Islamic Spain, known as al-Andalus , was not only a period of dazzling artistic achievement (as explored in Part 1), but also a milieu of rich cultural exchange and enduring legacy.

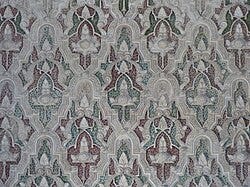

Al-Andalus began in 711 when an army of Arabs and Berbers crossed from North Africa, rapidly conquering most of the Iberian Peninsula under Umayyad auspices. Initially a province of the Damascus-based Umayyad Caliphate, the region soon developed a distinct identity. After the Abbasid revolution in the East in 750, an exiled Umayyad prince, ʿAbd al-Rahman I, escaped to Spain and established himself as Amir in Córdoba in 756, inaugurating an independent Umayyad emirate. Córdoba became his capital and under his firm rule al-Andalus was unified and stabilized, even as diplomatic ties were maintained with Christian neighbors, North Africa, and the distant Abbasid court. Umayyad rulers in Spain, from ʿAbd al-Rahman I through his successors ʿAbd al-Rahman II, III, and al-Hakam II, were great patrons of art, architecture, and learning. The construction of the Great Mosque of Córdoba under ʿAbd al-Rahman I was a crowning achievement of this early period, signaling the birth of a distinctly Hispano-Islamic architectural style. In 929, ʿAbd al-Rahman III boldly reclaimed the caliphal title, elevating al-Andalus to a caliphate that rivaled Baghdad and other Islamic centers. Córdoba in the 10th century became “perhaps the greatest intellectual center of Europe, with celebrated libraries and schools,” and the arts reached an apogee under ʿAbd al-Rahman III and his son al-Hakam II. Luxurious objects like carved ivories, fine textiles, and gleaming metalwork were produced for the Umayyad court, and major architectural projects, from the Mesquita (Great Mosque) expansions to the creation of the palatial city of Madīnat al-Zahrā’, underscored the role of artistic patronage as a pillar of royal legitimacy. The Umayyads of al-Andalus blended influences from the wider Islamic world (emulating Abbasid opulence and drawing inspiration from Fatimid and other courts) with local Iberian artistry, creating an opulent, hybrid visual culture. In short, the early centuries of Islamic Spain were characterized by strong state support for architecture and the arts, establishing a legacy of patronage that would persist in various forms through subsequent dynasties.

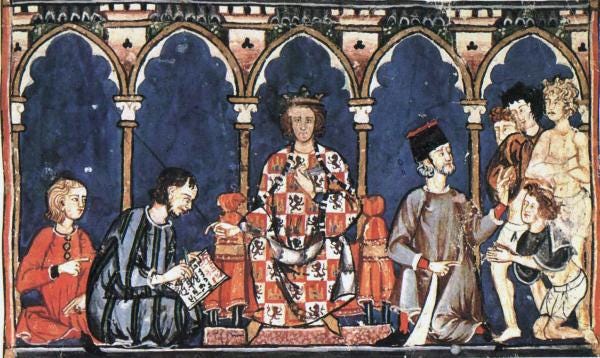

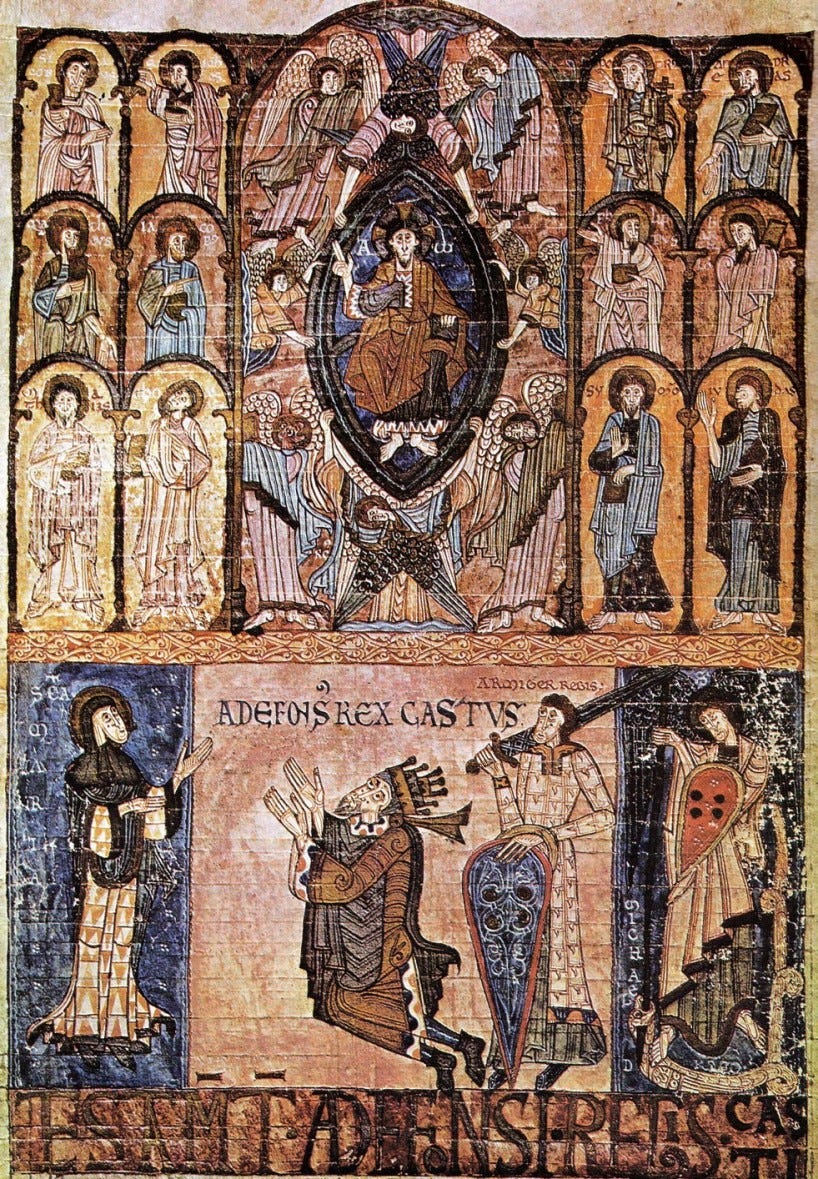

One of the hallmarks of al-Andalus was the coexistence, sometimes harmonious, sometimes fraught, of Muslims, Christians, and Jews within a shared society. For over seven centuries, people of the three faiths lived in Iberia under Muslim governance, generating an environment of interaction that was unique in medieval Europe. Historians debate the extent of convivencia (coexistence or tolerance) in al-Andalus, but it is clear that prolonged contact produced a “unique and diverse culture” blending elements from each community. Despite occasional conflicts or periods of stricter religious policies, long stretches of relative peace allowed for fruitful social and cultural interchange. In major cities like Córdoba, Toledo, and Zaragoza, neighborhoods of Muslims, Christians, and Jews existed in proximity, and daily life prompted frequent encounters across religious lines. Royal courts were especially cosmopolitan; the Umayyad caliphal court in Córdoba welcomed scholars and poets regardless of faith, indeed, it is recorded that some Jewish poets and scholars enjoyed the ear of the caliph, and later the Christian court of Alfonso X of Castile (13th century) similarly included Muslim, Jewish, and Christian sages interacting as colleagues. Such settings became “ideal for cross-cultural interaction,” fostering exchanges of knowledge, artistic techniques, and aesthetic tastes.

