Tibetan Buddhist art emerged in the 7th–8th centuries CE alongside the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet under the Yarlung Dynasty. This was a period of dynamic cultural exchange, as Tibet lay at a crossroads of civilizations. Early Tibetan art was not created in isolation; on the contrary, the first Buddhist images and temple decorations were produced by artists from neighboring regions, notably India, Nepal, and China. King Songtsen Gampo’s marriage alliances with Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal and Princess Wencheng of Tang China are traditionally credited with bringing Buddhist images and craftsmen into Tibet. For example, Bhrikuti’s dowry included revered statues of Akshobhya, Maitreya, and Tara, which helped seed a Tibetan appreciation for Buddhist iconography. Early temples such as the Jokhang in Lhasa (c. 652 CE) were constructed and adorned through a tri-cultural collaboration; Tibetan builders, Newar (Nepalese) wood-carvers, and Chinese artisans worked together, integrating Nepali and Chinese aesthetic elements into the indigenous spatial sensibilities. The very layout of these sacred sites embodied multicultural design; the Jokhang’s architecture blended Nepali and Chinese features, and the first monastery Samye (founded 779 CE) was deliberately designed as a cosmogram or mandala of the Buddhist universe. According to accounts of Samye’s construction, its three-story temple had a bottom story in the Tibetan style, a middle with a Chinese-style roof, and an upper story topped by an Indian-style shikhara roof, symbolically uniting Tibet’s three primary artistic influences. Tibet in this era was remarkably open to foreign influence, and it eagerly absorbed the artistic vocabularies of India, Central Asia, China, and Nepal.

Foremost among these was the influence of Indian Buddhist art, which provided both religious content and stylistic models. From the 7th century onward, Tibetan rulers and monks maintained intensive ties with Indian Buddhism. Many Indian Buddhist teachers , accompanied by craftsmen carrying paintings, sculptures, and ritual objects, traveled to Tibet, especially during the 8th–12th centuries. These portable icons and manuscripts served as exemplars of Buddhist iconography and became templates for Tibetan artisans. Conversely, adventurous Tibetan monks journeyed to India (and Nepal) to study not only Buddhist doctrine but also the arts; they returned home as conduits of artistic knowledge and technique. In the formative period of Tibetan art, India’s stylistic impact was paramount. The classical artistic traditions of the Gandhara region, Kashmir, and northern India (the Bengal/Pāla style) all left a deep imprint. Meanwhile, Tibet’s proximity to Central Asia and China ensured that those regions also contributed motifs and methods: for instance, after the Muslim conquests in Central Asia (8th–10th c.), Buddhist monks from places like Khotan took refuge in Tibet, bringing with them central Asian aesthetic elements such as armored, warlike guardian deities in Central-Asian dress. Chinese artistic influence first arrived via the Tang dynasty in Songtsen Gampo’s time, introducing features like elegant curved roofs, open backgrounds in painting, diagonal composition, and delicate landscape details. In summary, the “origins” of Tibetan Buddhist art are truly intercultural; from the beginning Tibet assimilated Indian sacred forms, Nepalese craftsmanship, Chinese stylistic refinements, and even indigenous Bön and nomadic motifs, forging a syncretic artistic foundation.

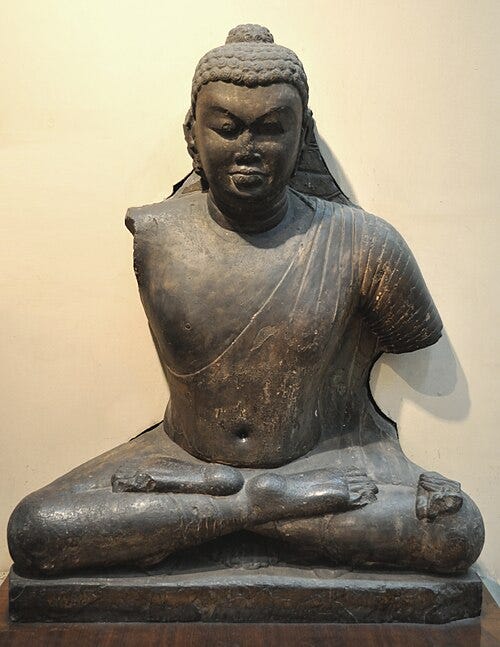

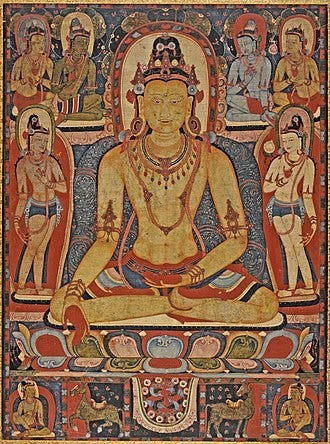

Underpinning many of Tibet’s early aesthetic choices were the ideals of Indian Gupta-period art (4th–6th century), which had formulated what came to be seen as the classical Buddha image. The Gupta style, celebrated as a golden age of Indian Buddhist art, achieved a synthesis of form that became the exemplar for later Buddhist art in India and beyond. Gupta Buddhas were portrayed with serene faces bearing a gentle downcast gaze, hair in snail-shell curls, elegant drapery either in string-folds or clinging transparent cloth, and proportions that conveyed a sensuous yet spiritual perfection. These features, refined at sites like Sarnath and Mathura in India, established the “ideal image” of the Buddha. Crucially, this Gupta Buddhist idiom was transmitted through subsequent centuries to Nepal’s Licchavi art and India’s Pāla art, which in turn heavily influenced Tibet. We see clear evidence of Gupta influence in the earliest Tibetan Buddhist sculptures and carvings. For example, 7th-century wooden carvings in the Jokhang temple, executed by Newar artists from the Kathmandu Valley, “express Nepalese Licchavi period (c.300–879) aesthetics, built on classic Indian Gupta period sculptural ideals,” indicating that those artists were fully versed in the Gupta tradition. The famous Jowo Shakyamuni statue in Lhasa (an image of the Buddha at age 12, brought according to legend by the Chinese princess) likewise reflects the refined, gently smiling style of late-Gupta and post-Gupta imagery. In painting, the Gupta conception of the Buddha’s form (with perfectly balanced features and a spiritual aura) survived through the Pāla dynasty and was passed on via Nepalese thangkas to Tibet. Thus, when Tibetan artisans began creating their own Buddha images, they inherited a Gupta-derived canon of iconometric proportions and idealized traits. Vidya Dehejia notes that Gupta Buddha images “became the model for future generations of artists,” including those in post-Gupta India, Nepal, and even as far afield as Indonesia and China. In Tibet’s case, these classical Indian prototypes taught artists how an enlightened being should appear: exuding inner calm, humane grace, and harmonious geometry. The lasting Gupta legacy in Tibet can be seen in the ubiquitous depiction of the Buddha with certain hallmark features, the ushnīsha cranial protuberance and lotus throne, the earth-touching or teaching hand mudrās, the eyes cast modestly down, all of which trace back to stylistic conventions first crystallized in Gupta art. In summary, while Tibet’s art evolved its own flavor, it remained anchored in the classical Indic paradigms established during the Gupta era, which imparted to Tibetan imagery a timeless, archetypal quality that continues to be revered.

Over the centuries, Tibetan Buddhist art developed a vast iconographic system to represent the multitude of divine figures and spiritual concepts in the tradition. The vast majority of surviving Tibetan art before the mid-20th century is religious, and thus its imagery is populated by Buddhas, bodhisattvas, meditational deities, saints, demons, mandalas and other sacred symbols, rather than secular subjects. Despite the diversity of forms, this iconography can be broadly categorized into a few key motifs:

