Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Holy Week and the celebration of Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The narrative of Palm Sunday is anchored in the four canonical Gospels (Matthew 21, Mark 11, Luke 19, John 12). Each account recounts how Jesus rode into Jerusalem on a donkey while crowds laid down cloaks and palm branches; an act loaded with theological significance. The use of a donkey (a creature emblematic of peace) fulfills Zechariah 9:9, underscoring themes of humility and the unconventional nature of Christ’s kingship, as opposed to worldly power (The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version). These texts invite readers to view the event both historically and as a symbolic fulfillment of prophetic tradition, establishing a foundation for later iconographic treatments in art and liturgy.

“Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter of Jerusalem! See, your king is coming to you, righteous and victorious, lowly and riding on a donkey…” (Zechariah 9:9, NRSV).

This narrative, woven with theological motifs of peace and sacrificial kingship, remains a touchstone for Christian identity and has been extensively discussed in biblical scholarship (Evans, The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew–Luke 381–395).

The palm branch has long been a multifaceted symbol in religious art. In antiquity, palms signified victory in Greco-Roman and Near Eastern cultures; gladiators and athletes alike were crowned with them to denote triumph (Nigosian, Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices 112). Early Christians adopted this symbol, using it to represent both the triumph over sin and death and the hope of eternal life; a theme underscored by its repeated appearance in depictions of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem.

In later Christian art, the palm branch evolved into an emblem of martyrdom and spiritual victory, frequently appearing in scenes of holy celebration and in representations of sanctified relics (Blum, Early Netherlandish Triptychs: A Study in Patronage 256–258). The continuity of this symbol from ancient ritual to Christian liturgy illustrates its enduring power in communicating victory, peace, and eternal life.

The palm branch, as seen today in Palm Sunday processions, continues to serve as a potent emblem of triumph and the promise of resurrection (“Palm Branch,” Wikipedia).

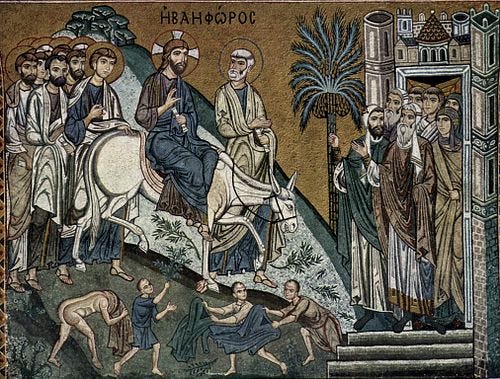

In the art of the early church and the Byzantine period, Palm Sunday imagery was rendered with a deliberate simplicity, emphasizing iconographic symbolism over naturalistic detail. Mosaics, such as those at Santa Pudenziana in Rome, use abstracted palm motifs and processional figures to evoke both the festal nature of the event and the collective identity of the Christian community (Cameron, The Byzantines 87–92).

