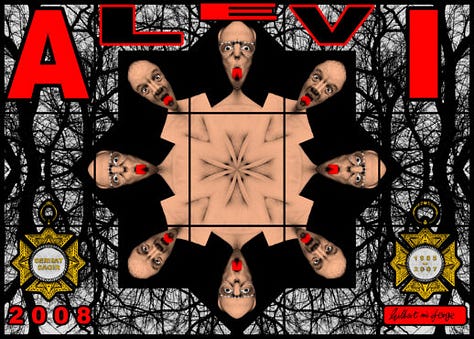

Gilbert Prousch (b. 1943, San Martin de Tor in the Italian Dolomites) and George Passmore (b. 1942, Plymouth, Devon) have been inseparable since they met in September 1967 at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London. United by a shared disillusionment with formalist sculpture, they declared themselves a single “living sculpture,” collapsing the boundary between life and art (Riding 52). As openly gay men, they confronted traditional norms of sexuality, religion, nationalism, and race, foregrounding their identities within monumental grid‐based photo‐montages and performative spectacles. Their practice, rooted in East London’s streets since 1968, refuses artistic and social marginalization, demanding visibility through bold color, profane text, and the raw presence of their own bodies.

Gilbert grew up speaking Ladin in a farming community under the final years of Fascist Italy. After art training in Wolkenstein and Hallein, he relocated to England to study sculpture at Hornsey College before enrolling at Saint Martin’s (Moderna Museet). George’s childhood in post‐war Plymouth led him through Dartington Hall and Oxford School of Art; he, too, found Saint Martin’s the place to pursue art that addressed “real life, not just studio problems” (Britannica).

Their chance meeting on September 25, 1967 began both a romantic partnership and an artistic revolution. Rejecting elitist formalism, they developed a democratic credo of Art for All, debuting public performances in 1969 while covered head‐to‐toe in metallic powders to sing “Underneath the Arches,” materializing their concept of “living sculpture” (Fuchs 61).

In 1968 they purchased a Georgian house at Fournier Street in Spitalfields, restoring it to Georgian precision yet embracing the neighborhood’s multicultural vitality. Their daily ritual, identical breakfasts, journaling, studio work, and walks through Brick Lane, underwrites the discipline behind their expansive photo‐montages (Guardian).

Donning Savile Row suits, they inverted expectations of both avant‐garde bohemia and queer subcultural codes. Registering a civil partnership in 2008, they reject reductive identity labels, insisting their work speaks universally even as it stages gay intimacy at billboard scale. Self‐described Thatcherites, they nonetheless excoriated xenophobia, religious hypocrisy, and moral censorship in series like The Fundamental Pictures and Scapegoating Pictures for London (Demos 121).

Gilbert & George’s The Singing Sculpture (1969) inaugurated their signature “living sculpture” practice by casting themselves, clad in Savile Row suits and painted head-to-toe in metallic bronze powder, as enduring art objects atop a plain wooden table while continuously singing Flanagan & Allen’s Depression-era ditty “Underneath the Arches.” The duo moved with puppet-like precision, circling mechanically, swapping a striped cane and a rubber glove, transforming performance, duration, and audience expectation into a single sculptural tableau that blurred high culture and vaudeville, permanence and ephemerality. First staged at Saint Martin’s School of Art and later presented at venues from the National Jazz and Blues Festival to the Whitechapel Art Gallery, these durational actions, sometimes lasting up to eight hours, challenged conventions of both sculpture and performance, insisting that “we don’t do performance art. We are the art” and laying the groundwork for all their subsequent grid-based “Pictures” (Fuchs 61).