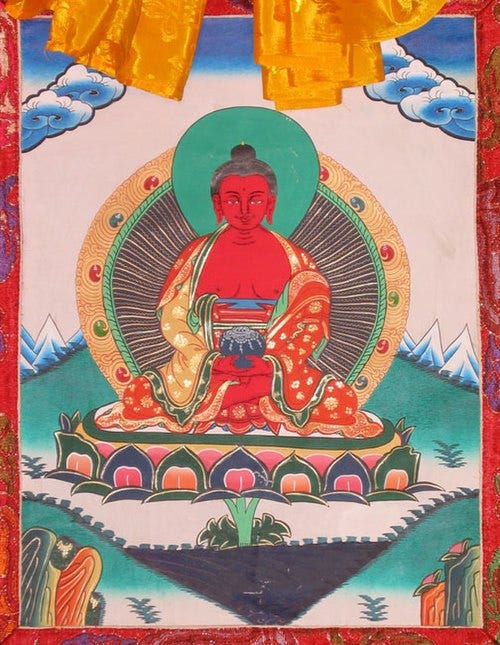

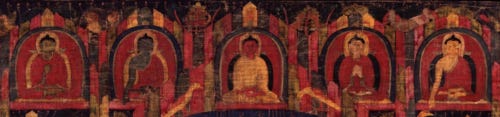

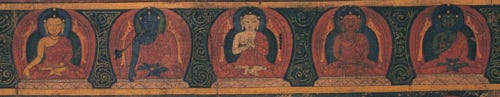

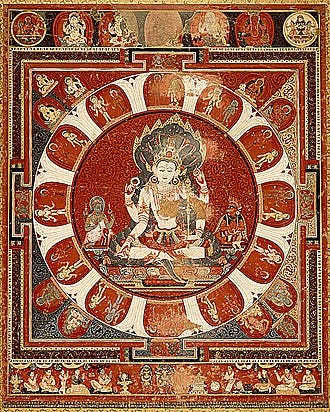

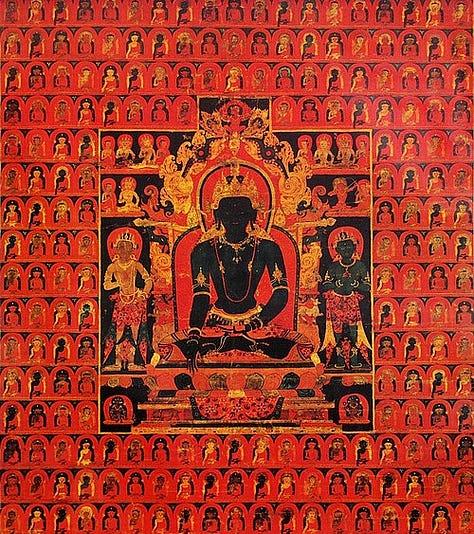

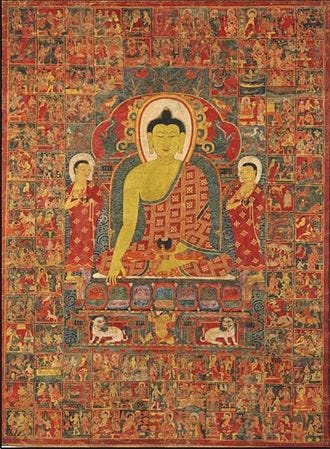

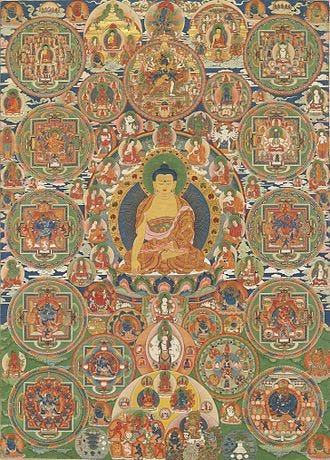

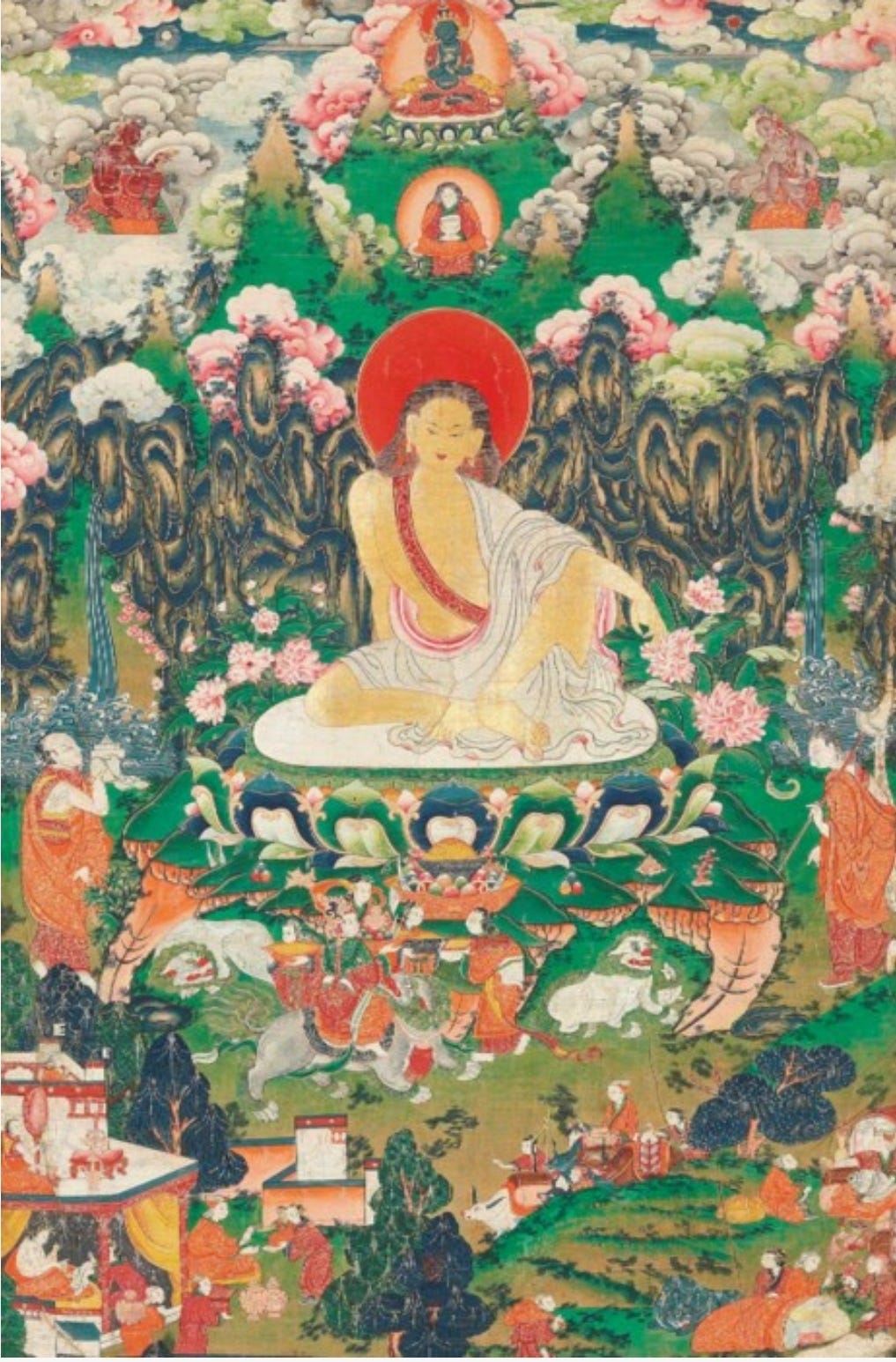

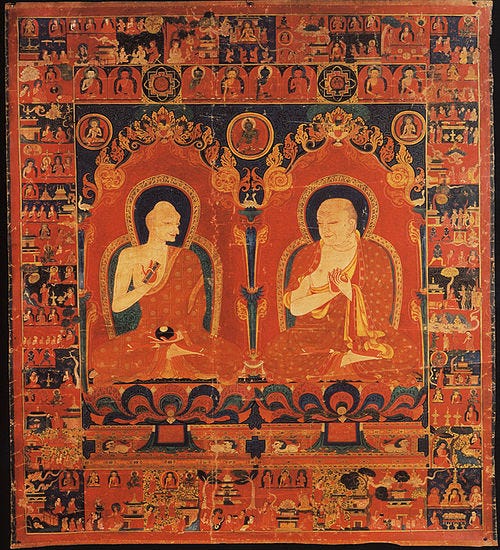

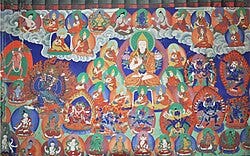

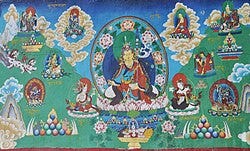

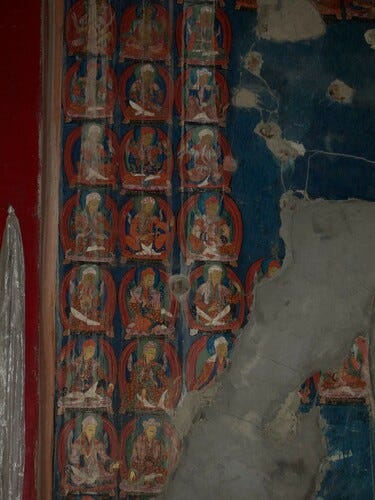

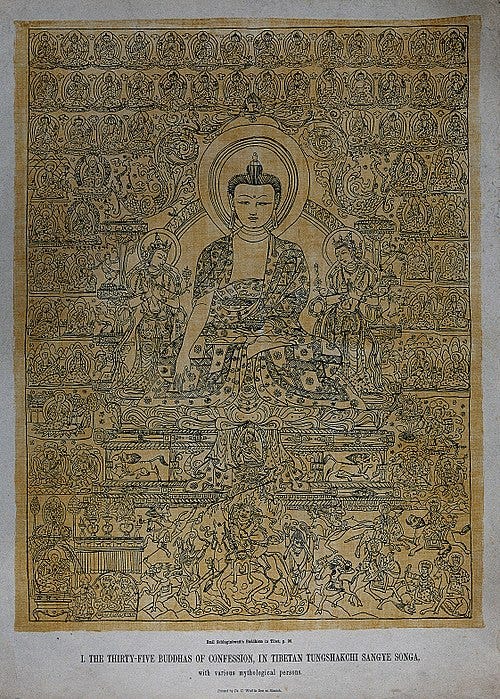

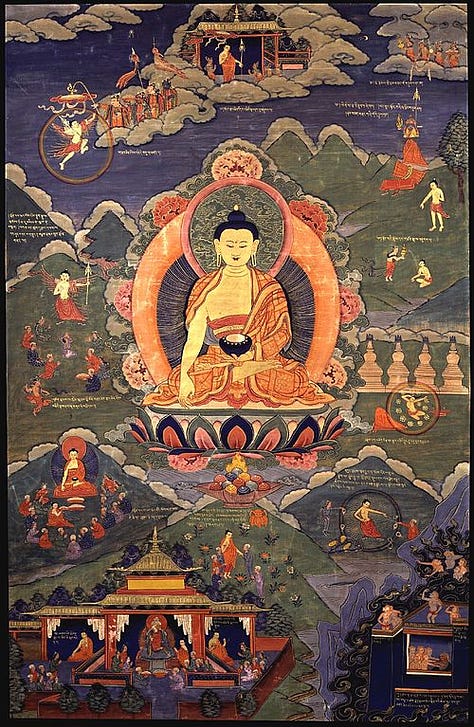

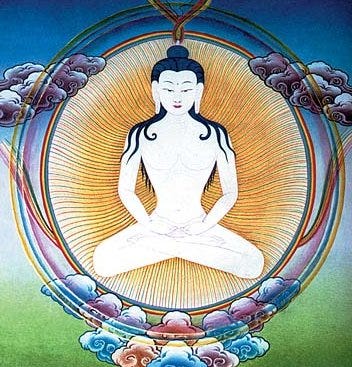

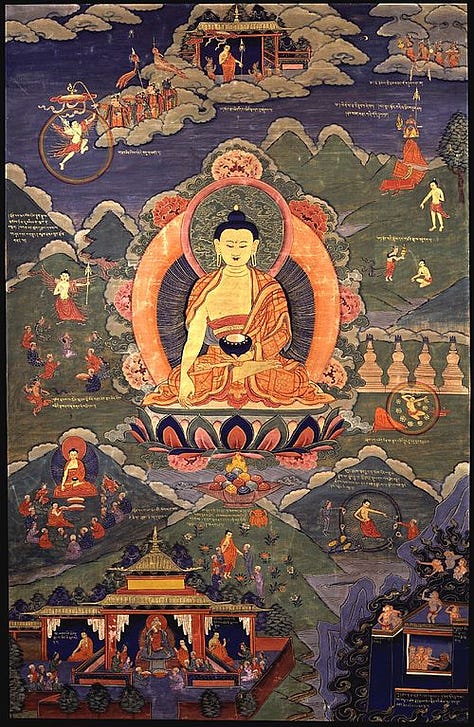

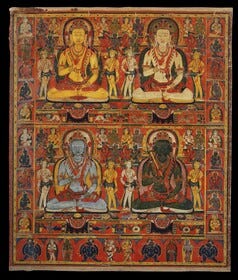

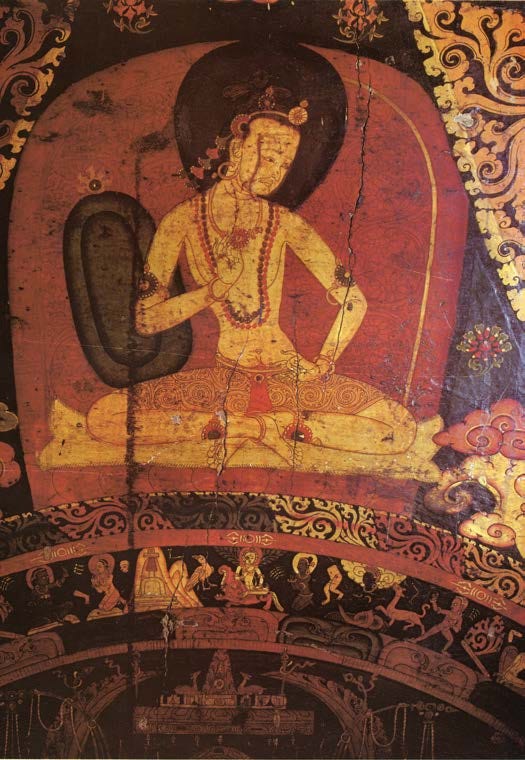

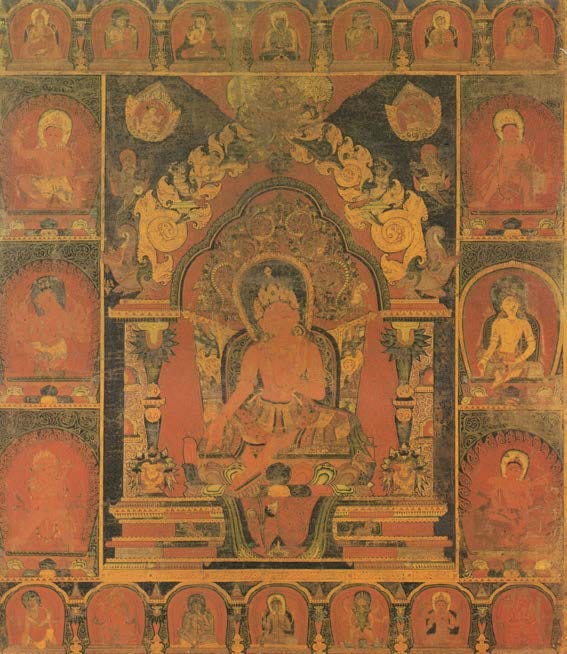

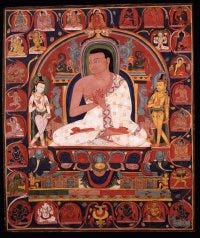

Buddhas are fully enlightened beings, typically depicted in serene meditation or teaching postures. Central among them is Shakyamuni Buddha, the historical Buddha, often shown seated on a lotus throne with a halo, performing mudrās like the bhūmisparśa (earth-touching gesture) or dharmacakra (teaching gesture). In Tibetan art, one also frequently encounters the Five Dhyani Buddhas (Vairocana, Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitābha, Amoghasiddhi), each associated with specific colors and symbols, and the Future Buddha Maitreya. These Buddhas are usually portrayed with tranquil facial expressions, elongated earlobes, ushnīsha topknots, and monastic robes, embodying the perfected qualities of enlightenment. For example, a painted thangka of Shakyamuni might show him flanked by his two chief disciples (as in a known 18th-century Tibetan thangka of Buddha with Maudgalyayana and Śāriputra). In Tibetan murals and scrolls, a large Buddha often occupies the central composition, with smaller Buddhas or disciples surrounding as attendants. Buddhas are generally depicted in peaceful form; with gentle features, harmonious proportions defined by strict iconometric canons, and often radiating an aura of rainbow light or backed by a nimbus.

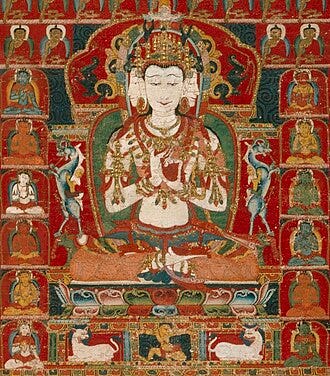

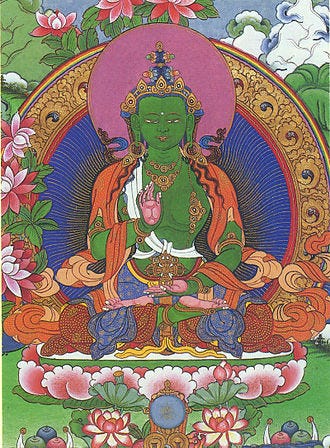

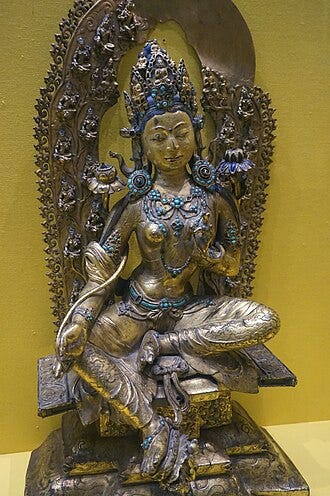

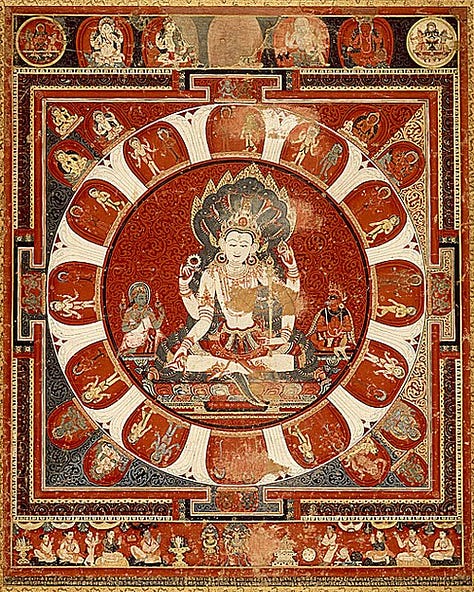

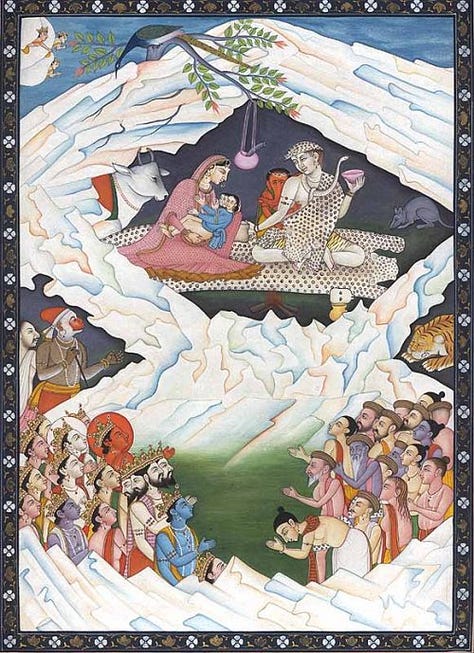

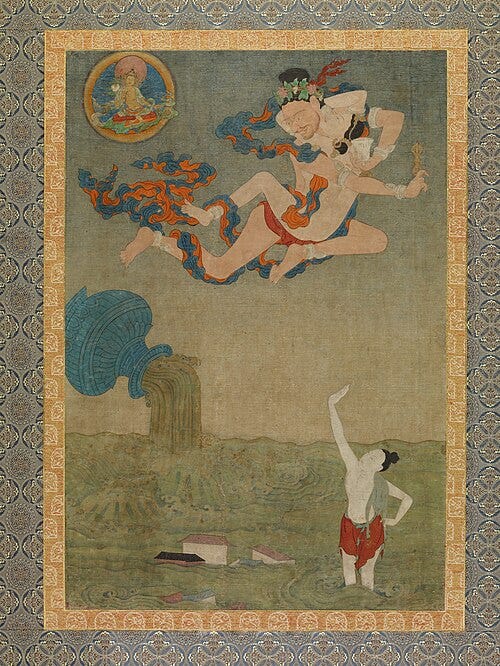

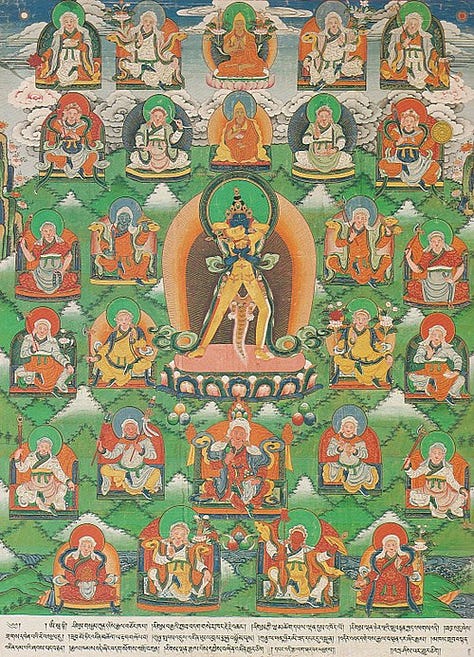

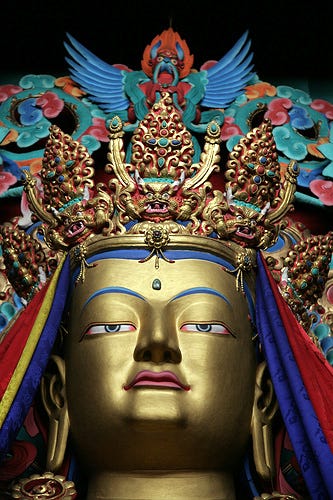

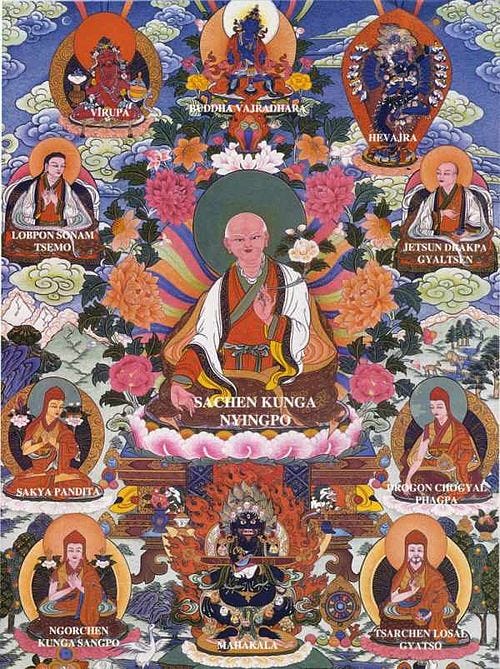

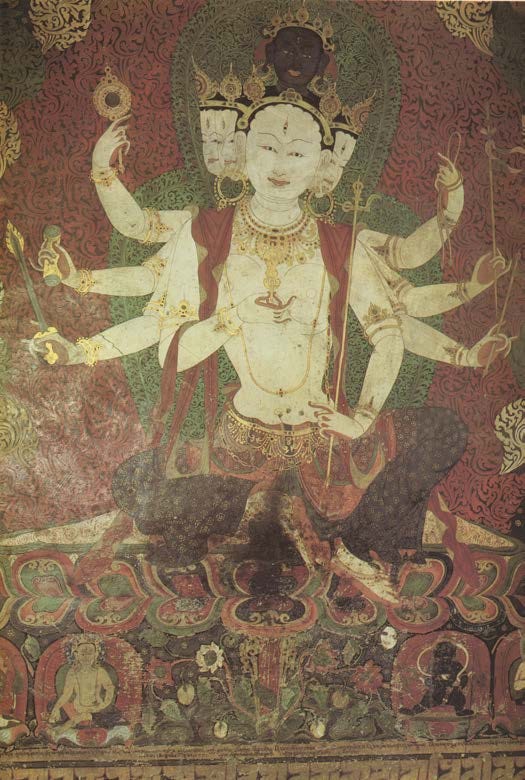

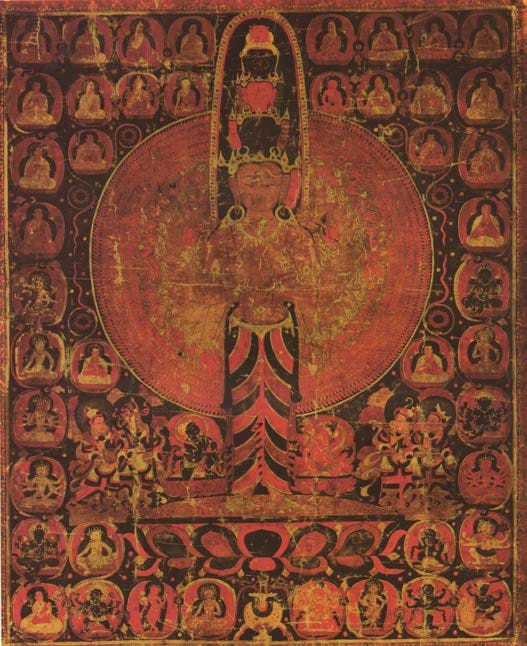

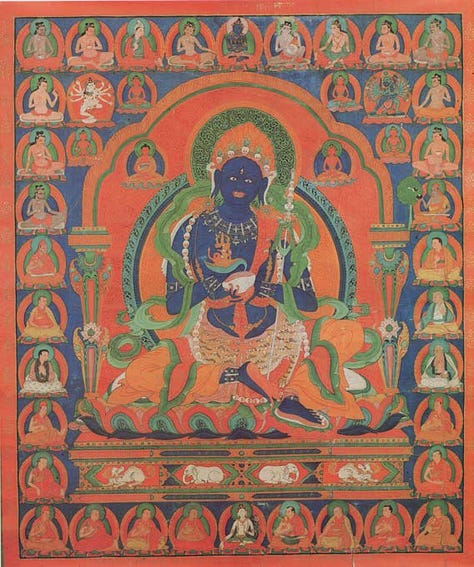

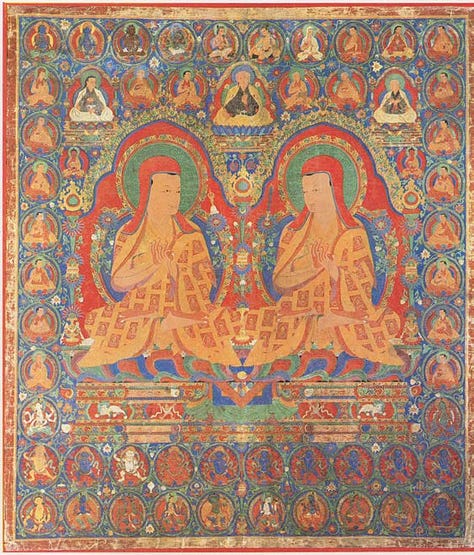

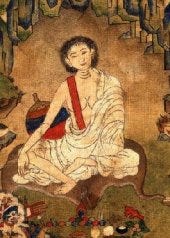

Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who forego final Buddhahood to compassionately assist others. Bodhisattvas in Tibetan art appear as radiant, bejeweled figures, often in princely attire (silks and crowns) to signify their remaining engagement with the world. Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig), the bodhisattva of compassion, is especially beloved in Tibet (the Dalai Lamas are believed to be his emanations), he can be shown in a simple two-armed form or in complex forms with 4 or 1000 arms, holding a lotus and prayer beads, epitomizing compassion. Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom, is typically golden-orange, wielding a flaming sword that cuts through ignorance, and holding a scripture. Tara, the female bodhisattva of mercy, is another iconic figure (Green Tara or White Tara varieties) depicted seated in royal ease, extending a hand in blessing. Bodhisattvas are rendered youthful and graceful, adorned with elaborate jewelry, crowns, and floating scarves. Their poses (āsanas) are often dynamic yet balanced, conveying both energy and poise. They gaze serenely, embodying compassion and wisdom. Tibetan iconography enumerates dozens of bodhisattvas and divine figures; however, all share some common visual grammar, a central head deity surrounded by retinues of smaller figures arranged symmetrically, creating a hierarchical but harmonious composition. These entourage figures can include other bodhisattvas, attendants, or human teachers, integrated into an intricate celestial assembly around the main deity.