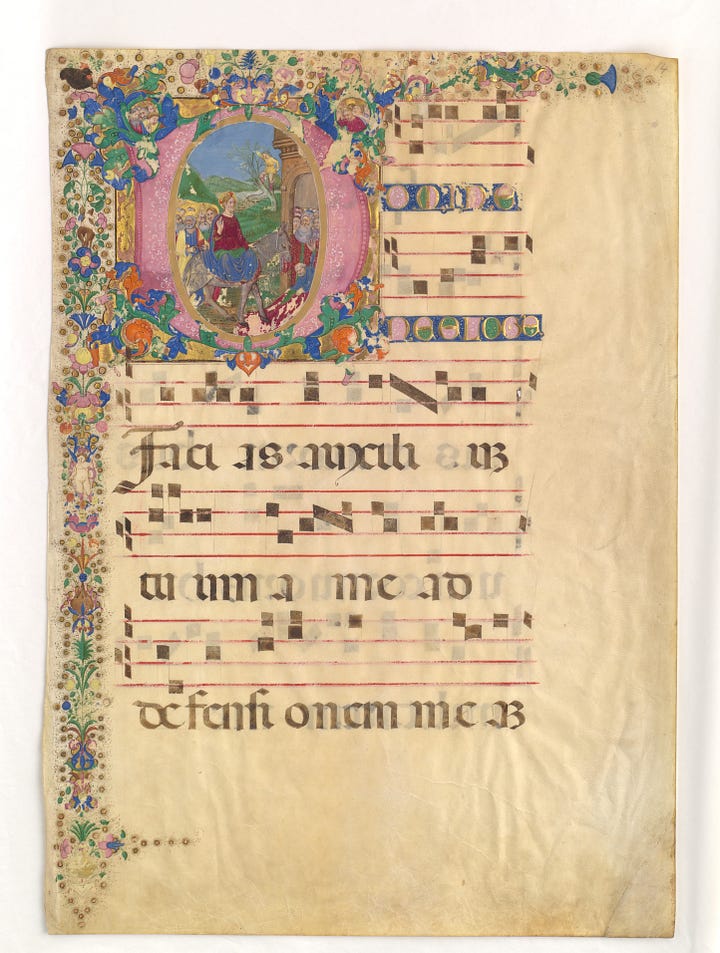

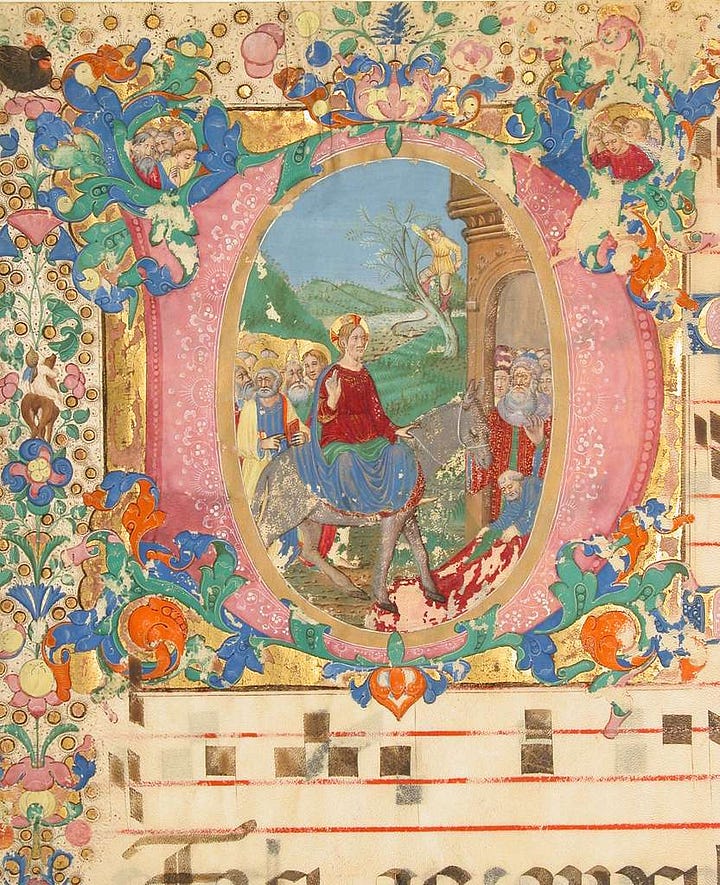

Additionally, illuminated manuscript leaves, like the one from Bartolomeo di Domenico di Guido housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, demonstrate how Palm Sunday narratives were transmitted visually among a largely illiterate population. These early depictions set stylistic precedents for later artistic representations by emphasizing hierarchical scale, flattened forms, and symbol-laden gestures that aimed to express the transcendent significance of Christ’s entry (Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Manuscript Leaf with Entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday”).

During the Middle Ages, Palm Sunday was both a subject of illuminated manuscripts and an active component of liturgical drama. Illuminated texts, such as those in The Stuttgart Psalter, combine richly decorated initials, marginalia, and narrative scenes to animate the biblical story for congregants who could not read (Rogers 142–148). Liturgical plays, often performed during feast days, transformed the solemn narrative into a communal spectacle, reinforcing the message of sacrifice and redemption through embodied ritual.

These performances and manuscripts not only served as educational tools but also fostered an immersive communal experience that linked scriptural history with lived devotion (Bennett, Ritual and Art in Medieval Christianity 98–101). The dramatic staging of Palm Sunday allowed medieval audiences to witness the unfolding of a sacred story in a manner that united art, performance, and theology.

The Renaissance heralded a dramatic shift in artistic techniques, emphasizing naturalism, spatial depth, and humanistic expression. Artists such as Giotto, whose revolutionary fresco “The Entry into Jerusalem” in the Scrovegni Chapel (Padua, c. 1305) prefigured naturalistic representation, laid the groundwork for later innovations (Lee and Robinson, Indianapolis Museum of Art: Highlights of the Collection). Giotto’s work moved away from the Byzantine style toward a more human-centered approach, capturing the emotional immediacy of the moment through realistic figures and spatial organization.

