Women’s contributions to art have historically been obscured by systemic inequalities, but their influence spans every major artistic period. As creators, women pioneered styles, techniques, and narratives. As patrons, they funded and preserved cultural legacies. As subjects, they became symbols of beauty, virtue, and power, though often constrained by the male gaze. In recent decades, feminist art movements have sought to reclaim women’s narratives and challenge the historical marginalization of female artists.

In antiquity, women often worked collaboratively with male family members in artistic production, though their contributions were rarely documented. In Ancient Egypt, women like Merit, who worked alongside her husband in sculptural workshops, demonstrated artistic skill and innovation (Crawford 12). Similarly, Greek pottery features inscriptions suggesting that women occasionally painted or decorated ceramics, though societal norms often relegated them to domestic crafts (Neils and Oakley 98).

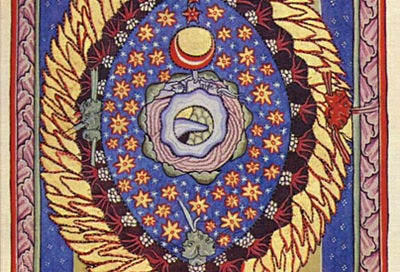

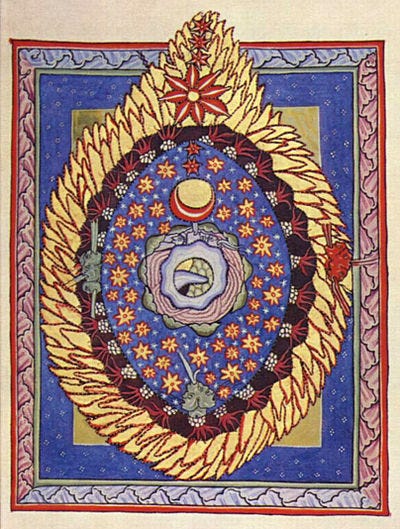

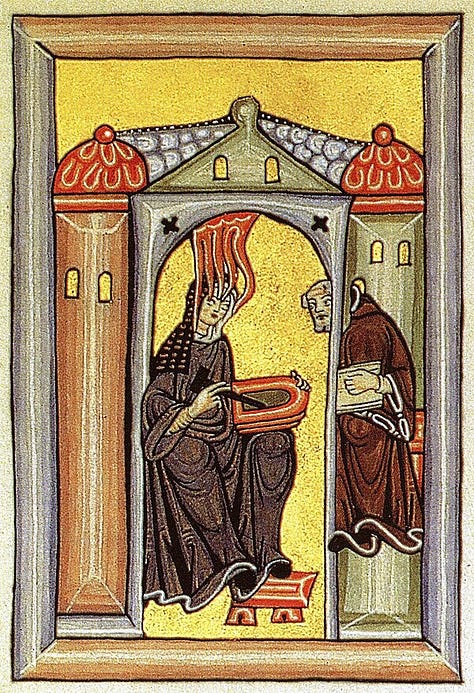

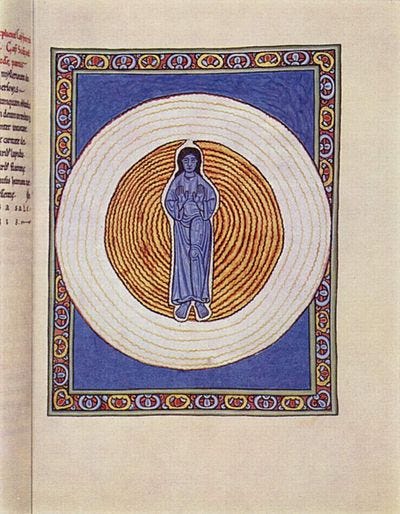

During the Middle Ages, women in monastic communities created illuminated manuscripts, textiles, and tapestries. These works combined religious devotion with artistic expression. Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th-century abbess and polymath, stands out for her illuminated visions in works like Scivias, which married theology and artistry (Flanagan 165). Additionally, nuns such as the artists of the Bayeux Tapestry produced monumental works that chronicled historical events, blending narrative with intricate design (Crawford 34).

The Renaissance brought increased recognition for individual artists, but women faced significant barriers to formal training. Sofonisba Anguissola, one of the first women to gain international fame, was praised by Michelangelo for her self-portraits and group compositions, such as The Chess Game, which depicted her family in a moment of intimacy and intellect (Garrard 56).

Artemisia Gentileschi, a Baroque painter, is celebrated for her dynamic and emotionally charged works like Judith Slaying Holofernes, which confront themes of violence, justice, and resilience. Her career, shaped by her personal experiences and determination, challenged the male-dominated art world (Garrard 89). Artemisia’s letters reveal her struggle to secure commissions and navigate patronage systems, offering insight into the professional challenges faced by women artists of her time (Bissell 214).

The Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution saw the emergence of more women artists, particularly in portraiture and genre painting. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, court painter to Marie Antoinette, exemplified grace and technical mastery. Her self-portraits, such as Self-Portrait with Her Daughter, emphasized maternal affection and feminine elegance while asserting her professional authority (Nochlin 46).

In the 19th century, women like Rosa Bonheur achieved fame for their unconventional approaches. Bonheur’s large-scale animal paintings, such as The Horse Fair, defied expectations of what women could or should paint. To gain access to the subjects she painted, Bonheur obtained a special permit to wear men’s clothing, a testament to her commitment to her craft and her defiance of societal norms (Klassen 211).

Throughout history, women patrons have significantly influenced the art world. During the Renaissance, Isabella d’Este, Marchesa of Mantua, was a pivotal figure in promoting the arts. She commissioned works from masters such as Leonardo da Vinci, Titian, and Andrea Mantegna. Her studiolo, or private study, became a showcase for Renaissance art and innovation, setting a precedent for female patronage (McAndrew 15).

In the modern era, women like Peggy Guggenheim reshaped the art world through their support of avant-garde movements. Guggenheim’s gallery, Art of This Century, became a hub for emerging artists, including Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Her personal collection, now housed in the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, remains one of the most important repositories of modern art (McAndrew 37).

Women patrons also played a crucial role in preserving and institutionalizing art. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney founded the Whitney Museum of American Art, championing contemporary American artists at a time when European art dominated the scene (Smith 72).

Women’s representation as subjects in art often mirrored societal attitudes toward gender. In classical art, women were idealized as symbols of beauty, fertility, or virtue. For example, Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos became the standard for depicting feminine beauty in the ancient world (Pollock 29).

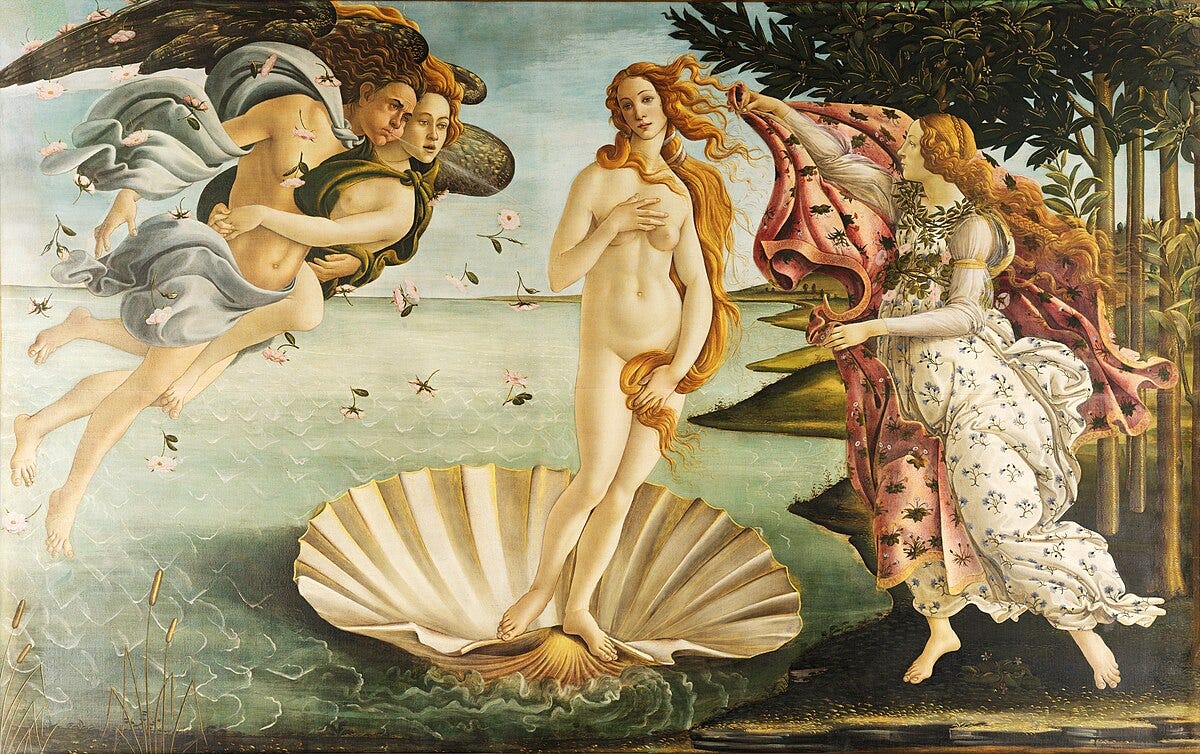

During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, women were frequently portrayed as allegorical figures, such as Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. However, these representations often confined women to roles defined by male perspectives. Feminist art historians, such as Griselda Pollock, argue that these depictions reinforced patriarchal ideals while simultaneously offering insights into cultural values (Pollock 55).