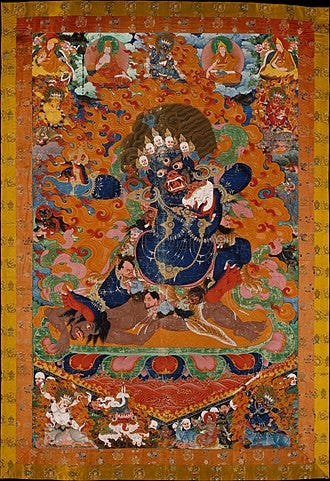

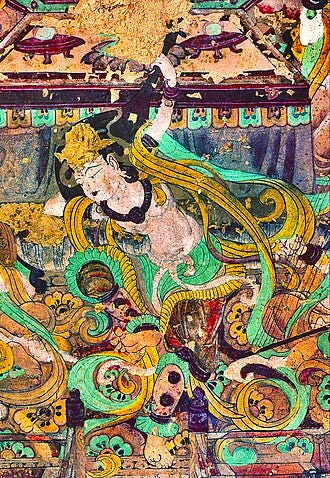

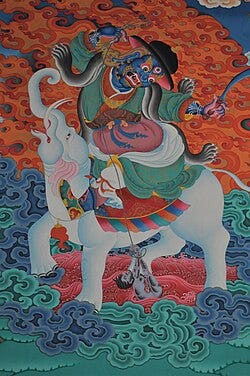

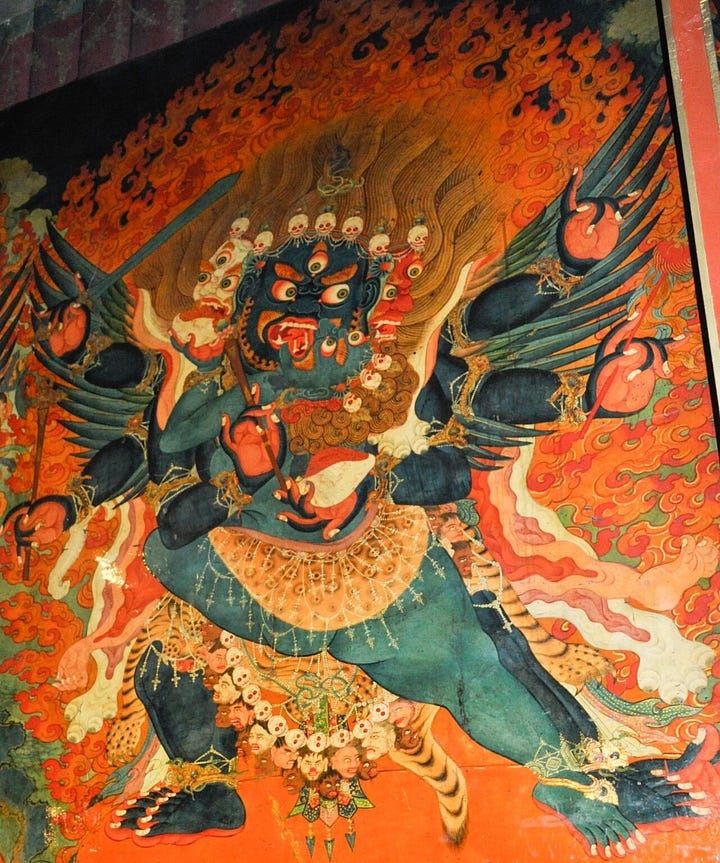

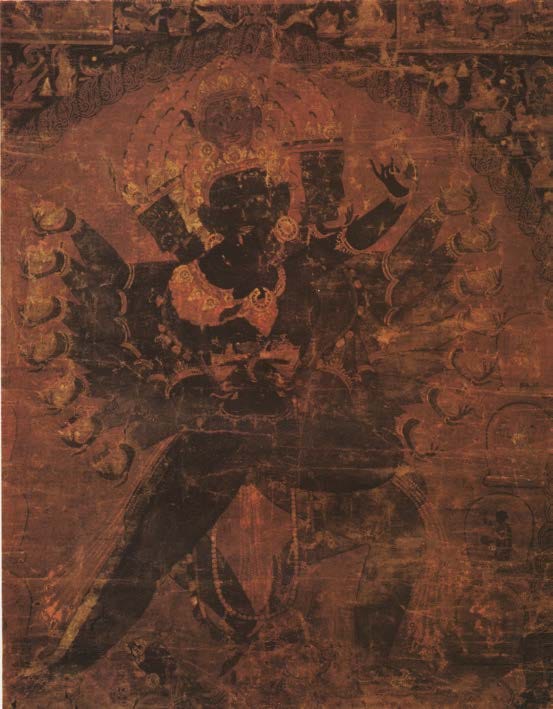

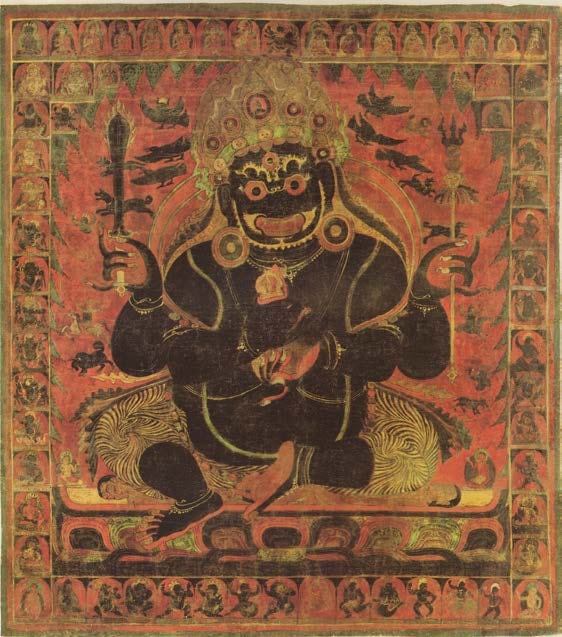

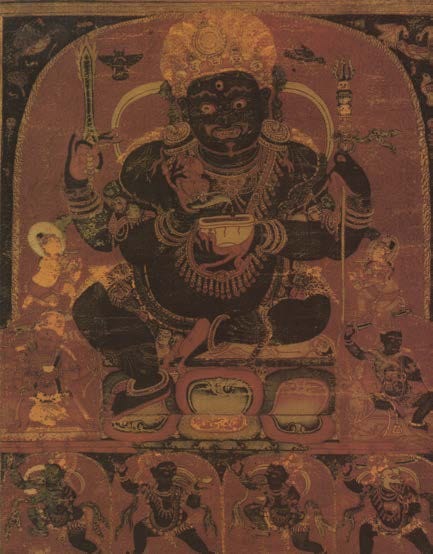

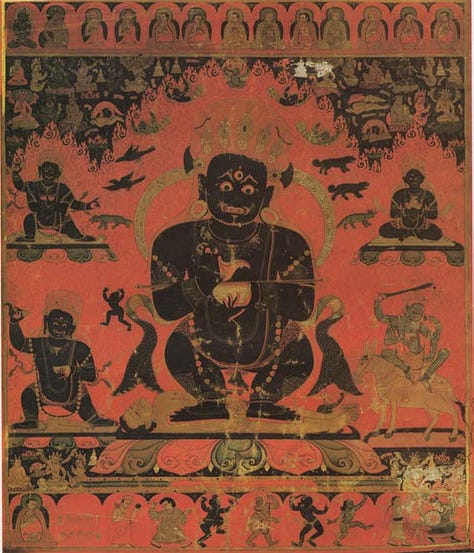

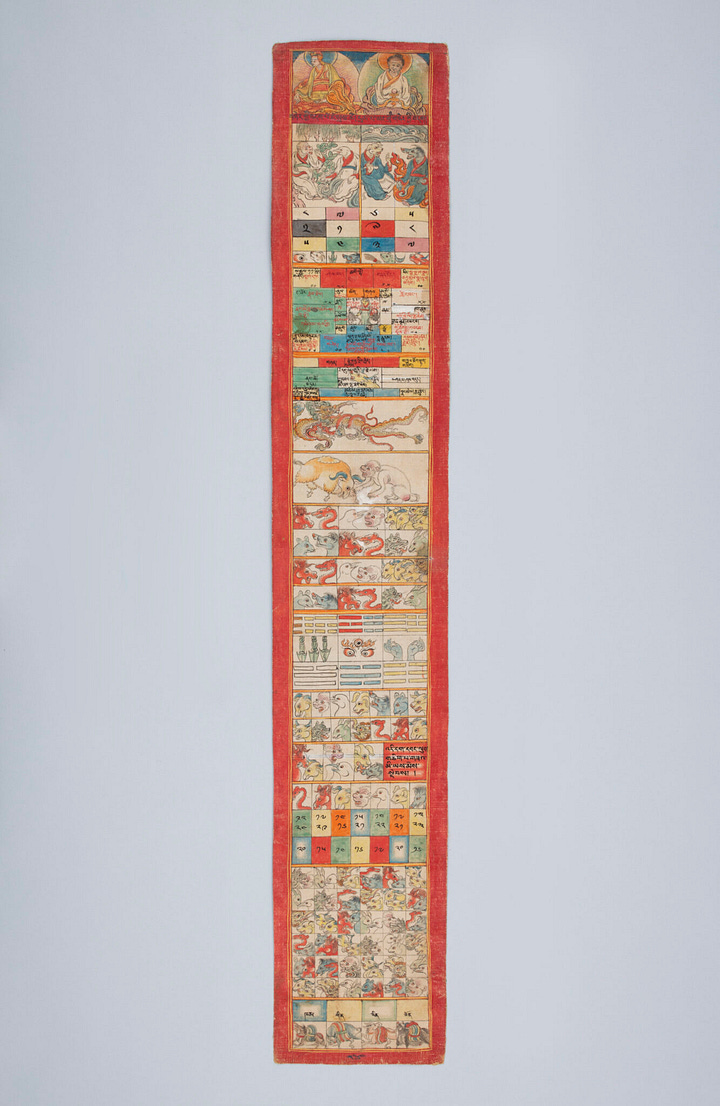

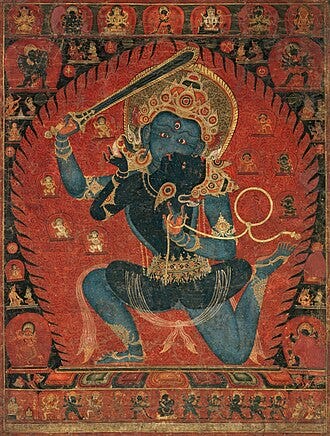

A striking category of Tibetan iconography is the wrathful or protective deities, known as dharmapālas and fierce tantric beings. These figures, such as Mahākāla (a form of Shiva as defender of the faith), Vajrabhairava (Yamantaka), Hayagriva, or Palden Lhamo, are depicted with terrifying iconography: monstrous fangs, wild hair, multiple arms brandishing weapons, and necklaces of skulls. They often trample on demons or symbolic obstacles. Despite their fearsome appearance, these wrathful deities are understood as manifestations of enlightened compassion in fierce form, protecting practitioners and overcoming inner negativities. Their iconography borrows from Indian Shaivite and Heruka imagery, as well as indigenous Bön animist motifs (many were originally local mountain gods subjugated into Buddhist service). In Tibetan paintings, wrathful deities are typically set against flames of wisdom fire, with dark or vibrant blue-red hues dominating. For example, a thangka of Vajrapani in wrathful form or Vajrayogini will show a ferocious expression, bulging eyes, and a halo of flames, symbolizing the burning of ignorance. These figures illustrate the tantric principle of using wrathful energy to conquer delusion; their terrifying forms are highly symbolic, not literal demons. Indeed, Tibetan tantric iconography is multilayered; a single deity may have peaceful and wrathful forms, multiple heads and arms to indicate manifold powers, and yab-yum (male-female in union) postures to represent the metaphysical union of wisdom (female) and compassion (male). Such symbols would be interpreted on several levels by initiates. As one scholar notes, the union of male and female so prevalent in Tantric art or the image of the tree of enlightenment are universal archetypal symbols, whereas other symbols like the vajra (thunderbolt sceptre) or padma (lotus) derive from Indian mythology but were adapted to express tantric concepts in a uniquely Tibetan way.