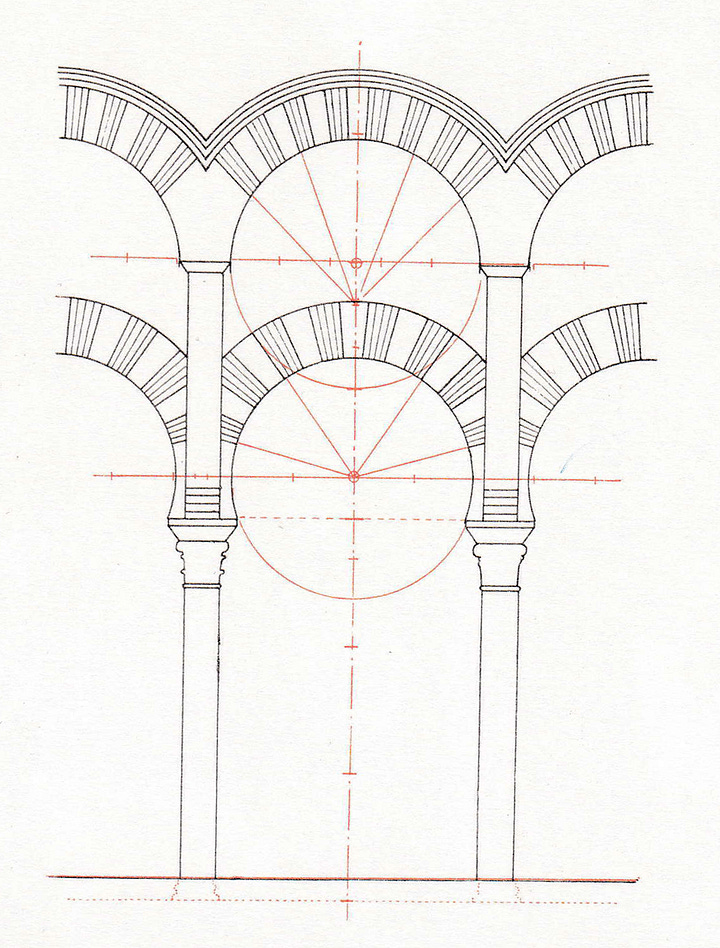

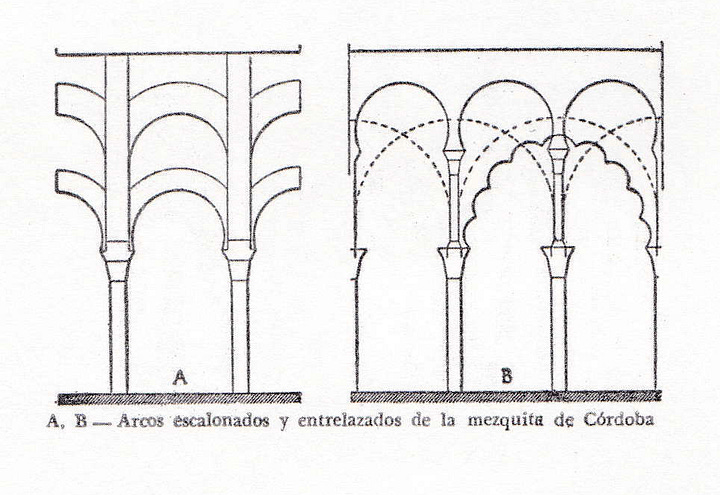

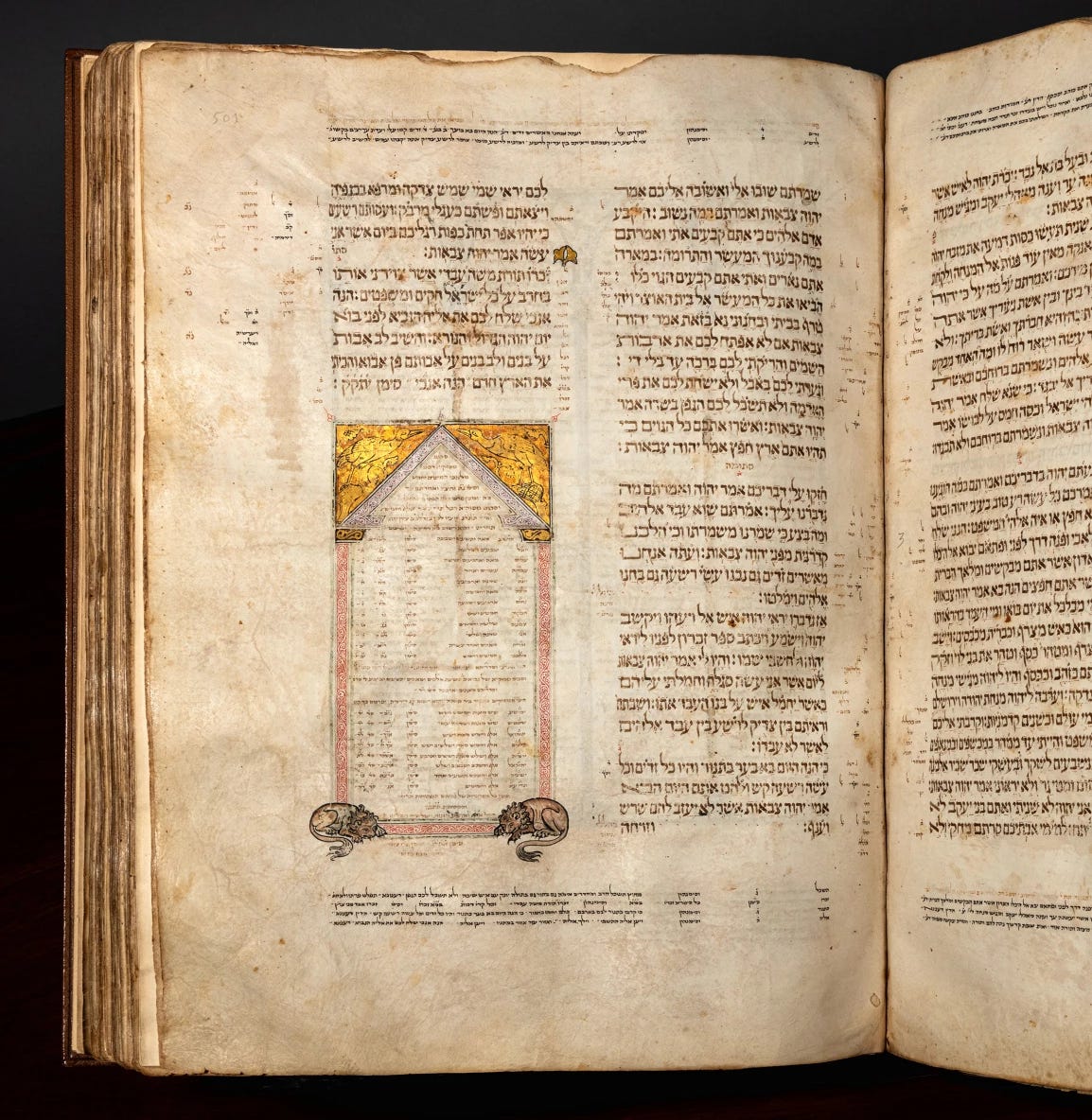

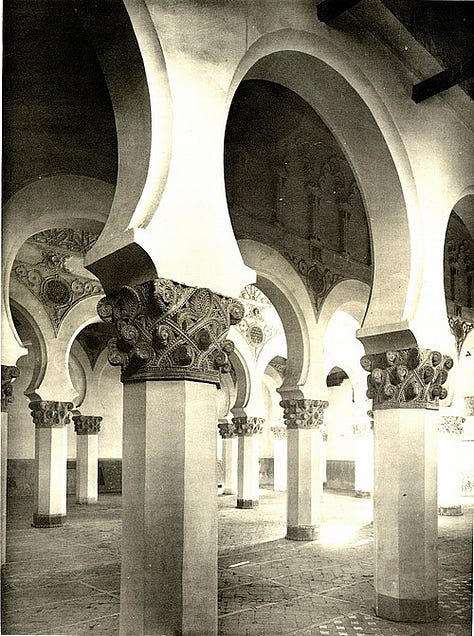

In the arts and architecture, this intercultural exchange was vividly evident. Artisans of different backgrounds borrowed motifs and methods from one another, creating hybrid styles that transcended any single tradition. For example, the Great Mosque of Córdoba, although an Islamic religious monument, may have incorporated architectural features from earlier Visigothic churches on that site (such as the horseshoe arch), reflecting a blending of late antique Iberian heritage with new Islamic forms. Likewise, medieval Hebrew and Christian manuscripts from Iberia have been found to share stylistic features with Islamic illuminated manuscripts, suggesting that the same workshops or artists served patrons of different faiths, or at least that they influenced each other’s visual vocabularies. In the realm of architecture, Jews and Christians under Muslim rule often adopted Andalusi styles; the Mozarabic Christians (those living under Islam) developed church art and liturgical manuscripts infused with Islamic artistic elements, and after Christian re-conquest of cities, the victorious rulers often preserved and repurposed the grand structures of Islamic origin (famously, the Great Mosque of Córdoba was converted into a cathedral in 1236, rather than demolished). Conversely, in the 12th–14th centuries, some synagogues and Christian churches were built or decorated in a distinctly Islamic style, testifying to the ongoing influence of Moorish artisans. For instance, the synagogues of Toledo (such as Santa María la Blanca, rebuilt 1250, and El Tránsito, 1350s) feature horseshoe arches, Arabic ornamental calligraphy, carved stucco panels and geometric tilework indistinguishable from contemporary Islamic architecture. Christian rulers in reconquered areas also commissioned Muslim craftsmen to build in the Islamic style (a trend that gave rise to Mudéjar art, discussed later). Thus, rather than a one-way imposition of culture, medieval Iberia was a “site for the meeting of different cultures” where artistic techniques, materials, and decorative themes were exchanged and adapted in all directions. By the time the last Muslim kingdom fell in 1492, al-Andalus had long functioned as a bridge between the Islamic and Christian worlds, transmitting not only scientific and philosophical knowledge (e.g. via translations of Arabic texts or the works of Andalusi polymaths like Averroes and Maimonides) but also a shared artistic heritage that would leave a lasting imprint on Spanish art and architecture.