The feminist art movements of the 20th century sought to address historical inequities in the art world. Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, a large-scale installation featuring place settings for 39 iconic women, celebrated women’s contributions to history and art. This work challenged traditional art forms by incorporating ceramics, textiles, and other “domestic” materials historically associated with women (Phelan 72).

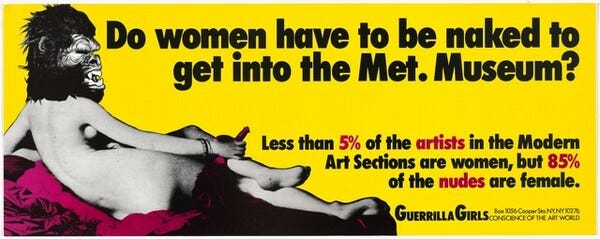

The Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous collective of feminist artists, highlighted gender and racial disparities in the art world through provocative posters and public interventions. Their 1989 poster, Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum?, critiqued the underrepresentation of women artists in major museums while emphasizing the overrepresentation of female nudes as subjects (Phelan 84).

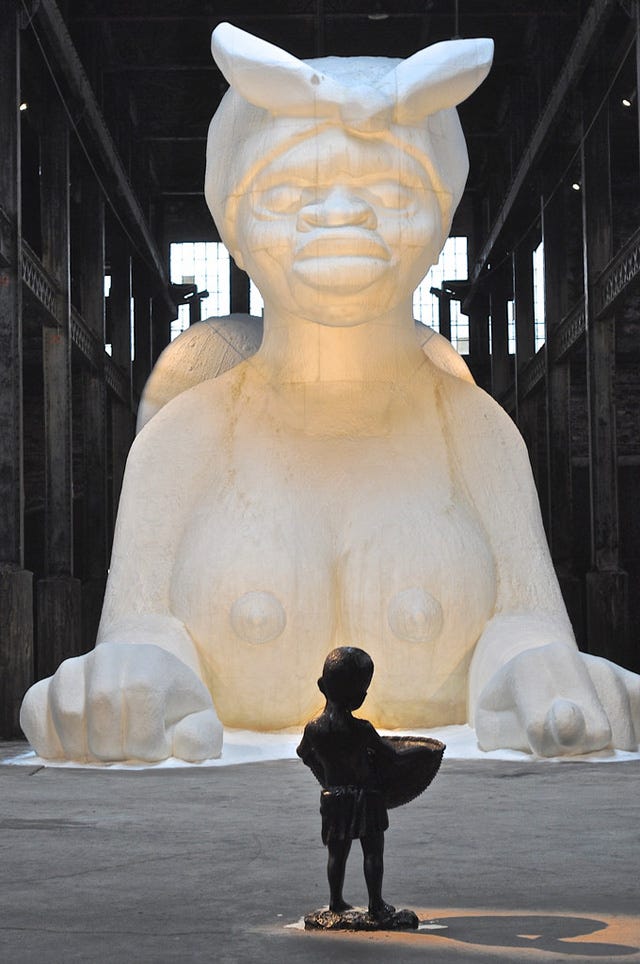

In contemporary art, women continue to innovate and push boundaries. Yayoi Kusama’s immersive installations, such as Infinity Mirror Rooms, explore themes of repetition, identity, and the cosmos. Kara Walker’s silhouette works, such as A Subtlety, interrogate the histories of slavery and systemic racism, challenging viewers to confront uncomfortable truths (Smith 67).

However, despite these achievements, gender disparities persist. Women artists account for only a fraction of solo exhibitions at major institutions, and their works are undervalued in comparison to their male counterparts at auctions (Smith 72). Efforts to address these disparities, such as the inclusion of more women artists in museum collections and art history curricula, are crucial to achieving equity.

Women have played indispensable roles in the history of art as creators, patrons, subjects, and advocates. Their contributions have shaped artistic traditions while challenging societal norms. By recognizing and celebrating these achievements, we can foster a more inclusive understanding of art history and create a future where all artists are valued equally.

References:

Bissell, R. Ward. Artemisia Gentileschi and the Authority of Art: Critical Reading and Catalogue Raisonné. Pennsylvania State UP, 1999.

Crawford, Katherine. Women and Art in the Middle Ages. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Flanagan, Sabina. Hildegard of Bingen: A Visionary Life. Routledge, 1998.

Garrard, Mary D. Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art. Princeton UP, 1989.

Klassen, Patricia. Rosa Bonheur: A Life. University of California Press, 1989.

McAndrew, Clare. The Art Market 2020: Women Artists in Focus. Art Basel and UBS, 2020.

Nochlin, Linda. Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? ArtNews, 1971.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity, and Histories of Art. Routledge, 1988.

Phelan, Peggy. Art and Feminism. Phaidon, 2001.

Smith, Rachel. Women in Art: Representation and Recognition. Journal of Contemporary Art, 2014.