The Unfolding Canvas: Sculpture’s Reinvention from Greek Kouroi to Contemporary Installations

Sculpture has long stood as one of humanity’s most powerful means of expression; a dynamic art form that records cultural, technological, and philosophical change. From the disciplined grace of ancient kouroi to the innovative installations of today, sculpture continuously reinvents itself in response to evolving aesthetics, social values, and technological possibilities.

The origins of Western sculpture are rooted in ancient Greece and Rome, where artists strove to idealize the human form. During the Archaic period (c. 800–480 BCE), Greek sculptures such as the kouros and kore figures established early notions of harmony and proportion. These works emphasized geometric symmetry and an enigmatic “Archaic smile” that many scholars interpret as a symbol of eternal youth. In the Classical period (c. 480–323 BCE), the introduction of contrapposto, the technique of shifting weight to create a more natural stance, revolutionized naturalistic representation. Works like Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer) set a benchmark for anatomical precision, while the Parthenon sculptures, attributed to Phidias (447–432 BCE), combined mythological narrative with dynamic realism (Britannica, Western Sculpture – Classical, Greek, Roman). The emotive intensity characteristic of Hellenistic sculpture, as seen in pieces such as Laocoön and His Sons (c. 200 BCE), expanded the expressive possibilities of the medium. Roman sculptors, while borrowing heavily from Greek models, excelled in portraiture, as illustrated by Augustus of Prima Porta (1st century CE), where naturalistic detail and imperial symbolism merge (Britannica).