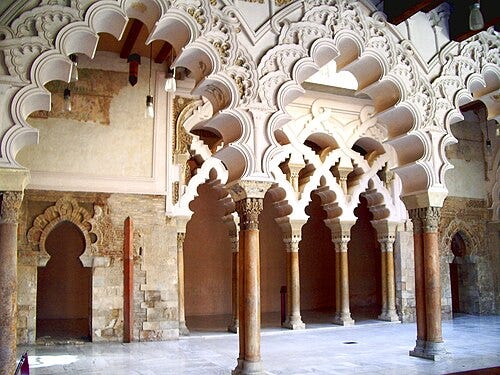

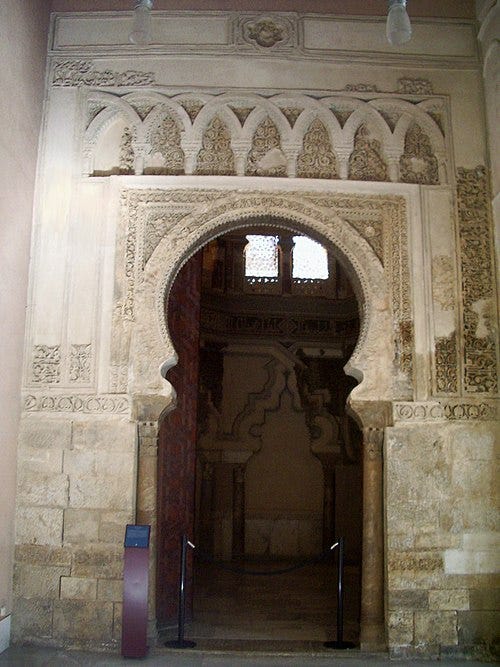

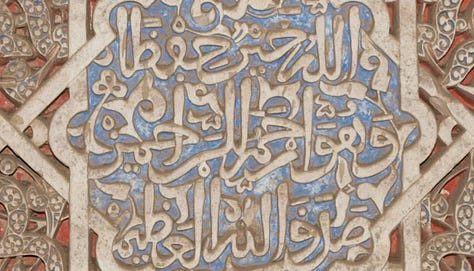

While the Alhambra of Granada often steals the spotlight as the exemplar of Moorish palace architecture, other palatial complexes in Islamic Spain equally illustrate the cultural florescence of their eras. Notably, the Palacio de la Aljafería in Zaragoza and the Real Alcázar of Seville are two such treasures from outside the Nasrid Granada context. The Aljafería, built in the 11th century (second half, ca. 1065–1081) by Abu Jaʿfar al-Muqtadir, the Hudid ruler of the Taifa of Zaragoza, is the only large-scale Islamic palace from the fractious Taifa kingdom period that has survived in Spain. Al-Muqtadir intended this residence as a statement of his power and enlightened taste; he even named it Qaṣr al-Surūr (“Palace of Joy”) and called the richly decorated throne hall Maylis al-Dhahab (“Golden Hall”), celebrating the complex in verses: “Oh Palace of Joy! … because of you, I reached the maximum of my wishes… for me you are everything I could wish for.” These lines, reportedly written by the emir himself, underscore how intimately poetry and architecture were linked in court culture. Architecturally, the Aljafería followed the template of earlier Umayyad desert palaces in the Middle East (a quadrangular fortress-palace with rounded towers and a central courtyard). Its design featured a rectangular open courtyard (with pools and gardens) around which royal living quarters and arcaded porticoes were symmetrically arranged. The decoration was exquisite: scalloped horseshoe arches with lace-like carved stucco, arabesque reliefs once painted in vivid colors and gold, and bands of calligraphy (Kufic inscriptions of Qur’anic verses and dedicatory lines naming al-Muqtadir) running along the walls. In its heyday, at the close of the 11th century, the Aljafería’s halls glowed with polychrome stuccowork against red and blue backgrounds, marble floors, and soffits of alabaster; a truly golden ambiance for the Taifa court. After Zaragoza was conquered by Christian forces in 1118, the Aljafería continued to be used by the Aragonese kings and underwent modifications, including Mudéjar-style additions in the 14th century and later Renaissance fortification under King Philip II. Thanks to extensive 20th-century restoration, the Aljafería today stands as a UNESCO-listed monument (as part of the Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon) and a vivid reminder of the brilliance of a smaller Muslim kingdom’s patronage. It is a critical complement to the more famous Andalusi palaces, showing how Islamic artistic traditions thrived even on the political periphery of al-Andalus.

