In the decades following Japan’s defeat in 1945, rapid economic growth and pervasive Western influence reshaped the nation’s social fabric, imposing new pressures toward conformity even as material prosperity soared. In reaction, Japanese youth forged covert modes of resistance, among them the phenomenon of kawaii, “cute”, which first appeared in teenage handwriting and later blossomed into a mass‐market aesthetic embodied by icons like Sanrio’s Hello Kitty (Yano 5–7). While seemingly benign, these miniature, anthropomorphic figures offered young people, especially women, a means of asserting individuality within rigid corporate and educational hierarchies (Yano 18). Concurrently, “otaku” subcultures coalesced around obsessive fandoms for manga, anime, and idols, providing alternative networks of belonging outside mainstream career or marital trajectories (Galbraith 22–25). It was into this ambivalent milieu, where innocence and obsession intermingled, that Yoshitomo Nara emerged, wielding childlike imagery as a vehicle for critique.

Nara’s artistic formation bridged East and West. After completing his BFA at Aichi Prefectural University of Arts (1982–86), he studied under Gerhard Richter and Norbert Klassen at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (1988–93), absorbing European avant‐garde traditions and punk rock’s do‐it‐yourself ethos (Calza 14; Holzwarth 38). He has recounted practicing Ramones songs in his Düsseldorf loft, an early testament to the fusion of Japanese pop culture and Western rebellion that would define his work (Holzwarth 38). Returning to Tokyo in the mid‐1990s, Nara joined Takashi Murakami’s Superflat movement, which collapsed distinctions between high and low culture and embraced two‐dimensional, manga‐inspired surfaces as a critique of consumer society (Murakami 81–83).

Although Nara’s paintings appear formally simple, with oversized heads, pared‐down limbs, and pastel backgrounds, their materiality reveals careful craft. He typically applies acrylic washes to unprimed cotton canvas, allowing pigment to seep through and create ephemeral, sketch‐like effects (Calza 56). In Sleepless Night (1999), for example, a translucent wash renders the pale child figure almost ghostly, as if at any moment it might dissolve into the raw fabric beneath (Calza 78). In subsequent sculptural works, ceramic heads and cast‐bronze figures, he translates these flattened icons into three dimensions, inviting tactile engagement and underscoring the corporeal presence of his characters (Holzwarth 102).