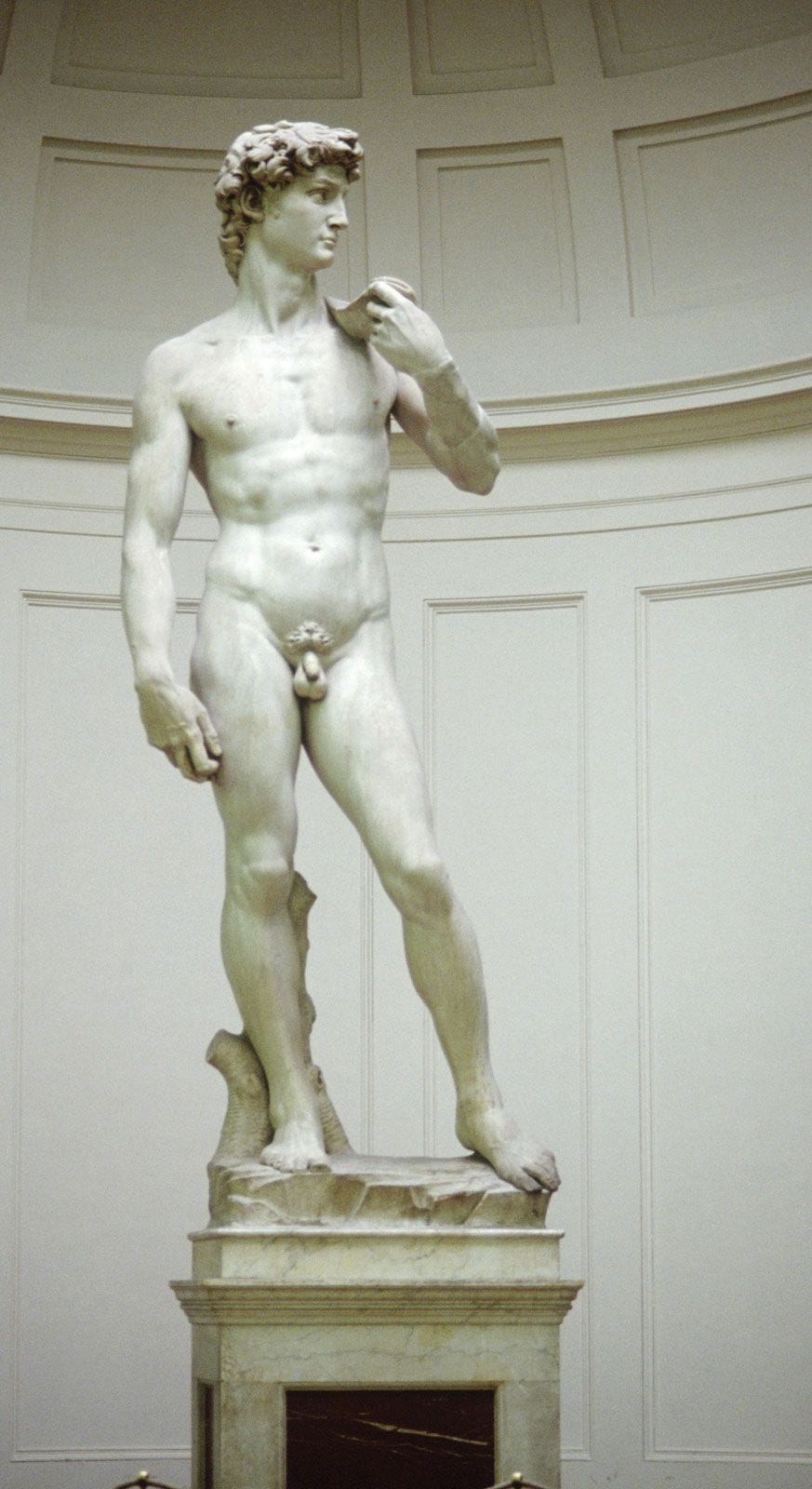

In the medieval period, the scale of sculpture shifted as religious iconography became paramount in Byzantine and Gothic art. Monumental public sculptures were largely replaced by intricate tympanums, reliefs, and ecclesiastical decorations in Gothic cathedrals. However, the Italian Renaissance (14th–16th centuries) reawakened classical ideals with a renewed focus on humanism and technical mastery. Donatello’s David (1440s), recognized as the first freestanding nude since antiquity, underscored breakthroughs in bronze casting and an emerging interest in realistic human expression. Similarly, Michelangelo’s David (1504) achieved an extraordinary fusion of anatomical precision with heroic symbolism, encapsulating Renaissance humanism at its peak (Visual Arts Cork, Sculpture History). Such innovations, including the use of preparatory wax models, would later resonate with modern artists who challenged traditional materials and methods.

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a dramatic departure from classical norms as sculptors embraced new materials and abstract forms. Edgar Degas’ Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1881) exemplifies this transformative era. Constructed with pigmented beeswax, a metal armature, authentic fabric, and even human hair, this work presents a candid depiction of everyday life. By portraying Marie van Goethem, an unidealized, working-class ballet dancer, Degas critiqued the exploitation endemic to the art world and society at large. Although early critics dismissed the piece as unconventional, its naturalistic detail and raw portrayal of human form underscored the tension between artistic expression and societal norms (Petersen and Borsch, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Cohan, The New York Times). In parallel, Auguste Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais (1889) eschewed heroic idealism for a direct portrayal of emotional struggle, and Pablo Picasso’s Guitar (1912) challenged preconceived notions of form by employing deconstruction techniques that redefined sculptural language (Visual Arts Cork, Sculpture History).

