Women’s art has long served as both a mirror and a catalyst for social change. In moments of political turbulence, from the suffrage struggles of the late nineteenth century to the post, World War II reordering, from the civil rights and anti-war protests of the 1960s–70s to contemporary global crises, women artists have used their creative practices to document trauma, challenge injustice, and propose alternative futures. Their work teaches us that art is not merely decorative but a potent vehicle for representation, resistance, and the reimagining of history.

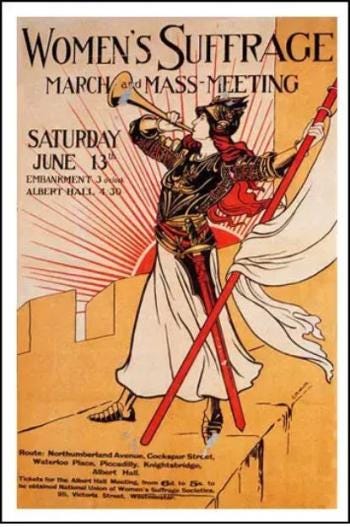

In the context of the suffrage movement and early feminist art, women fought not only for political rights but also for the right to represent themselves on their own terms. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as women mobilized for the right to vote, visual campaigns became an essential tool for spreading their message. Organizations such as the Artists’ Suffrage League in the United Kingdom produced posters, pamphlets, and postcards that employed bold typography and arresting imagery to disrupt the dominant narratives of domesticity and passivity. These artworks, which transformed the familiar into a platform for political engagement, reconfigured the private space of the home into one of public protest. Such innovative strategies helped galvanize public support and brought the voices of disenfranchised women into mainstream consciousness, as discussed in the National Endowment for the Arts report “Creativity and Persistence” (NEA 2018). In a similar vein, American suffragist artists repurposed traditionally feminine crafts like embroidery to create protest banners that challenged gender norms and provided visual evidence of women’s determination to claim their rights (McCracken).