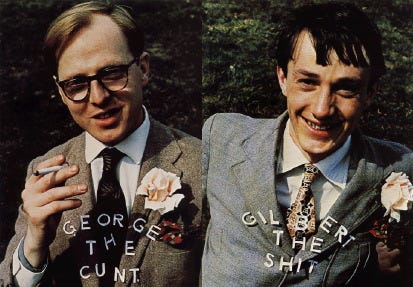

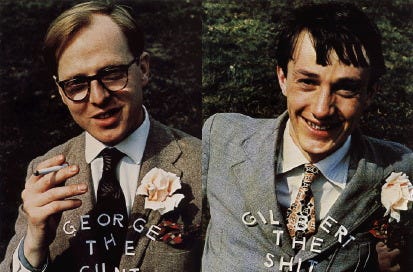

George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit (1969–70) is a provocative two-panel photographic diptych that the artists first presented as a “Magazine Sculpture” in Studio International. Dressed identically in Savile Row–style suits with boutonnières, George casually smoking and Gilbert grinning, the pair stand against a neutral backdrop while cut-out letters spelling their own epithets (“George the Cunt” and “Gilbert the Shit”) are emblazoned across their chests, pre-empting and subverting the insults they anticipated from critics. By reclaiming these profanities as self-titles, Gilbert & George collapse the boundary between art and life, asserting their bodies, and language, as the primary medium of their “living sculpture” practice. The work’s deadpan formality, cheeky humor, and confrontational language marked a decisive shift toward the duo’s lifelong credo of Art for All, insisting that high art must embrace everyday speech, taboo subjects, and the vulnerability of the artists themselves (Lodge 88).

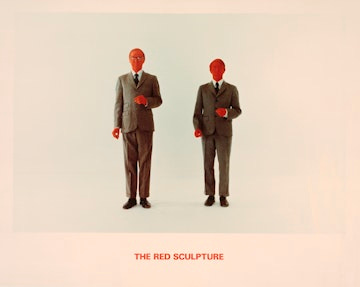

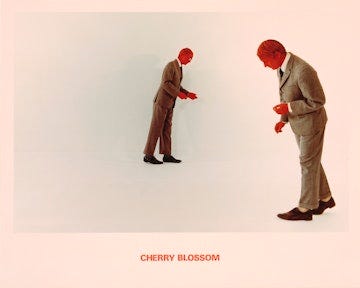

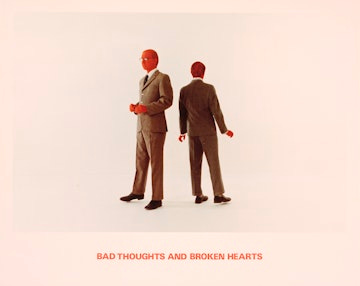

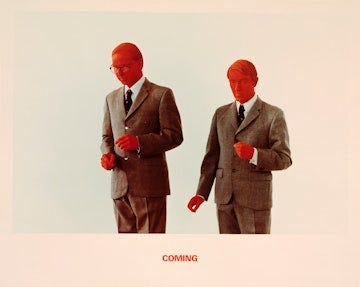

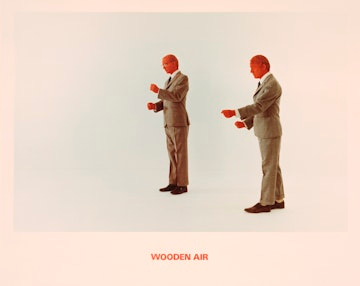

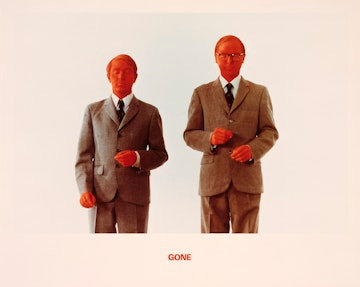

Gilbert & George’s The Red Sculpture (1975) is an artist’s book presented as a red cloth–bound volume (edition of 100) containing eleven chromogenic color prints. Signed and numbered on the title page, the work challenges traditional distinctions between object and image by treating photographic pages as sculptural panels, echoing the duo’s ongoing “living sculpture” ethos. Its design, a slipcased quarto format, underscores the artists’ commitment to Art for All: an accessible, democratic presentation of self–portraiture and text that extends their performative practice into the domain of the printed book (Bickers 117).