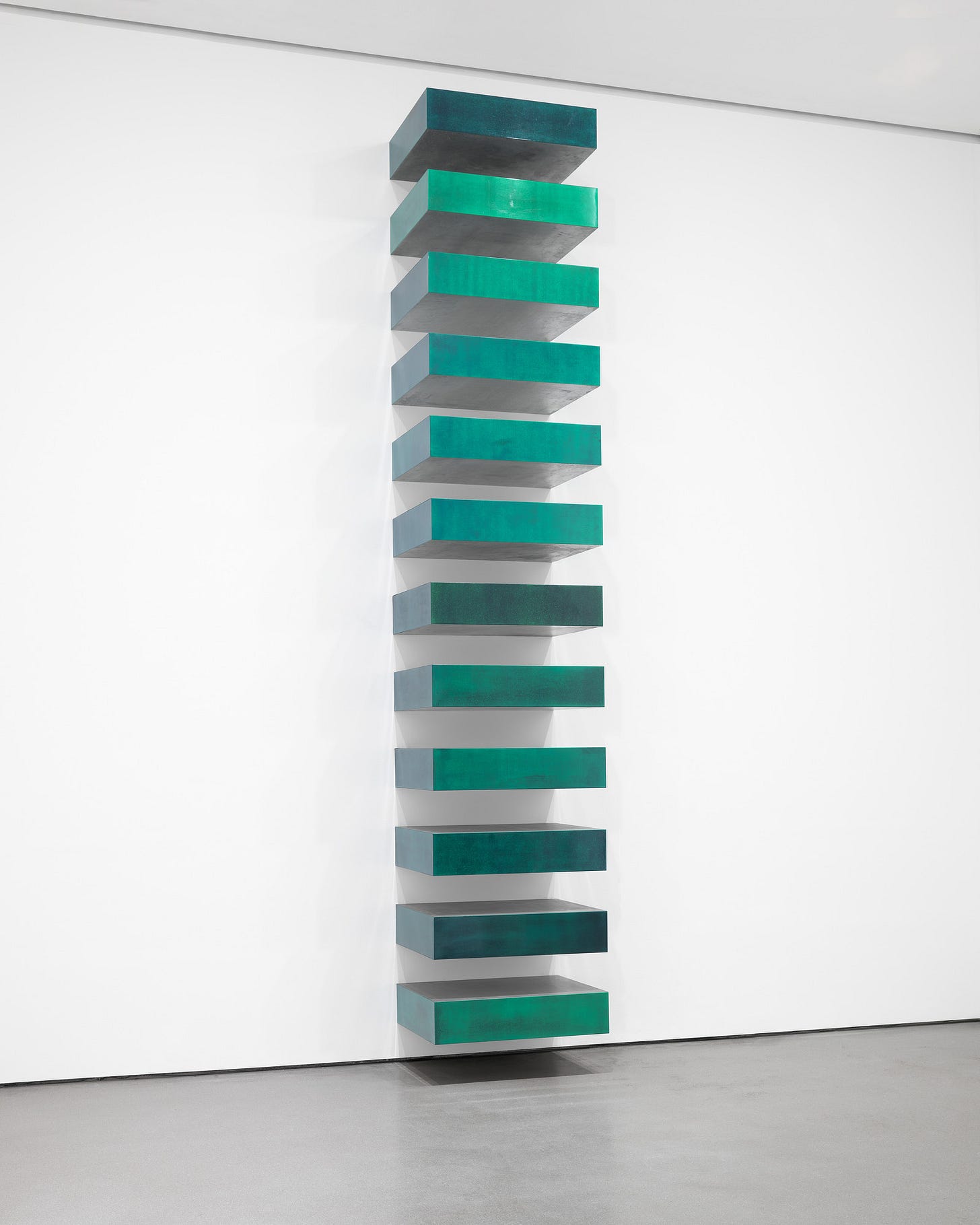

Since the 1960s, sculptural practice has further expanded its boundaries through conceptual, site-specific, and participatory projects. Minimalists like Donald Judd created geometric installations that reconfigured the perception of space, while Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), an expansive earthwork in Utah’s Great Salt Lake, illustrates the seamless integration of art and landscape (Visual Arts Cork). Contemporary artists engage with identity politics and social critique; for example, Kara Walker’s large-scale installations interrogate issues of race and power, and Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2010) employs thousands of handcrafted porcelain pieces to question notions of mass production and collectivism. The 2014 musical Little Dancer further reinterprets the narrative of Marie van Goethem, echoing modern sensibilities about art’s ability to address sociohistorical issues (Buchanan). Moreover, technological advancements such as 3D scanning, employed by institutions like the National Gallery of Art to preserve Degas’ fragile original, continue to push the boundaries of sculptural practice. Artists including Olafur Eliasson, with works like The Weather Project (2003), and Neri Oxman’s Silk Pavilion (2013) merge technology, science, and environmental design, thereby extending the experimental legacy of sculpture into the digital age.

From the marble quarries of ancient Greece to the digital laboratories of contemporary studios, sculpture has maintained an enduring ability to provoke, reflect, and transform. Early works celebrated idealized beauty and harmonious proportion, while modern and contemporary pieces invite viewers to engage with art on multisensory and intellectually challenging levels. Degas’ Little Dancer Aged Fourteen remains a seminal work; a bridge between realism and modernity that critiques societal inequities while inspiring future innovation. Overall, the evolution of sculpture is a compelling testament to the productive interplay between tradition and innovation, a process that continues to redefine the possibilities of art.

References:

Britannica. Western Sculpture – Classical, Greek, Roman. Britannica, 12 Jan. 2000, www.britannica.com/art/Western-sculpture/The-Classical-period.

Buchanan, Cathy Marie. The Painted Girls. Penguin Books, 2013.

Cohan, William D. Brass Foundry Is Closing, but Debate Over Degas’s Work Goes On. The New York Times, 5 Apr. 2016, www.nytimes.com.

Kendall, Richard. Degas and the Little Dancer. Yale University Press, 1998.

Petersen, Glenn, and Linda Borsch. The Evolution of Degas’s Little Dancer. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 8 Apr. 2021, www.metmuseum.org.

Sculpture History. Visual Arts Cork, www.visual-arts-cork.com/sculpture-history.htm.

For me, sculpture has most consistently evoked more emotion than any other art form. A few artists and paintings draw me out. But nothing like the space and form, the rhythms in the air, the play on materials, of sculpture.

The biggest takeaway from this written piece is the journey. You have done an incredible job in a very short essay of giving the reader a very complete visual journey to experience the transitions from the most simpler frontal perspective and relief all the way through abstraction. The air moves with us around each image as we imagine being in its presence. Using the Degas as the transitional pivot places it in context casual viewers could never realize on their own, and academics often overlook.

Your writing is a true service to art, and history will be richer for it.