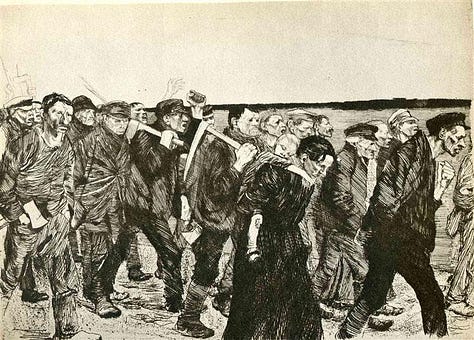

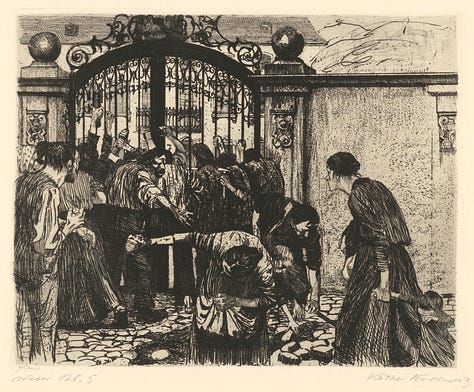

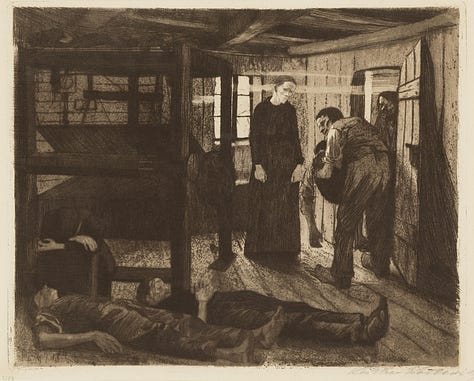

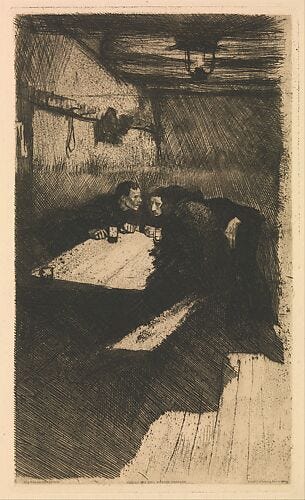

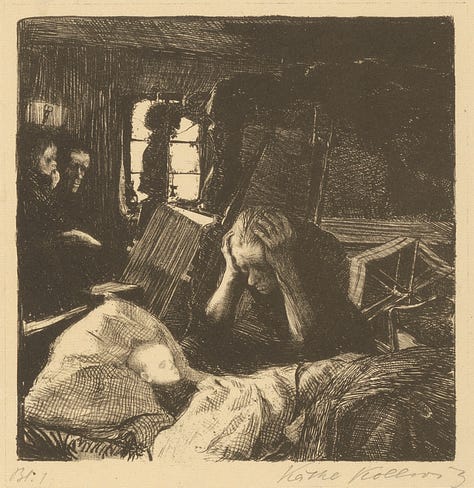

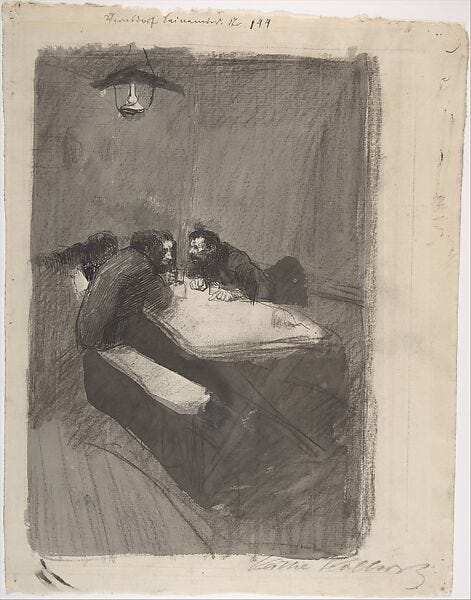

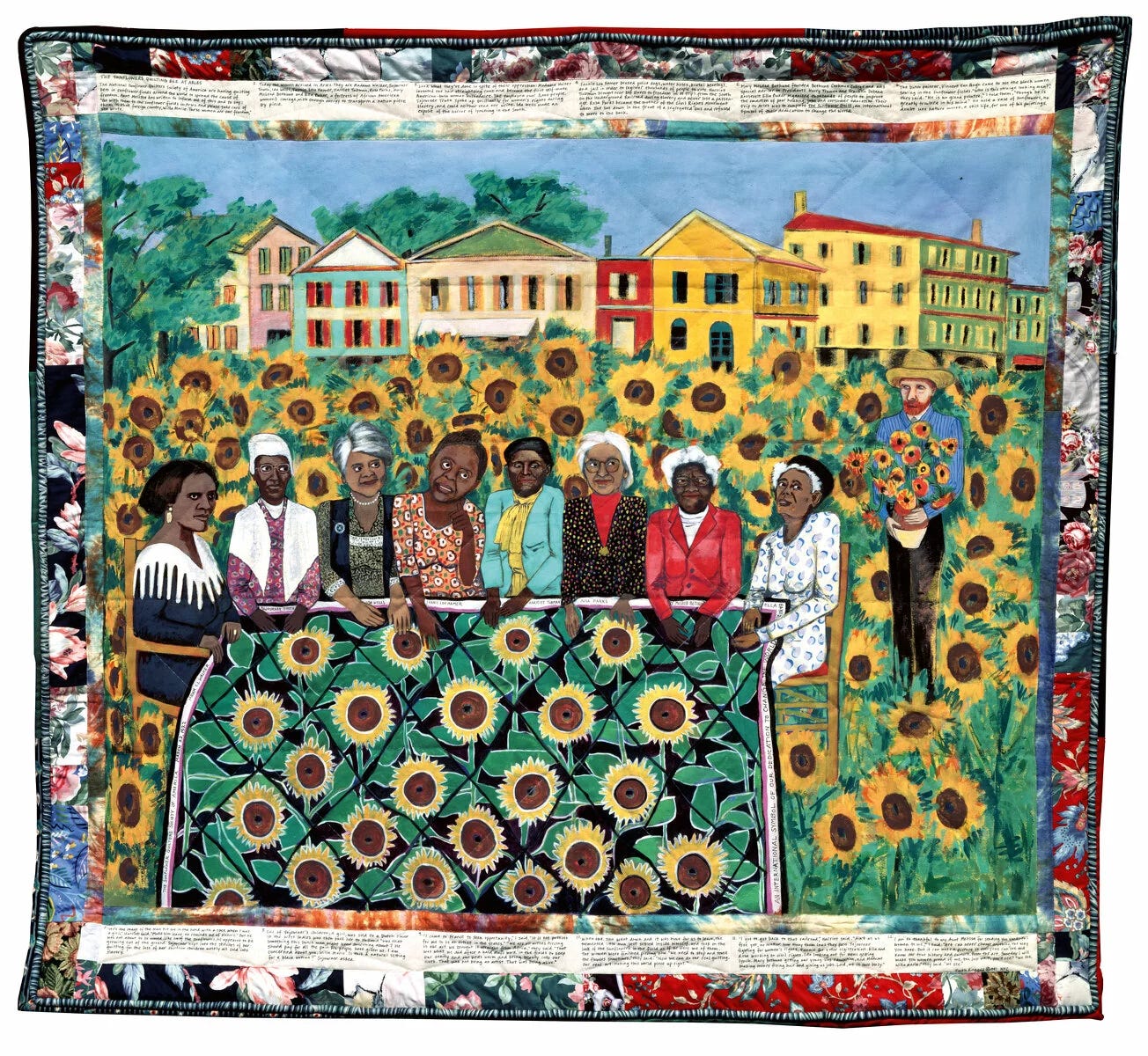

Following the devastations of World War II, the world entered a phase of intense social and political reordering, during which women artists responded by examining the human cost of war and the deep-seated patriarchal structures that had contributed to the conflict. Käthe Kollwitz, for instance, produced powerful etchings and lithographs, most notably in her cycle The Weavers (1898–1900), that came to symbolize the suffering of the working class and the personal losses experienced during wartime. Although Kollwitz’s cycle was originally created at the end of the nineteenth century, its themes resonated strongly in the postwar era, when societies were forced to confront both collective trauma and the inequalities that had precipitated such conflicts (Tate). Similarly, Faith Ringgold’s narrative quilts from the 1960s and 1970s, such as those in her American People Series, interwove personal memory with political critique to document the pain of war and racial injustice, offering both a form of mourning and a clarion call for transformation (Ringgold; Smithsonian American Art Museum). These examples illustrate that post-World War II art by women did more than record history; it actively questioned and reimagined the social order.