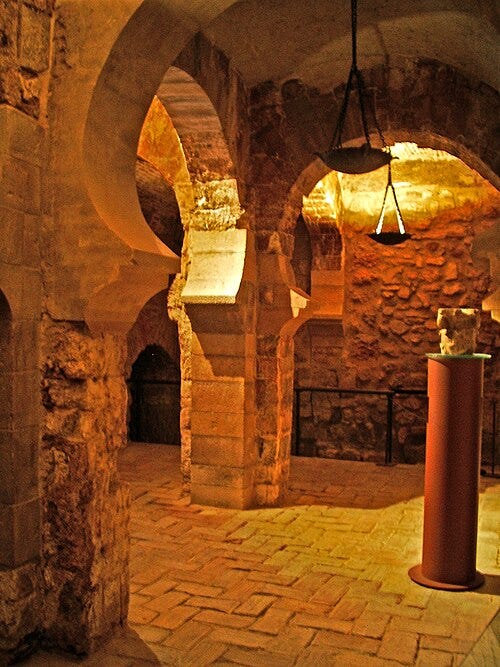

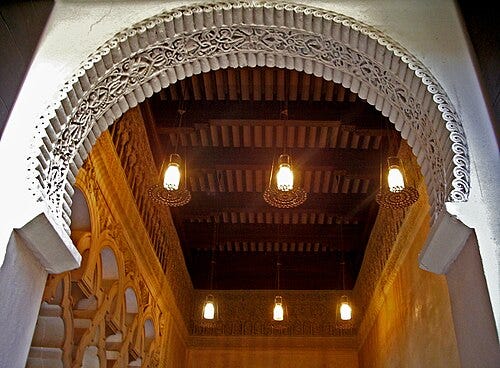

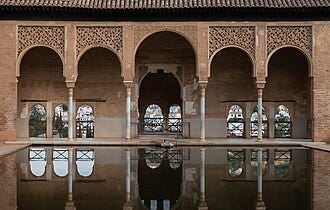

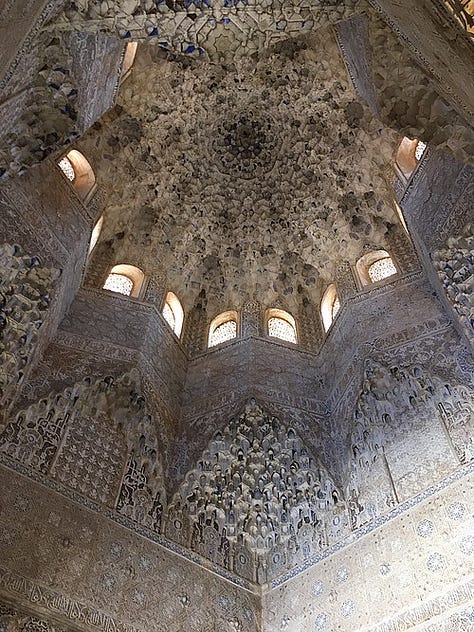

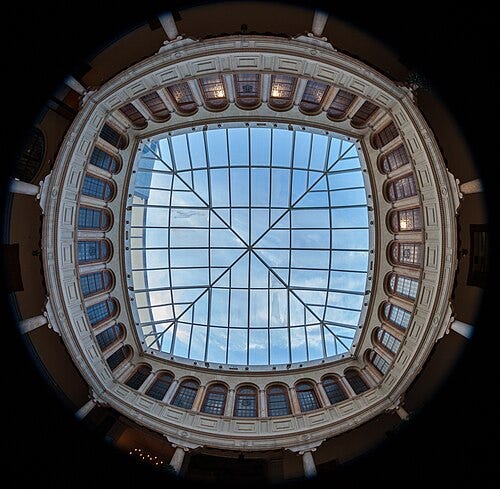

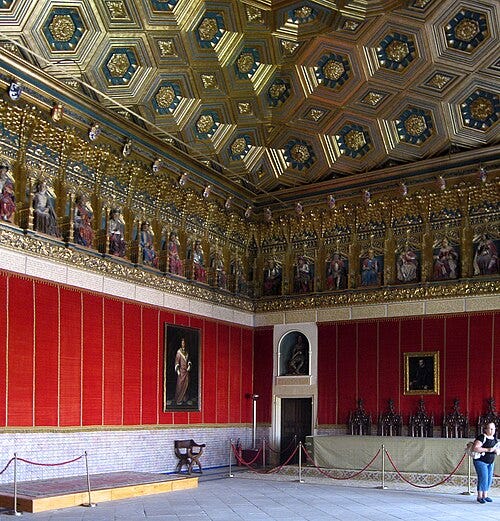

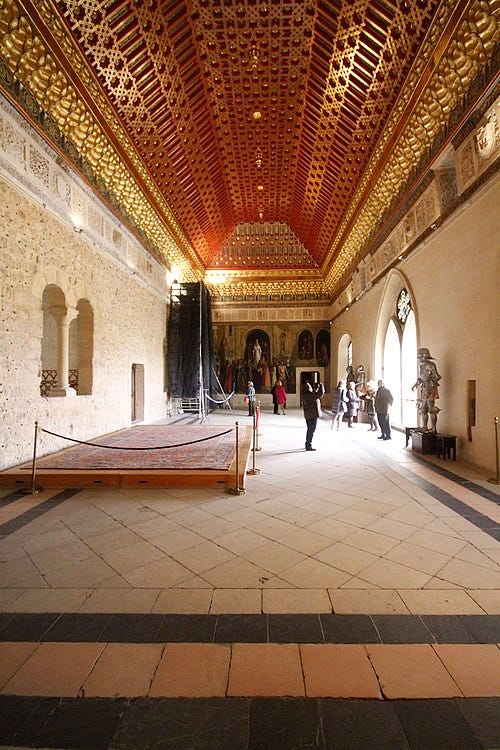

Equally fascinating is the Real Alcázar of Seville, a palace complex that encapsulates layers of Islamic and Christian history. Seville was an important city of al-Andalus: it had an Umayyad-era citadel and later served as a capital for the Almohad caliphs in the 12th century. When Christian King Ferdinand III conquered Seville in 1248, the existing Almohad palaces and fortifications were not destroyed wholesale; instead, over time, Christian rulers adapted and expanded the palace grounds. The most significant addition came in the 1360s, when King Pedro I of Castile (often called “Pedro the Cruel” or “Pedro the Just”) commissioned an entirely new palace block in the Mudéjar style. Pedro’s palace, built by Muslim and Mudéjar craftsmen (some possibly sent by his ally, the Nasrid Sultan Muhammad V of Granada), is a tour-de-force of Hispano-Islamic design, despite being created under Christian patronage. It features exquisite horseshoe and poly-lobed arches, courtyards with central reflecting pools (such as the famous Patio de las Doncellas, “Courtyard of the Maidens”), arabesque tilework (azulejos), carved stucco walls with Arabic inscriptions, and magnificent artesonado (wooden coffered) ceilings. One of its most breathtaking elements is the dome of the Salón de Embajadores (Ambassadors’ Hall); a grand hall used for royal audiences. This dome is a wooden cupola of interlacing geometric stars and muqarnas (honeycomb) forms, covered in gold leaf, resembling the night sky filled with stars. It was crafted by Muslim artisans and symbolically elevates the king (seated beneath) to cosmic significance. Tellingly, an Arabic inscription in the palace actually names Pedro I with the title “sultan” (in Arabic), calling him “Sultan Don Pedro” , which demonstrates the degree to which Islamic royal idioms were embraced to legitimize Christian power. The Alcázar of Seville, as it stands today, is thus a palimpsest; its gardens and many structures hail from the Muslim period (Almohad walls, reservoirs, and earlier Abbadid palace remnants), but its centerpiece is the Mudéjar palace of Pedro I, seamlessly blending Islamic aesthetics with Christian royal ambitions. This site, also designated a UNESCO World Heritage site, is still used by the Spanish royal family on visits to Seville, making it perhaps the oldest royal palace in continuous use in Europe. The Alcázar and the Aljafería together illustrate how Islamic palatial art was not limited to the Alhambra – it flourished across al-Andalus in varied forms, and in Seville it even survived the Reconquista, reinvented under Christian patronage without losing its essentially Moorish character.

Beyond individual monuments, Islamic Spain’s legacy is also embedded in the very street plans and urban layouts of its historic cities. Many old quarters in Andalusian cities still preserve the labyrinthine, inward-focused design inherited from medieval Islamic urbanism. In contrast to the grid-like avenues of Roman city planning or the open plazas of later Spanish developments, the Moorish city was characterized by narrow, winding streets that maximized shade and ventilation, an adaptation to the hot climate, and by an emphasis on privacy and introspection in domestic architecture. In cities like Córdoba and Granada, these features remain strikingly visible.

Córdoba, the Umayyad capital, retains a large portion of its medieval core with irregular streets, cul-de-sacs, and courtyard houses. The UNESCO-listed historic centre of Córdoba has “conserved its medieval plan and the irregular layout of its narrow streets,” with winding lanes that snake around whitewashed buildings. Many houses are built around private patios (courtyards), often filled with fountains and orange trees, reflecting the Islamic tradition of the rahba (courtyard) as the heart of the home and echoing the paradise gardens of Qur’anic imagery. These interior courtyards created cool microclimates and allowed family life to be inward facing, a concept encapsulated in the Arabic term janna (garden/paradise) and still celebrated in Córdoba’s annual Spring Patio Festival. Public spaces in Islamic Córdoba were also advanced for their time: contemporary accounts and later research indicate that by the 10th century the city had paved, lamp-lit streets and hundreds of public baths, and it was reputed to have “300 mosques and innumerable palaces”, rivaling Constantinople and Baghdad in splendor. A great bridge over the Guadalquivir (built on Roman foundations but improved under the Moors) connected the city and remains an iconic landmark today. Across the river to the west lay the vast palace-city of Madīnat al-Zahrā’ (Medina Azahara), built by ʿAbd al-Rahman III, a planned suburban royal city with its own carefully engineered infrastructure of roads, aqueducts, and terraced architecture integrated into the landscape. Though Medina Azahara fell to ruin in the 11th century, its recent excavation reveals a meticulous urban layout combining ceremonial grandeur with sophisticated water supply and gardens, underscoring the high level of Umayyad-era urban planning.

