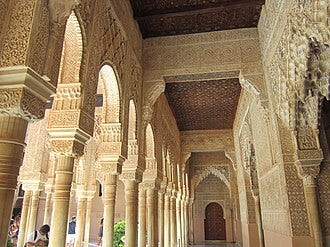

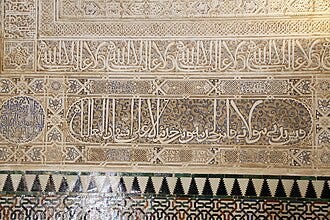

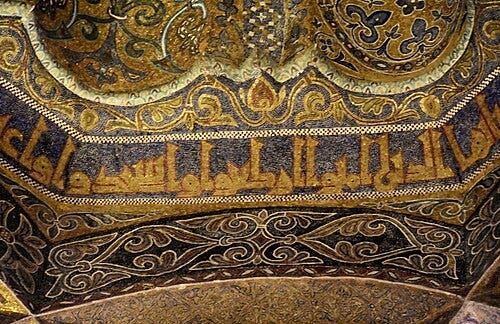

One of the Alhambra’s most striking qualities is the extraordinary richness of its surface decoration. The upper walls of its palaces are covered in intricately carved stucco that is so fine and perforated it has been likened to stone “lace”. This yesería (stucco work) displays a mesmerizing combination of geometric strapwork, scrolling vegetal arabesques, and cursive Quranic inscriptions, all seamlessly interwoven into repeating patterns. The Nasrid artisans achieved a level of detail and delicacy in plaster that seems to dematerialize the walls; by carving deep into the stucco and undercutting forms, they created shadows and depth that produce a filigree effect, especially when sunlight rakes across the surfaces. Travelers and historians have long marveled at this “lace-like” filigree of the Alhambra’s ornament, cut from a mixture of plaster and marble dust and often set with colored pigments. Originally, these stucco patterns were polychrome, painted in vibrant blues, reds, greens, and gilded accents, though centuries of weathering have left most surfaces a monochromatic off-white. Nonetheless, even in their subdued state, the carved inscriptions and vegetal scrolls retain a quiet elegance, epitomizing the Islamic ideal of transforming humble materials into manifests of paradise through artistic skill.

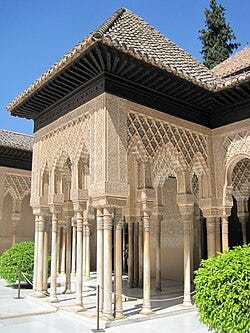

The Alhambra’s decoration is not merely applied ornament but is integral to its architectural expression. Historians note that interest in the Nasrid palace interiors is created “not by the application of a skin of decoration to a separately conceived building but by the transformation of the [architectural] components themselves”. In other words, the columns, arches, and vaults are designed in concert with their decoration to achieve a unified aesthetic and spatial experience. The palace’s slender marble columns (often arranged in pairs or trios) support multilobed or muqarnas-adorned arches that seem to billow like fabric, contributing to the sense of lightness and luxury. Many of these columns were quarried from local Macael marble, and though structurally modest, they are enhanced by ornate capitals carved with acanthus leaves and Nasrid mottoes. The combination of thin columns and perforated stucco screens gives Nasrid architecture its famously insubstantial, dreamy quality, described by some as evoking an “intimate paradise” on earth. This stylistic approach was practical as well; walls of brick and rammed earth were coated in plaster and ornament, a lightweight construction that insulated interiors and could be rapidly decorated. The Alhambra thus exemplifies an architecture of surface and atmosphere, a theater of refined ornamentation, where structure is masked by artistry.