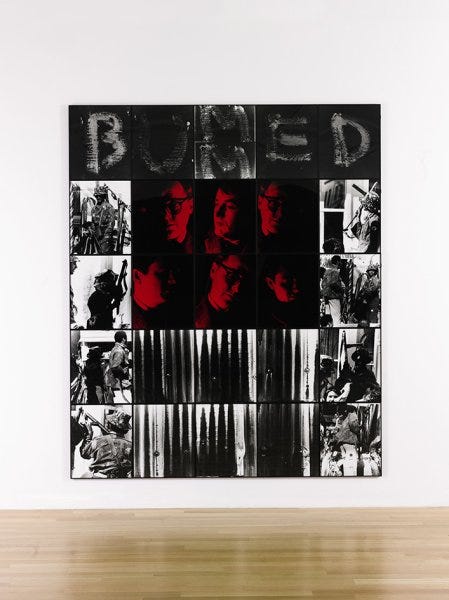

Gilbert & George’s Dirty Words Pictures (1977) is a series of 26 large-scale black-and-white photographic panels, each overlaid with a single scrawled profanity, “CUNT,” “QUEER,” “FUCK,” and the like, harvested directly from East London graffiti and urban signage. The works are printed in stark high-contrast with touches of red, presenting the words frontally as if shouted at the viewer, yet the tinted window-pane format also reveals familiar, ratty street scenes, shop fronts, alleyways, and the Thames skyline, beneath the lettering. By monumentalizing these everyday expletives, the duo forces an encounter with language and place, highlighting the social neglect and raw energy of urban life, turning graffiti from a background murmur into the very subject of their art (Muir 102).

A photographic installation by Gilbert & George comprising 28 individual gelatin-silver prints mounted in a rectilinear grid to form a single monumental work. Each panel depicts a figure, often the two artists themselves among groups of young working-class men, tinted in hyper-saturated hues of cyan, magenta, and yellow so that the overall composition appears akin to a glowing stained-glass window. Created at a moment of political tension in mid-1980s Britain, “Existers” channels the social anxieties of its era, community solidarity, alienation, and the performative nature of identity, into a unified, confrontational image. (Muir 135).

