Suzanne Valadon, born Marie-Clémentine Valadon in Bessines-sur-Gartempe, France, defied the gendered constraints of her era to become one of the most original voices of Post-Impressionism. Emerging from the bohemian milieu of Montmartre, Valadon transformed her experiences as a model, muse, and autodidact into a radical artistic practice that redefined representations of femininity. Unlike her male contemporaries, Valadon’s work rejected idealized female archetypes, instead foregrounding raw corporeality, psychological depth, and working-class subjectivity.

Valadon’s early life was marked by poverty and precarity. The illegitimate daughter of a laundress, she began working at age 11, first as a seamstress and later as a circus acrobat until a fall forced her to abandon the trade (Mathews 23). By her teens, she entered the Parisian art world as a model for Symbolist and Impressionist painters, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who immortalized her in works like Dance at Bougival (1883), and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who nicknamed her “Suzanne” after the biblical figure Susanna (Ireson 34). Her relationships with these artists provided informal training; she observed their techniques and absorbed their avant-garde sensibilities.

Valadon’s artistic breakthrough came under the mentorship of Edgar Degas, who recognized her talent for draftsmanship and encouraged her to exhibit. Degas’ influence is evident in her early drawings, such as Self-Portrait (1883), which combines precise contour lines with unflinching self-scrutiny (Rose 89). By 1894, Valadon became the first woman admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, a milestone that legitimized her transition from model to professional artist (Chadwick 289). Her later life was marked by financial struggles and personal tumult, including a turbulent relationship with her son, artist Maurice Utrillo, yet she continued producing groundbreaking work until her death in 1938.

Post-Impressionism’s emphasis on emotional expression, symbolic color, and structural rigor provided Valadon a framework to challenge artistic and social conventions. Her work synthesizes elements of Symbolism, Fauvism, and Expressionism, yet remains distinct in its focus on female agency. Valadon’s paintings are characterized by bold, sinuous outlines reminiscent of cloisonné, a technique she may have adapted from Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec (Garb 148). Her use of non-naturalistic color (vivid blues, greens, and ochres) evokes the emotional intensity of Gauguin, while her flattened perspectives and compressed spaces align with Cézanne’s geometric experimentation (Ireson 112). This synthesis of formal techniques allowed her to move beyond Impressionist depictions of fleeting light and instead emphasize structure, solidity, and psychological depth.

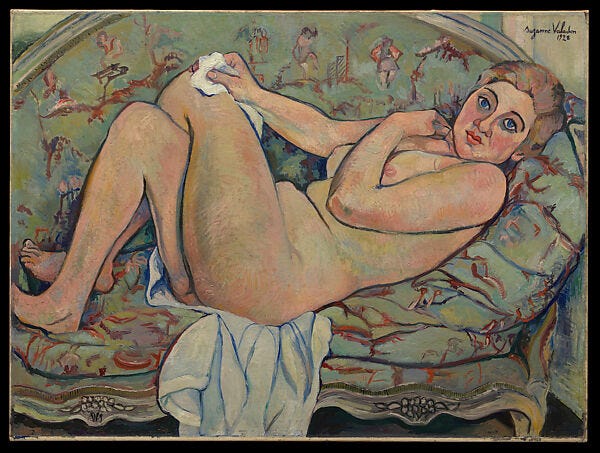

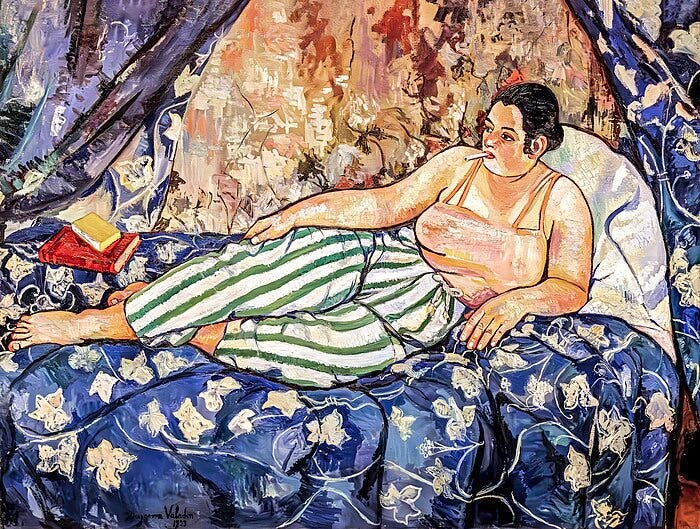

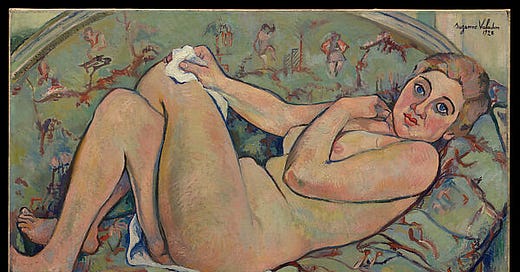

Her thematic focus further distinguished her from her male counterparts. Valadon’s subjects often subverted traditional genres, particularly in her depictions of the female nude. Unlike the passive, idealized figures of Ingres or Renoir, Valadon’s women possess muscular, unidealized bodies, their gazes confrontational rather than demure. In works such as Reclining Nude (1928), she disrupts conventional representations of femininity, depicting her subjects with a raw, unapologetic physicality that refuses the male gaze. Similarly, her domestic scenes, like The Blue Room (1923), portray women in states of repose or labor, their environments cluttered with symbolic objects that hint at inner lives (Pollock 76). These compositions reject the notion of women as decorative objects, instead positioning them as active, self-possessed individuals.