Later Renaissance masters, Duccio in his Maestà Altarpiece and Fra Angelico in works like Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, further refined these techniques. They integrated linear perspective, dramatic use of light and shadow, and carefully modeled figures to create a convincing illusion of three-dimensional space. These innovations not only fulfilled the narrative’s spiritual role but also enabled viewers to engage with the scene on a sensory level (Hall, Art and the Renaissance: A Study in Spatial Innovation 205–210).

Additional artworks like Giotto’s celebrated interpretation have been compared with those of Duccio and Fra Angelico to reveal the evolution of narrative depth and technical mastery during the Renaissance, underscoring the period’s commitment to both aesthetic beauty and theological clarity.

The Baroque period brought forth a heightened sense of drama and emotional intensity in the depiction of Palm Sunday. Artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, El Greco, and Anthony van Dyck infused their works with dynamic compositions, dramatic lighting, and powerful gestural expressiveness. Rubens’s vibrant canvases exemplify the theatricality of Baroque art, using intense contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to animate scenes of Christ’s entry and to evoke visceral emotional responses (Smith 167–171).

Van Dyck’s 1617 oil painting Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, housed at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, is a prime example of Baroque dramatic composition. In his depiction, the exuberant crowd, sweeping gestures, and vibrant hues capture the paradox of a peaceful yet triumphant king entering a tumultuous city, echoing themes of both spiritual victory and impending sacrifice (Day, Indianapolis Museum of Art Collections Handbook).

El Greco further contributed to this tradition by rendering elongated figures and exaggerated movements that heighten the viewer’s sense of divine mystery and emotional engagement. In Baroque art, the interplay of theatrical lighting and dynamic movement transforms a biblical event into a vivid spectacle; a celebration of both physical and spiritual triumph.

Central to the Palm Sunday narrative is the motif of the donkey; a symbol laden with contrasting meanings. In biblical terms, the donkey represents peace and humility, standing in stark contrast to the warhorse of a conquering king. Early Christian art consistently portrayed Christ riding a donkey as a fulfillment of prophecy (Zechariah 9:9), underscoring His role as the “Prince of Peace” (The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version).

Art historians note that Byzantine and later Renaissance depictions adapted this motif in varying degrees. Paul Jennings’s study, “The Donkey in Christian Iconography: From Humility to Symbol,” examines how early representations were markedly austere, reflecting the simplicity and humility of Christ’s mission, while later naturalistic treatments, seen in works by Duccio and Fra Angelico, embed the donkey within a broader narrative of redemption (Jennings 55–62). The donkey’s enduring presence in Palm Sunday art highlights its powerful symbolic resonance as an emblem of peaceful, sacrificial kingship.

Palm Sunday has been reinterpreted across different cultures and artistic traditions, generating distinct visual vocabularies that reflect regional values and aesthetic preferences. In Western Europe, large-scale processional depictions often emphasize the exuberance of joyful crowds, lavish pageantry, and detailed landscape backdrops, as seen in Rubens’s and van Dyck’s portrayals. In contrast, Eastern Orthodox iconography tends toward a stylized, hieratic simplicity, where figures are rendered in a manner that emphasizes transcendence and spiritual abstraction (Lopez, Global Visions: The Cross and Cultural Diversity in Christian Art 134–137).

Latin American interpretations, for instance, may incorporate indigenous motifs and local flora (such as woven palm fronds) to express a syncretic blend of Catholic symbolism with native artistic traditions. An example is the work of Efstathios Karousos’s 1780 tempera painting Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, which, while rooted in the Byzantine tradition, is rendered in a style reflective of the Heptanese School’s fusion of Neapolitan naturalism and Greek iconography (Karousos, “Entry of Christ into Jerusalem,” Wikipedia). These cultural variations attest to the adaptability of Palm Sunday imagery, revealing both local spiritual concerns and broader universal themes.

The liturgical observances of Palm Sunday have continuously influenced its artistic representations. Palm processions, where worshippers receive and then later burn palms to create the ashes for Ash Wednesday, reinforce the narrative of Christ’s entry and the cycle of passion and redemption. Ritualistic gestures such as the blessing of palms and the re-enactment of the procession have been integrated into church architecture and decoration, often mirrored in visual art (Kirk, “Ideas for Displaying Palm Sunday Palms Around Your Home”).

