Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) is one of the most celebrated artists of all time, yet his life was marked by profound struggles with mental illness, addiction, and ultimately, suicide. His paintings, characterized by expressive brushstrokes and vibrant colors, offer a unique window into the psyche of a man grappling with severe inner turmoil. Van Gogh’s struggles with chronic mental health conditions, alcoholism, and his tragic suicide at the age of 37 raise significant questions about the relationship between creativity and suffering.

Born in Zundert, Netherlands, Vincent van Gogh came from a religious family, and his father was a minister. Initially, Vincent pursued a career in ministry but eventually turned to art in 1880, at the age of 27, after spending time working as an art dealer and traveling. He was largely self-taught, though he did receive some instruction in art from his cousin Anton Mauve, a member of the Hague School. Van Gogh's early work is often characterized by dark, somber tones, as seen in paintings like The Potato Eaters (1885), a depiction of rural laborers that reflects his concern with the harsh conditions of peasant life (Lubin, 1972).

It was during his time in Paris, however, where he lived with his brother Theo from 1886 to 1888, that van Gogh’s style underwent a significant transformation. Exposed to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, as well as the works of Japanese printmakers, his palette brightened, and his brushstrokes became more dynamic. His works began to explore the emotional and psychological depth of his subjects, setting the stage for the masterpieces of his later career.

Van Gogh's mental health issues are well-documented, though the exact nature of his condition remains the subject of much debate. He is known to have suffered from severe bouts of depression, psychotic episodes, and extreme anxiety throughout his life, conditions that today might be classified as bipolar disorder, temporal lobe epilepsy, or borderline personality disorder (Blumer, 2002). His notorious act of self-mutilation in 1888, when he cut off part of his left ear following a heated argument with fellow artist Paul Gauguin, has become emblematic of his troubled mental state.

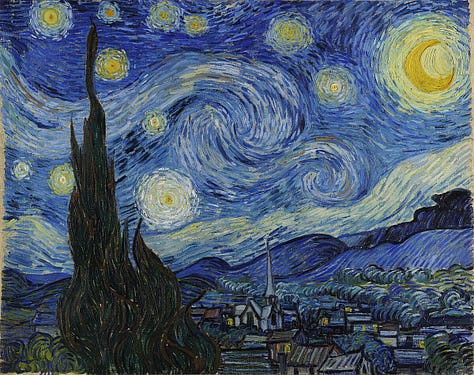

Chronic mental pain pervaded van Gogh’s life, influencing both his personal relationships and his work. His stay in the psychiatric asylum at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in 1889 resulted in some of his most famous works, such as The Starry Night and Wheatfield with Cypresses (Lubin, 1972). These paintings are characterized by swirling, almost hallucinatory imagery that reflects the intensity of his mental struggles. For van Gogh, painting served as both an outlet for his emotional suffering and a way to communicate his inner turmoil to the outside world.

Van Gogh’s addiction to alcohol, particularly absinthe, is another crucial aspect of his life. Absinthe, a potent, green-colored spirit popular in the late 19th century, was known for its strong effects and had a reputation for causing hallucinations and mental instability when consumed in excess. Van Gogh’s frequent consumption of alcohol—often in combination with his underlying mental health issues—likely exacerbated his erratic behavior and contributed to his deteriorating mental state (Sweetman, 1990).

Although absinthe is often romanticized in connection with artists of the period, such as Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, its darker side cannot be overlooked. Chronic alcoholism likely intensified van Gogh’s depressive episodes and impaired his cognitive function. His reliance on alcohol as a form of self-medication also underscores the lack of adequate mental health treatment during this period, as well as the pervasive stigma surrounding mental illness, which prevented many from seeking help (Blumer, 2002).

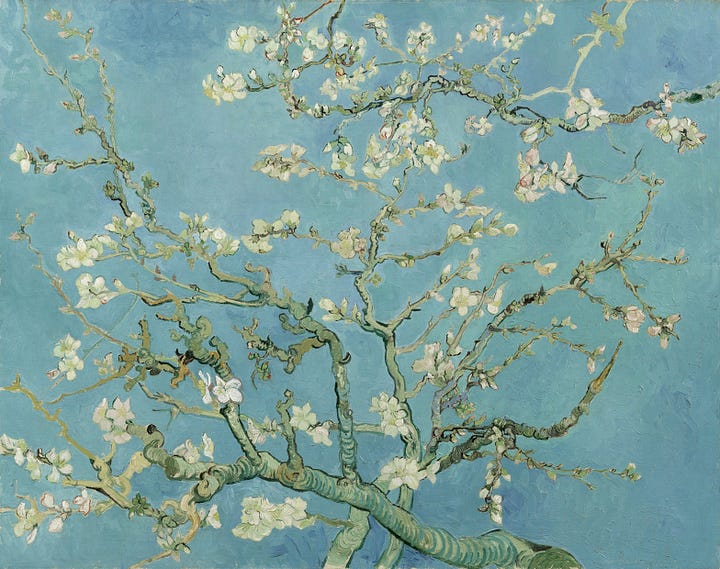

Despite his struggles with mental health and addiction, van Gogh’s artistic output during his final years was remarkably prolific. During his time in the asylum, he produced more than 150 paintings, including some of his most iconic works. The vibrant colors and emotive brushstrokes of his paintings from this period—such as Irises (1889) and Almond Blossoms (1890)—suggest an artist desperately seeking solace and meaning in nature. However, these works also exhibit an underlying sense of unease and instability, which mirrors the turbulent state of his mind.

Van Gogh's close relationship with his brother Theo, an art dealer who supported him financially and emotionally, is well-documented in the extensive letters they exchanged. These letters reveal van Gogh’s deep awareness of his own mental condition and the toll it took on his ability to work. His feelings of isolation and despair are palpable in his writings, where he frequently expressed fear of his own mental collapse and his frustration with his inability to maintain stability (Lubin, 1972).

On July 27, 1890, Vincent van Gogh shot himself in the chest in a wheat field in Auvers-sur-Oise, France. He succumbed to his wounds two days later, at the age of 37. His suicide marked the culmination of years of chronic mental pain and emotional instability, further compounded by his struggles with addiction. His death cemented his legacy as the archetypal “tortured artist,” whose work is inextricably linked to his personal suffering (Sweetman, 1990).

In the years following his death, van Gogh’s reputation grew exponentially, and today he is regarded as one of the most significant figures in Western art. His work has come to symbolize the intersection of creativity and madness, and his life story serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of mental health in the lives of creative individuals. Moreover, van Gogh’s struggles with addiction and chronic pain highlight the ways in which personal suffering can shape artistic expression, leading to some of the most emotionally resonant works in art history (Blumer, 2002).

Vincent van Gogh’s life and work illustrate the profound impact that mental health, addiction, and chronic pain can have on an individual’s artistic practice. While his struggles with these issues contributed to his tragic end, they also fueled his creative genius, resulting in some of the most celebrated paintings in the history of Western art. His legacy serves as a testament to the complexity of the human condition, where creativity and suffering are often intertwined in ways that challenge and enrich our understanding of both.

References

Blumer, D. (2002). "The Illness of Vincent van Gogh." American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(4), 519-526.

Lubin, A. (1972). Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Sweetman, D. (1990). The Love of Many Things: A Life of Vincent van Gogh. Simon & Schuster.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders. This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK(8255). In a crisis, call or text 988 (24/7).

Brilliant. Tragic. Thank you.