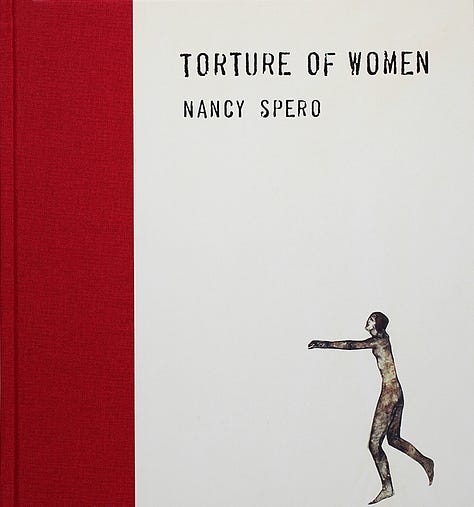

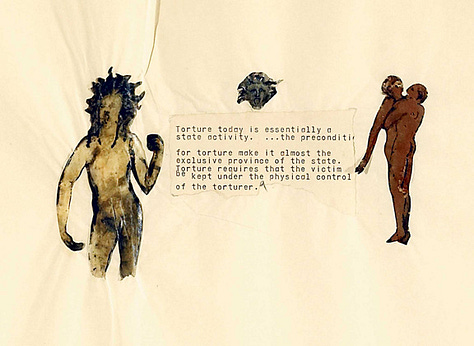

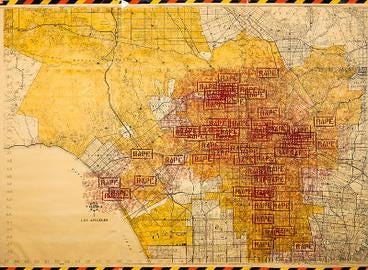

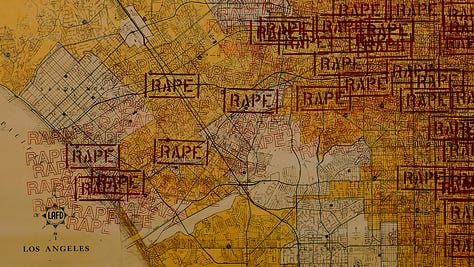

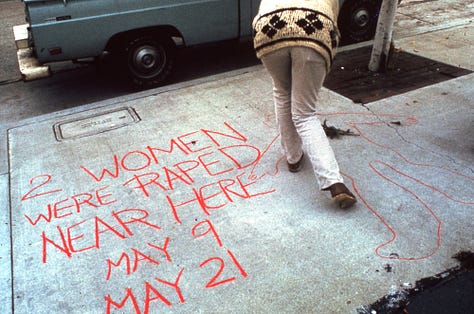

The civil rights movement, anti-war protests, and other intersectional struggles of the 1960s and 1970s further broadened the scope of women’s artistic responses. In this era, women like Nancy Spero and Suzanne Lacy created works that directly engaged with issues of racial injustice, sexual violence, and militarism. Spero’s scroll paintings, including works such as Torture of Women (1976) and Notes in Time on Women (1979–1981), combined collage, printmaking, and performance to evoke the brutal realities faced by marginalized women while mobilizing communities to demand change (Spero; Whitney Museum of American Art). Suzanne Lacy’s performance piece Three Weeks in May (1977) not only confronted the pervasive issue of sexual violence but also used live action and public space to encourage empowerment and collective resistance. Moreover, the mural movement spearheaded by Chicana artists, exemplified by Judy Baca’s The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1984–1987), reclaimed public spaces to rewrite narratives of racial and gender marginalization (Baca; The Guardian, 2025). Together, these varied practices demonstrate that art during periods of upheaval is multifaceted; it serves to document historical trauma, critique oppressive systems, and envision new, more inclusive futures.

In more recent times, the global crises of the twenty-first century have spurred contemporary women artists to once again harness art as a tool for resistance and remembrance. The Belarusian artist Xisha Angelova, for example, has created a monumental series of portraits, over 1,000 images of political prisoners, to bear witness to the repressive policies of authoritarian regimes and to break the cycle of silence that has defined her country’s history (Angelova, 2025). At the same time, Chicana and Filipino artists have continued to build on the legacy of their predecessors by using murals, assemblages, and mixed-media installations to address the enduring legacies of colonialism, labor exploitation, and cultural erasure. These artworks reveal the interconnectedness of historical struggles with contemporary issues, emphasizing that the fight for justice is both ongoing and globally interconnected (González, 2019; Datuin, 2017).

From these historical and contemporary contexts, several key lessons emerge. First, the power of representation is paramount; by centering their own voices and experiences, women artists challenge dominant narratives and create spaces where marginalized stories can be heard. As Whitney Chadwick argues in Women, Art, and Society, the act of self-representation is a radical political gesture that redefines history from a more inclusive perspective (Chadwick, 1991). Second, art can serve as a potent medium of resistance and memory. Whether it is through the visceral imagery of Kollwitz’s etchings or the evocative narrative quilts of Ringgold, these artworks transform personal grief and collective trauma into a call for social transformation. The work of Nancy Spero, which intertwines the personal with the political, demonstrates that the act of remembering is itself an act of defiance against oppressive structures. Third, the integration of art and activism underscores that creative practice is inherently political. The collaborative projects of the Guerrilla Girls, as well as community-based initiatives like those of Chicana muralists, reveal that art can galvanize communities, mobilize dissent, and foster collective empowerment. Finally, these artistic practices encourage the building of inclusive and pluralistic narratives. By employing intersectional approaches that consider race, class, gender, and sexuality simultaneously, women’s art challenges monolithic historical accounts and enriches our understanding of social reality (Dekel; Pollock).