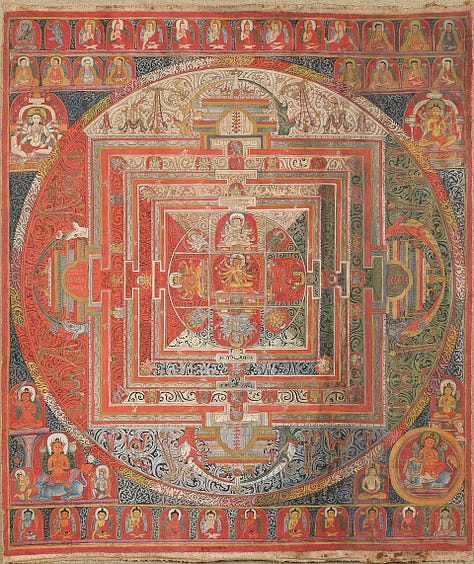

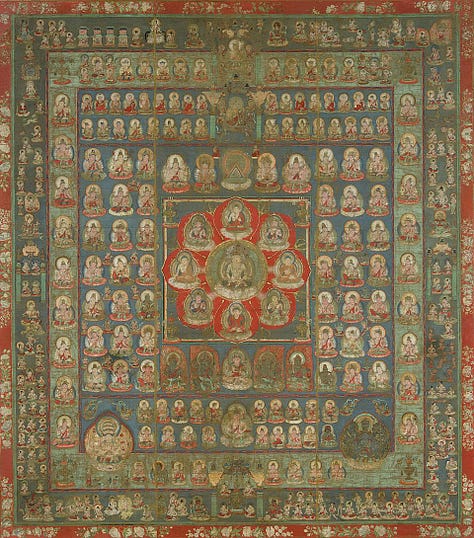

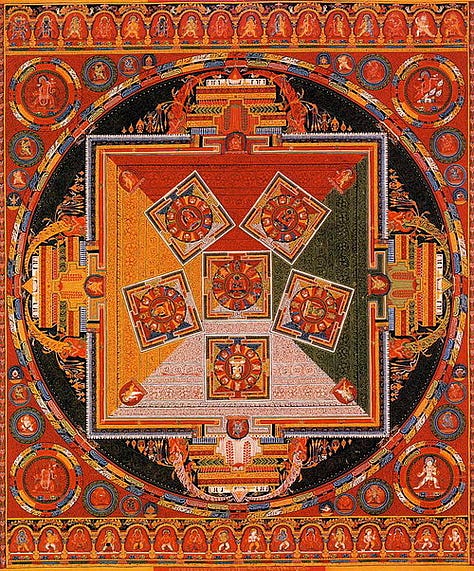

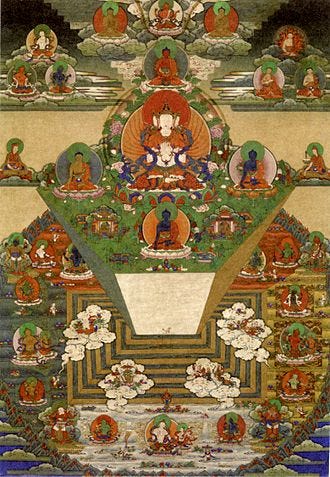

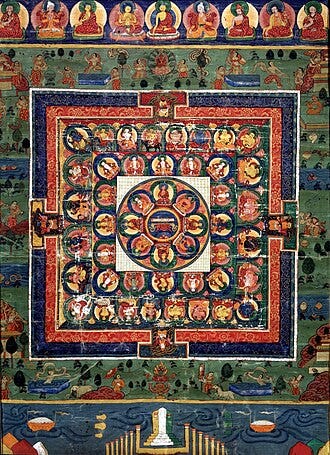

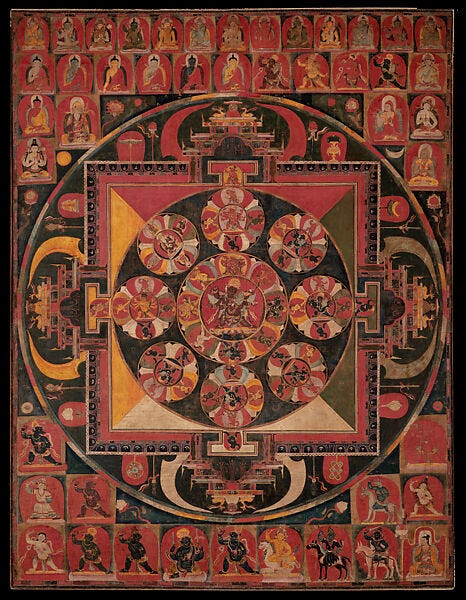

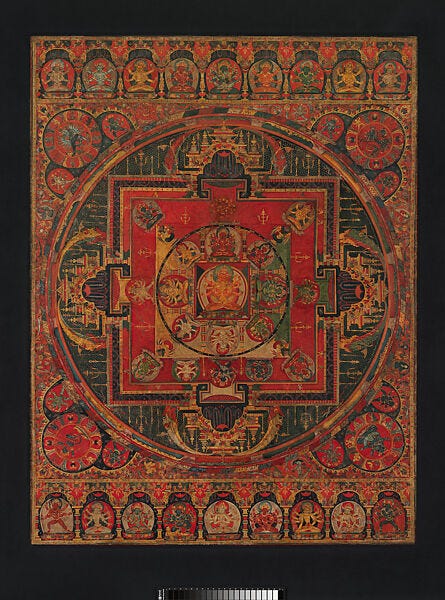

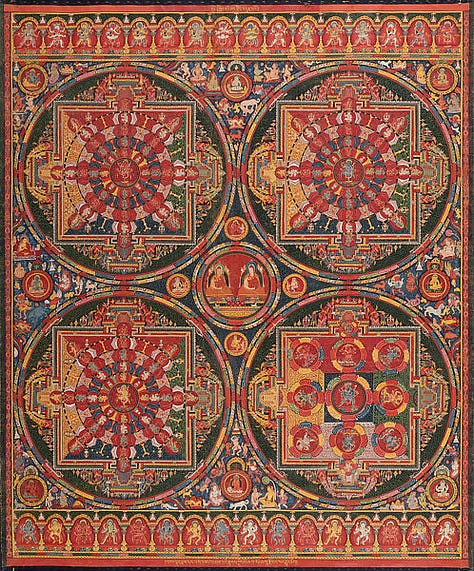

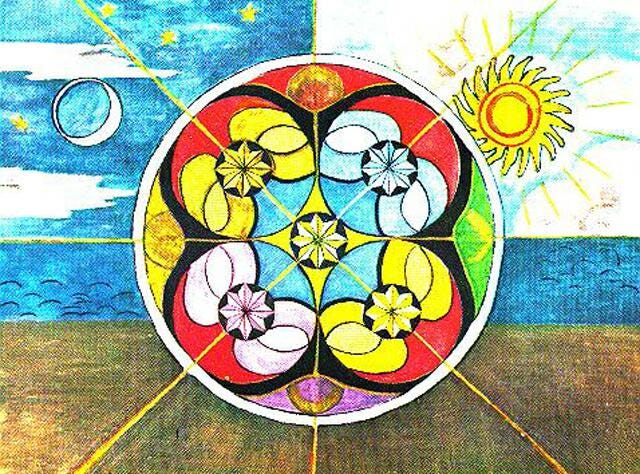

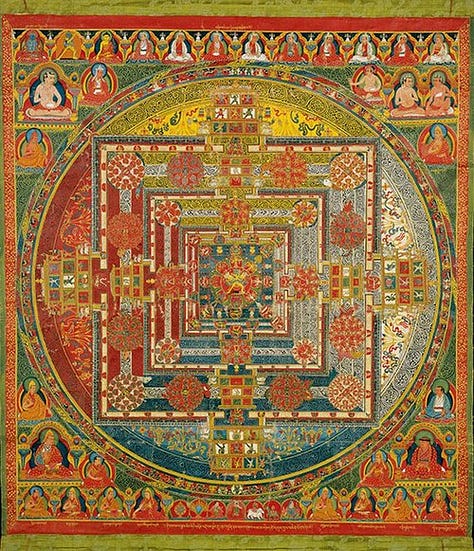

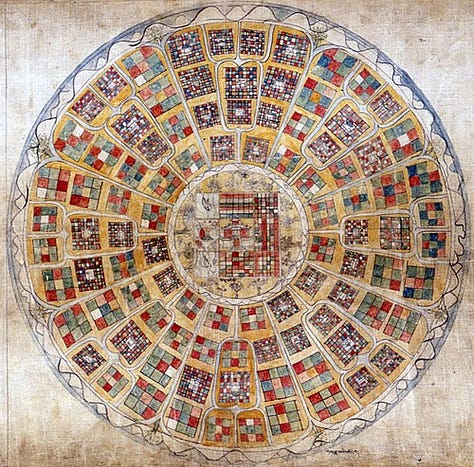

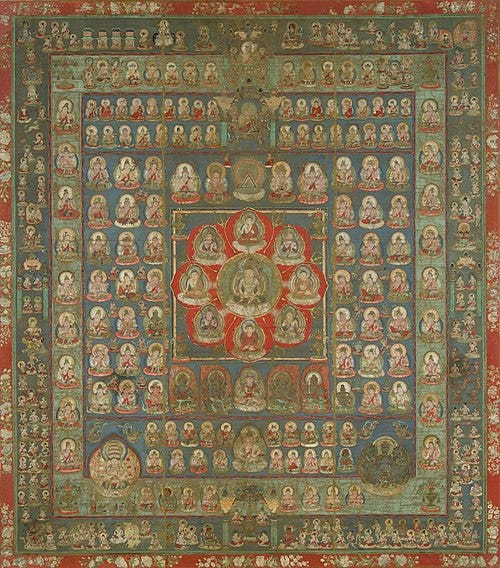

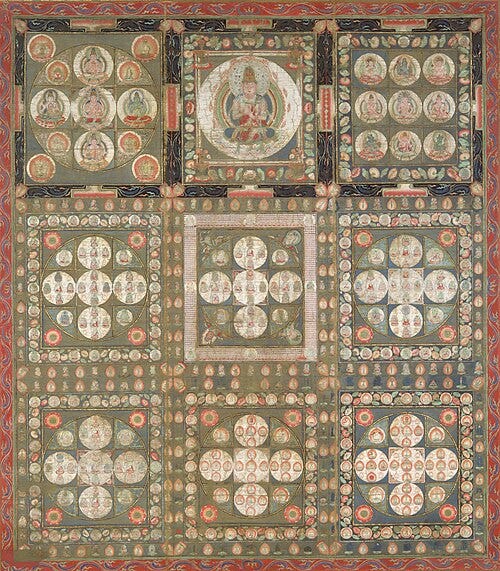

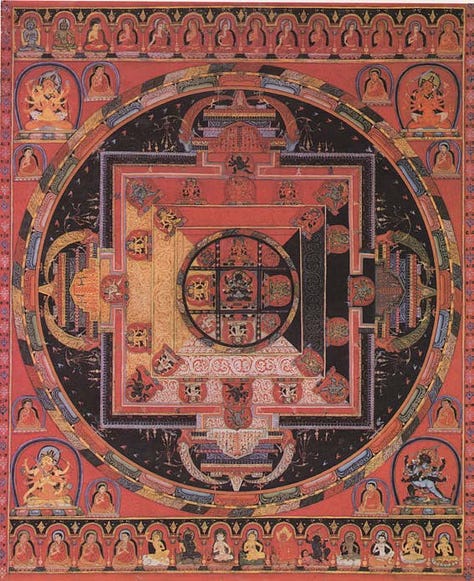

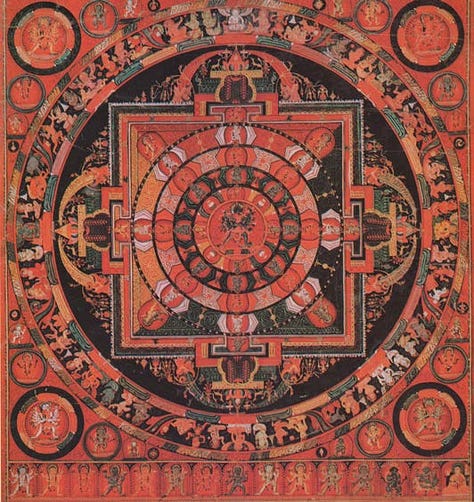

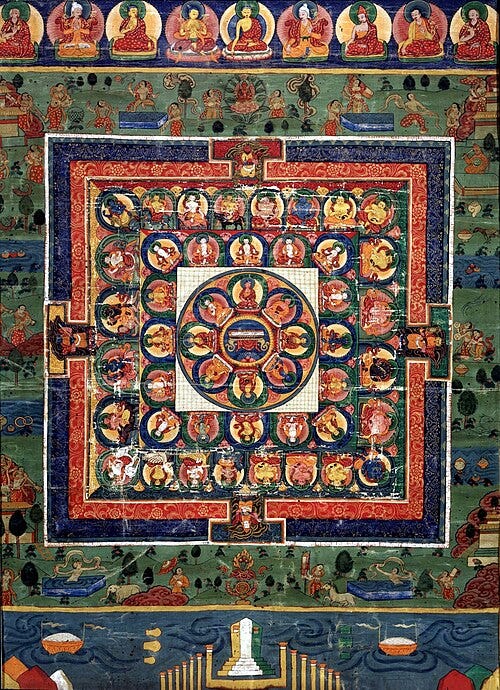

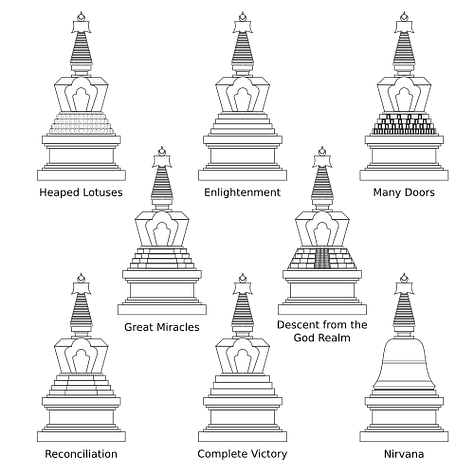

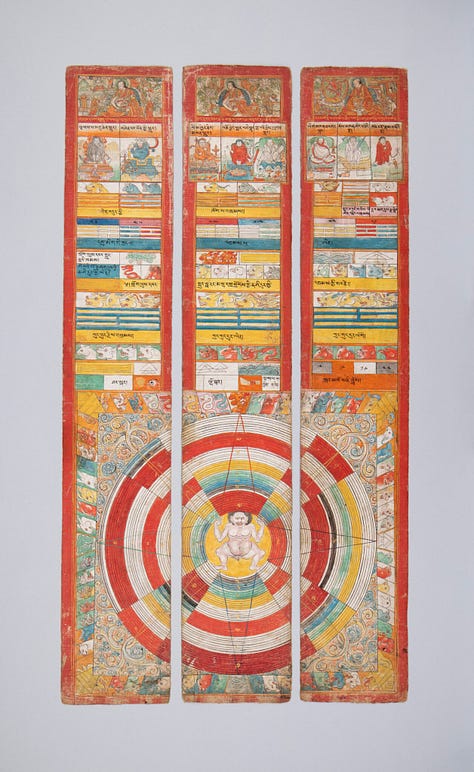

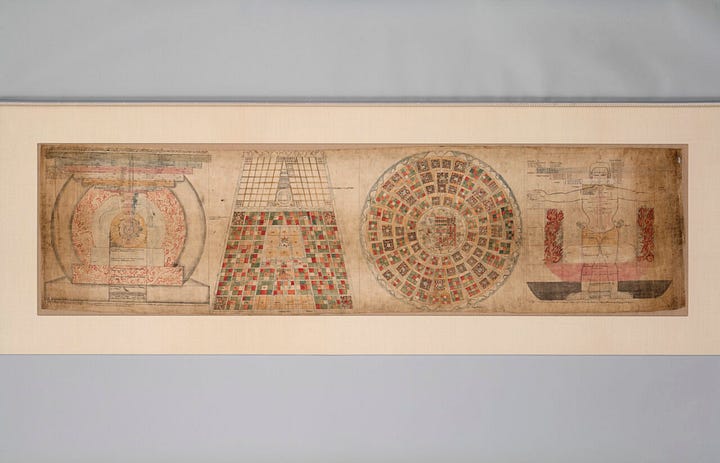

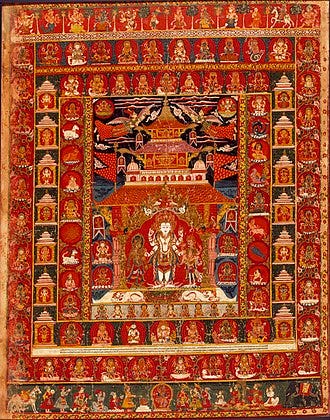

Beyond anthropomorphic figures, Tibetan art is rich in geometric symbolism. Chief among these are mandalas, intricate geometric diagrams, usually circular in form, that represent the perfected universe or a deity’s celestial palace. Mandalas are essentially blueprints of enlightened mind in diagrammatic form, mapping out sacred geometry and cosmology. In a typical mandala, a square palace with four gates is set within a circle, itself nested in concentric rings of flames, lotus petals, and cemeteries or cosmic oceans. Every shape and color has meaning: for instance, a circle enclosing a square symbolizes the union of heaven and earth, the transcendent contained within the worldly. Mandalas can be painted on scrolls, frescoed on monastery walls, or constructed three-dimensionally in architecture (as with the tiered design of certain temples). In iconography, mandalas are both art objects and ritual tools, monks visualize entering the mandala during meditation, and sand mandalas are ceremonially dismantled to teach impermanence. Alongside mandalas, other geometric symbols include the vajra-cross (visvavajra) representing stability, the three-dimensional stupas which are essentially architectural mandalas (more on this below), and astrological charts that often appear in medical or cosmological thangkas. Even the use of color in Tibetan art has symbolic geometry: the five primary colors (white, yellow, red, green, blue) correspond to the five cosmic Buddhas and their cardinal directions, organizing the composition of mandalas and statues. In sum, Tibetan Buddhist iconography is a highly codified visual language. Artists followed iconometric treatises to get every detail correct, from the proportions of a Buddha’s body to the attributes in a deity’s hands, because each element carries instructional meaning. The resulting images functioned as “visual scripture,” aids to teaching and contemplation as much as objects of beauty. A devotee, whether monastic or lay, could read these images: recognizing a figure’s identity by its color, hand gesture, and seat; discerning a deity’s mood (peaceful, wrathful) by its posture and expression; and even comprehending complex doctrines through allegorical tableaux. Thus, the key motifs of Tibetan art, Buddhas, bodhisattvas, wrathful protectors, and geometric mandalas, form an interconnected symbolic system that communicates the breadth of Buddhist philosophy and mythos through form and color.

One of the most distinctive art forms of Tibet is the thangka, a painted scroll on cloth that can be rolled up and transported. Thangka painting is a sacred art, often undertaken as a form of meditation and offered as an act of devotion. The creation of a thangka follows time-honored techniques and a strict visual grammar.

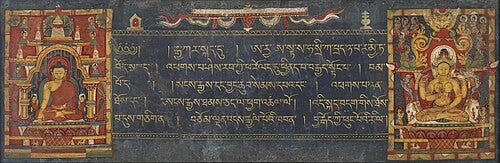

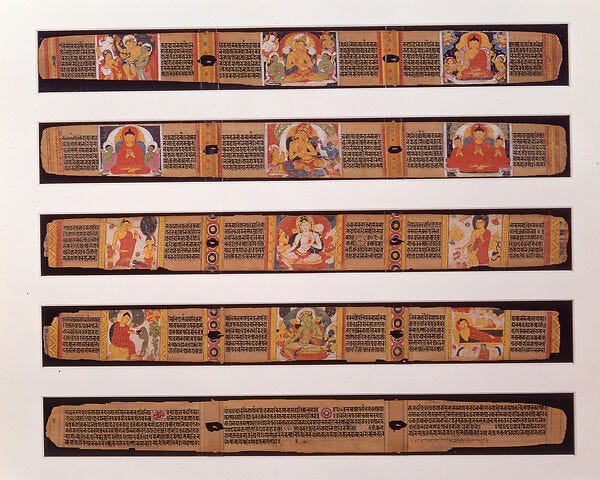

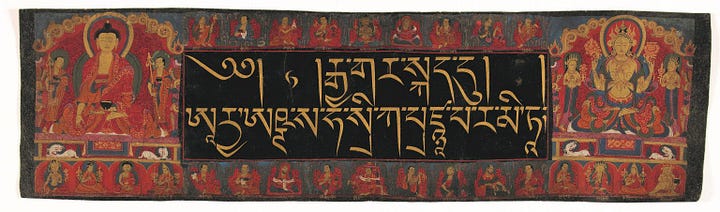

Thangkas are typically painted on a base of cotton canvas (and occasionally silk). The artist begins by stitching the cloth onto a wooden stretcher and applying a coat of gesso, a mixture of chalk (or yak bone white) and animal glue, to create a smooth, white surface. Once burnished to a sheen with a smooth stone, this canvas provides an ideal ground for mineral pigments. Traditional thangka painters use finely ground natural pigments: powdered minerals and semi-precious stones (for example, lapis lazuli for blues, malachite for greens, cinnabar for reds), as well as gold and silver leaf for highlighting. These pigments, mixed with animal glue or plant binder, produce the characteristically vivid yet earthy colors of Tibetan paintings. Brushes were historically made from animal hairs (e.g. squirrel, cat, or even peacock feather for fine lines), though today synthetic brushes are also used. The careful preparation of materials is itself a ritual: painters traditionally purify themselves by washing and sometimes reciting prayers or lighting incense before beginning work, setting a reverential tone.

The sketching of the composition on the primed canvas is guided by iconometric grids and measurements. Tibetan thangka painters follow canonical proportions laid out in scripture-like manuals (often ultimately derived from Indian iconometry texts). Using a charcoal or ink, the artist will mark a grid framework called tik-khang (“house of lines”), subdividing the surface so that the deities can be drawn with precision. Each figure (Buddhas, bodhisattvas, etc.) has a set number of facial units in height and specific alignments of eyes, nose, and mouth, etc. For example, a standing Buddha might be depicted as ten heads tall, with shoulders of a certain width relative to the head, and so forth. Apprentices spend years memorizing these proportional systems and the characteristic iconographic details of each deity. At first, they physically draw the grid on the canvas; as they mature in skill, the grid becomes internalized, enabling freehand yet proportionally accurate depiction. The initial line drawing (outlines of figures and major motifs) is usually done in red or black ink. In some workshops a master artist will sketch the principal figure, and students will fill in subsidiary elements.

Painting a thangka is a layered process, akin to building a world from background to foreground. After the outline, artists first apply flat areas of color to the background, often starting with the sky (deep blue or green), landscape elements, and architectural frames. Next comes the application of base colors to the main figures’ bodies and clothing. Shading and modeling are then used to give volume; Tibetan painters employ a technique of laying down a darker base tone and then adding lighter hues in tiny brush strokes (or vice versa) to create gentle tonal gradients, making silk appear to shimmer or muscles to curve. Traditional thankgas have a somewhat flat perspective, but volume is suggested by shading and highlights, especially on flesh and robes. A remarkable aspect of thangka coloring is the opaque yet luminous quality achieved, an effect produced by the mineral pigments (which give a matte, saturated color) combined with delicate shading. Once the larger color masses are finished, the artist adds fine details; the facial features of the deities are painted last, often by the master’s own hand as a sign of the painting’s spiritual completion. Eyes are “opened” in a small consecration ceremony once the thangka is otherwise complete. Gold is applied at final stages to enhance halos, jewelry, and decorative patterns. Indeed, many thangkas sparkle with gold highlights that catch the flicker of butter-lamp light in a dark shrine room.

After painting, a thangka is traditionally mounted in a rich silk brocade frame so it can be hung. Earlier thangkas were edged in plain blue or red silk, but by the later historical period, lavish multi-color brocades with floral motifs became common. The finished painting is sewn onto these textiles, with a thin silk cover flap attached at the top to protect the image when rolled. Wooden dowels are affixed at the bottom and top edges so the scroll can be rolled up and unrolled easily for display or transport. This portability was crucial in a land of nomads and missionaries, thangkas served as mobile murals, carried on yak-back from monastery to monastery, or unfurled in nomadic encampments to teach the Dharma.