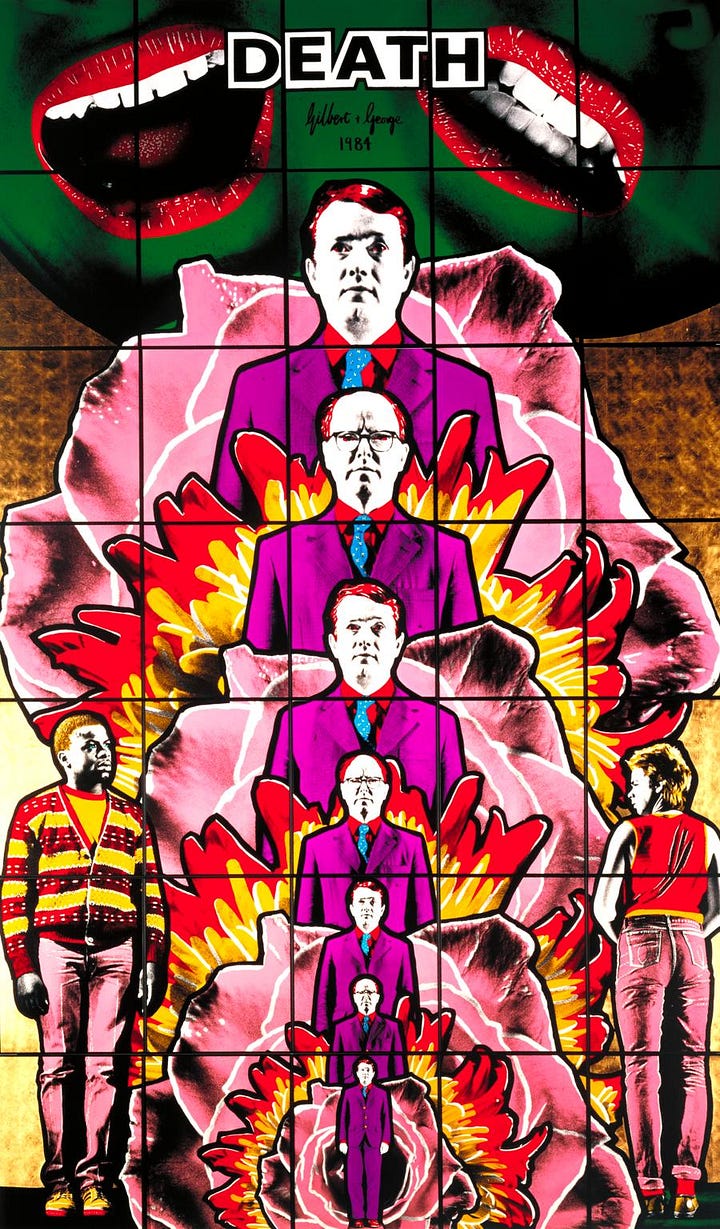

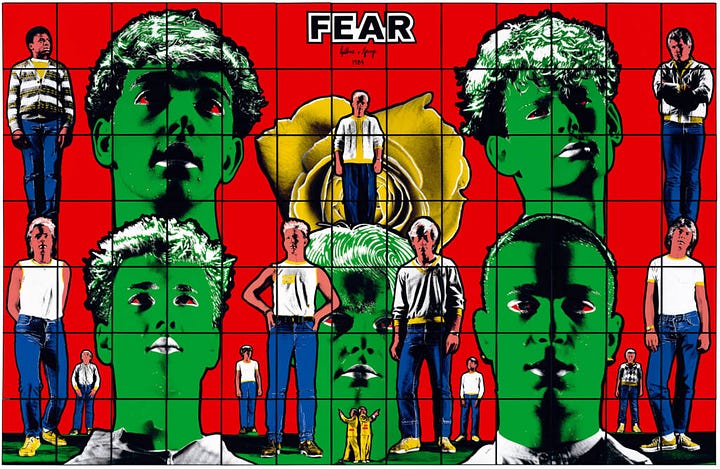

Gilbert & George’s Death Hope Life Fear… (1984) is a monumental four-panel photomontage. In this quadriptych, the artists blend saturated fields of color with emblematic imagery, young figures, natural elements, and the duo themselves, to probe what they term the “fundamentals of human existence”: the inescapable cycle of mortality (Death), aspiration (Hope), vitality (Life), and anxiety (Fear). Executed at a pivotal moment in their practice, the work’s ritualistic symmetry and bold color palette both echo and subvert religious iconography, framing modern life as a universal rite of passage that is at once cosmic and deeply personal (Riding 54).

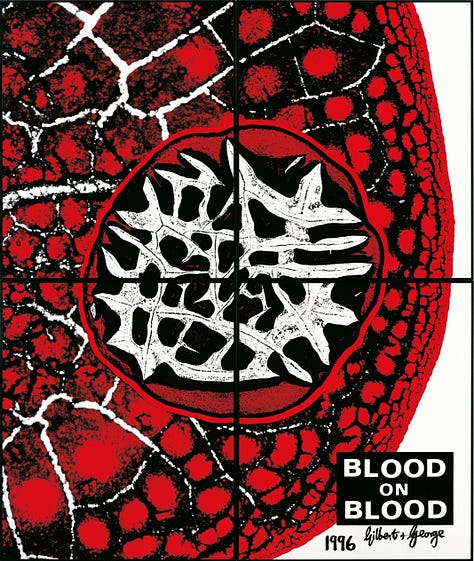

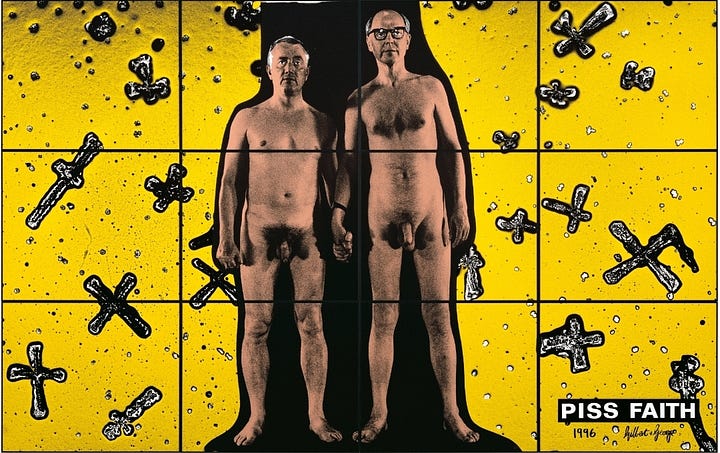

“The Fundamental Pictures” (1996–97) is a landmark series of thirty-nine large-scale photographic works by Gilbert & George, exhibited simultaneously at Lehmann Maupin and Sonnabend Galleries in New York from May 3 to June 28, 1997. Departing from their earlier grid-based montages of urban life, the duo adopted microscopic samples of bodily fluids, blood, spittle, urine, feces, and semen, as raw material, photographing and enlarging them into vibrant abstractions arranged in modernist grids. Each piece bears a provocatively literal title (e.g., Piss Guns, Blood on Blood, Spunk on Us), confronting taboos around the body, sexuality, and violence while retaining the artists’ democratic credo of “Art for All”.

