Dawoud Bey (b. 1953) stands as one of America’s most influential photographers, whose work interrogates and redefines the visual narrative of African American communities. His practice, which spans from the intimate street portraits of “Harlem, U.S.A.” to ambitious historical projects such as The Birmingham Project and Night Coming Tenderly, Black, challenges the dominant frameworks of representation and historical memory.

Bey’s early life in Queens and his exposure to groundbreaking exhibitions such as “Harlem on My Mind” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art were formative experiences that ignited his passion for photography. Witnessing a museum display that showcased ordinary African Americans, a rarity at the time, provided Bey with his first encounter with representation in fine art (The HistoryMakers). This encounter spurred his determination to document the everyday life of Black communities from a perspective rooted in insider knowledge.

Pursuing formal training, Bey earned a BFA from Empire State College and later an MFA from Yale University. His academic journey coincided with the rise of alternative art spaces in New York City during the 1970s, where emerging Black artists found platforms outside mainstream institutions. Bey’s early series, “Harlem, U.S.A.” (1975–1979), emerged during this vibrant period. The work not only documented the dynamic street culture of Harlem but also reflected the complex identity politics of the era. By challenging the conventional visual narratives of Black subjects, Bey laid the groundwork for an ongoing dialogue between personal identity, communal memory, and institutional representation (Wikipedia; The HistoryMakers).

At the heart of Bey’s practice is a commitment to collaboration and reciprocity with his subjects. Rejecting the detached gaze traditionally associated with documentary photography, Bey employs methods that invite his subjects to engage with their own representation. His innovative use of large-format cameras and Polaroid Type 55 film exemplifies this approach. The dual production of an immediate positive print and a high-quality negative creates a tangible exchange, a gesture in which the sitter receives an instant memento of their image. This method not only reinforces the subject’s agency but also disrupts the typical power dynamics inherent in portraiture (Sean Kelly Gallery).