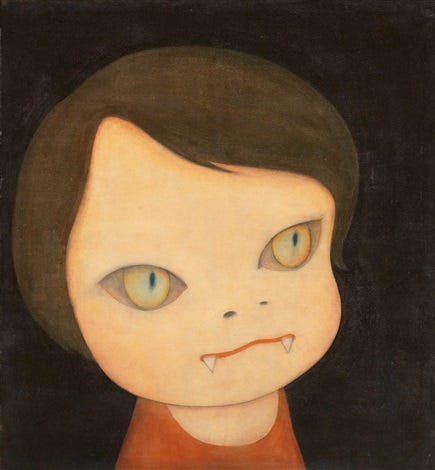

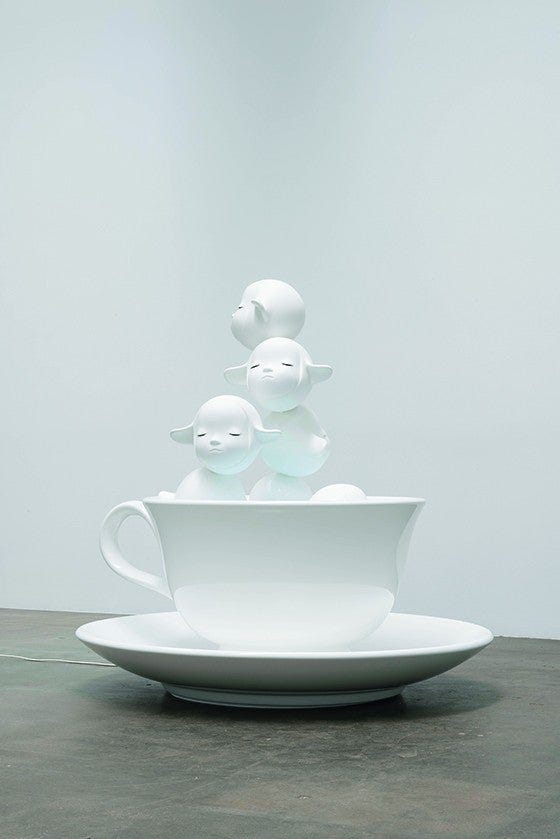

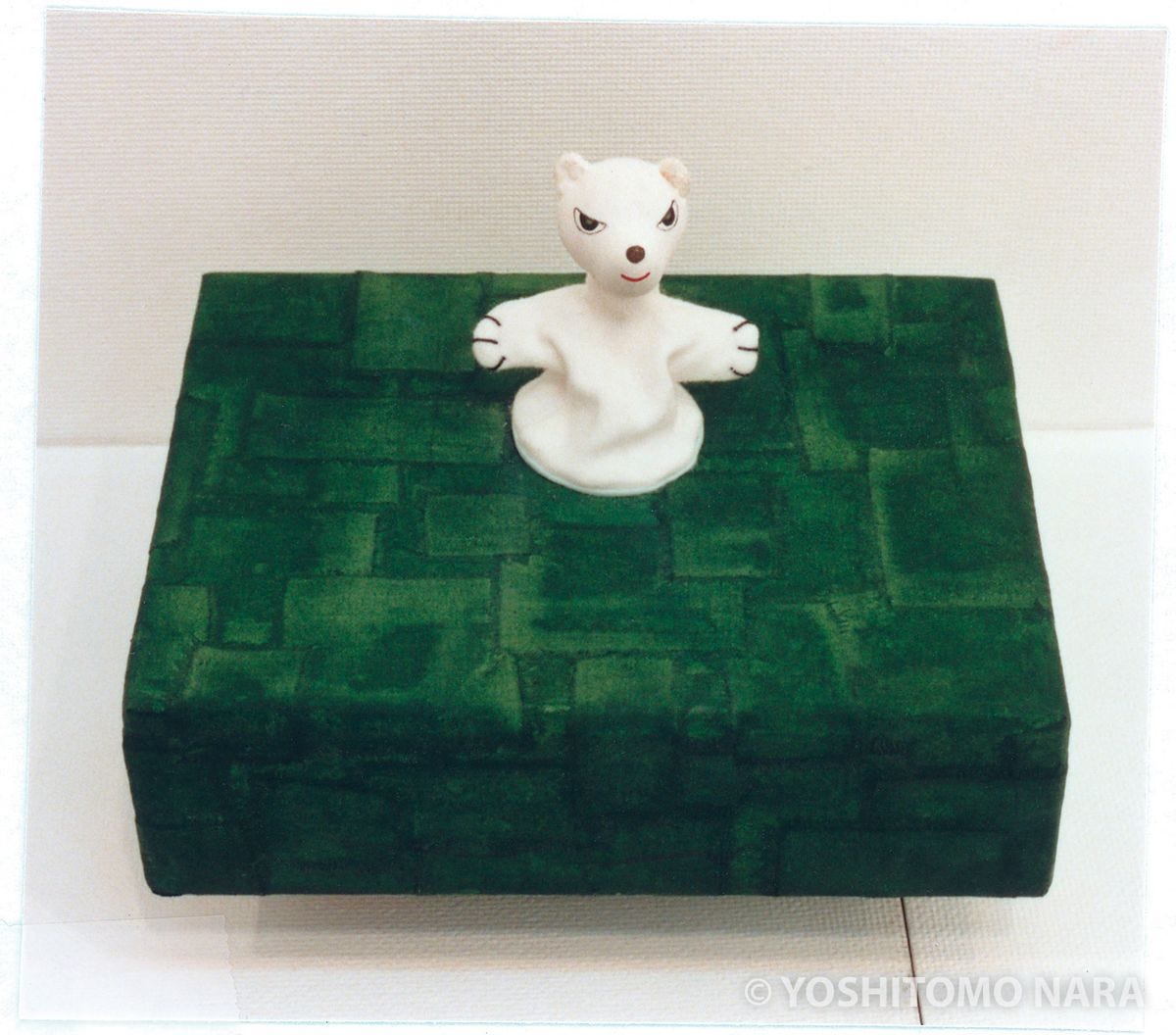

Central to Nara’s practice is the juxtaposition of childlike vulnerability with weapons of menace. In Knife Behind Back (2000), housed at MoMA, a rosy‐cheeked girl in a pink dress conceals a gleaming blade behind her back; the cotton‐white background heightening the tension between innocence and threat (Nara) . In Fountain of Life (2001/2014), Yoshitomo Nara presents a monumental sculpture featuring a teacup brimming with stacked, weeping childlike heads, their tears forming a perpetual stream. While the title nods to Marcel Duchamp’s provocative Fountain (1917), Nara replaces Duchamp’s ironic detachment with emotional vulnerability, transforming the nurturing act of tears into a symbol of collective sorrow and resilience (Calza 102; LACMA). In Polar Bear in the Green Grass (1996), a stout cub stands in steel-toed boots, serving as a pun on industrial extraction that replaces the typical knife motif with an icon of globalization (Holzwarth 88). This work reflects Yoshitomo Nara’s characteristic blend of innocence and critique, using childlike figures to comment on broader societal issues. These images realize what Precious Adesina terms the “dark side of Japanese ‘cuteness’”; the recognition that innocence can mask anger and fear (Adesina).

Gender and identity further complicate Nara’s aesthetic. Although his figures are often gender‐ambiguous, many evoke young girls, reflecting how kawaii culture has historically shaped female self‐expression. As Christine Yano observes, cuteness offered Japanese girls a subversive tool to navigate patriarchal structures, allowing them to project both fragility and willfulness (Yano 112–15). Nara’s armed girls thus become avatars of feminized resistance: small in stature yet defiantly ready to defend their personal boundaries.

Beneath these playful surfaces lies an undercurrent of national trauma. Hiroki Azuma’s theory of “database animals” describes postwar Japanese citizens as emotionally detached consumers of media, shaped by the atomic bombings and subsequent U.S. occupation (Azuma 67–69). Nara’s staring children, doll‐like yet alert, embody this paradox of hyper‐visibility and emotional numbness. Scholars also link the oversized heads and empty backgrounds to the looming specter of propaganda imagery and urban alienation in post‐1945 Japan (Murakami 94; Adesina).