Scholars have applied diverse theoretical frameworks to analyze the contributions of women artists during times of upheaval. Feminist art history, as articulated by Lucy Lippard in From the Center, foregrounds the political dimensions of art created by women and critiques the institutional biases that have historically marginalized their work (Lippard, 1976). Postcolonial theory and intersectionality, explored in works such as Tal Dekel’s Gendered – Art and Feminist Theory and Griselda Pollock’s writings, offer critical lenses for examining how art not only reflects personal experiences but also interrogates broader social and cultural dynamics (Dekel, 2013; Pollock, 1996). Interdisciplinary methodologies, which combine archival research, oral histories, and visual analysis, have proven essential for documenting and contextualizing women’s contributions. Digital archives maintained by institutions such as the Smithsonian and MoMA provide primary sources that trace the evolution of feminist art movements and enable researchers to map the connections between historical protests and contemporary creative practices. For example, archival materials from the Artists’ Suffrage League reveal how visual rhetoric was mobilized to challenge political exclusion, while studies of contemporary Chicana art underscore the ongoing dialogue between indigenous memory and modern activism (NEA, 2018).

The art produced by women during times of social upheaval offers enduring lessons for contemporary society. These works serve as both a record of historical struggle and a call to action, demonstrating that art is not a passive reflection of reality but an active force capable of transforming it. By centering marginalized voices and challenging dominant narratives, women’s art reaffirms the importance of representation and the power of memory. The fusion of art and activism, as seen in the suffrage movement, the post–World War II era, the civil rights and anti-war movements, and contemporary global protests, illustrates that creative practice is an integral part of political resistance. As we navigate a rapidly changing world, these artistic legacies inspire us to embrace inclusivity, mobilize collective action, and continuously reimagine what it means to create a just and equitable society.

The lessons gleaned from this body of work are clear: representation matters, art is a powerful tool for resistance and remembrance, and the intersections of diverse identities enrich our collective historical narrative. In an era of digital proliferation and social fragmentation, the enduring legacy of these women reminds us that creativity can be both a refuge and a revolutionary force. Their work challenges us to question the status quo, to reframe our histories, and to forge paths toward a more inclusive future.

References:

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. Thames & Hudson, 1991.

Dekel, Tal. Gendered – Art and Feminist Theory. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013.

Art the Fueled the Fight for Women’s Suffrage. National Endowment for the Arts, 2018, https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Creativity-and-Persistence-0820.pdf.

Kollwitz, Käthe. The Weavers. 1898–1900. Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/kollwitz-the-weavers-t03788.

Lippard, Lucy R. From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women's Art. E.P. Dutton, 1976.

Pollock, Griselda. Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts: Feminist Readings. Routledge, 1996.

Ringgold, Faith. American People Series. 1963. MoMA, www.moma.org/s/explore/collection/artist/3255.

Spero, Nancy. Notes in Time on Women. 1979–1981. Whitney Museum of American Art, 2009.

Chicano and Chicana Art. Duke University Press, https://www.dukeupress.edu/chicano-and-chicana-art. Accessed 20 Jan. 2025.

Women, Art, and the Suffrage Movement. Journal of Women’s History, vol. 11, no. 3, 1999, pp. 45–67. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30031712.

Feminist Art and Activism in the 1970s. Art Journal, vol. 52, no. 1, 1993, pp. 34–48. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/776172.

Civil Rights, War, and Women’s Art. American Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 3, 2000, pp. 539–562. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40103007.

Beautifully written. So many truths here. This reminds me that to create as a woman is to carry forward a legacy of resistance and remembrance. Art, for me, is memory, protest, offering, and hope. I don’t make it to decorate the world—I make it to understand it, to change it, and to leave something honest behind.

It feels like a responsibility—to those who came before, and those who will come after.

It is so great to see Kollwitz included. I don’t think her legacy has been as well taught as it should be. Like Simone Weil, we just seem to culturally skate by them because they are not glamorous or trendy. Yet the catharsis of their work is unmatched.

It takes a person outside themselves to do what these women have done. You honor them well.