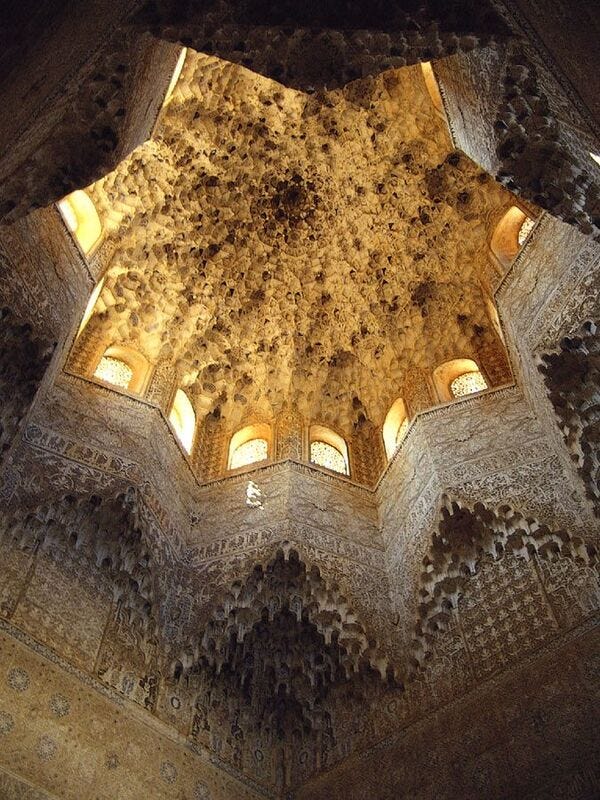

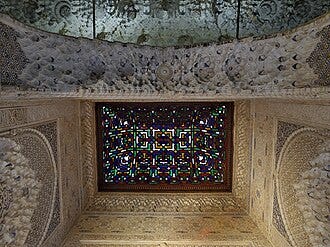

Among the Alhambra’s most celebrated formal innovations is its use of muqarnas vaulting. Muqarnas (called mocárabes in Spanish) are three-dimensional decorative forms composed of niche-like cells, often compared to stalactites or honeycombs. In the Alhambra, the Nasrid architects employed muqarnas to breathtaking effect in several vaulted chambers, most famously the Hall of the Two Sisters (Sala de las Dos Hermanas) and the Hall of the Abencerrajes. These 14th-century halls are crowned with lofty domes of muqarnas that seem to drip from above, their myriad plaster prisms catching and fracturing the light. The honeycomb vault of the Hall of the Two Sisters, for example, contains over 5,000 individual plaster cells arranged in tiers that form star patterns when seen from below. This creates a dynamic play of light and shadow as daylight enters through high windows, illuminating different facets of the muqarnas throughout the day. The visual effect is deliberately otherworldly; as one contemporary writer described, “the [muqarnas] vaulting [creates] a mesmerizing play of light and shadow”, suggestive of a cosmic firmament or the heavens themselves. In symbolic terms, such vaults might reference the Islamic vision of the heavenly dome or the infinite complexity of creation. Technically, they also represent a sophisticated response to transitioning from a square room to a lofty dome: the muqarnas cells gradually project inward to form a circular or star-shaped apex, an approach that is both structural and decorative. The Nasrids were not the first to use muqarnas, but their immense variety of shapes and precise mathematical proportion made the Alhambra’s muqarnas domes unique in the western Islamic world. These forms were crafted in plaster using molds, then assembled in place; an efficient method that produced a dazzling, weightless appearance.

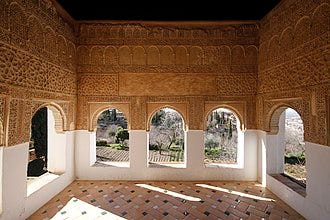

Equally innovative was the Alhambra’s integration of gardens and pavilions into the royal residential complex. This reflects the broader garden-pavilion concept in Islamic palace architecture, wherein architecture and landscape are blended to create a vision of paradise on earth. The Nasrid sultans built the Generalife (Jannat al-‘Arīf, “Garden of the Architect”) as a summer palace and agricultural estate just uphill from the main Alhambra palaces. The Generalife’s design epitomizes the concept of the enclosed paradise garden (jannat) featuring quadrants of orchards and flowerbeds, intersected by water channels and walkways, with pavilions or viewing porches for enjoying the scenery. One famous example is the Court of the Long Pond (Patio de la Acequia) in the Generalife, a long rectangular garden court with a central water channel flanked by two rows of jets that arc water into the air. Framed by myrtle hedges and seasonal flowers, and terminating in a shaded arcade and mirador, this court offered the Nasrid elite a tranquil refuge where the sound of trickling water and the sight of reflecting pools could soothe the senses. Such garden pavilions were not merely for leisure; they were a statement of cultivated kingship. By mastering water through irrigation canals from the Darro River, the Nasrids turned the dry Andalusian hillside into a lush retreat, underscoring their ability to “recreate the gardens of paradise” in this world.