Nara’s ascent into the global art world began with Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool at MoMA in 2009, where Klaus Biesenbach praised his capacity to “wield youthful iconography as a weapon of critique” (Biesenbach 23). Subsequent retrospectives, We Are the Painters at Tate Modern in 2017 and Thinker at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in 2021, traced his evolving lexicon of defiance, pairing early sculptures with new interactive installations that invited audiences to confront their own childhood memories and contemporary anxieties (Tate Modern; MFA Houston). Beyond institutional spaces, Nara’s fusion of kawaii and darkness has inspired street artists, fashion designers, and theorists worldwide, prompting renewed debates about cuteness as soft power in a globalized media landscape (Galbraith 178–80).

In forging a visual language that marries innocence with aggression, Yoshitomo Nara challenges viewers to reckon with the residual fractures of postwar Japanese society and the pressures of late capitalism. His deceptively simple figures, armed yet vulnerable, remind us that even the smallest forms can carry profound subversive potential, preserving the spirit of rebellion in the very aesthetics that mainstream culture seeks to contain.

Works Cited

Adesina, Precious. Yoshitomo Nara and the Dark Side of Japanese Cuteness. BBC Culture, 14 Aug. 2024, www.bbc.com/culture/article/20240813-yoshitomo-nara-and-the-dark-side-of-japanese-cuteness.

Azuma, Hiroki. Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. Translated by Jonathan E. Abel and Shion Kono, University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Biesenbach, Klaus. Introduction. Yoshitomo Nara: Nobody’s Fool, exhibition catalogue, The Museum of Modern Art, 2009, pp. 15–27.

Calza, Gian Carlo. Yoshitomo Nara. Phaidon, 2005.

Galbraith, Patrick W. The Otaku Encyclopedia: An Insider’s Guide to the Subculture of Cool Japan. Kodansha International, 2009.

Holzwarth, Hans W., editor. 100 Contemporary Artists A–Z. Taschen, 2009.

Murakami, Takashi. Superflat. Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, edited by Takashi Murakami, Japan Society, 2005, pp. 76–105.

Yoshitomo Nara: Thinker. Exhibition catalogue, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2021.

Nara, Yoshitomo. Knife Behind Back. 2000, acrylic on canvas. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Nara, Yoshitomo. Polar Bear. 2003, painted bronze. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. https://www.lacma.org/node/39345

Tate Modern: Yoshitomo Nara – We Are the Painters. Exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, 2017.

Yano, Christine R. Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty’s Trek across the Pacific. Duke University Press, 2013.

All I could think of is America standing guard after devastating entire cities and landscapes, air and water… honestly I don’t understand how they even would want to see or know the west. There has to be a better way.

Thankfully, Art remembers. Maybe that’s the start.

Awesome read. Thanks for the lesson.