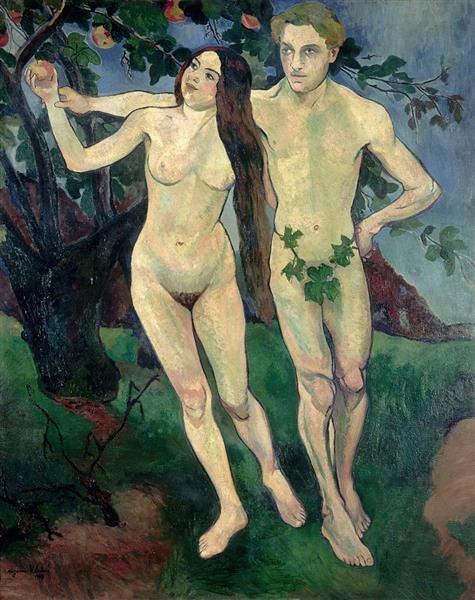

A particularly striking example of Valadon’s subversive approach is Adam and Eve (1909), where she inverts the biblical narrative: Eve stands assertively, offering the fruit to a hesitant Adam. The painting’s earthy palette and angular forms reject Renaissance idealism, instead emphasizing equality and mutual desire (Alsdorf 203). Through these stylistic and thematic choices, Valadon not only asserted her independence as an artist but also reshaped the visual language of Post-Impressionism, challenging both academic tradition and the gendered hierarchies embedded within it.

Valadon’s radical reimagining of traditional subject matter is perhaps best exemplified in her major works, which expand the Post-Impressionist canon by foregrounding female subjectivity and working-class life. The Blue Room (1923) is one of her most iconic paintings, featuring a reclining woman in a cramped, blue-hued interior, smoking a cigarette. The figure’s relaxed posture and direct gaze defy the passive eroticism of Ingres’ odalisques, instead asserting an autonomy that disrupts conventional representations of the female body. Art historian Nancy Ireson notes that Valadon’s use of clashing patterns and compressed space creates a “visual claustrophobia” that critiques domestic confinement (Ireson 132). The painting’s modernity lies in its fusion of Post-Impressionist color theory and feminist commentary, positioning it as a key work in early 20th-century art.

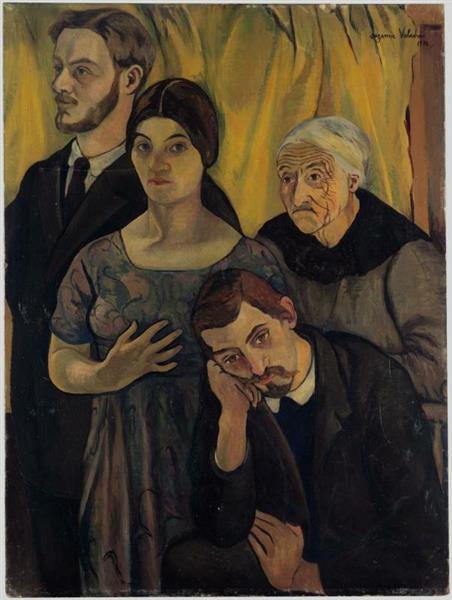

Similarly, Family Portrait (1912) reflects Valadon’s autobiographical approach, depicting her son Maurice Utrillo, her mother, and herself in an asymmetrical composition that conveys familial tension. The muted tones and rigid postures suggest an emotional detachment, while the inclusion of her aging mother challenges taboos around representing older women in fine art (Chadwick 294).

Valadon’s work has been reclaimed by feminist scholars as a radical intervention in art history. Tamar Garb argues that her nudes “refuse the male viewer’s voyeuristic pleasure” by emphasizing the subject’s autonomy (Garb 156). Unlike Renoir’s rosy, passive bathers, Valadon’s women are active participants in their own narratives, often depicted mid-movement or engaged in mundane tasks.

Her focus on working-class models (laundresses, circus performers, and mothers) also disrupts bourgeois ideals of femininity. As Patricia Mathews notes, Valadon’s The Abandoned Doll (1921), which portrays a nude adolescent girl, confronts the “cultural anxiety around female puberty” by rejecting both infantilization and sexualization (Mathews 89).

Though marginalized in mainstream narratives of Post-Impressionism, Valadon’s influence permeates 20th-century art. Recent retrospectives, such as the 2021 exhibition at the Barnes Foundation, have reignited scholarly interest, framing Valadon as a bridge between Impressionism and Modernism (Ireson 201). Critics initially dismissed her work as “primitive” or “naïve,” but contemporary scholars emphasize her intentional rejection of academic polish.

References:

Alsdorf, Bridget. Fellow Men: Fantin-Latour and the Problem of the Group in Nineteenth-Century French Painting. Princeton University Press, 2013.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. Thames & Hudson, 2020.

Garb, Tamar. Bodies of Modernity: Figure and Flesh in Fin-de-Siècle France. Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Ireson, Nancy. Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel. Yale University Press, 2021.

Mathews, Patricia. Passionate Discontent: Creativity, Gender, and French Symbolist Art. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art. Routledge, 1988.

Rose, June. Suzanne Valadon: Mistress of Montmartre. St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Very interesting how now I see the Degas / Manet show all over again in my head with her work right next to it. This was illuminating. A lot to think about and read more in-depth. I see a relationship in our earlier discussion now turning into: art-artist-muse-masterpiece.

Her story is compelling. I will find a bio, hopefully on your references, I can sink my teeth into.

She's one of my all time favorites and I'm so happy she's finally getting the attention she deserves. As you probably know, the Barnes Foundation just recently finally gave her an exhibition, and the Pompidou has a current show of hers before it closes for renovations. I live in Boston, and The Dance at the Bougival is everywhere: t-shirts, coffee cups, advertising The truth is, the real SV would have eaten that country bumpkin alive.