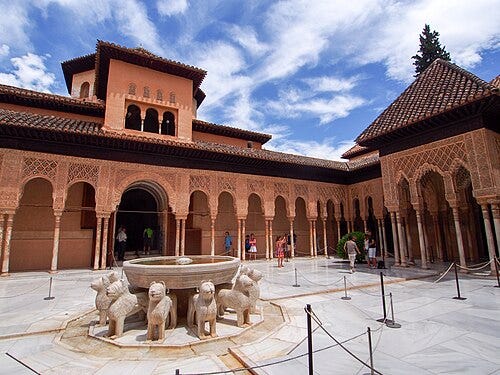

Within the Alhambra proper, the Courtyard of the Lions provides another take on the garden-pavilion idea. At its center is the famed Fountain of the Lions, a large marble basin supported by twelve carved marble lions, set at the intersection of two water channels that quarter the courtyard. Around this symbolic fountain, the open courtyard was originally planted with low shrubs and perhaps citrus trees, creating a garden milieu within the heart of the palace. Four halls (the Sala de dos Hermanas, Sala de los Abencerrajes, etc.) open onto the Lion Courtyard, each with a shaded portico, effectively making the fountain court a outdoor living room. The pavilion-like Hall of the Abencerrajes and Hall of the Two Sisters both connect directly to this courtyard and feature large arched openings, allowing cool air and the sound of water to flow inside. This configuration reflects the classic Islamic chahar-bagh (four-part garden) concept translated into architecture: water is the lifeblood of the design, and each architectural pavilion enjoys a view and access to the central garden space. The integration is so complete that it is hard to say where architecture ends and nature begins, a hallmark of Moorish palatial design. The overall effect, as one historian put it, is “a sense of paradise, a common theme in Islamic garden design”, achieved by the delicate balance between water, vegetation, and built forms.

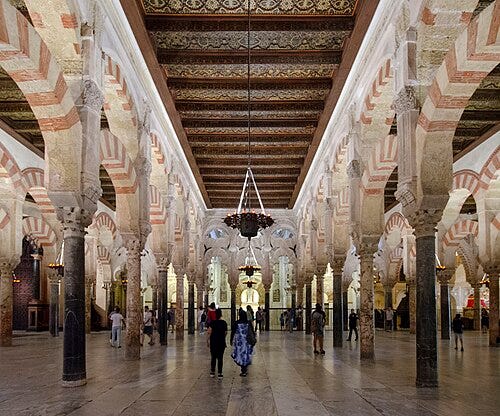

If the Alhambra represents the zenith of late Islamic architecture in Spain, the Great Mosque of Córdoba (la Mezquita) stands as the foundational monument of Al-Andalus, renowned for its expansive hypostyle hall and its forest of candy-striped horseshoe arches. Founded in 785 CE under the Umayyad emir ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I and expanded multiple times through the 10th century, the mosque’s prayer hall eventually grew into a breathtaking grid of some 850 columns supporting double-tiered arcades. The uniform repetition of columns and arches creates a powerful visual rhythm: visitors often describe the sensation of being in an endless grove of palm trees made of stone. In fact, the hypostyle hall has been likened to a “forest of columns” and even to a “hall of mirrors,” as the rows of arches seem to recede infinitely in every direction. This innovative design was not only aesthetically mesmerizing but also highly practical for expansion; each bay of columns and arches could be replicated module by module as the congregation grew. The two-tiered arch system (with a lower horseshoe arch and an upper semi-circular arch) solved a key engineering challenge as well: the recycled Classical and Visigothic columns available in 8th-century Córdoba were relatively short, so by adding a second layer of arches above, builders effectively doubled the height of the interior space. The upper arches also help distribute the weight of the roof and enhance stability, anticipating later Gothic solutions to spanning large interiors.

Horseshoe arches became the signature motif of the Córdoba mosque and subsequently of Moorish architecture in general. A horseshoe arch arcs beyond a semicircle, curving inwards at the base; this form was common in late antique Visigothic churches in Iberia and was adopted and refined by the Umayyads. In the Great Mosque, the horseshoe shape is pronounced and combined with a bold alternating red-and-white voussoir pattern (voussoirs are the wedge-shaped stones of the arch). Constructed from alternating courses of brick and stone, these striped arches were not merely decorative; they likely drew inspiration from the multi-colored arches of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and earlier Roman and Byzantine examples. The result in Córdoba is visually striking: rows of terracotta-red and creamy white bands undulating throughout the mosque, a color scheme that enlivened the otherwise monochromatic space. The pattern also has structural logic; brick lightened the load and added flexibility, while stone lent strength, but its aesthetic impact was paramount. The traditional Visigothic horseshoe arch thus evolved under the Umayyads into “its own distinctive and slightly more sophisticated version” of the form, one that would spread across North Africa and define Western Islamic architecture. Even after the Christian reconquest, this arch type was so emblematic that it continued to be called the “Moorish arch” in Spain.

