The Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, is widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of early Byzantine art and architecture. Constructed in the mid-6th century CE, this monument exemplifies the intricate fusion of imperial ideology, Christian theology, and innovative design that defined Byzantine culture.

Ravenna, once the capital of the Western Roman Empire and later the administrative center of Byzantine Italy, was a city of strategic, political, and cultural importance. In the 6th century CE, Ravenna stood at the crossroads between the declining Latin West and the burgeoning Byzantine East. Under the auspices of Emperor Justinian I, the Byzantine administration invested in monumental construction projects to reaffirm its authority and to express a renewed vision of imperial grandeur. The Basilica of San Vitale was conceived against this backdrop, reflecting both the political necessity to legitimize Byzantine rule in Italy and the fervent religious devotion of its era (Mango 112; Norwich 85).

Ravenna’s unique position as a melting pot of classical Roman heritage and emerging Eastern influences allowed for an unprecedented synthesis of architectural and artistic traditions. The city’s monuments, including San Vitale, served as visual manifestos that communicated the divine sanction of imperial power. As a center of early Christian culture, Ravenna was also a focal point for theological debates and liturgical innovation, setting the stage for San Vitale’s rich iconographic program (Cormack 89).

San Vitale is celebrated for its innovative architectural plan, which departs from the traditional longitudinal basilica design prevalent in the West. The structure is organized around an irregular octagonal plan crowned by a central dome; a feature that both symbolizes the celestial realm and creates a dynamic spatial experience. This design reflects the Byzantine desire to create a microcosm of the heavens on earth. The interplay of the central dome with the surrounding apsidal spaces and peripheral chapels not only enhances the building’s functionality but also imbues it with profound symbolic meaning (Krautheimer 47; Kitzinger 65).

The exterior of San Vitale is characterized by its robust brick construction and the use of decorative bands that echo classical Roman architectural traditions while also anticipating later Byzantine motifs. Inside, the basilica’s interior is arranged around a central nave that radiates outward, creating a unified space that is both contemplative and grandiose. The spatial organization, which incorporates a series of arches, vaults, and intricate brickwork, demonstrates the technical ingenuity of Byzantine architects and reflects a deliberate effort to harmonize form and function (Cormack 92; Mango 117).

In addition to its plan and construction techniques, the building’s proportions and orientation were carefully chosen to create a setting conducive to the display of its elaborate mosaic program. The architectural innovations of San Vitale laid the groundwork for subsequent religious structures throughout the Byzantine world and beyond.

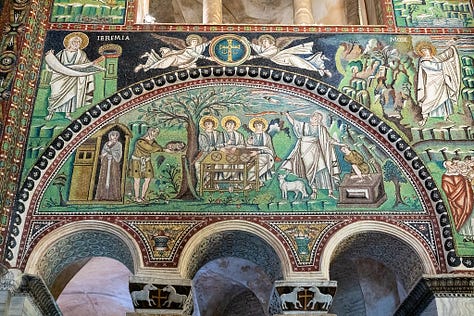

The artistic heart of San Vitale lies in its extensive and remarkably preserved mosaics, which cover walls, ceilings, and arches. These mosaics are not merely decorative; they constitute a comprehensive visual program that intertwines imperial ideology with Christian symbolism. One of the most celebrated mosaics is that of Emperor Justinian and his retinue, which occupies a central position in the apse. This mosaic portrays Justinian in a quasi-divine light, underscoring his role as both a temporal ruler and a divinely appointed leader. The figures are rendered with lifelike detail and are set against a luminous background of gold tesserae, which evoke the radiance of heaven (Mango 117; Cormack 97).

Other mosaic panels and frescoes depict scenes from the life of Christ, allegorical figures, and representations of saints, each carefully designed to convey theological messages about salvation, divine order, and the eternal struggle between good and evil. The use of gold, vibrant hues, and meticulously cut tesserae creates a multisensory experience intended to inspire awe and spiritual contemplation. These artistic techniques reflect the high technical standards and innovative spirit of Byzantine mosaicists and serve as visual embodiments of the era’s liturgical and doctrinal priorities (Kitzinger 72; “Mosaics of San Vitale”).

The iconographic program of San Vitale is a synthesis of classical motifs and Christian themes. The strategic placement of imperial and sacred imagery within the spatial framework of the basilica underscores the intimate connection between church and state, a recurring theme in Byzantine art. Through these mosaics, the basilica communicates a powerful narrative that affirms both the legitimacy of Justinian’s reign and the transformative power of the Christian faith.