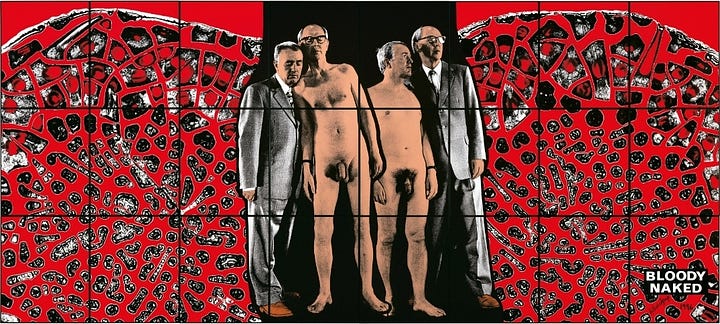

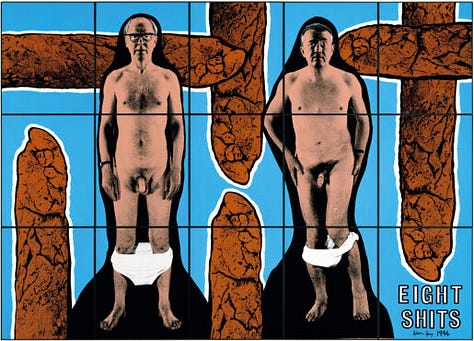

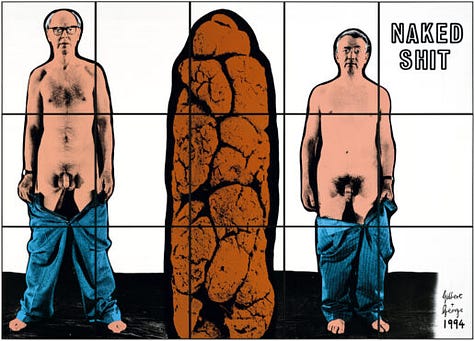

Gilbert & George’s The Naked Shit Pictures (1994–95) is a provocative series of 20 large-scale photographic works that were hung from floor to ceiling in frieze-like installations. The series juxtaposes the artists’ own naked or semi-dressed bodies with dramatically enlarged images of excrement, titles include Flying Shit, Mob Law, and Eight Shits, underscoring themes of bodily abjection and human vulnerability. Through these confrontational images, Gilbert & George dismantle societal taboos around excretion and nakedness, transforming private shame into public spectacle and reaffirming their long-standing credo of “Art for All” by demanding viewers engage with the most basic aspects of human existence (Jahn 109).