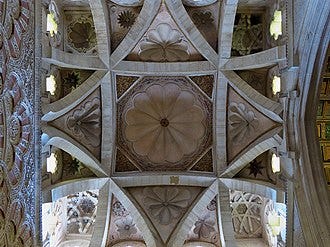

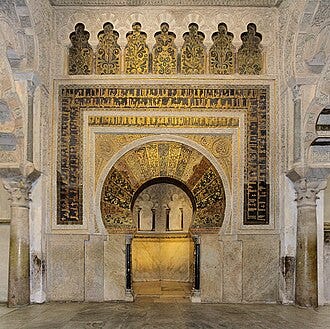

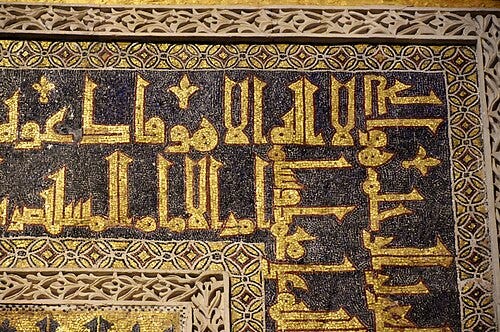

Walking through the hypostyle hall in its prime (it is now a cathedral, with a Renaissance nave inserted in the center), a worshipper would have experienced an awe-inspiring unity of design. Despite the vast scale, the repetitive use of identical arches and columns created a sense of harmony and perhaps a kind of deliberate disorientation. As art historian Jerrilynn Dodds observed, the Córdoba arches seem to defy conventional architecture by subverting expectations of structural logic; the doubled arches and abundant supports have no single focal point, generating “tensions that grow from… subverted expectations” and an intellectual engagement between viewer and building. In practical terms, the openness of the hypostyle plan allowed flexible access and accommodation of thousands of worshippers. Lit by small windows and later by hundreds of brass lamps, the hall would glow in dim golden light, the columns allegedly evoking a contemplative night forest. The 10th-century caliphal expansion under al-Hakam II added a series of ornate domes in front of the mihrab (prayer niche) which introduced new architectural complexities, interlacing arches and ribbed vaults, but even these marvels were integrated into the greater sea of arches. The mihrab itself, remodelled in 965 CE, is a masterpiece of Islamic art: a horseshoe-arched niche framed by a gilded mosaic arch with lavish floral and epigraphic motifs in Byzantine style glass tesserae. This vibrant focal point of blue, gold, and red glass set into marble contrasts with the mosque’s otherwise restrained decoration, highlighting the sacred wall. Flanking the mihrab, screens of intersecting polylobed arches and Byzantine-inspired mosaics further demonstrated the cultural synthesis at work.

Ultimately, the Great Mosque of Córdoba’s architectural design represents a brilliant melding of pre-existing regional traditions with new Islamic ideas. The familiar Visigothic arch and Roman column are transformed and multiplied into something entirely novel, achieving both grandeur and a mysterious beauty. Later observers, including Christian architects in Gothic Spain, were duly impressed. Even Charles V, who authorized building a cathedral nave within the mosque in the 16th century, is said to have regretted the alteration, famously remarking, “You have destroyed something unique to build something commonplace.” Indeed, the original mosque’s spatial magic, its “forest” of red and white horseshoe arches receding in the gloom, remains a tour de force of design that continues to captivate visitors and art historians alike.

Underpinning the architectural magnificence of Al-Andalus’s monuments is a sophisticated aesthetic system that employs calligraphy, geometric pattern, vegetal motifs, light, and water in harmonious concert. In accordance with Islamic artistic traditions, figural imagery was largely avoided in sacred and palatial spaces, giving rise to a decorative repertoire that is at once abstract and deeply symbolic. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Alhambra, where walls literally speak through inscriptions, and the play of light on muqarnas vaults or in reflective pools creates an ever-changing visual poetry.

Epigraphic ornament (calligraphy) is a hallmark of the Alhambra’s interior design. Arabic inscriptions, crafted in stucco relief and tile mosaic, blanket the palace walls to a degree unsurpassed in the Islamic West. These inscriptions range from Qur’anic verses and pious invocations to exquisite lines of court poetry composed by the palace’s own poets. The Nasrid dynasty’s royal motto, “Wa lā ghālib illa Allāh” (“There is no victor but God”), is famously repeated hundreds of times in elegant cursive script along friezes and arch spandrels. In some rooms, such as the Hall of the Ambassadors, entire poems praising the ruler and the beauty of the architecture are carved into the walls, blurring the line between literary art and architectural decoration. The Alhambra’s calligraphy is executed in diverse styles: cursive naskhi and thuluth scripts flow in curvilinear grace, while angular Kufic inscriptions are often knotted into intricate geometric designs, a particularly elaborate variety known as “knotted Kufic” evident in the palace’s epigraphic program. As one scholar observed, the walls of the Alhambra “read like pages of a manuscript,” with geometric zellij tiles forming the “illumination” below and flowing calligraphic text above. This prominent use of writing had multiple purposes: it was decorative, certainly, but also carried meaning and political messaging (glorifying the Nasrid rulers under the mantle of piety). The shimmering inscriptions catch light and cast shadows, so the very act of reading them is dynamic. In the Great Mosque of Córdoba, by contrast, calligraphic ornament is concentrated around the mihrab area, there, gold mosaic inscriptions of Qur’anic verses announce the glory of God above the niche, placed by order of the caliph al-Hakam II. The church that the mosque became later added its own Latin inscriptions, but the Islamic epigraphy remains an integral part of the historical fabric. In all these cases, beautiful script elevates the space spiritually and aesthetically, manifesting the Qur’anic emphasis on the “Word” in a visually splendid form.