Church frescoes, triumphal arches, and congregational processions depicted in paintings and stained glass windows attest to this close relationship between liturgy and art. Jane Bennett’s work, Ritual and Art in Medieval Christianity, shows how these rituals not only provided a living context for biblical narratives but also generated recurring visual motifs that shaped artistic production from the medieval period onward (Bennett 98–101). The integration of ritual practice and visual representation ensures that Palm Sunday remains a vibrant part of communal worship and artistic tradition.

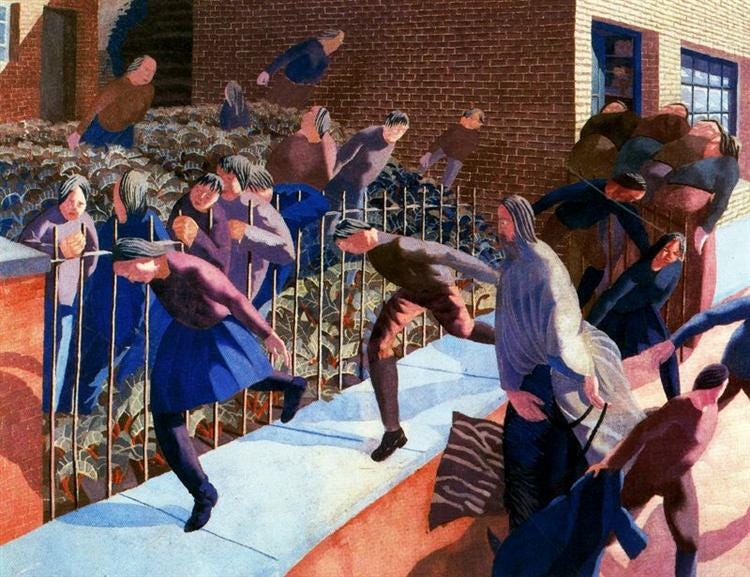

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, artists have revisited Palm Sunday themes with innovative techniques and diverse media, reflecting shifts in cultural, theological, and aesthetic paradigms. Stanley Spencer’s modern reinterpretation in works like Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem recontextualizes the traditional narrative within a contemporary, sometimes abstract framework, exploring themes of nostalgia, memory, and transformation (Morrison, “Contemporary Voices and the Reimagining of Sacred Narratives” 77–84).

Contemporary multimedia installations and abstract paintings challenge conventional iconography by deconstructing the familiar symbols (palm branches, donkeys, processions) and reassembling them into fragmented or reimagined forms. These modern works frequently interrogate the secularization of religious symbols while affirming their capacity to evoke deep spiritual and historical resonance. In an era of pluralism and rapid cultural change, such reinterpretations underline the enduring relevance of Palm Sunday, inviting viewers to reconsider its ancient message in light of contemporary experience (Morrison 80).

Additional exhibitions, such as the 2017 Louvre show Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting, have highlighted how historical themes can be reinterpreted to dialogue with modern artistic concerns, bridging the gap between past conventions and innovative practices.

References:

Bennett, Jane. Ritual and Art in Medieval Christianity. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Blum, Shirley Neilsen. Early Netherlandish Triptychs: A Study in Patronage. University of California Press, 1969.

Cameron, Averil. The Byzantines. Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Evans, Craig A. The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: Matthew–Luke. B&H Publishing Group, 2003.

Hall, Michael. Art and the Renaissance: A Study in Spatial Innovation. Phaidon Press, 1999.

Jennings, Paul. The Donkey in Christian Iconography: From Humility to Symbol. Journal of Early Christian Art, vol. 12, no. 2, 2008, pp. 55–62.

Kirk, Lisa. Ideas for Displaying Palm Sunday Palms Around Your Home. Blessed Is She, 25 Mar. 2018, www.blessedishe.com.

Lopez, Robert. Global Visions: The Cross and Cultural Diversity in Christian Art. Yale University Press, 2012.

Morrison, Elizabeth. Contemporary Voices and the Reimagining of Sacred Narratives. Modern Theology Review, vol. 35, no. 3, 2018, pp. 75–84.

The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version. HarperCollins, 1991.

Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (van Dyck). Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entry_of_Christ_into_Jerusalem_(van_Dyck).

Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (Karousos). Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entry_of_Christ_into_Jerusalem_(Karousos).

This was great Rogue. Thank you!! 🙏🏻