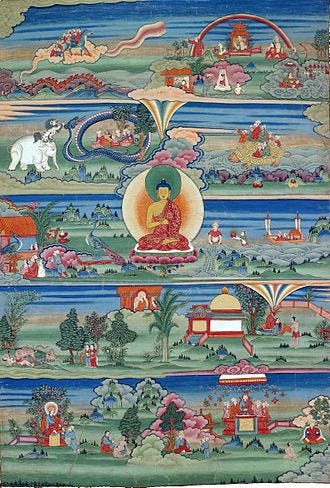

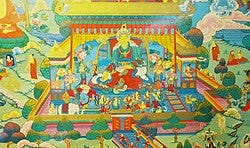

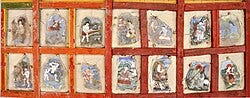

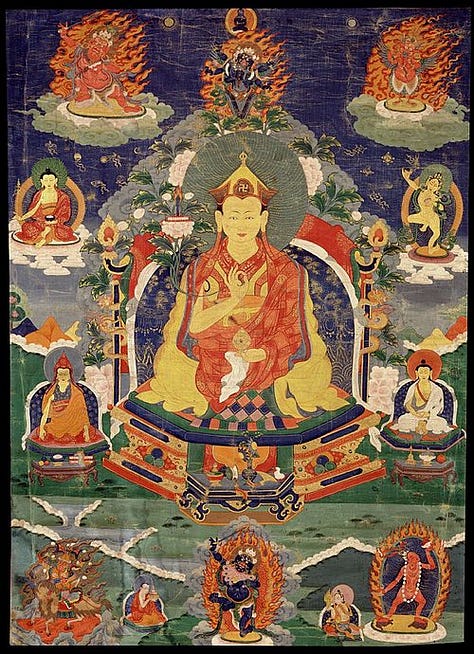

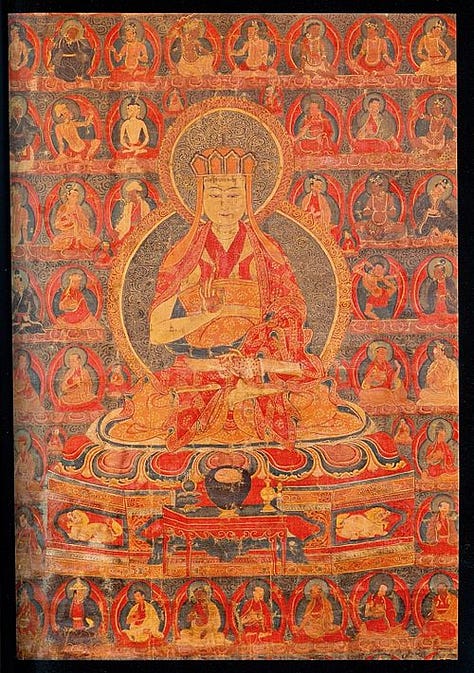

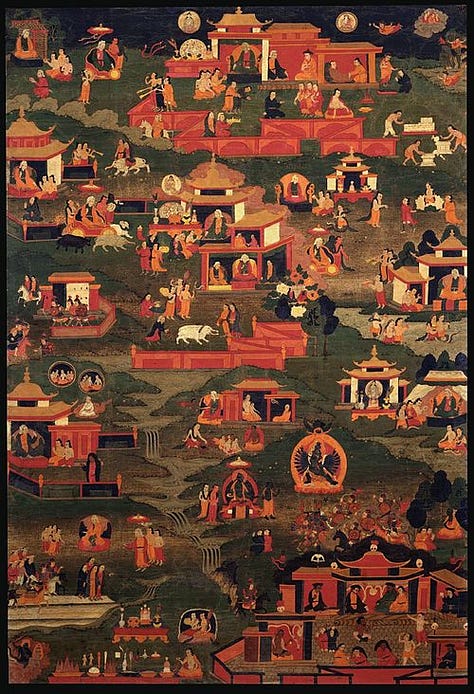

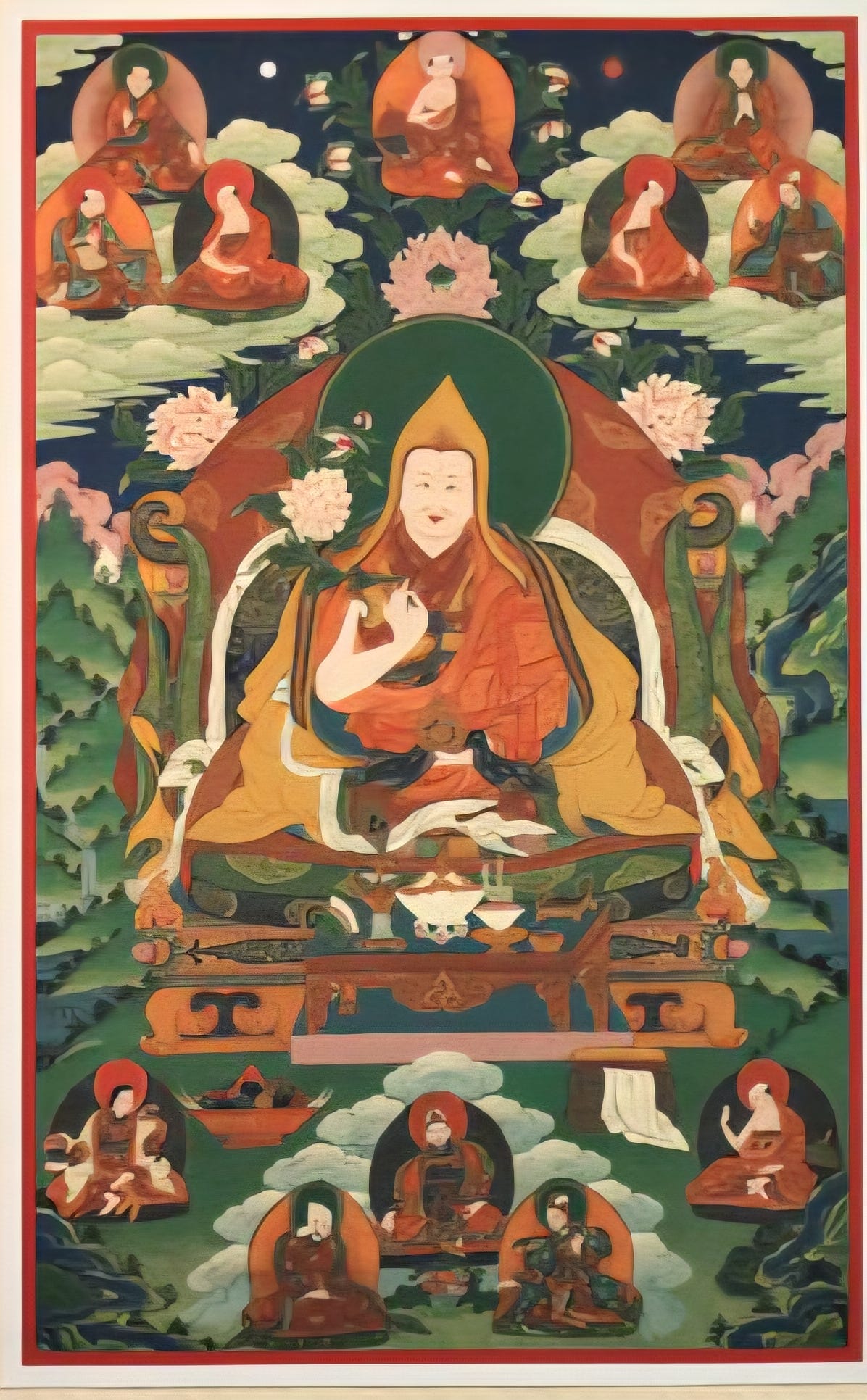

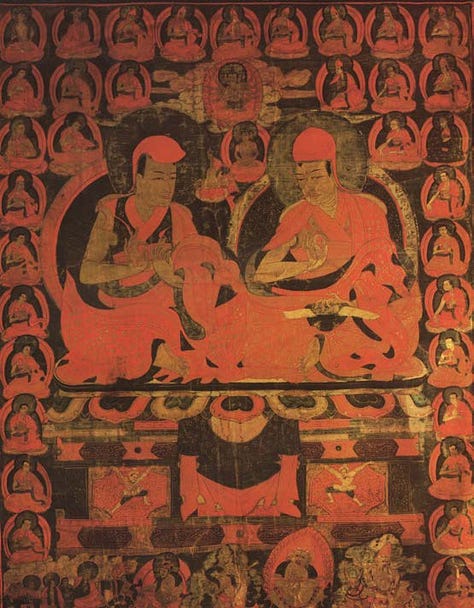

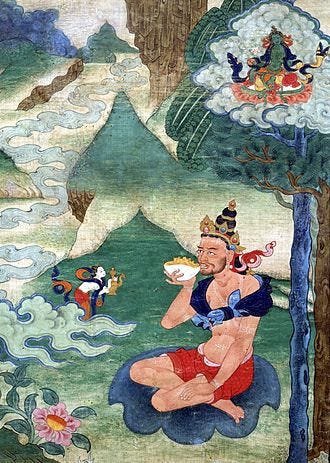

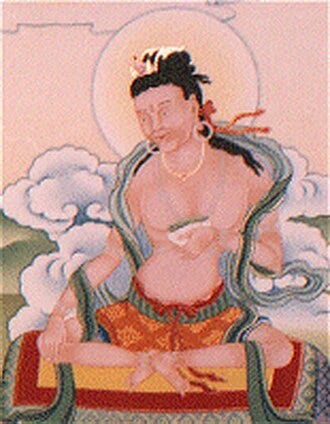

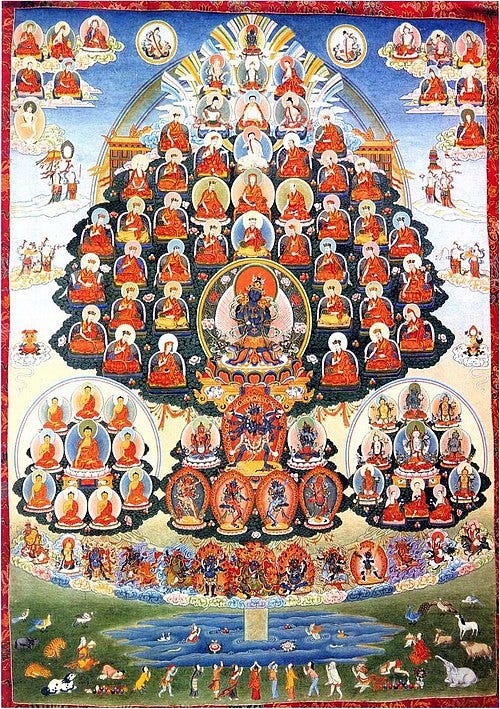

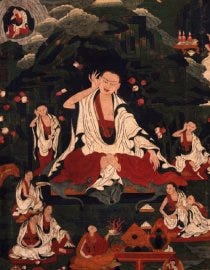

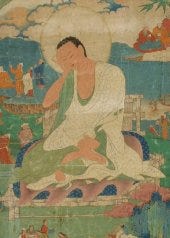

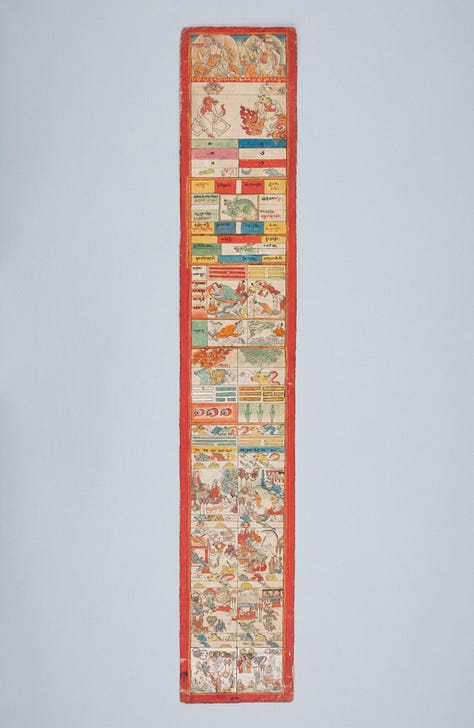

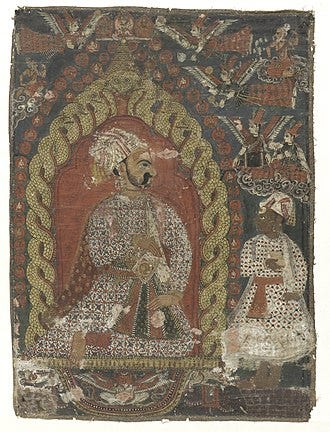

Thangka compositions follow a hierarchical and geometric logic. Typically, the most important figure (a Buddha or deity) is centered and enlarged. Lesser figures, whether lineage teachers, protector deities, or narrative vignettes, appear in diminutive scale around the periphery or above and below the central deity. Symmetry is a guiding principle: deities are often flanked by attendant figures on either side, and registers of smaller figures line the top or bottom. Despite this symmetry, Tibetan thangkas are rarely static; artists enlivened the scenes with billowing scarves, scrolling clouds, and dynamic poses. Repetition of motifs (lotus thrones, aureoles, rocky hills) creates patterned richness. There is also a strong narrative impulse in many thangkas, especially those depicting the life of a saint or the episodes of a sacred story, such paintings contain numerous small scenes connected in an almost comic-strip fashion across the canvas. An excellent example is the life-story thangka set of Milarepa (the renowned yogi poet), which in some versions consists of 19 separate paintings narrating every chapter of his biography. Even a single thangka may encapsulate dozens of episodes in a continuous landscape around the central figure. The ability to integrate a multitude of figures and scenes into a cohesive whole is a hallmark of Tibetan scroll art.

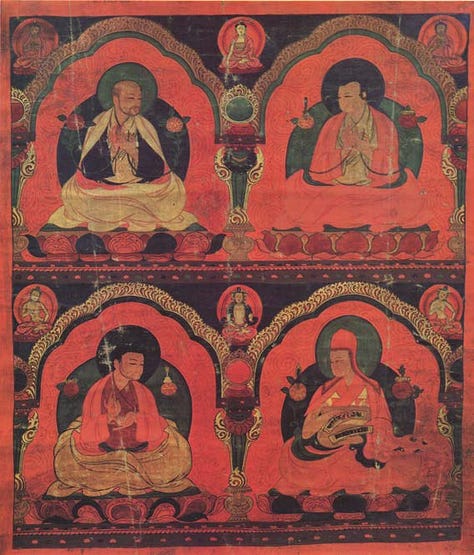

The creation of thangkas traditionally occurred in atelier settings, often associated with monasteries. A master painter (lhadripa) would oversee the overall design and execute the most critical, detailed portions (faces, hands, sacred insignia), while a team of junior artists and apprentices filled in colors and less critical elements. This ensured consistency and allowed large projects (such as multi-thangka sets or huge festival banners) to be completed efficiently. Indeed, rarely is a large thangka the work of a single hand; it is a collective product of a guild of artists. Despite this, individual lineages of painters (and regional styles) did emerge, with masters passing down signature techniques. Some schools, like the Menri and Khyenri styles in central Tibet (15th–16th c.), codified distinctive palettes and brushwork. But all schools adhered to the basic grammar of Tibetan sacred art, where the precision of iconography and the spiritual intent of the image took precedence over personal artistic expression.

In essence, the thangka is both a technical tour-de-force and a spiritual exercise. As one Tibetan thangka master describes, painting a deity is an act of worship: the concentration and ritual involved infuse the image with sacred power. When completed and consecrated, a thangka is believed to host the presence of the depicted enlightened being. The thangka’s portability allowed these blessings to radiate far and wide, hung in temples, nomadic tents, or carried in procession, thangkas became ubiquitous visual ambassadors of Buddhism in Tibet, teaching and inspiring wherever they traveled.

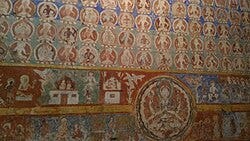

Mandalas (dkyil ‘khor, “center and circumference”) are a cornerstone of Tibetan visual culture, embodying complex cosmology and serving as indispensable tools for meditation and ritual. In Tibetan art, the mandala appears in multiple forms, painted diagrams on cloth, large monastery wall murals, painstakingly constructed sand mandalas, three-dimensional architectural layouts, even small woven or thread constructions. Despite these varied media, all mandalas share a fundamental symbolism: the representation of the universe in its ideal form, a sacred space into which the practitioner imaginatively enters.

At its most basic level, a mandala is a geometric diagram, usually circular in outline, that depicts a palace or blueprint of a deity’s realm. The typical Tibetan mandala is based on Indian Buddhist tantric models (such as those found in the Vajrayana texts transmitted to Tibet around the 8th century), but over time Tibetans elaborated them into highly artful compositions. The structure generally consists of concentric rings (often portraying fire, vajras, lotus petals, and cemeteries or charnel grounds) that surround a square palace with four gates, oriented to the cardinal directions. The central area of the palace contains the principal deity – for example, Buddha Vairochana in the classic Five Dhyani Buddha Mandala, while the surrounding halls and gates house attendant figures and symbolic implements. Every shape, color, and directional placement in a mandala carries meaning. For instance, the palace is square (earth symbol) set within a circle (heaven symbol), illustrating the integration of the material and spiritual realms. The symmetry and balance of the design conveys the underlying order of the cosmos as seen through enlightened eyes. In a Kalachakra mandala, for example, intricate sub-circles map onto elements of cosmology, astrology, and the human subtle body, encoding layers of information in visual form.

Mandalas in Tibetan art serve several functions, they are cosmic maps, meditation devices, and ritual loci all at once. A painted mandala (on canvas or wall) is often used as an aid during initiations (abhisheka): the initiand will visualize themselves entering the mandala’s world, approaching the deity at the center, and thereby receiving blessings. In fact, during elaborate empowerment ceremonies, lamas sometimes create a life-sized three-dimensional mandala out of wood or metal for participants to literally step into, enacting the journey to the enlightened realm. Even when two-dimensional, however, the mandala is understood in three-dimensional terms, practitioners learn to imagine the flat diagram rising up as a divine mansion populated by Buddhas. Thus, the mandala is an “engine of transformation” in Vajrayana practice: by contemplating its ordered universe, one’s own mind is brought from chaos into alignment with enlightened reality. Every detail becomes a focus for meditation, the practitioner visualizes the entire mandala in vivid detail, often “building” it mentally piece by piece, until they can hold the whole complex image in mind. This requires immense concentration and is considered a powerful method of training the mind.

Artistically, Tibetan mandalas are usually distemper on cloth paintings or murals with astonishing precision and complexity. A small mandala thangka (perhaps two or three feet across) might contain hundreds of tiny deity figures in its retinue, each perfectly drawn according to iconographic guidelines. Mandalas are often composed of multiple nested circles filled with geometric motifs – flaming triangles (purifying fire), lotus petals (spiritual rebirth), eight cemetery grounds (transcending death), etc. – each rendered in minute detail. The color schemes are also highly codified; the five Buddha families each have an emblematic color (white, yellow, red, green, blue) assigned to their quadrant of the mandala. For example, an Akshobhya mandala in the east might be predominantly blue, with a blue Buddha at its center, surrounded by symmetrical arrays of deities on lotus seats, all oriented toward the central figure. Tibetan artists became adept at conveying these multi-layered symmetrical layouts without the aid of modern drafting tools, relying on training and sometimes simple compasses/strings to lay out circles. The result are paintings of mesmerizing intricacy that draw the viewer’s eye inward toward the center, a visual metaphor for the mandala’s spiritual function of centering the mind.

Beyond painted mandalas, Tibet is famous for its sand mandalas. In these, monks pour millions of grains of colored sand to create a mandala on a flat surface over the course of days or weeks. Using metal funnels (chakpur) that vibrate to release sand in controlled flows, the monks work concentrically, building the mandala with unbelievable precision. Upon completion, a sand mandala is not preserved; rather it is ritually dismantled, the sand swept together and dispersed (often poured into a river), as an offering to the universe and a profound lesson in impermanence. The ephemeral beauty of the sand mandala highlights a key insight of Buddhism: all compounded things are transient. Still, the creation and destruction of the mandala is believed to bless the environment and beings around with its positive energy.

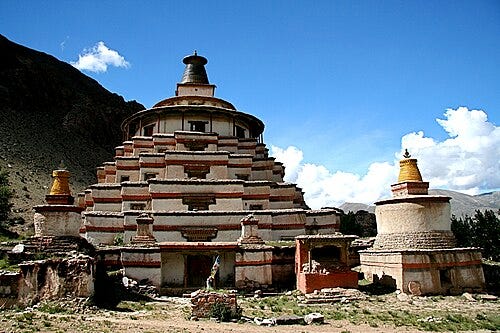

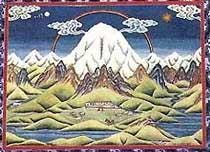

Interestingly, the concept of the mandala extends to Tibetan architecture and sacred geography as well. Entire temple layouts have been conceived as mandalas that one can walk through. The earliest example is Samye Monastery itself, whose design mirrored the ideal Buddhist universe: its central temple (Utse) symbolized Mount Meru, the cosmic mountain, and was surrounded by four temples at cardinal points representing the four continents, with outer walls and gates mapping the outer rings of a mandala. Likewise, the great Kumbum stupa of Gyantse (15th century) is literally a three-dimensional mandala in the form of a nine-tiered stupa. It contains 73 chapels across six floors, arrayed as one ascends, that cumulatively present a complete mandalic pantheon of 20,000 deities. Walking upward through the Kumbum’s spiraling galleries is tantamount to moving toward the enlightened center – an initiation in stone and space. Even the act of circumambulating a stupa or shrine, so integral to Tibetan devotional life, has mandalic significance, one is moving through the sacred geometry of a blessed space. Painted mandalas often adorn the ceilings of assembly halls and the upper walls of sanctums, reinforcing the idea that the monastery itself is encircled by protective and harmonizing forces.

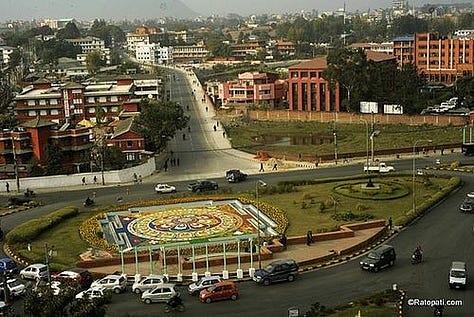

Culturally, mandalas have had broad influence on Tibetan artistic imagination. The motif of circular, radial balance appears in everything from carpet designs to butter sculpture offerings. More profoundly, mandalas provided a framework for Tibetans to interpret their landscape, holy mountains, lakes, and pilgrimage routes were sometimes conceptualized as giant mandalas inhabited by tutelary deities. For instance, the pilgrimage circuit around Mt. Kailash is described in mandalic terms, with Kailash seen as the world-mountain Meru. Thus the mandala principle of an ordered sacred center pervades Tibetan art and architecture at all scales.

In modern times, Tibetan mandalas have captured the global imagination for their beauty and philosophical depth. Depth psychologists like Carl Jung appropriated the mandala as a symbol of wholeness and self-integration. Yet in their original context, mandalas remain living parts of Tibetan spiritual practice, not merely artworks to behold, but sacred maps to enter with body and mind. Whether rendered in paint, sand, or architecture, the Tibetan mandala is a shining example of “sacred geometry”, art as a direct pathway to the transcendent. By engaging with mandalas, devotees are invited to perceive the cosmos not as chaotic or profane, but as an inherently ordered, enlightened realm in which they too can find their center.

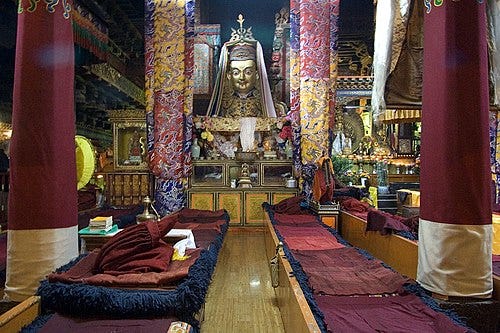

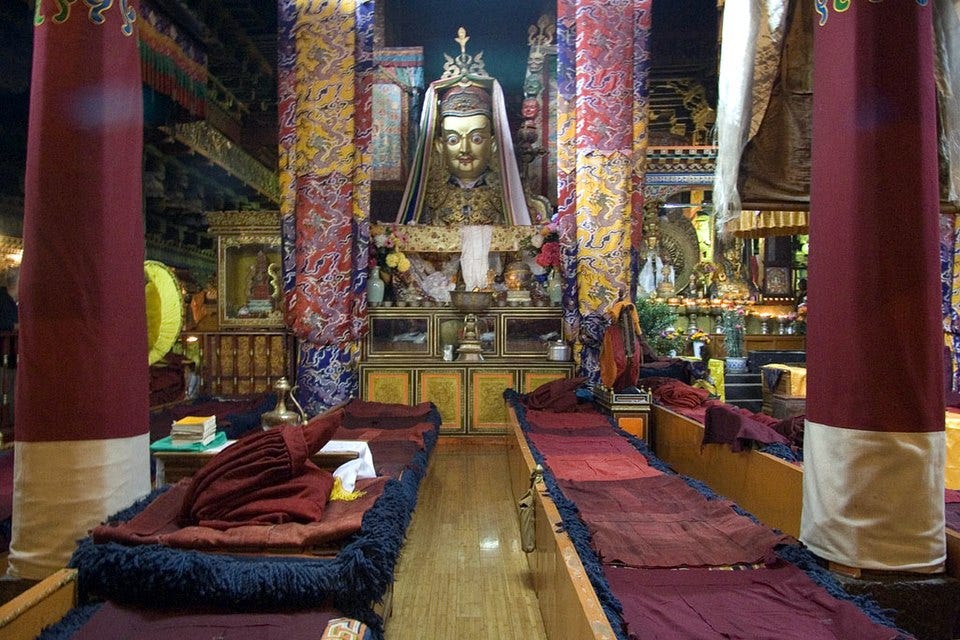

While paintings dazzled with color and detail, sculpture provided Tibetan Buddhism with its most tangible expressions, the three-dimensional forms of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and saints that filled temples and shrines. Tibetan sculpture evolved through a complex interplay of foreign inspiration and local innovation, across media ranging from cast bronze to carved wood and molded clay. Tracing this evolution reveals how Tibetan artisans gradually transformed Indian and Nepalo-Kashmiri models into a distinctly Tibetan sculptural idiom.