Constructed during a time of both political ambition and religious fervor, the Basilica of San Vitale functioned as an ideological statement as much as it did a house of worship. The basilica’s lavish decoration and intricate iconography served as visual rhetoric to reinforce the divine right of the Byzantine emperor and to promote the synthesis of secular and sacred authority. The mosaic portrait of Emperor Justinian, for example, is emblematic of how art was used to legitimize imperial power by aligning the ruler with divine providence (Mango 123; Norwich 90).

The dedication of the basilica to Saint Vitalis further underscores its dual function. By venerating a local martyr and saint, the building connected the imperial project with the broader Christian narrative of sacrifice, redemption, and eternal life. In this context, the basilica became a locus for both devotional practice and imperial propaganda, where religious imagery was mobilized to express political ideals and to foster a sense of communal identity among its viewers (Cormack 100).

San Vitale’s integrated program of art and architecture was designed to engage its audience on multiple levels. Its spatial arrangement, ornamental features, and mosaic iconography worked in concert to create an immersive environment that communicated a coherent message: the Byzantine state was divinely sanctioned, and its rulers were the earthly representatives of heavenly order. This synthesis of art, religion, and politics remains a defining characteristic of Byzantine cultural production and continues to inform contemporary interpretations of the basilica (Krautheimer 53; Kitzinger 80).

Today, the Basilica of San Vitale is recognized not only as an architectural and artistic marvel but also as a crucial link to the heritage of Byzantine civilization. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, San Vitale attracts scholars, conservationists, and tourists from around the globe. The basilica’s ongoing conservation has been the subject of extensive interdisciplinary research, aimed at preserving its delicate mosaics and ancient structure while addressing the challenges posed by environmental and human-induced factors (UNESCO; “San Vitale”).

Modern conservation efforts have integrated advanced imaging technologies, chemical analysis, and meticulous restoration techniques to ensure the basilica’s survival for future generations. Projects undertaken by international teams have shed new light on the original construction methods and decorative schemes employed by Byzantine artisans. These studies not only contribute to the physical preservation of San Vitale but also deepen our understanding of early Byzantine artistic practices and technological innovations (“Mosaics of San Vitale”; Krautheimer 60).

Moreover, San Vitale continues to influence contemporary art and architecture. Its innovative spatial design and rich iconography have inspired countless scholars and practitioners in fields ranging from art history to architectural conservation. The basilica serves as a touchstone for debates about the relationship between art and power, the evolution of religious symbolism, and the methods by which ancient heritage can be integrated into modern cultural identity (Cormack 105; Mango 130).

The legacy of San Vitale is thus multifaceted: it is a monument to the artistic and architectural achievements of the 6th century, a visual document of the ideological currents of Byzantine rule, and a living laboratory for modern conservation science.

The Basilica of San Vitale stands as an enduring symbol of Byzantine ingenuity and spiritual ambition. Through its groundbreaking architectural design, its breathtaking mosaic program, and its layered religious and political symbolism, San Vitale encapsulates the complex interplay of art, faith, and power in 6th-century Ravenna. The continued scholarly investigation and rigorous conservation of this monument attest to its universal significance and its lasting impact on the study of early Byzantine culture. As both a work of art and a historical document, San Vitale remains a vital source of insight into the aspirations and achievements of an empire that sought to unite the divine with the earthly.

References:

Cormack, Robin. Byzantine Art. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Krautheimer, Richard. Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. Penguin Books, 1986.

Kitzinger, Ernst. Byzantine Art in the Making: Main Lines of Stylistic Development in Mediterranean Art, 3rd–7th Century. Faber and Faber, 1977.

Mango, Cyril. The Art of the Byzantine Empire. University of Chicago Press, 1972.

Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium: The Early Centuries. Penguin Books, 1988.

Basilica of San Vitale. Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.,

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Basilica-of-San-Vitale. Accessed 7 Jan. 2025.

Mosaics of San Vitale. The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/sanv/hd_sanv.htm. Accessed 7 Jan. 2025.

San Vitale. Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online,

https://www.oxfordartonline.com. Accessed 15 Feb. 2025.

San Vitale. UNESCO World Heritage Centre,

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/788. Accessed 7 Jan. 2025.