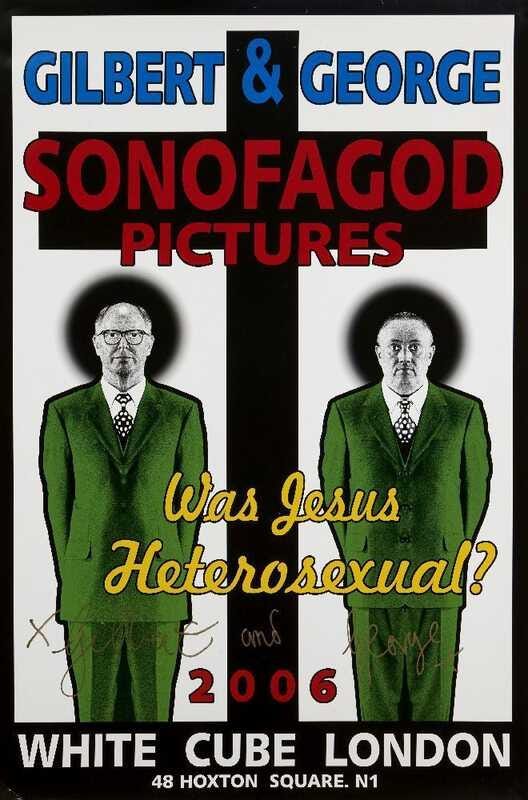

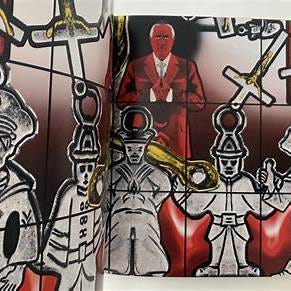

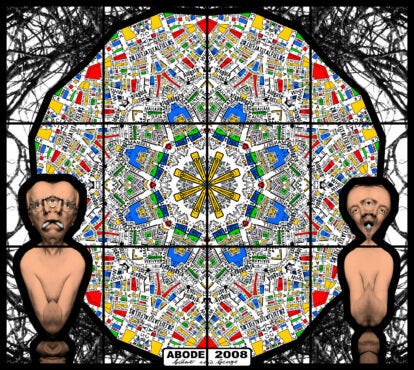

Gilbert & George’s Sonofagod Pictures: Was Jesus Heterosexual? (2005) is a landmark grid-based series of twenty chromogenic prints that meld neo-Gothic stained-glass iconography with bluntly queer, blasphemous text to critique Christian heteronormativity and institutional dogma. Each panel, arranged in rectilinear formations resembling ecclesiastical windows, features the artists themselves in iconographic poses, framed by ornate Celtic and Moorish motifs and overlaid with provocative slogans such as “WAS JESUS HETEROSEXUAL?” and “GOD LOVES FUCKING!” Rendered in sumptuous jewel-tones (crimson reds, sapphire blues, gold highlights), the works oscillate between reverence and irreverence, inviting viewers to confront the intersections of faith, sexuality, and authority within contemporary society (Smith 74).

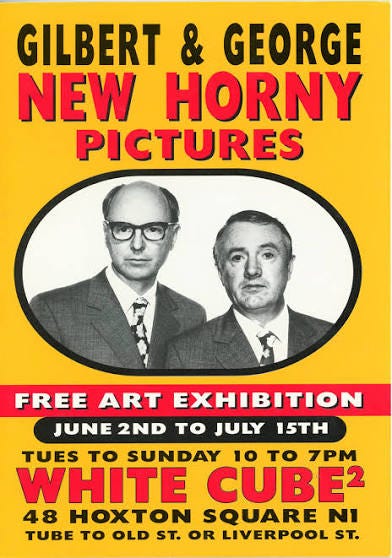

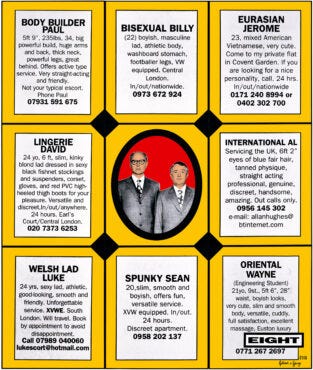

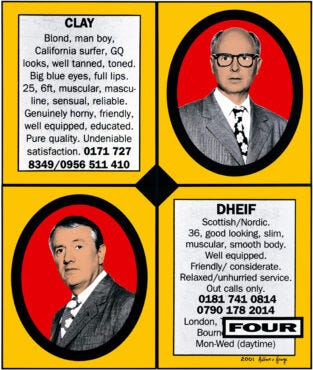

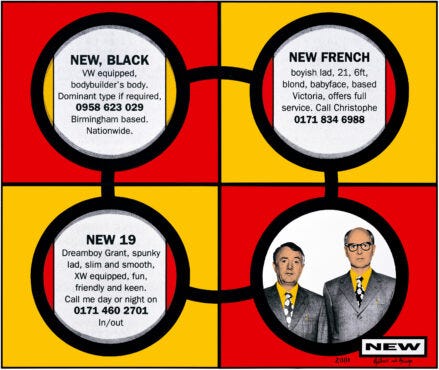

Gilbert & George’s New Horny Pictures (2001) transforms the anonymous intimacy of London’s underground gay personal ads into a monumental public spectacle. For their White Cube Hoxton Square exhibition (June 2–July 15, 2001), the duo harvested hundreds of classified listings, headlines, abbreviations (“IR,” “TOP/SUB”), phone numbers, and rephotographed them as chromogenic prints mounted in rectilinear grids up to three meters wide, the uniform columns of text glowing like neon signage and demanding viewers confront desire as both commodity and community. By stripping away faces and bodies, they preserved anonymity even as they staged a mass portrait of queer life at the turn of the millennium, blending Modernist rigor with erotic content to insist that “Art for All” encompasses the full spectrum of human longing (Riding 58).

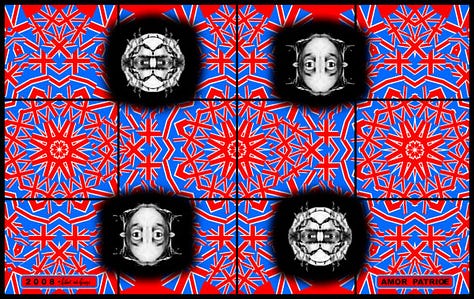

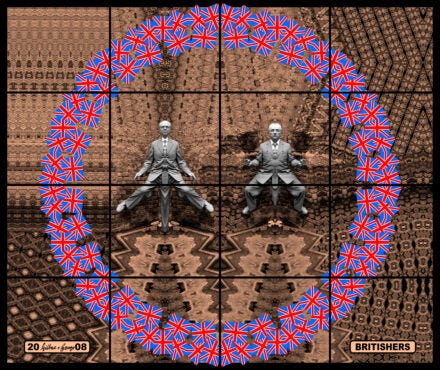

Over 150 grid panels featuring Union Jacks, military medals, and maps with the artists’ own figures, parodying nationalism and martial masculinity (Bickers 184).