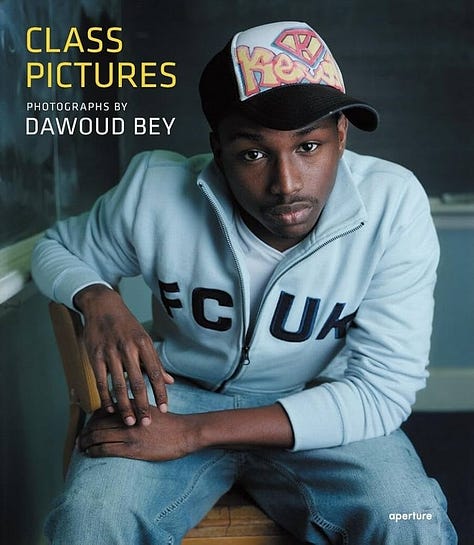

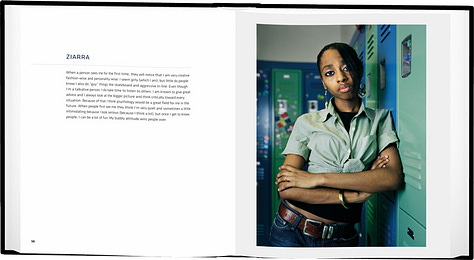

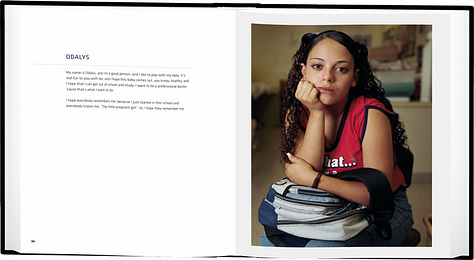

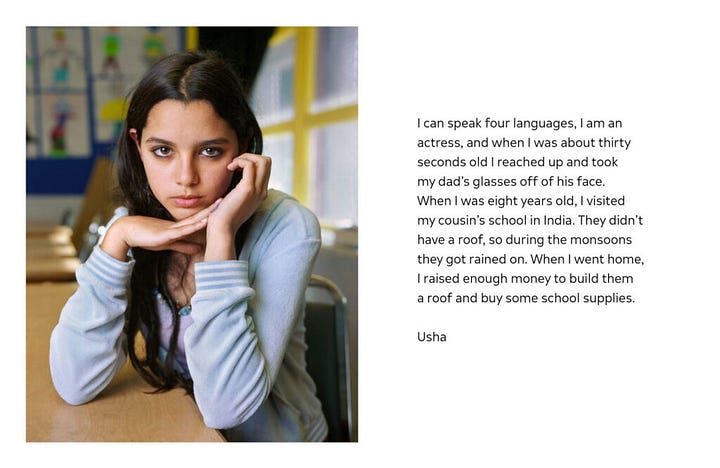

Bey’s work in projects like Class Pictures illustrates how he extends the dialogue beyond the frame. By incorporating personal statements from his young subjects alongside their portraits, he constructs a multifaceted narrative that bridges the gap between image and identity. This practice challenges the “view from above” common to traditional documentation, insisting instead on a shared experience in which both photographer and subject co-construct meaning. Through these collaborative practices, Bey transforms photography into a process of communal storytelling and self-determination.

Bey’s body of work is marked by a series of landmark projects that address both contemporary and historical dimensions of African American experience. In “Harlem, U.S.A.,” Bey captured the energy and individuality of Harlem residents during a period of profound cultural change. The series is celebrated for its ability to render the everyday as extraordinary, placing the individual at the center of a broader historical continuum.

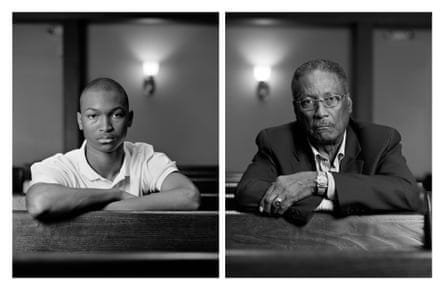

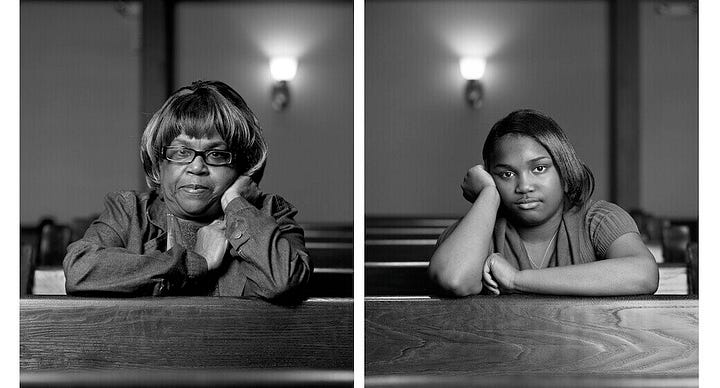

His later projects reveal a deepening historical consciousness. The Birmingham Project (2012) commemorates the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church by pairing portraits of contemporary African Americans with images symbolizing the ages the victims would have attained had they survived. This diptych format creates a poignant visual dialogue between past loss and present resilience, inviting viewers to reflect on the long shadow cast by racial violence (High Museum of Art).