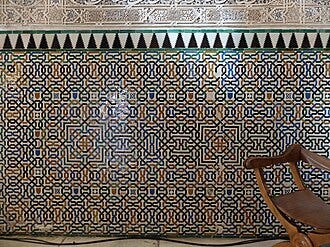

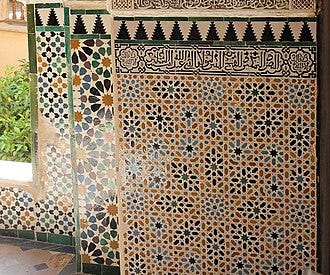

Equally vital to the Andalusi visual language is geometry. Geometric pattern forms the very backbone of Islamic design, providing an endless array of star motifs, polygonal strapwork, and interlacing grids that symbolize the infinite nature of creation. In the Alhambra, zellij tile mosaics enliven the lower wall dados with sophisticated polygonal compositions, eight-pointed stars, interlocking crosses, and multi-sided polygons in saturated ceramic glazes. These tiles, in emerald green, lapis blue, ochre, and white, are arranged in mathematically precise patterns that fascinated even modern scientists (notably, some Alhambra patterns demonstrate principles of quasi-crystalline geometry recognized only in the 20th century). The stucco and wood surfaces above complement this with more free-form but still highly ordered geometry: stucco panels in the Hall of Two Sisters, for instance, feature a twelve-pointed star within a complex web of rhombuses and foliage, all calculated to fit perfectly within an architectural frame. The importance of geometric design went beyond visual appeal; it reflected an intellectual worldview. Each pattern, adhering to “precise mathematical ratios,” creates a sense of balance that was seen as echoing the divine order of the universe. In a culture where geometry and astronomy were advanced sciences, the architects deliberately incorporated proportional systems in the Alhambra’s layout as well, giving the complex a harmonious module-based coherence. The Great Mosque of Córdoba also employed rigorous geometry in its expansion, the rhythm of columns set approximately 3 meters apart and aligned on a grid ensured visual unity, and the extensions under different rulers carefully maintained these proportions. Furthermore, the introduction of ribbed domes in the 10th-century Córdoba mosque brought a new geometric complexity: crisscrossing arches forming star patterns in the ceiling (one dome creates an eight-pointed star by intersecting ribs). These innovations were forerunners to later Gothic rib vaults, again demonstrating how geometric experimentation in Islamic architecture influenced broader architectural developments.

Light and shadow are themselves artistic media in these structures. The architects of the Alhambra were masters of manipulating natural light to animate their designs. As day progresses, sunlight filters through lattice screens (jalousies or mashrabiyas) and from high clerestory windows, projecting arabesque shadows onto floors and illuminating different facets of muqarnas vaults. In the Hall of the Ambassadors (the throne room of the Alhambra), a ring of small windows near the top of the wooden dome allows shafts of light to hit the cedar ceiling’s inlay of stars, making them twinkle like a celestial canopy. Meanwhile, the rest of the hall’s walls remain relatively dim, causing the gilded calligraphy and stucco to stand out in contrasting light. This careful orchestration of darkness and illumination creates an almost theatrical setting that heightens the spiritual and emotional impact. Similarly, in the Great Mosque of Córdoba, the forest of arches creates a chiaroscuro effect: since direct light only enters from the courtyard and some upper windows, most of the hypostyle hall was lit by lamps, meaning columns would emerge from semidarkness as one moved through, an effect akin to walking through a grove at dusk. Al-Hakam II’s addition of skylights in the domes and behind the mihrab (with their gold mosaics) added dramatic illumination exactly at the focal points of prayer. Light in Islamic architecture often symbolizes divine presence or knowledge, and here it is harnessed artfully to guide the faithful and adorn the sacred spaces without need for figurative images.