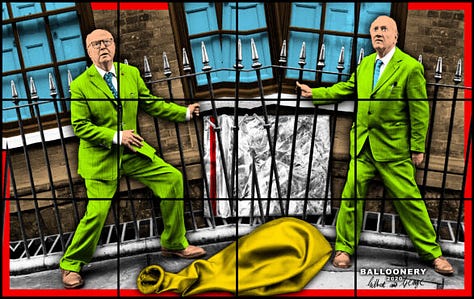

Gilbert & George’s Scapegoating Pictures for London (2013–14) is a monumental series of over fifty color photographic panels, each arranged in rectilinear grids that merge minimalist order with vivid, acid-toned spectacle. The works transform East London’s detritus, most notably discarded nitrous-oxide canisters, into metaphorical “bombs,” interspersed with the artists and local participants depicted as fractured, mask-like figures in veils, skeleton costumes, or impassive stares, symbolizing the act of communal blame. Saturated in electric blues, sickly yellows, and toxic greens, the palette amplifies a sense of urban paranoia and moral malaise, while the grid format echoes stained-glass windows, underscoring Gilbert & George’s manifesto of “Art for All” by making incisive sociopolitical critique immediately legible to any viewer. Debuting at White Cube Bermondsey in July 2014, the series holds up a mirror to London’s multicultural tensions, religion, immigration, youth culture, revealing how, in the modern metropolis, scapegoating corrodes community cohesion and targets the most vulnerable (Demos 136).

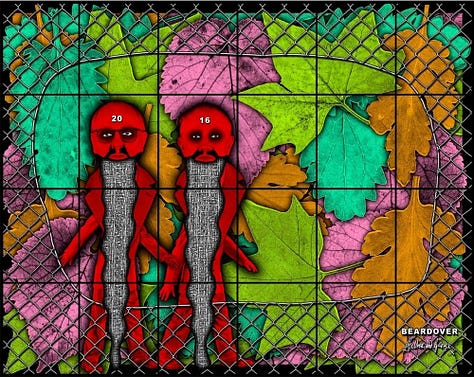

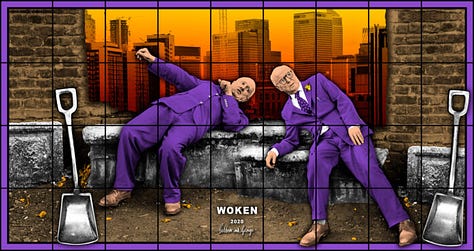

Gilbert & George’s Beard Pictures (2016) is a sprawling, multi-panel series of large-scale mixed-media photographic works in which the artists satirically appropriate male facial hair as both symbol and material to critique contemporary culture, politics, and religion. Displayed at Lehmann Maupin, New York, and later at White Cube Bermondsey, the works, titled such as BEARD CODE, VOTE BEARD, and BEARD JUNCTION, feature grotesquely exaggerated red beards superimposed upon the artists’ own faces and those of local participants, rendered in lurid, “sickly” color palettes that amplify a sense of urban paranoia and absurdity. The series deploys hundreds of panels arranged in rectilinear grids, a formal strategy that echoes their earlier “Pictures” while mobilizing text elements, words like “FUCKOSOPHY” and “BEARDFAITH”, to underscore the anti-elitist ethos of “Art for All”. By conflating the intimate act of beard growth with public spectacle, Beard Pictures reaffirms Gilbert & George’s commitment to collapsing the boundaries between art, life, and political provocation (Smith 81).

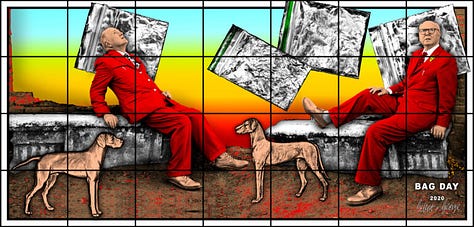

Gilbert & George’s New Normal Pictures comprises 26 large-scale digital photomontages that extend their signature grid format into the era of pandemic and political upheaval. Each panel assembles fragments of the artists’ own images, faces masked or eyes closed, alongside motifs of closed venues, distorted headlines, and urban detritus, all rendered in gleaming, hyper-saturated color to evoke the dissonance between ritualized lockdown routines and the yearning for communal life. As with their earlier “living sculptures,” the duo themselves appear within the grid, now tethered by themes of social distancing, fractured public rituals, and the uneasy recalibration of daily norms; the title New Normal Pictures thus becomes both ironic and prophetic, capturing a moment when art itself had to adapt to new forms of encounter and display (Riding 62).