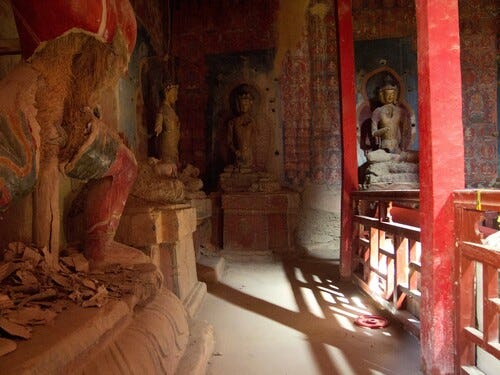

Early Phase (7th–9th centuries): The earliest Buddhist sculptures in Tibet were largely imported or commissioned from abroad. As noted, Songtsen Gampo’s reign saw the arrival of revered statues like the Jowo Shakyamuni (said to have been crafted in India or China) and a Jowo Mikyö Dorje (Maitreya) brought by the Nepali princess. Additionally, Newar artists from the Kathmandu Valley were invited to decorate the first temples. Carvings in the Jokhang temple, such as wooden door lintels and roof struts, depict Buddhist and Hindu themes in a style “noticeably similar to sculpture in Nepal” of that era. These works reflect the Licchavi/Newar aesthetic (sensuous, smooth-bodied figures with elegant tribhanga poses and refined facial features) which itself was rooted in Gupta North Indian art. It’s clear Tibet “sought the very best artists” for these sacred commissions and found them among the master craftsmen of the Himalayas. An early Tibetan chronicle even claims that the Jokhang was originally built to house a single Nepalese-made copper image of the Buddha, the one brought by Queen Bhrikuti, underscoring Nepal’s seminal role in Tibet’s sculptural tradition. By the mid-9th century, however, the suppression of Buddhism under King Langdarma and ensuing political fragmentation led to a near halt in religious art patronage. Many early sculptures and casting workshops likely perished in that dark period (ca. 842–978 CE), leaving few tangible artifacts from Tibet’s first Buddhist age.

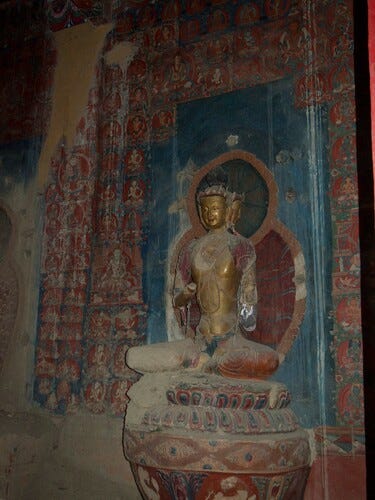

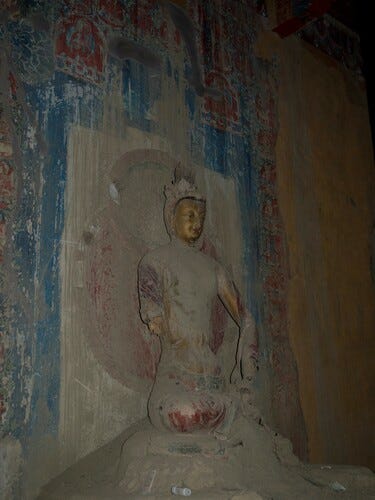

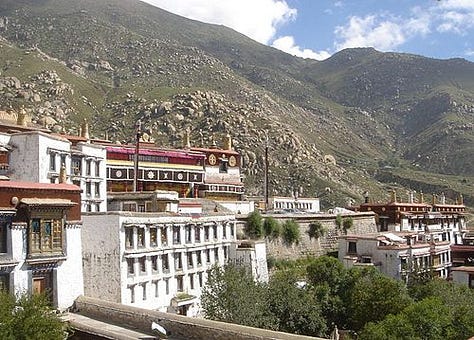

A great revival of Buddhist art, often called the “Second Diffusion” of Buddhism in Tibet, began in the late 10th century, spearheaded by kings of western Tibet (Guge and related kingdoms) like Yeshe-Ö. These rulers and monks such as the translator Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055) energetically re-engaged with the Indian Buddhist heartland, traveling to Kashmir and the Gangetic plains to obtain texts, teachers, and art. The result was a renaissance of Tibetan sculpture, fueled by imported talent. It is recorded that Yeshe-Ö “invited artists and Buddhist scholars to bring Buddhist art to Toling” (the royal monastery) and that Rinchen Zangpo returned from Kashmir accompanied by 32 Kashmiri artists, who together embellished the new temples of Guge with paintings and sculptures. The influence of Kashmiri aesthetics at Guge is well documented; the clay statues and wall paintings in Toling and Tsaparang display the elongated bodies, refined almond eyes, and elaborate Indian jewelry characteristic of Kashmir’s art. For example, statues of Buddha Vairochana and attendant bodhisattvas in the Toling stupa have the slender waists and high, pointed chins of Kashmiri style, with lavish gold crowns and profuse ornaments; the painted goddesses have the “elongated eye” outlined in black as if in Kashmiri kohl makeup. Yet these same figures also manifest subtle adaptations to Tibetan taste; slightly more robust physiques and an emphasis on an awe-inspiring presence over sensual elegance. This suggests that even as Tibetan patrons emulated Kashmiri and Indian styles, they directed artists to infuse the images with a greater sense of spiritual power (wangthang in Tibetan) befitting local devotions.

During this era, hundreds of bronze images were also imported or commissioned. Indian sources tell of monumental metal statues at Bodh Gaya and in Kashmir that Tibetan pilgrims would have seen and aspired to replicate. Tibetan texts indeed credit Atīśa (an Indian master who taught in Tibet 1042–1054) with bringing finely crafted bronzes and ordering others from India for Tibetan temples. We also know that many Pāla-period bronzes from Northeastern India (8th–12th c.) found their way into Tibet during or after the 12th century, either through gift, purchase, or as refugees from Muslim invasions. These Pāla-style bronzes (usually gilded copper alloy statues of Buddhas and Taras) with their sensuously modeled forms and ornate details became cherished models for Tibetan metalworkers. Likewise, Nepalese bronze casters, famous for their lost-wax casting skill, were in demand; Tibetan chronicles note a continuous flow of Newar casters and sculptors into central Tibet, where “there was no convent at its foundation or prosperity that was not embellished by [Newars] with statues or frescoes” during the 11th–14th centuries. The collective result of these influences is evident in what’s called the “Indo-Nepalese” style of early Tibetan sculpture: elegant, symmetric figures with a high level of craftsmanship, often indistinguishable from contemporaneous works made in Nepal or Eastern India. A fine example is a 11th-century gilt bronze Avalokiteshvara in Tibetan possession (likely made by a Kashmiri or Newar artist), which bears all the hallmarks of Pāla art, a lithe torso, refined facial expression, and delicately incised patterns on the crown, yet radiates a devotional intensity prized by Tibetans.

By the 13th century, Tibet had begun to develop a more indigenous sculptural idiom, even as foreign artisans remained influential. Three factors contributed to this: the wide dissemination of craft knowledge (local Tibetans training under Indian/Newar masters), the patronage of new Tibetan Buddhist schools (Sakya, Kagyu, etc.) with their own aesthetic preferences, and a gradual shift in taste towards more forceful, expressive images. Tibetan-made sculptures started to exhibit slightly broader faces and more powerfully built physiques than their Indian predecessors, perhaps reflecting Central Tibetan ideals of beauty and the influence of robust indigenous physiognomies. There was also a conscious effort to emphasize the spiritual presence or charisma of the figures, sometimes at the expense of the refined sensuality seen in earlier Indian/Nepalese art. In other words, a Buddha image crafted in 14th-century Lhasa might look a bit stiffer or more formal than an 11th-century Pāla bronze, but Tibetans valued it for conveying a numinous authority.

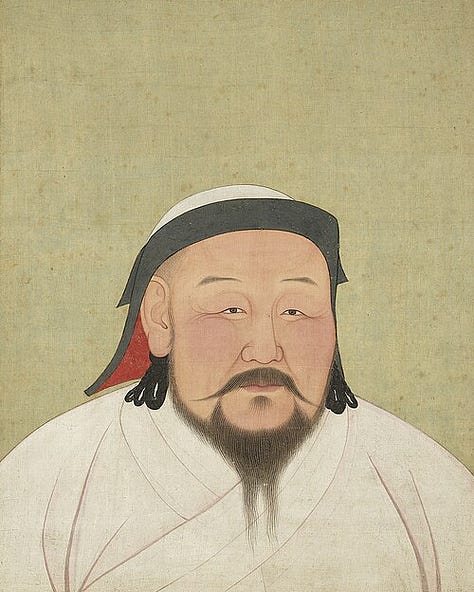

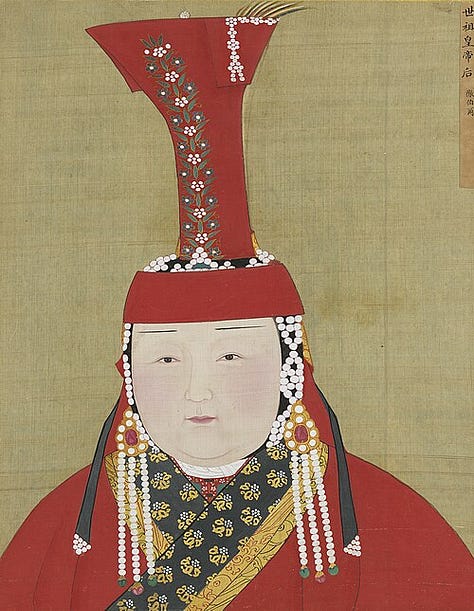

It’s during the 13th–15th centuries that we see regional workshops and styles flourish within Tibet. For example, under Sakya patronage in the 13th century (with Mongol Yuan dynasty support), a great number of Newar artists worked in Central Tibet, creating a fusion style sometimes termed “Sakyapa style.” Sakya-period bronzes and murals are marked by extremely elaborate decorative elements (lotus scrolls, makara-headed arches, etc.) and a preference for rich ornamentation on almost every surface. These features, clearly derived from Newar aesthetics, became part of the Tibetan repertoire. Monasteries like Shalu and Gyantse in the 14th–15th centuries employed artists from both Nepal and China, resulting in sculptures that sometimes mix Chinese naturalism (e.g. in facial features or robe drapery) with Nepali-style idealism. Bronze statues from the Gyantse workshops (commissioned by the princes of Gyantse in the 1400s) often have slightly more pronounced torsos and a stern gaze, an assertive Tibetan character, even as they retain Newar technical finesse and Chinese-influenced decorative flourishes (like gilded dragons on bases). By late 15th century, scholars can identify a truly Tibetan sculptural style emerging; one that still nods to its Indian/Newar origins in iconography and casting methods, but presents figures with a unique gravity and vigor.

Throughout these developments, Tibetan sculptors worked in several media: chiefly metal (bronze/brass), clay, and wood, each serving different purposes. Lost-wax casting in copper alloy was the preeminent technique for portable images and high-status icons. Many Tibetan metal sculptures were gilded – fire-gilding with mercury amalgam – to give them a lustrous gold surface, symbolizing the incorruptible, radiant nature of enlightenment. Gems like turquoise and coral were inlaid in crowns and jewelry on the statues, a practice adopted from Nepal. Clay (and stucco) was predominantly used for monumental statues within temples; for example, the enormous 8-meter clay Maitreya at Tholing, or the various life-size deity statues lining chapel walls in central Tibet. Clay figures were built on armatures of wood and straw, then painted and often gilded once dry. These allowed for expressive, large-scale creations at relatively lower cost than metal; however, they are more fragile and many have not survived Tibet’s tumultuous recent history. Wood carving was somewhat less common for freestanding statues (except in outlying regions with forest resources, like parts of Kham), but wood was widely used for relief carvings, architectural sculptures, and ritual masks. A few delicate early wood statues (perhaps one or two surviving 11th-century bodhisattvas) indicate that wood carving of deities did occur. Stone carving was rare except for inscribed stelae or rock-reliefs (and those ancient pre-Buddhist rock carvings of animals by Bönpos).

By the 17th–18th centuries (beyond the scope of early monastic orders but worth noting), Tibetan sculpture became more internally organized with hereditary guilds of artists, often Tibetan families of Newar descent, who guarded casting secrets and trained apprentices. The 17th century saw master casters like the Choying Gyatso family in Central Tibet and the ateliers supported by the 5th Dalai Lama producing thousands of gilt bronzes. But even earlier, by the 15th century, certain names like Menla Dondrub (a famed 15th-c. artist) were associated with specific stylistic schools. Yet, most works remain anonymous; the focus was on faithful rendering of sacred forms rather than individual creativity or signature.

To sum up, Tibetan sculpture’s evolution reflects a journey from external inspiration to internal mastery. Early Tibet imported its images and styles from India and Nepal wholesale; by the high classical period, Tibetans had absorbed these influences and given them a new vitality, emphasizing spiritual presence, symmetrical power, and at times a grand, hieratic quality. A Western viewer might sense that Tibetan statues, especially later ones, look more frontal and less sensuous than Indian ones, and indeed Tibetans consciously valued devotional gravitas. As scholar David Weldon observes, a Tibetan-made Buddha may be “not as refined as its eastern Indian precursor, but it is nevertheless imbued with a strong spiritual presence,” prioritizing numinous quality over sensuous form. The continuing role of foreign artisans (Newar, Kashmiri, Chinese) ensured technical excellence remained high, while Tibetan patrons’ tastes ensured the art became more and more “Tibetan” in spirit. By the time the great monastery complexes arose (14th–15th c.), Tibetan sculptors could create massive gilded images of consummate artistry, such as the 15-meter Maitreya in Tashi Lhunpo Monastery (built 1460s), works that astonished all who saw them and stood as proud embodiments of Tibetan faith. The legacy of those developments endures in the countless bronzes and statues preserved in collections and monasteries today, each one a blend of pan-Asian skill and distinctly Tibetan piety.

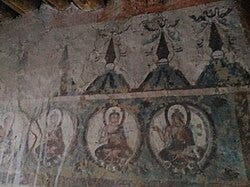

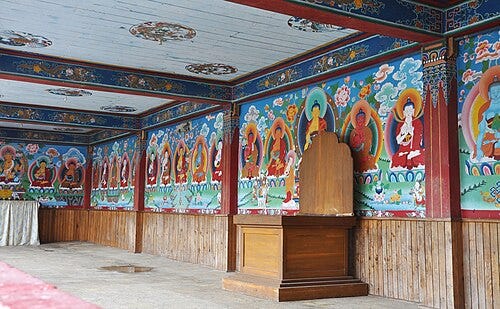

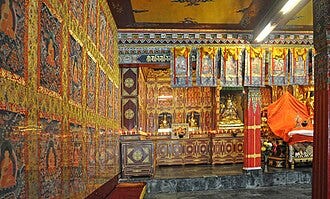

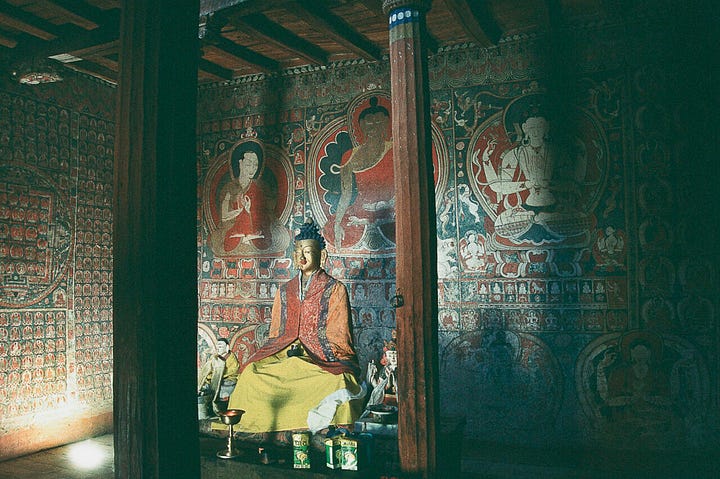

The interiors of Tibetan monasteries are alive with color and storytelling, thanks to the tradition of wall murals that cover temple walls from floor to ceiling. These murals (fresco or secco on plastered walls) serve not merely as decoration but as visual scriptures and chronicles, teaching the Dharma and commemorating history in vivid pictorial form. From the earliest period of Tibetan Buddhism, mural painting has been an integral part of temple construction, Songtsen Gampo’s 7th-century temples reportedly featured painted walls executed by foreign artists. Over time, mural art evolved in content and style, reaching peaks of grandeur in different eras and regions.

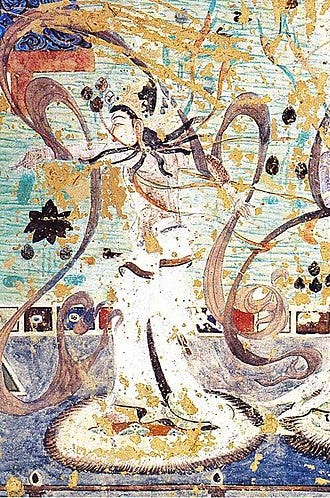

Unfortunately, very few murals survive from the initial diffusion (7th–9th centuries) due to destruction and renovation. However, literary sources and some extant fragments give clues. In the Jokhang and Ramoche temples (7th c.), it is said that artists from Nepal and China painted images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas on the walls. These early murals likely showed Indian Pāla-style influences (idealized, delicately shaded figures) and Newar decorative details, as hinted by later recollections. Interestingly, a Tibetan account claims that Songtsen Gampo himself ordered a Newar artisan to carve and paint four Buddha images on a rock face after seeing a vision, arguably Tibet’s first mural and rock sculpture combination. The style of this period’s painting is described as having “chubby” figures in simple colors, comparable to contemporaneous Dunhuang murals of the early Tang dynasty. We also have the unique case of Tibetan-painted caves at Dunhuang (in Chinese Turkestan) from the 9th century, which show a mix of Chinese and Tibetan aesthetics and may reflect what central Tibetan art looked like before the hiatus.

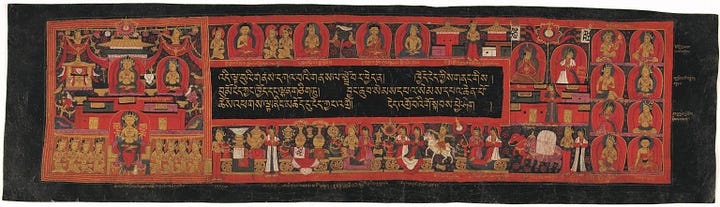

With the resurgence of Buddhism in the 10th–11th centuries, mural painting truly blossomed. In western Tibet (Guge, Ladakh, Spiti), magnificent early murals survive, e.g., in Tabo (996 CE, technically now in India but under western Tibetan influence), Alchi (Ladakh, 11th–13th c.), and Tsaparang (Guge, 15th c.). These display a fusion of Kashmiri and Indian Pāla styles with Tibetan themes. By the 11th–12th centuries, murals evolved into grand narrative cycles and complex cosmological diagrams, far more elaborate than the presumably simple early icons. Murals became “picture-story books” sprawling across temple corridors. They served didactic purposes: to educate monks and layfolk about the Buddha’s life, past-life Jātaka tales, and the great teachings, as well as to inspire devotion through depictions of pure lands and mandalas.