Finally, water is an oft-overlooked but crucial element of Andalusi architectural aesthetics. In the Alhambra, water features serve both functional purposes (cooling, irrigation) and artistic ones. The Courtyard of the Myrtles (Patio de los Arrayanes) is dominated by a large, still reflective pool at its center. This mirror-like basin not only passively cools the air but also doubles the visual impact of the surrounding portico and Comares Tower, the arches and sky are reflected perfectly on calm days, producing a dreamlike symmetry. The use of such reflective pools draws on earlier Islamic garden traditions and enhances the sense of tranquility and infinity in these courtyards. In the Court of the Lions, the four channels running from the lion fountain subdivide the space and provide the gentle sound of running water, which was known to be psychologically soothing and spiritually evocative of paradise (the Quran describes paradise as having “gardens with rivers flowing beneath”). Water in motion, as seen in the Generalife’s runnels and jets, also catches sunlight, adding sparkle and vitality to the stone architecture. One historian aptly calls the Alhambra’s design a “historic watershaping masterpiece,” noting the Nasrid architects’ ingenious use of gravity-fed hydraulic systems to feed fountains and pools throughout the sprawling complex. The Great Mosque of Córdoba, too, originally incorporated water in its design: the courtyard (Patio de los Naranjos) was equipped with fountains and basins for ablutions (ritual washing) among rows of citrus trees. This courtyard, with its grid of bitter orange trees, can be seen as an extension of the mosque’s orderly design and offered worshippers a refreshing transition from the hot sun to the cool, dim interior. In both monuments, water serves to blur the boundary between architecture and landscape, reflects and activates the decorative surfaces, and reminds users of the Quranic vision of an ideal garden, a powerful, multisensory symbol.

Despite their breathtaking appearance, the grand structures of Al-Andalus were often built from humble materials ingeniously manipulated to simulate grandeur. Materials such as wood, plaster, brick, and tile were used extensively, with judicious additions of marble and mosaic where visual impact or structural needs dictated. In the Alhambra, for example, the imposing fortress walls and delicate palaces alike were constructed primarily of rammed earth (tapial) and brick, then sheathed in stucco and ceramic tile. This method allowed rapid construction and provided a smooth canvas for decoration. Wooden elements (mostly pine) formed the framework for roofs, ceilings, screens, and door leaves. The Nasrid woodwork, especially the carved and painted cedar ceilings, is itself a marvel of technique, featuring intricate marquetry and muqarnas forms assembled from thousands of pieces (the ceiling of the Hall of Ambassadors contains over 8,000 individual wooden components fitted together into a radiant star pattern). Because wood and earth are less durable over time, the survival of the Alhambra owes much to continuous maintenance and careful restoration. By contrast, stone was used sparingly: columns and capitals of the Alhambra were carved from local marble (a durable white Macael marble) to provide slender yet strong supports, and the famous lion fountain and basin are also of marble. In the Córdoba mosque, many columns are spolia (reused shafts of marble, granite, and jasper) scavenged from Roman and Visigothic ruins, giving the mosque a forest of polychrome stone supports topped by Corinthian-like capitals. When additional columns were needed in later enlargements, the Umayyad architects commissioned new ones that imitated classical marble capitals but with slight stylistic departures, hinting at the nascent Islamic decorative style. The horseshoe arches of Córdoba were composed of stone and brick voussoirs as noted, illustrating a clever composite technique.

Foremost among construction arts in these monuments is stucco work, the carving and casting of plaster for decorative relief. Plaster (gypsum or lime mixed with marble dust) had the advantage of being inexpensive, lightweight, and versatile; it could be worked wet or carved when dry, and could take pigments readily. In Nasrid Granada, craftsmen developed two main methods to create the profuse stucco ornament: carving in situ and mold casting. For unique or site-specific motifs, artisans would apply a thick coat of plaster to the wall and then chisel out intricate designs by hand once it set (a process requiring virtuoso skill to achieve the fine lacework patterns). For repeating elements, such as muqarnas cells or bands of repeating epigraphy, they often first designed and cut a master pattern in wood or plaster, then used it to cast multiple identical pieces. The cast plaster units would be set in place on the walls or vaults while still damp using a bit of mortar or clay, and once installed, the craftsmen would recarve and refine the joints so that the pattern achieved a continuous, hand-tooled look. This hybrid technique greatly accelerated the decorating process and allowed for astonishing complexity and uniformity in designs like the muqarnas vaults. After carving, the stucco reliefs were painted with mineral pigments (blues from lapis or oxides, reds from iron oxides, greens from copper compounds, etc.) and sometimes embellished with gilding. Though much of the color has faded, traces remain, and ongoing conservation occasionally reveals brilliant original hues beneath centuries of wash. The use of plaster was not a sign of poverty but of practical adaptation: as one source notes, the Nasrids used “relatively poor” core materials, wood, plaster, brick, hidden beneath a skin of rich ornament so skillfully executed that the overall effect was luxurious and resplendent. In fact, only the floor pavings and columns needed to be of costly marble; everything above could be plaster illusion and cedar carpentry, allowing the builders to cover vast surfaces with decoration on a limited budget.