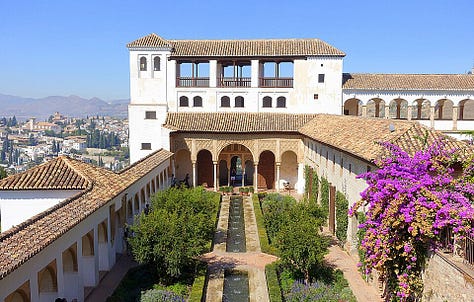

In Granada, the final Muslim capital in Spain, Moorish urban principles are exemplified by the Albayzín quarter. The Albayzín (or Albaicín) is a picturesque district of white houses spilling down a hillside opposite the Alhambra. It was the old Muslim city (a residential quarter and marketplace) and retains a medieval Moorish townscape almost intact. This includes a maze of twisting alleys, small plazas, and an organic street network adapted to the terrain. Granada’s Albayzín is “one of the best illustrations of Moorish town planning,” with narrow streets and small squares and modest traditional houses (casas moriscas) that often feature inner patios and minimal decoration on the outside. The urban structure, as UNESCO notes, has remained essentially unchanged through the centuries, “preserving the appearance of the medieval Moorish settlement” even as later Christian-era additions (Renaissance and Baroque churches, new convents, etc.) were woven into the fabric. For example, after 1492, some mosques were converted to churches in the Albayzín, but the street pattern and many original buildings persisted; one can still find segments of old walls, water cisterns (aljibes), and even a few Arab baths in the area as relics of Moorish Granada’s infrastructure. Notably, the Generalife (the Nasrid emirs’ summer estate on a hillside above the Albayzín) showcases how landscape design and irrigation were integral to Moorish urbanism, its terraced gardens and abundant water channels were part of a “real urban system integrating architecture and landscape,” dependent on sophisticated hydraulic engineering that distributed water throughout the hill-city. Much of the beauty of places like the Albayzín lies in these hidden utilities; acequias (canals) bringing water from the mountains, wells and fountains endowed by charitable waqf (endowments) to ensure public access to water, etc., which made densely built cities livable. In fact, historical records show that in Al-Andalus, city planning often went hand-in-hand with waqf-funded infrastructure projects, for instance, Caliph al-Hakam II established an endowment for constructing and maintaining an aqueduct system to supply Córdoba with water, and many wells, public fountains, and baths in cities like Córdoba, Seville, and Granada were sustained by pious endowments. These measures allowed the medieval Islamic city to achieve a relatively high standard of urban comfort and aesthetics (cool, shaded streets, plentiful water, green spaces) that astonished visitors from elsewhere in Europe. Today, walking through the old quarters of Córdoba or Granada, with their irregular lanes, hidden courtyards, and the occasional scent of jasmine over garden walls, one can still feel the imprint of Moorish urban ideals: a city that is a “hidden paradise” of intimate spaces, rather than grand façades; a city that works with nature (climate, terrain, water) to create beauty and respite, leaving a human-scaled, romantic environment that remains one of the living legacies of al-Andalus.

Islamic Spain’s cultural efflorescence was supported by not only royal patronage but also by institutional mechanisms and intellectual traditions that tied art to piety and poetry to place. One notable institution was the system of waqf (pious endowments). A waqf in Islamic law is a charitable trust in which a donor endows property or revenue for a public benefit, often for religious, educational, or welfare purposes, in perpetuity. In al-Andalus, as in other parts of the Muslim world, awqāf (plural of waqf) played a pivotal role in funding and sustaining architecture and urban amenities. Mosques, madrasas (schools), hospitals, and bathhouses frequently had dedicated waqf funding for their maintenance. For example, historical sources indicate that waqf endowments were used in Al-Andalus to dig wells and build water infrastructures across cities like Córdoba, Granada, and Seville. These endowments ensured the continuous availability of vital resources: they underwrote aqueduct repairs, the operation of sabeels (public fountains) and hammams (bathhouses), and even the salaries of personnel who maintained these facilities. As mentioned, Caliph al-Hakam II’s waqf for the aqueduct of Córdoba is one concrete example, the waqf provided funds so that the aqueduct could reliably supply the city with water for ablutions, drinking, and irrigation. Similarly, in Nasrid Granada, certain public baths (like the 13th-century Hammam al-Andalus near the Alhambra) were supported by waqf, which secured water from nearby rivers to keep the bath running. The waqf system thus created a stable financial foundation for urban institutions and infrastructure, fostering an environment where architecture was not just built but continuously cared for as a religious and civic duty. This legacy persisted even after the Reconquista; many former Islamic buildings that became churches or civic buildings continued to benefit from their original endowments (transferred or repurposed under Christian administration). The concept of endowing a building for the public good has echoes in the later Spanish tradition of obra pía (pious works) and in the endowed foundations that maintain historical sites today. In essence, the waqf system in al-Andalus ensured that architecture and urban planning were deeply intertwined with charitable giving and social welfare – a philosophy that valued continuity, upkeep, and the public interest.

Another distinctive feature of Islamic Spain’s cultural context was the intimate relationship between poetry and architecture. In the courts of al-Andalus, architecture was not seen as mute stone; it was given voice through epigraphy and poetry. Palace walls, garden pavilions, and even objects were often inscribed with verses that personified the building or described its beauty in metaphorical terms. This poetry–architecture nexus reached its zenith in the 14th-century Nasrid palaces of Granada’s Alhambra, but its roots go back much earlier (as we saw with al-Muqtadir’s poetic naming of the Aljafería in the 11th century). The Alhambra is famously embroidered with texts, an estimated 10,000 inscriptions grace its halls and courtyards. These inscriptions include verses from the Qur’an, pious phrases, the Nasrid dynasty’s motto (“Wa lā ghālib illā Allāh” - “No conqueror but God”), and a great many original poems composed by court poets like Ibn al-Khatīb and Ibn Zamrak. The poems often speak in the voice of the palace itself or of its decorative elements. For example, on the Fountain of the Lions, a poem by Ibn Zamrak has the water marvel at its own clear flow and the marble basin “standing like a lover” yearning for the water, a conceit that turns architecture into an animated, speaking subject. These verses both praised the patrons (the Nasrid sultans) and elevated the aesthetic experience of the space, effectively melding literature with architecture into a single artistic experience. Visitors to the Alhambra historically described the walls as seemingly “covered in lace” due to the dense, delicate calligraphy, indeed, “it’s hard to find an inch that is free from inscription in the Alhambra,” notes one modern researcher. The inscriptions do more than embellish; they reinforce the identity and ideology of the Nasrid realm (for instance, extolling the power of God and the glory of the monarch in the same breath). This practice of integrating poetry with architecture was not unique to the Alhambra, but it was unusual in its extent. As art historian Oleg Grabar observed, while poetic inscriptions exist in other Islamic contexts, the sheer scale and complexity of the Alhambra’s epigraphy is exceptional, making the palace a literal text to be read as much as a building to be inhabited. The tradition can be traced in earlier Andalusi monuments too; fragments of poems have been found on architectural pieces from Madīnat al-Zahrā’, and Taifa kings like al-Muʿtamid of Seville were themselves accomplished poets who patronized architecture and likely adorned their palaces with verses. The Aljafería’s throne hall similarly had epigraphic friezes (now in museums) which included Quranic verses and possibly poetic lines, as implied by contemporary chronicles. This poetry–architecture nexus speaks to the broader Andalusi culture in which adab (literary refinement) was highly prized. Educated elites viewed the ability to appreciate and compose poetry as going hand-in-hand with appreciating fine architecture and gardens. The result was a multisensory artistic expression; one could stroll through a palace and literally be reading poetry off the walls, while hearing water trickle in fountains that the poems describe, and feeling the cool marble underfoot that the verses praise. In this way, Islamic Spain’s legacy includes not just the physical structures of its buildings, but also an enduring lesson in how to give those structures meaning through the power of the written word. The impact of this lives on; modern visitors often cite the Alhambra’s inscriptions (now fully catalogued and translated by scholars) as a source of wonder, and the idea of inscribing moral or poetic sayings on buildings remains common in the Hispanic world (consider the mottos on university buildings or the tiles in Andalusian homes with poems and proverbs - a humble continuation of the tradition begun by the poets of al-Andalus).