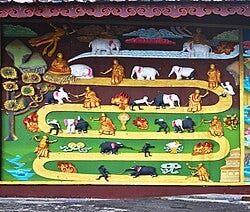

For example, in many monasteries one finds a Life of the Buddha mural series, sequential panels or a continuous narrative frieze showing Prince Siddhartha’s birth, enlightenment, teaching, and mahāparinirvāṇa. Another common subject is the Jataka tales (550 past lives of the Buddha), which are moral fables often illustrated in a comic-strip manner along the base of shrine room walls. These narrative murals enabled even an illiterate nomad to visually absorb the Dharma stories while circumambulating the temple, effectively making the walls into a graphic novel of Buddhism. Murals also frequently depicted the founding legends of the temple or local protector deities, thereby weaving the site’s identity into a sacred story.

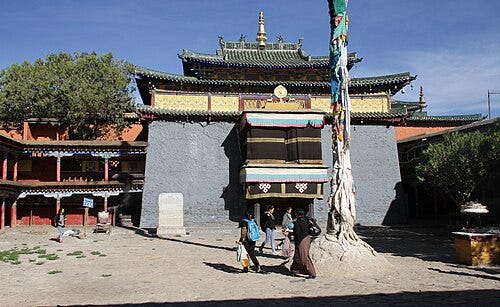

In this period, the Sakya school’s stronghold at Sakya Monastery (founded 13th c.) became renowned for its extensive murals, including lineage thangka-like depictions and perhaps historical scenes. Likewise, at Shalu Monastery (rebuilt 14th c. by Butön Rinchen Drup), a unique fusion style emerged: Butön brought in Nepali and Chinese artists, resulting in murals that combined Nepali figurative elegance with Chinese-influenced naturalism (e.g., freehand drawn garment folds, peony flower motifs). These Shalu murals (some depicting Arhat saints and mandalas) are among the oldest in situ paintings in central Tibet. The early wall paintings at Gyantse’s Pelkhor Chöde (c. 1420) likewise represent a high point: in its Kumbum stupa’s 73 chapels, one finds a nearly complete painted pantheon of deities, all executed in exquisite detail. The Gyantse murals blend Nepali line precision with subtle shading and even attempts at perspective in landscapes; a masterwork of the so-called “Nepalese (Sakyapa) style” in Tibet. Themes there range from cosmological mandalas to detailed biographical scenes of famous lamas.

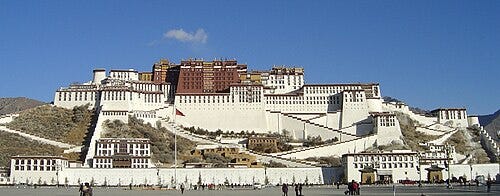

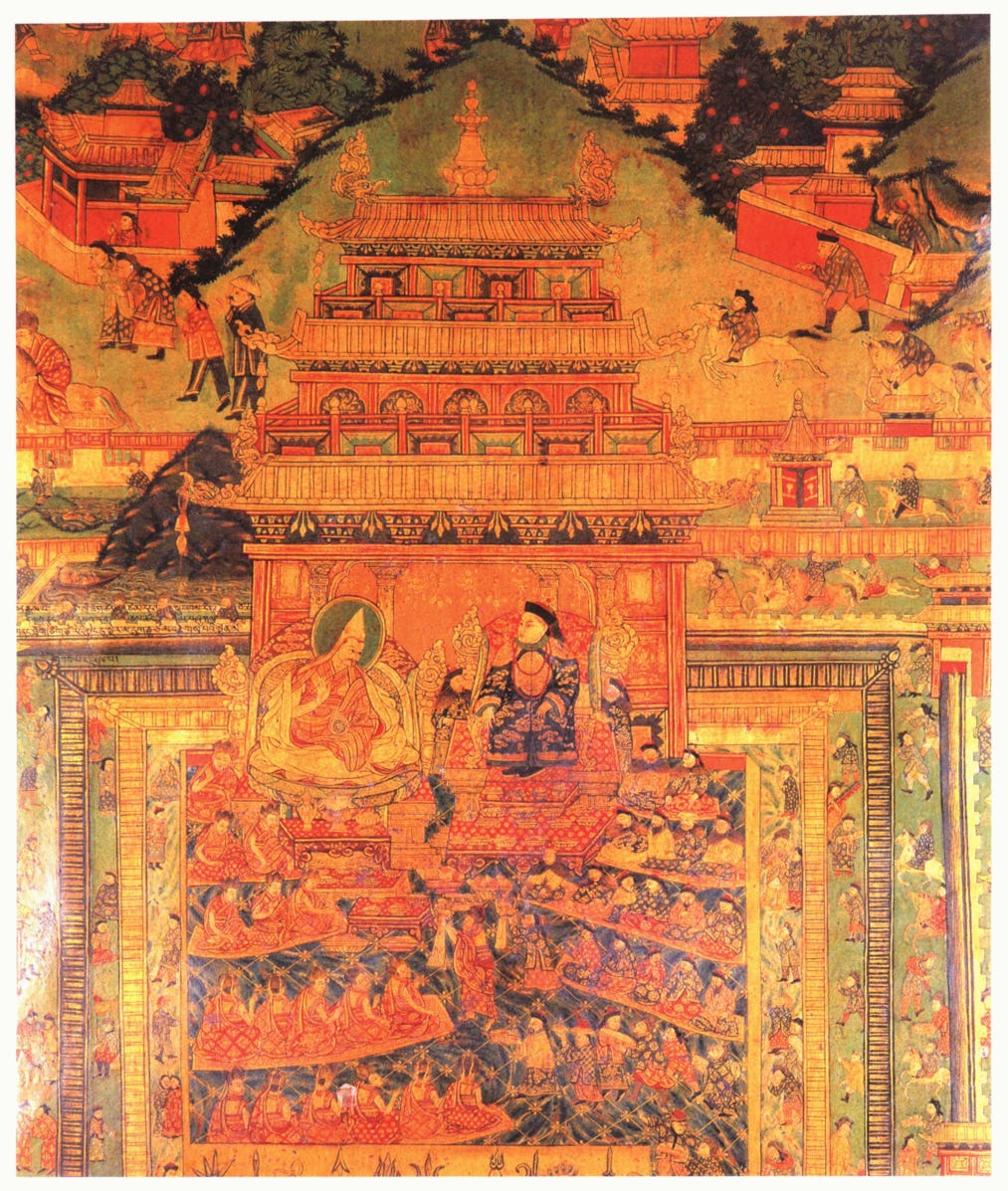

Tibetan art historians often classify murals by subject matter: religious, historical, or social. Religious murals dominate, naturally. These include enormous compositions of Buddhas and mandalas on walls (some temples have an entire wall for a single mandala, used in initiations), portraits of lineage masters and spiritual genealogies, and depictions of ritual scenes like monastic debates, cham dances, or depictions of hells and heavens for moral instruction. A fascinating subset are the lineage tree murals; for instance, in a Kagyu monastery one might see Marpa, Milarepa, Gampopa, and successive Karmapas portrayed in a hierarchical tree, used to affirm the lineage’s authenticity. Historical murals include portraits of Tibetan kings and famous events. The Potala Palace in Lhasa holds classic examples; in the White Palace (secular section) there are extensive 17th-century murals showing the life of the Great 5th Dalai Lama, from his early visions and the civil war to his triumphal visit to China, essentially a visual hagiography and legitimization of his rule. Other historical murals at Potala and Norbulingka (the summer palace) depict Tibetan origin myths (like the monkey ancestor and rock ogress), the building of the Jokhang on the subdued demoness, and scenes of the 13th Dalai Lama’s interactions with modern figures (even meeting foreigners). These served as political statements: as one analysis notes, by the time of the Dalai Lamas, “the state actively commissioned art on a monumental scale, murals, thangkas, sculptures, not merely as devotional works, but as tools of legitimacy, diplomacy, and statecraft,” turning art into a “language of rule.” The storytelling in these murals was carefully curated to present Tibet as a divinely guided realm with rightful leadership.

Social or everyday-life murals are less common but do exist. For instance, the Jokhang contains an 18th-century mural of a festive scene with people singing, dancing, and playing games, a rare glimpse of lay life in art. Samye Monastery too has some amusing murals of acrobats and sports, reflecting perhaps the imperial court entertainments. Such secular or folk scenes added a human touch to monastic walls, though they were usually framed within a spiritual narrative context.

Tibetan muralists used mineral pigments similar to thangka painters, applying them onto dried plaster. Outlines were drawn with charcoal and ink, and larger projects often involved teams working under a master artist’s direction (much like thangka studios). One can often see joins in plaster where the work was divided into sections or patches (especially in big murals on mud brick walls). The style of murals varies by era: earlier ones have clean, deliberate outlines and a flat decorative quality influenced by Indian and Nepalese conventions; later ones (17th–18th c.) may incorporate more shading and even some Western-influenced chiaroscuro, as seen in the New Menri style fostered by the 18th-century master Situ Panchen. But overall, a unifying feature is clarity of line and detail: Tibetan murals can be “read” easily, with important figures enlarged and minor details painstakingly filled in but never so as to confuse the scene. Artists often included Tibetan labels in gold or black ink beneath figures, identifying each character in a lineage or story, which turns the mural into a pedagogical chart. They also followed iconographic guidelines; a deity or teacher should appear with the correct attributes and colors, leaving limited room for artistic license. Yet within these bounds Tibetan muralists showed immense creativity in composing dynamic scenes, balancing crowded action with focal stillness (e.g., a tumultuous battle encircling a calmly meditating Buddha at the center). In important temples, specific courtyards or galleries were dedicated to murals, for example, the Jokhang once had a dedicated mural courtyard, and Tashilhunpo has hallways lined entirely with narrative paintings.

The didactic role of murals cannot be overstated. For many Tibetans, these painted walls were “the Tibetan history books” and “visual Dharma.” A pilgrim visiting the Potala would learn the saga of the Great Fifth; a young monk walking the perimeter of a Dukhang (assembly hall) could absorb the Jataka tales or the iconography of the mandala painted there, effectively studying by sight. In an oral culture, murals reinforced teachings and legitimized lineages by showing the unbroken visual line of transmission. They also acted as mnemonic devices for storytellers and monks giving discourses.

In summary, Tibetan monastery murals transformed bare walls into immersive pedagogical panoramas. From the quiet inner sanctum image of a Buddha attended by bodhisattvas, to the outer corridor thronged with scenes of demons, heroes, and everyman, these paintings engaged all levels of viewers. Over the centuries, they mirrored Tibet’s religious focus (first mainly peaceful Buddhas, later more fierce tantric subjects as those teachings spread), and even its political shifts (e.g., inclusion of Mongol patrons or Chinese emperors in historical murals during periods of patronage). The genius of Tibetan muralists was their ability to condense vast textual and oral traditions into compelling visual narratives, thus walls became as instructive as scriptures. Standing in an old Tibetan temple surrounded by 360 degrees of murals, one is essentially inside a mandala of stories and symbols meant to transform one’s understanding. Even centuries later, faded and smoke-stained, these murals speak: of compassion and wisdom, of history and myth, of the very worldview that underlies Tibetan Buddhist civilization.

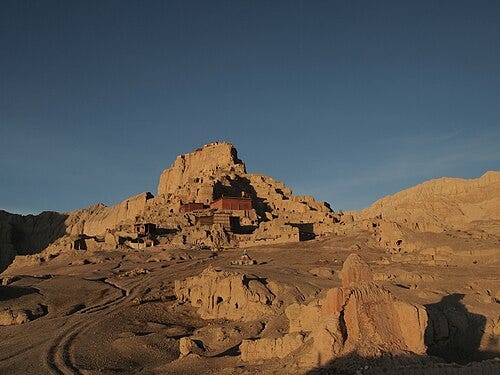

Among the most fascinating chapters in Tibetan art history is the efflorescence of art in the Guge Kingdom of western Tibet and its environs (c. 10th–17th centuries). Guge, now known largely through the ruins of its citadel Tsaparang and nearby monasteries like Tholing, was a cradle of the Second Diffusion of Buddhism and a meeting point of Indian, Kashmiri, and Tibetan artistic currents. Though politically a “lost kingdom” (it fell in the 17th century and was abandoned), Guge’s artistic legacy profoundly influenced greater Tibet, and its surviving artworks are considered among the great treasures of Himalayan art.

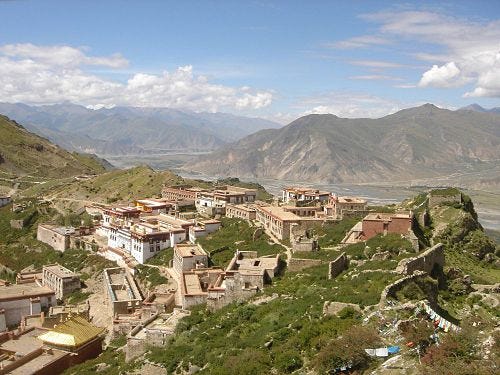

The kingdom of Guge was founded in the far west of the Tibetan plateau (Ngari region) after the collapse of the central Tibetan empire in the 9th century. The early Guge rulers, notably King Yeshe-Ö (also called Lha Lama Yeshe Ö) in the late 10th century, were devout Buddhists who made it their mission to re-establish Buddhism in Tibet. Yeshe-Ö famously sponsored 21 young Tibetans to go to India to study Buddhism, only Rinchen Zangpo survived the journey, and invited Indian pandits and artisans to his kingdom. Tholing Monastery (est. 997 CE) became the royal chapel and a hub of artistic creation. Later, in the 11th century, Guge also welcomed the great Indian master Atīśa on his way to central Tibet. These efforts earned Guge renown as a beacon of Buddhist revival.

The art of Guge is characterized by a brilliant synthesis of foreign styles, especially Kashmiri and northeastern Indian (Pāla), with a nascent Tibetan aesthetic. In the first phase (c. 10th–11th c.), Rinchen Zangpo’s entourage of Kashmiri artists set the tone. They decorated Toling’s temples and stupas with murals and clay statues exhibiting superior craftsmanship and lush detail. The Tsaparang citadel, Guge’s later capital, houses two main temples (the White Temple and Red Temple) which preserve phenomenal examples of this art. The murals in these temples depict Buddhas, bodhisattvas, tantric deities, and great lamas with a level of delicacy and refinement rivaling the best Indian miniatures; the figures have sinuous forms, elegant hand gestures, and intricately patterned silk garments. The color palette is vibrant, azure blues, rich reds, emerald greens, often thickly applied to achieve an opaque, lustrous finish. Artists at Guge showed mastery of chromatic modeling: shading figures to impart volume, e.g. subtle highlighting on cheeks and limbs to suggest roundness. They also made liberal use of gold in both paintings and sculptures. Amy Heller notes how on one standing Buddha statue at Toling, the artists used local gold leaf to gild parts of the figure, giving it a radiant opulence. The effect is that Guge art glows, literally through its gold and bright colors, and figuratively through its imaginative vigor.

What truly distinguishes the Guge style is its blend of realism and ornamentation. On one hand, certain faces in Guge murals (especially subsidiary figures like goddesses) have a gentle naturalism, elongated eyes with thick eyeliner-like outlines, slight smiles, and postures in three-quarter view features that betray the Kashmiri stylistic influence. On the other hand, everything is ornamented to a high degree; thrones are supported by carved lions and makaras; aureoles are edged in scrolling vines; backgrounds are filled with densely packed floral scrolls and mythical creatures in the Nepali fashion. In the Tsaparang Red Temple murals, nearly every empty space is animated by fine scrollwork or tiny attendant figures, creating a tapestry-like richness. Yet the composition remains balanced, a testament to the artists’ skill in handling detail without losing overall harmony. Jeff Watt, curator at Himalayan Art Resources, remarked that the quality of color, composition, and imagination in the Tsaparang paintings stands “among the most beautiful works ever created in this region of the world”.

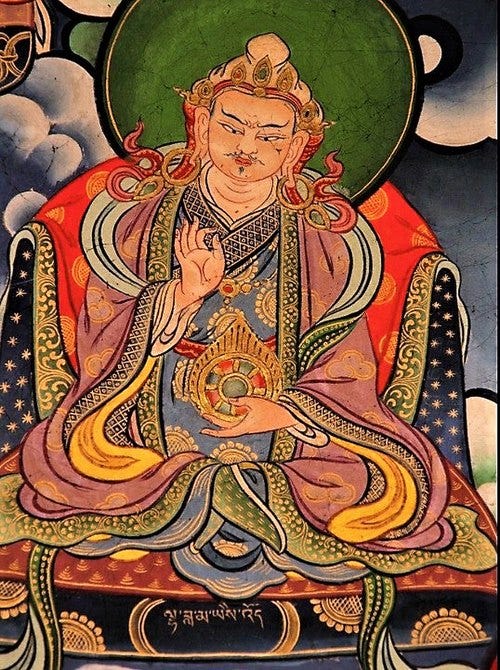

The subject matter of Guge’s art was aligned with the Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism practiced by its royals. Many murals illustrate tantric mandalas and yidam deities central to the New Translation schools (Sarma) that were taking root; such as Kalachakra, Hevajra, and Vajradhatu mandalas. Indeed, the stupa at Toling was decorated with an iconographic program focused on Buddha Vairochana and the Vajradhatu mandala deities, reflecting ritual texts translated by Rinchen Zangpo and popular in the 11th century. At Tsaparang, one finds mural cycles of the Thousand Buddhas, the 35 Confessional Buddhas, and Eight Great Bodhisattvas, indicating the influence of classic Mahayana themes. Historical figures like Lotus-born Guru Padmasambhava and Atisha also appear, linking Guge’s revival to earlier Buddhist heroes. Notably, one mural at Tholing even depicts King Yeshe-Ö and his translator-lama Rinchen Zangpo themselves, paying homage to a Buddha; a rare case of patron portraits, which underscores the conscious legacy-building in Guge’s art.

Although remote, Guge’s innovations did not remain isolated. Through the network of scholarly and marital ties, Guge art influenced central and southern Tibetan regions. Rinchen Zangpo is said to have founded or inspired 108 monasteries across western Tibet, Ladakh, and adjacent areas, seeding the Kashmiri-influenced style widely. The murals at Alchi Monastery in Ladakh, which tradition connects to Rinchen Zangpo’s Kashmiri artists, bear striking resemblance to Guge’s, and Alchi’s fame in art history attests to that style’s brilliance. These western styles likely informed the later “Beri” style of central Tibetan painting (14th c.), which also prized fine line and rich detail. Moreover, Nepali artisans traveling to Tibet often passed through or worked in Guge; one famous artist, Aniko (Araniko) from Nepal, built a stupa in Central Tibet in 1260 before heading to Kublai Khan’s court. We know Nepali artists in that era continuously refreshed Tibetan art all over, and Guge would have been a major early conduit for the Nepali (and indirectly Pāla) styles, helping transplant them into the Tibetan heartland. Thus, Guge’s legacy includes being a bridge of styles; the place where Indian, Kashmiri, and Nepalese art were distilled and then carried eastward.

Guge maintained a high standard of art into the 15th–17th centuries (the updated styles at Tsaparang date to this later era, reflecting some Central Tibetan influence back-flowing in). However, in 1630s, Guge was embroiled in conflict,.its last king, a convert to Christianity named Tri Tashi Gragpa (per Jesuit records), was overthrown amid internal strife and Ladakhi invasion. The kingdom fell and was largely abandoned. Many artworks were lost or defaced over time; the remaining murals suffered from centuries of neglect and more recently from exposure and even Cultural Revolution damage. Yet explorers like Giuseppe Tucci in the 1930s documented much of Tsaparang’s art, and ongoing efforts by conservationists (and digital projects) preserve its memory.

Today, the shattered clay idols and faded pigments on crumbling Guge walls still evoke an artistic golden age. Guge’s significance lies not only in the incomparable beauty of what remains, but in its role as artistic crucible: it proved that Tibetans and foreign artists could together create a new visual language for Buddhism in Tibet, one that would radiate across the plateau. Tibet’s own art “Golden Age” in later centuries built upon the foundation that Guge helped establish. In the remote silence of Tsaparang’s caves, one can still sense that creative spark, a fusion of cosmopolitan artistry with fervent Tibetan piety, which ignited the flowering of Tibetan Buddhist art thereafter.