Another distinctive material technique is tilework. The Alhambra’s zellij mosaics are made of glazed terracotta tiles cut into geometric shapes and assembled like a puzzle,.a labor-intensive process that produced durable, light-reflective decorations especially on lower walls and fountains. The Umayyads in Córdoba likewise used glazed tiles and glass mosaics around the mihrab, and unglazed ceramic tiles for floors. Metalwork and glass were present too (for example, the mosque would have bronze chandeliers and wrought iron grilles, and the Alhambra had gilded brass lanterns and door fittings), though these are less preserved today. Both structures also relied on structural innovations: the double-arch system in Córdoba already mentioned, and in the Alhambra, techniques to insulate and waterproof the earthen walls. For instance, wooden tie-beams and iron clamps were used in the Alhambra to reinforce walls, and rubble cores were faced with fired brick or stone in critical areas. The skill of Andalusi builders is perhaps most evident in how long these edifices have stood. Despite earthquakes, for example, the Great Mosque’s arcades survived largely intact (a tribute to the stabilizing effect of the two-tiered system), and the Alhambra’s palaces, though delicate, have endured centuries of use, misuse, and neglect.

In the present day, the Great Mosque of Córdoba and the Alhambra face substantial conservation and management challenges, as their age and popularity test the limits of preservation. Both are UNESCO World Heritage sites, and Spanish authorities have long recognized their Outstanding Universal Value. Yet the mandate to safeguard their integrity must contend with natural deterioration, past alterations, and the pressures of mass tourism.

One major challenge is the sheer number of visitors these sites attract. The Alhambra in particular is among the most visited monuments in Europe, drawing over 2.7 million visitors annually in recent years. This popularity raises concerns about wear and tear on the fragile stucco and tile surfaces, as well as congestion and environmental impact. To mitigate damage, the Alhambra’s administrators have instituted strict ticketing limits, currently capping visitors at about 2.76 million per year, and require timed entries into the Nasrid Palaces. This system, for conservation reasons, aims to prevent the site from exceeding its capacity (a limit that was indeed breached in 2019 before new measures were taken). Likewise, certain areas of the Alhambra are periodically closed for restoration or rested to reduce strain. The Director of the Alhambra has openly noted that "mass tourism has a negative effect on conservation" and that while tourism is economically necessary, it must be carefully managed to avoid long-term harm to the monument. Visitor flow management, crowd control, and monitoring of humidity and CO₂ levels in confined palace rooms are now integral to the Alhambra’s conservation strategy. The Generalife’s historic gardens also suffer from heavy foot traffic, prompting the use of designated paths and replica planting to protect original horticultural layouts. Balancing public access with preservation is a delicate and ongoing task.

Environmental and biological factors pose another set of challenges. In Córdoba, for instance, a surprising adversary was discovered in the 1990s: termites. While conducting roof repairs on the Mosque-Cathedral, conservation architects found sections of the timber roof framework had been damaged by termite infestation. Although no active colonies were found at the time, the response was swift and thorough, all wooden elements were systematically treated with chemical protectants, and plans were made to insert physical barriers in the soil around the building to prevent any future insect ingress. This episode highlights the continuous vigilance required in preserving historical structures; even tiny insects can threaten a 1200-year-old monument. The Great Mosque, now a working cathedral, also faces the normal wear of daily religious use and liturgical modifications. The insertion of the cathedral nave (16th century) altered structural dynamics and introduced high Gothic vaults that needed their own maintenance. Modern conservation efforts in Córdoba therefore involve not only preserving the Islamic-era fabric (arches, mosaics, wooden ceilings) but also the later Christian elements, essentially maintaining a palimpsest of history without allowing one layer to destroy another. Controversies have arisen, such as debates over whether the Church has appropriately highlighted the Islamic origin of the building in its signage and interpretive materials (heritage professionals and UNESCO have insisted that the term “Mosque–Cathedral” be used to acknowledge its dual identity). This touches on a conservation philosophy issue: the interpretation of the site and the importance of an inclusive historical narrative as part of its preservation.

For the Alhambra, climate and material decay are constant foes. The plasterwork, while largely stable in Granada’s dry climate, still erodes over time, especially any parts exposed to the elements in open courts. Rainwater intrusion and fluctuations in temperature can cause cracks in stucco or loosening of tiles. The patronato (Alhambra’s managing trust) employs teams of restorers who continuously monitor the state of the ornamentation, consolidating areas of flaking plaster or faded paint. In some areas, they undertake reversible restorations, for instance, applying a removable protective coating or lightly repainting motifs to approximate the original look (as was done recently in the Hall of the Kings where the medieval painted ceiling panels were cleaned and conserved). A noteworthy early modern restoration figure was Leopoldo Torres Balbás, who in the 1920s–30s established guiding principles still influential today. Torres Balbás removed unsympathetic 19th-century additions and repairs, choosing to conserve what remained of Nasrid work without excessive reconstruction. His “meticulous approach” emphasized authenticity of materials and respect for the building’s historic state. This set a precedent for future Alhambra projects: any new intervention should be discreet and well-documented. One of the biggest tests of this philosophy was the controversial mid-20th-century replacement of some Alhambra tiles and plaster casts, which critics said were too conjectural. In response, more recent practice leans towards minimum intervention, stabilizing rather than replacing wherever possible.