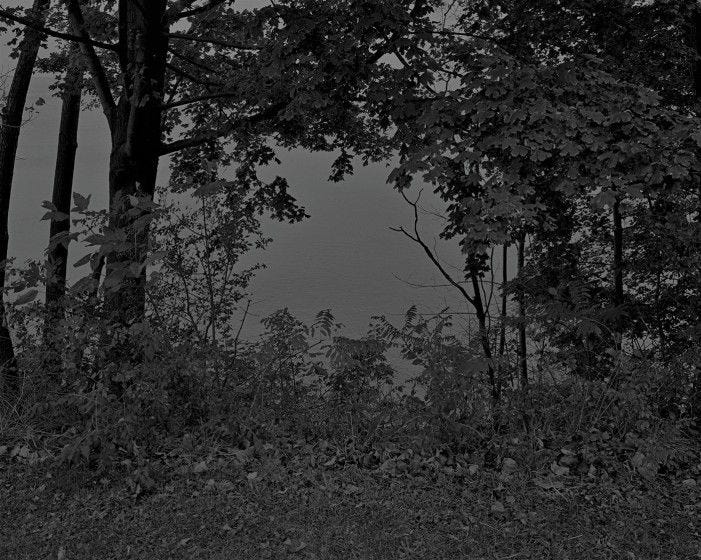

Similarly, Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017) marks Bey’s foray into landscape photography with a historical dimension. In this series, he reimagines the path of the Underground Railroad through stark, monochromatic landscapes. The work is not a literal record but a meditative evocation of the emotional and physical journey toward freedom. By rendering these spaces in deep tones and emphasizing the materiality of the landscape, Bey underscores the persistence of memory and trauma in the American landscape (SFMOMA).

Each project is a careful negotiation between form and content. Bey’s approach to historical engagement is not one of reenactment but of reinterpretation—transforming historical data into an emotional and aesthetic experience that bridges the gap between personal memory and collective history.

Bey’s work has been widely recognized by major institutions, and his exhibitions have significantly influenced the discourse on African American art. Institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, MoMA, and the High Museum of Art have hosted retrospectives and surveys of his work, affirming his status as a critical figure in contemporary photography. His collaborations with these institutions have not only elevated his profile but have also contributed to a broader revaluation of Black art within the mainstream canon.

The Studio Museum in Harlem played a crucial role in Bey’s early career. By providing a platform for “Harlem, U.S.A.,” the museum enabled Bey to present his work in a space that resonated with his subject matter and his community. This commitment to engaging with local communities continues to be a hallmark of his practice. Bey has actively sought to use museum spaces as laboratories for dialogue, curating parallel exhibitions and hosting community events that invite public interaction with his work. This participatory approach transforms the museum from a static repository into a dynamic site of cultural exchange and empowerment (The HistoryMakers; Studio Museum in Harlem).

Dawoud Bey’s photography is both a visual archive and an act of resistance. Through his collaborative practices, innovative methodologies, and historical engagements, Bey has redefined what it means to document African American life. His work transcends mere representation, forging a space where memory, identity, and aesthetic form coalesce. In challenging conventional narratives, Bey not only elevates the status of Black subjects within art history but also invites viewers to partake in a collective process of remembrance and healing. His legacy lies in his ability to transform photography into an instrument of social justice, an enduring reminder that the past is never truly past but a living presence that continues to shape our collective future.

References:

Dawoud Bey. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Accessed 11 Jan. 2025.

Dawoud Bey’s Biography. The HistoryMakers, www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/dawoud-bey-40. Accessed 11 Jan. 2025.

Dawoud Bey: An American Project. High Museum of Art, www.high.org/exhibition/dawoud-bey-an-american-project/. Accessed 11 Jan. 2025.

Dawoud Bey. Sean Kelly Gallery, www.skny.com/artists/dawoud-bey. Accessed 11 Jan. 2025.

Dawoud Bey. MoMA, www.moma.org/artists/7053. Accessed 11 Jan. 2025.

There is a gentle beauty with subtlety and yet a directness— I have always loved his work. The camera is an extension of his heart. Unlike Modotti who fired it as a weapon, Bey uncovers the emotional layers with a mere glance. A gentle caress. A soft texture. We live to see a richer experience through his eyes. Compositionally, while each is a portrait or setting, to me they are all Still Lifes. He shoots as if compositing a table of richness and taste, even in his night landscapes. Whether texturally or through lighting, we are romanced.