Before Buddhism took root, Tibet had its own spiritual and artistic heritage, broadly associated with the indigenous Bön religion. Exploring Bön art is essential to understanding Tibetan art’s complete picture, as it provides context for many symbols and stylistic elements that persisted or were adapted in Buddhist art. Moreover, Bön as a living tradition continued parallel to Buddhism, producing its own art forms that both differ from and overlap with mainstream Tibetan Buddhist art.

The early Tibetan plateau (prior to 7th century) left behind sparse but intriguing artistic evidence, mainly in the form of rock art. Thousands of pictographs and petroglyphs, engravings on rocks, dot Western and Northern Tibet. They depict wild animals (yak, deer, sheep, etc.), hunting scenes, ritual dances, and mythical symbols. Some show stylized anthropomorphic figures possibly representing shamans or deities. Scholars consider these the earliest examples of Bon symbolic art, dating back to the 1st millennium or earlier. For instance, portrayals of wild herbivores and geomantic signs on rocks might relate to Bön (or proto-Bön) ideas of animal spirits and territorial markings. Although these are far from the refined thangkas of later ages, they establish an indigenous visual vocabulary; certain motifs like the sun and moon, the swastika (an ancient Asian auspicious symbol later adopted by Bön as the “yungdrung” emblem), and mountain-like triangular forms appear in this prehistoric art. Such motifs would carry forward into historic Bön and even seep subtly into Buddhist art.

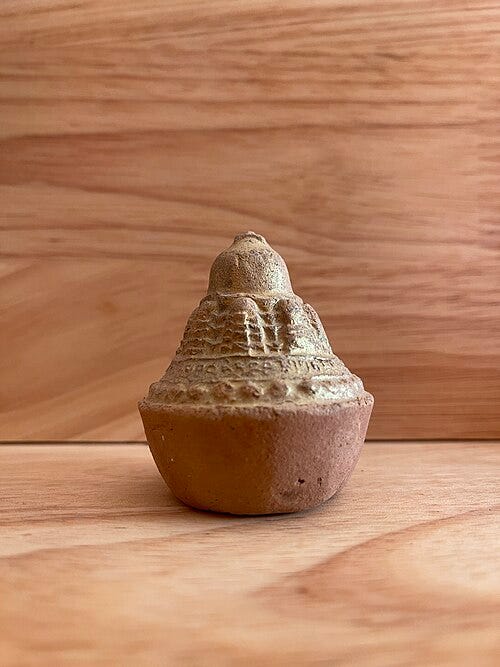

The organized Yungdrung Bön religion (as it calls itself) took shape roughly around the 8th–9th centuries CE, coalescing earlier shamanistic practices into a codified system (with its founder figure, Tonpa Shenrab). Bön posited a cosmos teeming with countless spirits, gods of mountains and lakes, elemental sprites, ancestral deities, which had to be propitiated or subdued through elaborate rituals. This worldview produced distinctive ritual art forms. One was the use of effigies and tschatsa; small votive figurines or tablets. Bönpo shamans created clay figurines (tsa tsa) of local gods or demons to bind or appease them. These tsa-tsas, often inscribed with invocations, are a sort of miniature art that continued into Buddhist usage (where tsa-tsas with Buddhas abound). Another was the crafting of ritual daggers (phurba) and other implements with ferocious imagery to repel evil. Early Bön ritual daggers might feature faces of wrathful deities or animals, setting a precedent for the ubiquitous phurbas in Tibetan Buddhist ceremonies (like those associated with Padmasambhava).

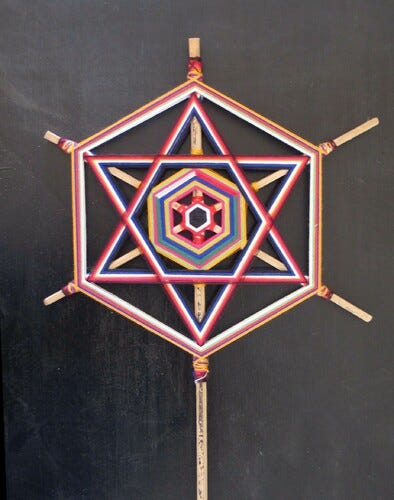

Bön also employed symbolic diagrams in rituals, precursors to mandalas. Often drawn with powders, these diagrams were meant to summon or repel spirits, harmonize elements, or delineate sacred space. They differed from Buddhist mandalas in orientation and purpose (focusing on elemental forces rather than enlightened realms) but conceptually similar as sacred geometry in action. For example, a Bön rite might use a thread-cross mandala (namkha), colored threads wound around sticks, to capture disruptive energies and restore balance. This practice was later incorporated into Buddhist Nyingma rituals as well. Bön’s emphasis on sacred geography also contributed to Tibetan art; holy mountains like Kailash were depicted in abstracted form as the axes of the world. Unlike the realistic landscapes in Chinese art, Tibetan depictions of such mountains (even in Buddhist contexts) remained diagrammatic, encoding metaphysical truths about the site (e.g., four-faced Mount Meru style for Kailash). We can see here how an indigenous way of representing landscape, not as mere scenery but as cosmic maps, laid groundwork for how later Buddhist art would portray geography (for instance, in mandala thangkas or pilgrimage guides).

When Buddhism arrived in Tibet in the 7th century, it did not encounter a blank slate but a thriving Bön/animist culture. The relationship between the two was complex; sometimes hostile (Buddhist legends demonize Bön as black magic), but more often syncretic and mutually influencing. Many early Buddhist temples and images show traces of Bön influence. For example, Tibetan Buddhists appropriated Bön’s local deities by transforming them into Buddhist protectors. The famous story of Padmasambhava subjugating the native spirits and appointing them as guardians of Buddhism (e.g., the great King of Pehar becomes a Dharma-protector) illustrates this. In art, these indigenous deities brought along their visual attributes, armor, fierce animal heads, riding mounts like lions or tigers, which were incorporated into the iconography of wrathful Buddhist deities. Many of the ferocious, scowling dharmapālas in Tibetan Buddhist art (such as the mountain god/local king Tsengo who became a protector) likely have pre-Buddhist origins. The very idea of wearing armor and helmets, seen on certain Buddhist guardian figures, is linked to the martial attire of ancient Tibetan spirit-chiefs and Bön deities.

Symbolically, Bön contributed enduring motifs such as the Snow Lion (a mythic beast symbolizing Tibet), the flaming jewel (treasured in both traditions as symbol of spiritual wealth), and of course the yungdrung (swastika) which is Bön’s primary emblem of eternity. Tibetan Buddhist art does use the swastika motif occasionally as a general auspicious sign, but it is especially prevalent in Bön art, where it appears on crowns, thrones, and as standalone decorative elements. Additionally, some stylistic differences persisted; Bön paintings can feature a slightly asymmetrical composition or unique color schemes not found in mainstream Buddhist thangkas. For instance, Bön sometimes prefers a light blue or white background where Buddhist art might use dark blue. Bön deities also often hold attributes or hand objects that differ from Buddhist ones (like the nine-pointed swastika scepter instead of a vajra, or a feather fan instead of a khatvanga staff), making their thangkas identifiable.

As Buddhism became dominant, however, Bön did not vanish. It adapted by in many cases mirroring Buddhist forms: adopting thangka painting and metal sculpture to depict its own pantheon. Bön iconography includes a full range of figure types analogous to Buddhism’s; Bön has its Enlightened Lord Tonpa Shenrab depicted much like Shakyamuni (often in Buddha-like form or peaceful preaching posture). It has monastic saints and yogis portrayed similarly to Buddhist lamas. It has peaceful deities akin to bodhisattvas and wrathful protectors just as fearsome as Mahākāla. In fact, a casual observer might at first glance mistake a Bön thangka for a Buddhist one, until noticing subtle iconographic cues (like the use of certain hand gestures or specific symbols unique to Bön). For example, a Bön wrathful deity always has a corresponding peaceful form (and totally different name), a paired concept not required in Buddhism. Bön’s four highest deities, the “Four Transcendent Lords” (such as Satrig Ersang, a goddess, and Shenlha Ökar, a light-god akin to Vairocana), are conceptually akin to the Five Dhyani Buddhas of Buddhism, and their depictions overlap in style, yet they are distinguished by Bön symbols like sun-discs, stars, or special hand implements. Bön murals and thangkas also often include annotative text in the Zhang-Zhung or Tibetan script identifying figures, since some look so similar to Buddhist ones that clarity was needed for devotees.

One interesting distinction; Bön art tends to allow more asymmetry in composition. A Buddhist thangka nearly always centers the main figure and arranges retinues symmetrically. Bön thangkas might place the main figure slightly off-center or have an uneven distribution of sub-figures, reflecting a different aesthetic sensibility (though not always; many later Bön thangkas followed Buddhist composition norms to the letter). Another hallmark of Bön paintings is the inclusion of uniquely Bön ritual scenes: for instance, murals of sky burial sites, smoke offering rituals, or treasure vases specific to Bön mythology.

In the cross-pollination between traditions, Buddhism in Tibet also absorbed some Bonpo artistic personnel. Historical records note that in the 11th century, when kings like Langdarma suppressed Buddhism, many Buddhist artists and scholars went underground and even took refuge with Bonpos. Later, Bonpos often hired Newar and Tibetan Buddhist artists to decorate their new monasteries (e.g., Menri and Yungdrung Ling monasteries in 17th-century Amdo), resulting in Bön art that is stylistically very close to Gelugpa art of the same period, except for the different divine figures.

Bön continues as a minority religion in Tibetan regions and in exile, and its artistic production has paralleled Buddhist art’s trajectory. Modern Bonpo thangka painters produce images of Tonpa Shenrab (sometimes in Buddha form with a topknot and monastic robes, other times as a crowned peaceful deity) and complex mandalas for Bonpo deities. Sculptures of Bon protectors, often commissioned in Nepal by Newar artisans, show the protectors on their unique mounts (for example, a Takla Mebar figure riding a flying horse). These contemporary works often deliberately emphasize what is distinct about Bön, such as painting the sky dark green instead of blue, or using the nine-swastika emblem on thangka borders – as a way of asserting Bonpo identity within the broader Tibetan culture.

In summary, the art of Bön provides the hidden foundation of Tibetan visual culture. It preserves the imagery of Tibet’s shamanic past (mountains alive with spirits, primal ferocity and magic) and shows how that imagery was not eradicated by Buddhism but transformed and integrated. Bon art reminds us that Tibetan aesthetics, even in the most refined Buddhist thangka, are rooted in a worldview where every element of nature is alive and sacred. The mountains in a Tibetan painting are not mere backgrounds; they have eyes and spirits, as Bon taught. The fierce deities are not foreign imports; they are the old gods given new names and vows. By understanding Bon and pre-Buddhist art, we gain insight into the Tibetan imagination that underlies all later artistic expression. It is a worldview where the physical and spiritual merge: “mountains speak, wind carries messages from spirits, every stone might hold a deity’s presence”. This sensibility “continues to animate Tibetan aesthetics even in the most refined Buddhist works.” Thus, Tibetan Buddhist art’s classical forms carry in their DNA the legacy of Bön; a testament to Tibet’s unique genius for blending old and new into a continuous sacred art tradition.

By the 17th century, Tibet entered a new era of artistic flourishing under the leadership of the Dalai Lamas, the highest lamas of the Gelug school who became temporal rulers of a unified Tibet. Particularly under the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1617–1682), and later the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso (1876–1933), Tibetan art received significant state patronage and assumed new dimensions of grandeur and complexity. This period saw not only the synthesis of diverse artistic influences into a distinctly “Tibetan” style, but also the use of art as a tool of governance and cultural identity.

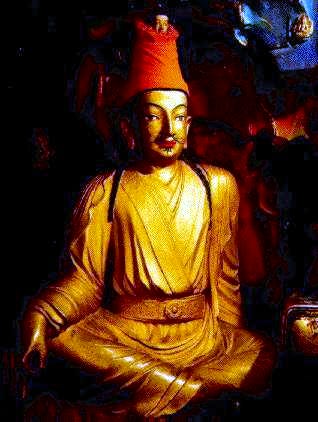

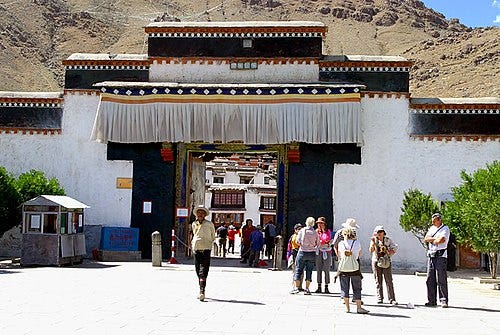

The 5th Dalai Lama is often revered as a great unifier and patron of the arts, earning the moniker “The Great Fifth” for both his political and cultural achievements. After 1642, with the military backing of the Mongol prince Gushri Khan, he established a new Ganden Podrang government and ushered in a renaissance of Tibetan art and architecture to legitimize and glorify his regime. One of his most iconic projects was the construction of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, begun in 1645 on Red Hill. This monumental structure, part fortress, part monastery, part palace, stands to this day as a symbol of Tibetan nationhood. The Potala’s massive white and red walls, tiered chapels, and golden roofs represent a fusion of Tibetan, Nepali, and Chinese architectural elements, yet the overall concept (a multi-story palace named after Avalokiteshvara’s mythical abode, Mount Potalaka) was uniquely Tibetan in ambition. Inside, the 5th Dalai Lama filled it with exquisite art: vast wall murals, thousands of statues, and precious reliquaries. The Potala’s White Palace murals narrate events of his life and the geopolitics of Tibet, effectively state propaganda in pigment. The Red Palace, added after his death by the Regent Sangye Gyatso, enshrines his golden stupa tomb, a towering chorten lavishly decorated with gold and jewels, as well as chapels for all the important divinities of the Gelug pantheon. The scale and opulence of these works were unprecedented. An eyewitness to the Potala in the late 1600s would have seen entire galleries of gold-and-azure paintings depicting the Dalai Lama’s visionary dreams and encounters, life-size statues of Tsongkhapa and the Gelug patriarchs in glistening gilt copper, and massive thankas draping ceremonial halls.

Under the Great Fifth’s patronage, art became a language of rule. He commissioned thangkas and murals that portrayed not only religious scenes but also worldly events like enthronements, diplomatic visits, and the subjugation of enemies, thereby visually reinforcing the idea of the Dalai Lama’s divine mandate to govern. One mural, for instance, shows the Dalai Lama’s famous meeting with the Shunzhi Emperor in Beijing; an event that in reality never occurred (the Dalai Lama stopped short of Beijing), but was painted as if it had, to symbolize the spiritual conquest of China by Tibet’s leader. By curating such imagery, the 5th Dalai Lama forged a narrative of a “divinely guided, legitimate Tibetan state”. This politicization of art did not diminish its spiritual function; rather, it entwined the two. Religious art continued to flourish in quality: the 17th century saw the Menri style of painting reach maturity, blending Newar and Chinese influences into a harmonious Tibetan style (characterized by fine linework, bright mineral colors, and a balance of ornate detail with clear composition). Artists like the great Choying Gyatso (17th c.) were active during this era, painting elegant thangka sets for the Dalai Lama’s court. Sculpture too got a boost; the Great Fifth sponsored the casting of innumerable gilded bronzes, often featuring Yamantaka, Cakrasamvara, and other tantric tutelary deities of the Gelug school, as well as large images of Buddha Maitreya (for example, a colossal Maitreya statue was planned for the Potala but later completed in metal at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery).

One notable project was the creation of giant appliqué thangkas (called thongdrels or gos-sku) for public display at monasteries; a tradition the Fifth encouraged. These enormous silk thangka banners, some the size of a multi-story building, were unveiled during festivals to inspire the masses. It required coordination of tailors, painters, and donors on a grand scale, reflecting how communal devotion under state guidance could yield awe-inspiring art. In short, the 5th Dalai Lama’s era can be seen as a “Classical Period” where Tibetan art, with ample resources and centralized direction, reached an apex of refinement and iconic power.

Fast-forward to the turn of the 20th century; Tibet under the 13th Dalai Lama faced modern threats and began to cautiously modernize. Thubten Gyatso (the 13th) reigned during a tumultuous time; British invasion in 1904, Qing Chinese invasion in 1910, and subsequent independence after 1912. Amid these challenges, he undertook measures to strengthen Tibetan identity and institutions. In the realm of art, the 13th initiated restorations of important monuments, recognizing art’s role in national identity. For instance, after the ravages of the Chinese occupation of Lhasa in 1910-12, he oversaw the refurbishment of temples and the repainting of damaged murals. He also commissioned new works that subtly incorporated modern themes. One remarkable project was a set of murals at the Nechung monastery (the seat of the state oracle) which depicted not only traditional cosmology but also elements of recent history and reform; reportedly even the institution of a modern police force and the introduction of the telegraph, in allegorical form. A scholarly essay notes that the 13th “commissioned murals depicting political reforms” and embraced photography as a medium to document and complement traditional painting. Indeed, he was likely the first Tibetan leader to be photographed extensively, and he allowed photographs to be hung in some contexts where only paintings would have been before. This shows a nascent blending of old and new media.

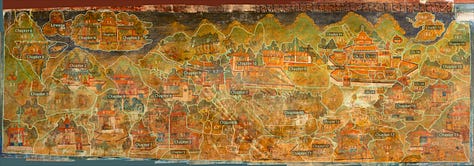

Another example of the 13th’s influence is the “World Mandala” painted in one of his private chambers, which reputedly included a modern world map combined with the Buddhist cosmograph; symbolizing Tibet’s effort to understand its place in a changing world (this is referenced by scholars as an incorporation of modern cosmography into traditional art). The 13th, who had traveled to India and encountered global modernity, collected foreign objects which occasionally found their way into artistic depictions. Under him, thangka painting continued strongly; the late 19th/early 20th century saw masters like Gega Lama and others maintain the lineage of Menri and Gardri styles. But there was also an official interest in documenting via art; he reportedly had a series of paintings made of all the important pilgrimage sites of Tibet, possibly to assert Tibetan cultural heritage in the face of foreign encroachment. These paintings used a traditional panoramic style yet included accurate topographical details and annotations, something like illustrated maps, a unique genre at the intersection of art, geography, and politics.

Thus, the 13th Dalai Lama’s patronage is marked by conservation, subtle innovation, and the first adaptation to modernity. He understood that supporting the arts was supporting the religion and, by extension, Tibetan identity. By the early 20th century, the Lhasa government also established schools (including an art school by Regent Reting in 1920s) to train young Tibetans in traditional arts, ensuring continuity.

Tibetan art under the Dalai Lamas, especially the 5th and 13th, exemplifies how high-level patronage can galvanize artistic production and also steer its messaging. The 5th Dalai Lama’s era produced art on a monumental scale and with integrated symbolism, effectively using visual culture as a unifying force in a theocratic state. The 13th’s era maintained that heritage while cautiously engaging the new world. Between them (and the intervening Dalai Lamas as well, some of whom like the 7th and 8th were notable scholars and possibly arts patrons), they cemented the centrality of Lhasa as Tibet’s artistic heart. Many arts were standardized or codified during their rule (for example, the Tibetan canon of iconometry and iconography was refined in Gelug scholastic texts, studios in Lhasa defined the “official” style to be emulated across Tibet).

In sum, the period of the Dalai Lamas marks the institutional flowering of Tibetan Buddhist art, a time when thrones were flanked by tangka and murals served as both teaching tools and declarations of Tibetan sovereignty. As one commentator put it, by the end of the 13th Dalai Lama’s time “the political role of art was fully institutionalized” in Tibet, every major monastery and palace was not only a spiritual center but also a repository of painting and sculpture affirming the Tibetan Buddhist state’s vision. This legacy continues to inspire, and the works created under these great patrons remain among the most admired treasures of Tibetan culture.