Beyond the structures themselves, the broader environment of these monuments requires protection. Both sites are embedded in historic urban or natural landscapes (the Alhambra is part of Granada’s hillscape, including the Albaicín quarter; Córdoba’s mosque sits in the old quarter by the Guadalquivir River). Urban development, pollution, and vibration from traffic can all affect them. For example, car traffic around the Córdoba historic center has been limited to reduce vibration that might stress the ancient columns. In Granada, a 1990s proposal to build a nearby tourist complex raised alarms with UNESCO and was ultimately altered, illustrating the need for vigilant planning controls. Additionally, these monuments must adapt to modern requirements in subtle ways; fire prevention systems, seismic reinforcement (Granada is in a mild earthquake zone), and accessibility improvements have all been introduced carefully so as not to disturb historical fabric.

In summary, the conservation of the Great Mosque of Córdoba and the Alhambra today is a multifaceted effort addressing physical restoration, preventive care, and sustainable tourism management. It involves international collaboration (given their World Heritage status) and interdisciplinary expertise, from engineers treating centuries-old wood, to chemists devising gentle cleaning methods for delicate stucco, to policy-makers devising ticketing systems. The goal is to ensure that these masterpieces of Al-Andalus endure for future generations in as authentic a state as possible. As María del Mar Villafranca (former Alhambra director) suggested, finding equilibrium is key: “Tourism is necessary, but it is not the solution to the problems faced by our heritage”, a reminder that economic benefits should never outweigh the responsibility to preserve the profound cultural legacy embodied in these monumental masterpieces.

The architectural gems of Al-Andalus, epitomized by the Great Mosque of Córdoba and the Alhambra, stand as monumental masterpieces of design and innovation. Through a blend of cultural influences and original genius, the Muslim builders of medieval Spain created spaces that were structurally daring, visually mesmerizing, and spiritually uplifting. The Alhambra’s filigree-like stucco, its muqarnas domes, and paradisiacal gardens reflected a refined palatial aesthetic that celebrated light, geometry, and the word of God in every detail. The Great Mosque’s forest of striped horseshoe arches and cool courtyards manifested a new Muslim identity on European soil while ingeniously repurposing local traditions. Both monuments demonstrate how form and decoration in Islamic architecture work together to shape an immersive environment, be it the serenity of a palace courtyard or the sublime repetition of a hypostyle hall. Their legacy influenced artistic developments far beyond Iberia and continues to inspire awe.

Yet, these buildings are not static relics of the past; they are living monuments that have evolved and survived against the odds. The modern era brings its own trials, but also the opportunity for appreciation across cultures and faiths. That the Córdoba Mosque–Cathedral can be cherished today both as a cathedral and as a work of Islamic architecture attests to a complex but rich historical continuity. The enduring beauty of the Alhambra, meanwhile, draws people of all backgrounds, reminding us of a time when the arts of Islam flourished in Europe. In safeguarding these sites, we uphold more than just stones and plaster; we preserve the message of coexistence and the heights of human creativity that Al-Andalus represents. Monumental Masterpieces of Al-Andalus will continue in Part 2, exploring further dimensions of this legacy and its resonance in art, literature, and contemporary design.

Works Cited

Blair, Sheila, and Jonathan Bloom. The Art and Architecture of Islam: 1250–1800. Yale University Press, 1994.

Capping visitor numbers to protect cultural sites from overtourism. El País - English Edition, 9 Oct. 2023. Accessed 2 July 2025.

Herman, Eric. The Alhambra: A Testament to Moorish Splendor. WaterShapes, 2023. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Macaulay-Lewis, Elizabeth, and others. The Great Mosque of Córdoba. Smarthistory (via Humanities LibreTexts), 2018. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last edited 12 June 2025. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Moorish architecture. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Nasrid plasterwork: Symbolism, materials & techniques. Victoria and Albert Museum Conservation Journal, Issue 48, Autumn 2004. (Referenced in Borges, Victor. Islamic Arts & Architecture, 16 Dec. 2011). Accessed 4 March 2025.

Piccavey, Molly. The Alhambra Palace - Secrets behind the Writing on the Wall. Piccavey.com blog, 4 Apr. 2016. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Stucco decoration in Islamic architecture. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 2023. Accessed 4, March 2025.

Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. Restoration of the Alhambra. (Restoration report excerpts, 1923–1936). In Twentieth-Century Architectural Heritage, edited by Margaret Archip, Alhambra Patronato, 2006.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Historic Centre of Cordoba - State of Conservation (SOC), 1994. whc.unesco.org, 1994. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Alhambra. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last edited 12 June 2025. Accessed 4 March 2025.

I’ve never visited the Alhambra, and after reading your evocative description, it’s all I can think about doing now!