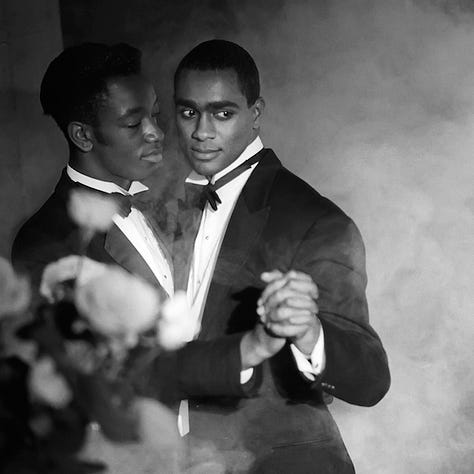

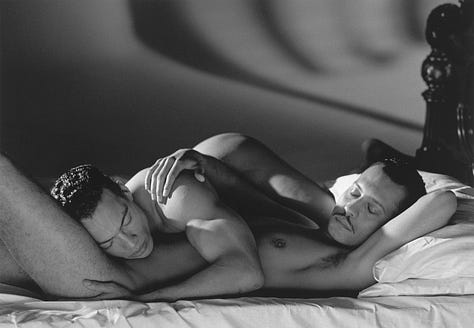

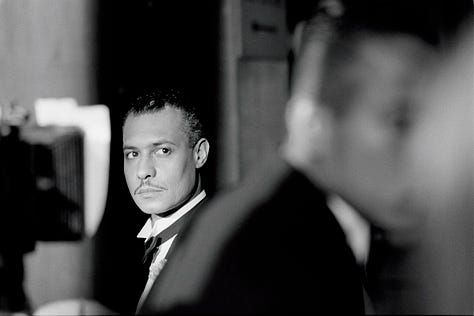

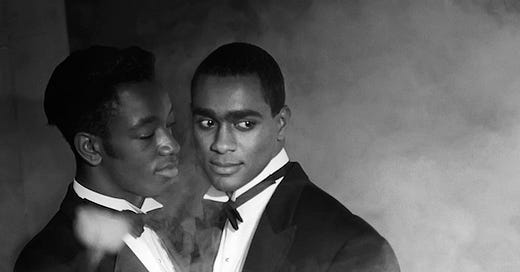

In his four-decade career, Sir Isaac Julien has pioneered a transnational queer aesthetic that fuses poetic cinema, multi-screen installation, and critical historiography to interrogate the intertwined legacies of race, sexuality, and colonialism. As an openly gay Black artist working between London and California, Julien’s projects from the cult classic Looking for Langston (1989) to immersive nine-screen installations like Ten Thousand Waves (2010), forge new modes of representation for LGBTQ diasporic subjects, asserting both visibility and imaginative autonomy.

Born on 21 February 1960 in London to Saint Lucian parents, Julien was one of five children navigating post-war Britain’s fraught racial landscape (moma.org). At Saint Martin’s School of Art (1982–1985), he studied painting and fine-art film and co-founded the Sankofa Film and Video Collective in 1983 with Martina Attille, Maureen Blackwood, Nadine Marsh-Edwards, and Robert Crusz, an artist-run group devoted to “developing an independent black film culture” (Sankofa Film and Video Collective) (en.wikipedia.org). Sankofa’s early work, including Julien’s directorial debut Who Killed Colin Roach? (1983) and Territories (1984), laid the groundwork for his interdisciplinary practice by blending documentary urgency with avant-garde formalism.