The year 1492 marked the formal end of Muslim sovereign rule in Iberia with the fall of Granada. However, it did not mark the end of Islamic artistic influence in Spain. In fact, for decades and even centuries afterward, the stylistic language of al-Andalus persisted under Christian rule through what is known as Mudéjar art and architecture. Mudéjar (from Arabic mudajjan, “domesticated” or “tamed”) was the term given to Muslims who remained in Iberia after the Christian reconquests, living under Christian kings while often continuing to practice Islam (at least until forced conversions occurred). These Mudéjars, along with many Moriscos (Muslim converts to Christianity and their descendants), were highly skilled craftsmen, especially in fields like carpentry, tile-making, plaster carving, and building construction. Christian rulers and church authorities, far from discarding the Moorish aesthetic, frequently employed Mudéjar artisans to build new structures or modify existing ones. As a result, a hybrid style flourished in the 14th–16th centuries; Mudéjar style is essentially Islamic Moorish design adapted for Christian contexts. It uses the same horseshoe and polylobed arches, stucco calligraphy and vegetal motifs, wood lattice ceilings, and glazed tile mosaics that had decorated Islamic palaces and mosques – but now they appear in churches, monasteries, synagogues, and royal castles of post-Reconquista Spain.

We have already seen one shining example of Mudéjar architecture in Pedro I’s Alcázar of Seville, which was built in the 1360s by Muslim craftsmen to rival the beauty of any Moorish palace. Similarly, in other cities: Toledo’s Cathedral (13th c.) has Mudéjar Gothic portal decorations; Teruel in Aragon developed a whole school of Mudéjar architecture, with brick towers encrusted in ceramic tile patterns and Islamic-style arches (the Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon is recognized by UNESCO for its uniqueness). Many of the old minarets of mosques were kept and repurposed as church bell towers, such as Seville’s iconic Giralda (originally the Almohad mosque’s minaret, later topped with a Renaissance belfry); a practice that physically merged Islamic and Christian structures. Even Jewish architecture partook in Mudéjar forms: as noted, synagogues in the 13th–14th centuries, like those in Toledo and Córdoba, were constructed by Mudéjar artisans in the prevailing Islamic fashion. This indicates that Mudéjar style was not seen merely as “Muslim” architecture, but rather as a regional style of craftsmanship available to any patron. In Castile, the 15th-century royal palaces in Segovia and Madrid (the now-ruined Alcázar of Madrid) had Mudéjar roofs and ornament. Ceilings with intricate woodwork (artesonado) were especially popular, some splendid Mudéjar coffered ceilings survive in the Alcázar of Segovia and the Palace of the Dukes of Alcala. The Mudéjar style essentially kept alive Moorish artistic principles well into the Renaissance period: for instance, churches built in Mudéjar style have pointed Gothic vaults on the exterior but inside are adorned with bands of arabesque tile and stalactite plasterwork reminiscent of the Alhambra. This fusion is evident in places like the Church of San Román in Toledo or Church of Santa Ana in Seville, where Islamic ornamental motifs and lettering blend with Christian iconography.

The endurance of Mudéjar art underscores that the Christian conquest did not erase the visual culture of al-Andalus; instead, the conquerors to a large extent appropriated and continued it. For the Christian kings, adopting Mudéjar style was politically convenient and aesthetically logical, it showcased the riches of their newly acquired territories and symbolized a continuity of imperial grandeur. The Crown of Aragon in particular (which included Zaragoza, Valencia, etc.) saw prolific Mudéjar construction into the 15th century, which is why Aragon’s Mudéjar monuments (like the Aljafería itself, later fitted with Mudéjar additions by Christian kings) are so prominent. Even after the eventual expulsion of the last Moriscos in 1609, the imprint of Mudéjar style remained deeply ingrained in Spanish architecture. Later centuries revisited it in revival movements, the Neo-Mudéjar style of the 19th century in Spain (and even in Latin America) deliberately emulated the old Moorish motifs, building synagogues, villas, and railway stations with horseshoe arches and tile domes. In a way, Mudéjar art provided a cultural bridge: it allowed Spanish Christians to claim the heritage of al-Andalus as part of their own legacy. Thus, through Mudéjar, the artistic vocabulary of Islamic Spain continued to flourish on Spanish soil long after the political reality of al-Andalus was gone.

Half a millennium since the end of Islamic rule, the legacy of al-Andalus remains a vibrant part of modern Spain’s cultural landscape. One of the most visible aspects of this legacy is in tourism and popular imagination. The great monuments of Islamic Spain, the Alhambra of Granada, the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba, the Giralda of Seville, the Alcázar palaces, among others, are major tourist attractions that draw millions of visitors from around the world each year. The Alhambra, for instance, after a period of neglect, gained international fame in the 19th century thanks to Romantic travelers like Washington Irving (whose Tales of the Alhambra in 1832 sparked widespread interest) and has since become one of Spain’s most visited sites and a World Heritage Site. These monuments are carefully preserved as national treasures; visiting them has become almost a rite of passage for those exploring Spain’s history. In Granada, the Alhambra and Generalife gardens, with their mountain backdrop and rose-tinted walls, are marketed as a symbol of Spain’s exotic and multicultural past, fueling a thriving tourism economy. In Córdoba, the sight of the medieval mosque’s endless arches and its juxtaposition with a Renaissance cathedral nave inspires awe at the layered identity of the place, and it remains an active cathedral today, bridging past and present. The identity of Andalusia (the autonomous region in southern Spain) is in many ways proudly tied to its Moorish heritage: from architectural motifs in city logos and local crafts (ceramics, textiles, leatherwork) that echo Islamic patterns, to the names of restaurants, hotels, and flamenco tablaos that borrow Arabic words and themes. Cities like Granada and Córdoba host festivals and cultural events highlighting their Islamic past (e.g., music festivals featuring Andalusi or Morisco-inspired music, historical reenactments, and academic conferences on al-Andalus).