For over five decades, Gilbert & George have wielded provocation as strategy, converting their bodies into sites of political confrontation. Their grid‐based iconography, profane text, and unabashed queer imagery unsettle viewers, refusing complacency and demanding reflection on nationalism, religion, censorship, and the abject body. As living sculptures, they exemplify art’s power to disturb and endure.

References:

Bickers, Patricia, editor. Gilbert & George: The Complete Pictures, 1971–2005. Tate Publishing, 2007.

Britannica. George Passmore. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2025, www.britannica.com/biography/George-Passmore. Accessed 27 Feb 2025.

Demos, T. J. The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis. Duke University Press, 2013.

Fuchs, Rudi. Gilbert & George: Major Exhibition. Tate Modern, 2007.

Gilbert & George. The Singing Sculpture (1969). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-the-singing-sculpture-l01132. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit (1970). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-george-the-cunt-and-gilbert-the-shit-l01163. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

The Red Sculpture (1974). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-the-red-sculpture-p78376. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Dirty Words Pictures (1977). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-dirty-words-p01454. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Existers (1984). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-existers-p01643. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Death Hope Life Fear.… (1984). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-death-hope-life-fear-t03473. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

The Fundamental Pictures (1996–97). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-the-fundamental-pictures-t06691. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Naked Shit Pictures (1994–95). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-naked-shit-p02404. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

The New Horny Pictures (2001). Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gilbert-george-the-new-horny-p02407. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Sonofagod Pictures: Was Jesus Heterosexual? (2005). White Cube, www.whitecube.com/exhibitions/sonofagod-pictures-was-jesus-heterosexual-2005. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

The Jack Freak Pictures (2008). White Cube, www.whitecube.com/exhibitions/jack_freak_pictures. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Scapegoating Pictures for London (2013). White Cube, www.whitecube.com/gallery-exhibitions/scapegoating-pictures-for-london. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

BEARD PICTURES (2016). White Cube, www.whitecube.com/gallery-exhibitions/the-beard-pictures-and-their-fuckosophy. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

NEW NORMAL PICTURES (2022). White Cube, www.whitecube.com/exhibitions/new_normal_pictures. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Glenstone Museum. Gilbert & George: Biography. Glenstone, 2024, www.glenstone.org/exhibitions/gilbert-and-george/. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Jahn, Wolf. The Art of Gilbert and George, or, an Aesthetic of Existence. Thames & Hudson, 1989.

Lehmann Maupin. Gilbert & George: Biography. Lehmann Maupin, 2024, www.lehmannmaupin.com/artists/gilbert-george. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Lodge, Guy. The Filthy Gospel of Gilbert & George. Art Monthly, no. 274, 2003, pp. 88–92.

Moderna Museet. Introduction: Gilbert & George. Moderna Museet, 2020, www.modernamuseet.se/en/2017/gilbert-george/. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Muir, Robin. Gilbert & George: Intimate Conversations. Phaidon Press, 1997.

Riding, Christine. Gilbert & George: Performing the Sacred and the Profane. Art History, vol. 39, no. 1, 2016, pp. 49–66.

Smith, Roberta. Looking for Trouble with Gilbert & George. The New York Times, 25 Mar. 2005, www.nytimes.com/2005/03/25/arts/design/looking-for-trouble-with-gilbert-george.html. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Studio International. 50 Years of Gilbert & George. Studio International, 2017, www.studiointernational.com/index.php/gilbert-george-retrospective. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Wikipedia. Gilbert & George. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilbert_%26_George. Accessed 27 Feb. 2025.

Following them over the years has been like waiting for the next in a series of books bordering both on comic while tragic because they mirror our isms of the times so blatantly.

I recall the show in ‘97 and feeling like Gilbert and George were just everywhere I turned in NYC that year.

How they have managed to use a particular method of execution to its fullest potential over and over, elevating the effect of the medium by giving it their voice in so literal a way. You can hear them in the room bantering and challenging you. I find it the most audible inaudible art ever experienced.