The legacy also lives in the arts and everyday culture of Spain. Take, for example, music and dance; scholars and artists often note the influence of Arabic and North African musical traditions on flamenco, the quintessential Andalusian art form. Flamenco’s soulful laments and complex, improvised vocal melismas are frequently said to carry echoes of Moorish musical modes (as well as Gypsy, Jewish, and indigenous Andalusian elements). Even the ubiquitous flamenco exclamation “¡Olé!” has been suggested to derive from Arabic, possibly from wa-llāh (by God) or an expression of divine praise. Whether or not that etymology is accurate, it symbolizes the perceived continuity; that in the passionate cries of a flamenco cantaor one might hear the distant strains of an Islamic muezzin or poet. In Spanish language, too, the legacy is immense. It is well known that Spanish absorbed thousands of Arabic loanwords during the Middle Ages, words like ojalá (from in shā’a Allāh, meaning “God willing”), aceite (oil, from az-zayt), acequia (irrigation ditch), algebra, azul (blue), naranja (orange), aduana (customs), and about 4,000 others. Many place names in Spain still carry their Arabic origin; Guadalquivir (al-Wadi al-Kabir, the great river), Albacete (al-Basīṭ, the plain), Almería (al-Mariyya, the watchtower), Granada (maybe from Karnata or Gharnāṭa), Madrid (from al-Majrīṭ). This linguistic heritage means that everyday Spanish speech unwittingly preserves pieces of al-Andalus, a fact often taught with pride in Spanish schools as part of the nation’s diverse cultural genealogy.

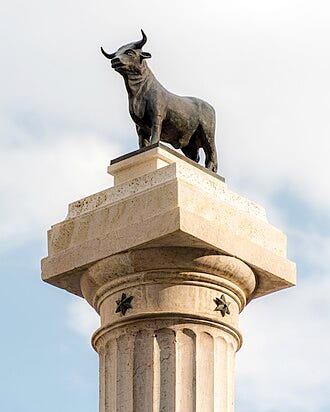

Modern Spanish visual arts and architecture have also drawn inspiration from the Moorish legacy. In the late 19th century, the Neo-Mudéjar movement saw architects design buildings in a revivalist Islamic style, examples include the Las Ventas bullring in Madrid and numerous villas, train stations, and exhibition pavilions across Spain featuring horseshoe arches and tilework (even Antoni Gaudí was influenced by Mudéjar and Orientalist designs early in his career). In contemporary times, artists and designers incorporate Andalusi motifs into fashion, graphic design, and interior decor, celebrating the geometric patterning and calligraphy as a kind of timeless Spanish arabesque. On a more grassroots level, Andalusian identity strongly embraces its al-Andalus heritage; many Andalusians view the period as a golden age of tolerance and culture to be proud of. This is sometimes cast in contrast to the narrative of a purely Catholic, Castilian Spain, highlighting that Spain’s history is not monolithic but a mosaic including Islamic and Jewish pieces. The legacy of al-Andalus has even become a point of diplomatic and cross-cultural emphasis: Spain often positions itself as a natural bridge between Europe and the Arab world, citing the shared history of al-Andalus. Institutions like the Three Cultures Foundation (Fundación Tres Culturas) in Seville celebrate the intercultural dialogue of al-Andalus, and the Spanish government, in promoting cultural tourism or international exhibitions, will leverage the allure of Islamic Spain as part of the country’s unique selling points. Meanwhile, in the realm of ideas, there’s a growing public appreciation for how al-Andalus contributed to the making of modern Spain, for instance, books and documentaries extol how Andalusi scientists preserved classical knowledge and how concepts like religious coexistence have contemporary resonance. One striking modern coda to the story is that in Granada, a new mosque was built in 2003, the first in that city since 1492, by a community of Spanish Muslims (including converts), who consciously reconnect with the Andalusi legacy and even chose a location in the Albayzín with a view of the Alhambra, thus closing a historical circle. Such developments show that the legacy of Islamic Spain is not locked in the past; it continues to evolve and inform identities. As one observer noted, Andalus today is remembered both “as a living legacy, and as a painful awareness of an amputation”,meaning that while the physical presence of al-Andalus ended, its cultural resonance endures, leaving both inspiration and a sense of historical loss. Nonetheless, the dominant note in contemporary Spain is celebratory: the moorish heritage is embraced as an integral strand of Spanish culture, manifest in language, art, architecture, and a richer understanding of what it means to be Spanish, not simply the heir of Christian Europe, but also of the brilliant civilization of al-Andalus.

From the founding of al-Andalus in 711 to the currents of today’s Andalusian culture, the influence of Islamic Spain has been profound and pervasive. Far from being a lost chapter, al-Andalus remains a vital part of the Spanish narrative, a source of pride and wonder. Its legacy is visible not only in stones and relics but in intangible threads woven into the fabric of modern life; a testament to the enduring power of cultural fusion and the arts to transcend their time. As Spain and the world continue to study and celebrate al-Andalus, the lessons of that era, in tolerance, in artistic innovation, and in the beauty of diversity, remain as relevant as ever, ensuring that the spirit of Islamic Spain lives on, appreciated and reinterpreted by each generation.

References:

Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Art of the Umayyad Period in Spain (711–1031). Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2001) .

Senac, Philippe. Al-Andalus. Britannica, 20 Jul. 1998, updated 2 May 2023. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Dodds, Jerrilynn, ed. Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992.

Social and cultural exchange in al-Andalus. Wikipedia, last modified July 2024. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Aljafería. Wikipedia, last modified May 2023.

Alcázar of Seville. Wikipedia, last modified June 2023. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Almagro, Antonio. Moorish Architecture in Andalusian Cities. Vamos Spanish, 2023.

Historic Centre of Cordoba. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, whc.unesco.org. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Ahmed, Akbar. Journey into Europe: Islam, Immigration, and Identity. (Documentary film), 2018.

Waqf (Endowment) for Sustainable Water Management. Muslim Heritage, Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, 2023.

Castilla Brazales, Juan. Corpus of Inscriptions of the Alhambra. CSIC, 2002. (Summary in El País, 2016).

Fernández-Puertas, Antonio. The Three Great Sultans of al-Dawla al-Isma'iliyya and the Patronage of the Alhambra. Islamic Art, vol. 8, 1995.

Collins, Roger. Caliphs and Kings: Spain, 796–1031. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Navarro, Julio. Mudéjar Architecture. Trans. Museum With No Frontiers, 2015.

Untours Travel Blog. Andalusia’s Architecture: A Reflection of Cultural Confluence. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Thank you! Never heard of the Mudehar art-style. Love its universality in religious architecture. I know of Dona Grazia Nasi, considered the first female banker-businesswoman, who played cat and mouse with Kings of England France wanting to take her captive to pay for wars. Eventually she was invited to the court of the Ottaman Empire—which provided a haven for talent—no matter faith sex or country of origin. Art styles merged as did architecture. A really enlightened despot.