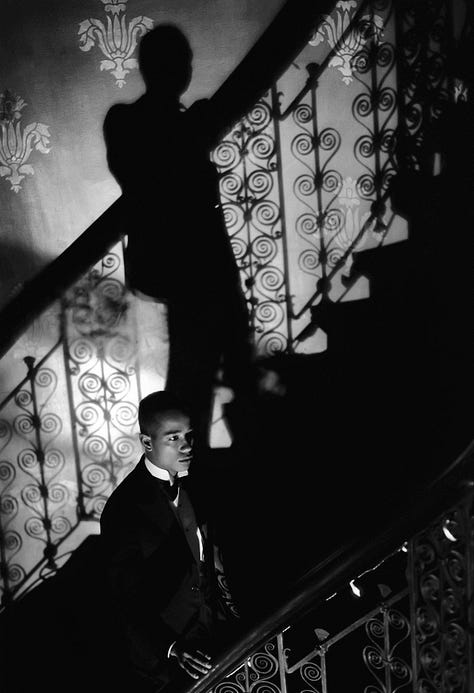

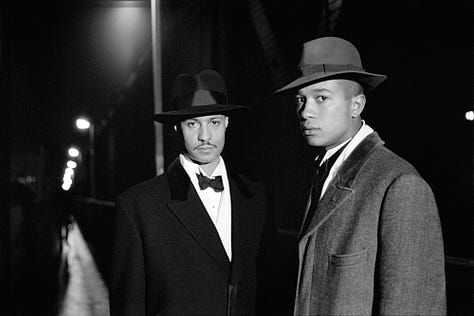

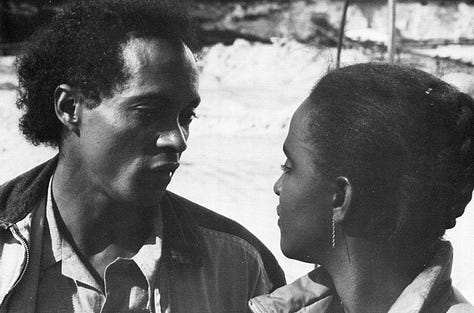

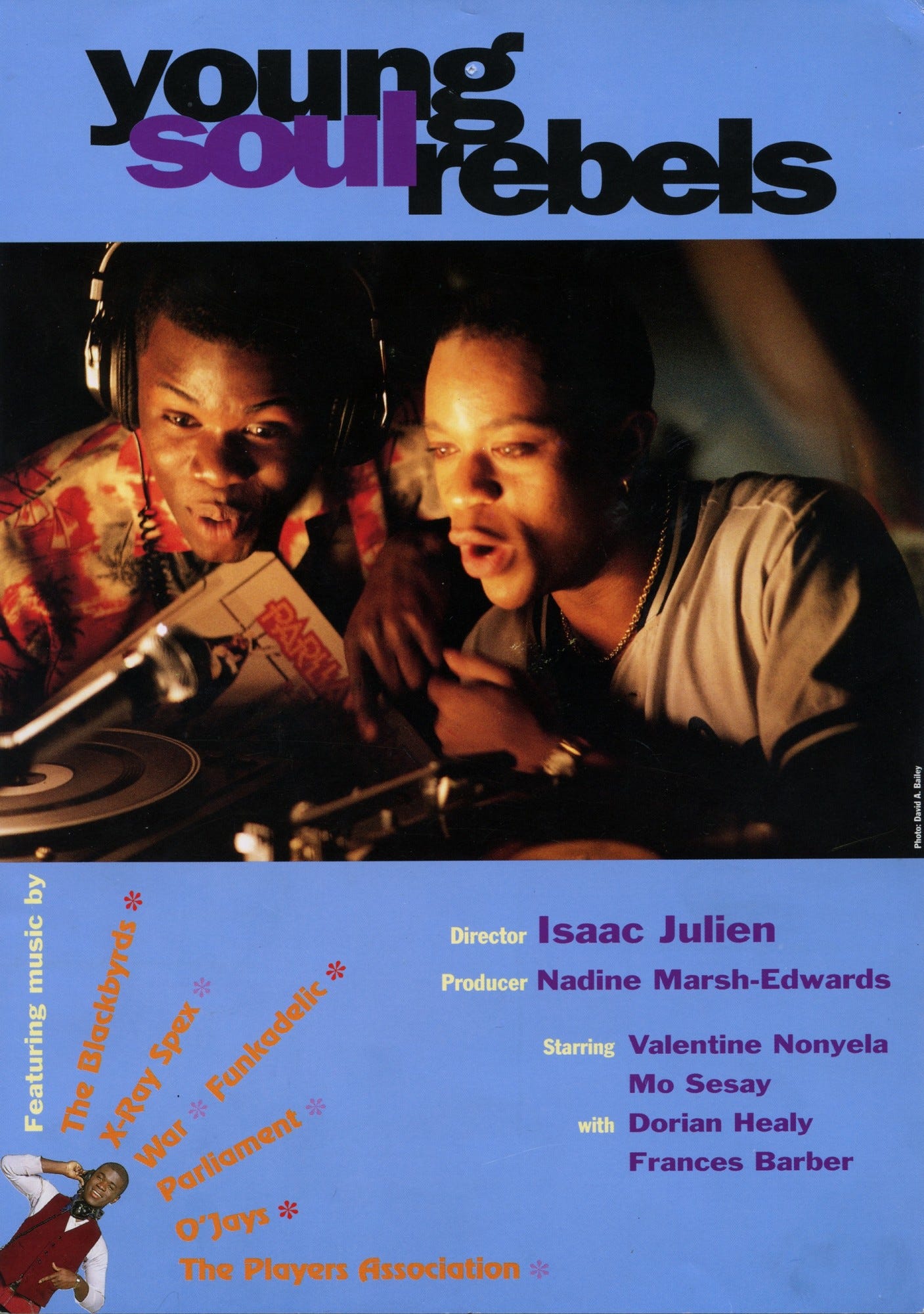

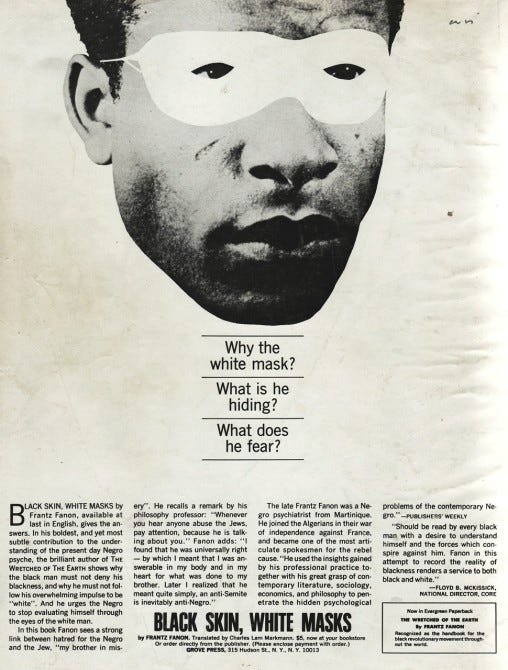

Julien’s first major solo film, Looking for Langston (1989), intercuts archival images of Harlem Renaissance icons with staged performances and Stuart Hall’s poetic voice-over to recover erased queer lives (en.wikipedia.org). It won the Teddy Award at the 1989 Berlin International Film Festival. In Passion of Remembrance (1986), co-directed with Maureen Blackwood, Julien critiques homophobia within leftist movements by foregrounding Black feminist and queer perspectives (The Passion of Remembrance) (bfi.org.uk). Young Soul Rebels (1991) maps a murder mystery onto London’s burgeoning rave scene, earning the Critics’ Week Prize at Cannes (moma.org), while Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask (1996) adapts Fanon’s decolonial theory into a lyrical cinematic essay (en.wikipedia.org).

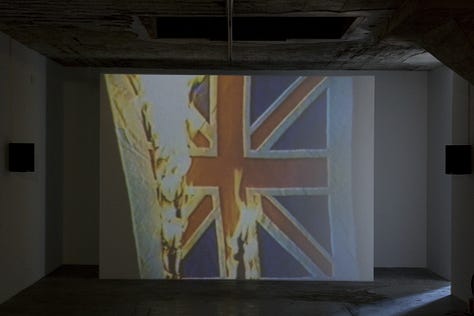

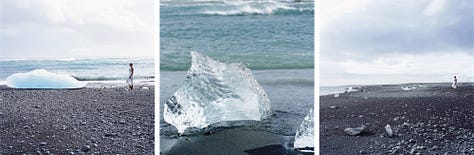

By the early 2000s, Julien had shifted toward immersive installations that layer archival footage, staged performance, and landscape. True North (2004) presents a three-screen journey across an Arctic expanse, tracing explorer Matthew Henson’s fraught quest to the Pole (nararoesler.art). Baltimore (2003) re-imagines Baldwin’s unrealized novel across four screens, juxtaposing urban streets with intimate close-ups to explore interracial desire (moma.org). Ten Thousand Waves (2010), a nine-screen installation first shown at the Biennale of Sydney, weaves narratives of Chinese cockle pickers who died in Morecambe Bay with Mazu-mythology and diasporic memory (isaacjulien.com). In Playtime (2013), Julien turns his lens on the art market itself, following six archetypes, from the Hedge Fund Manager to the House Worker, across multiple channels to critique global capitalism (isaacjulien.com). His recent Once Again… (Statues Never Die) (2022) meditates on Alain Locke’s lost museum project, displacing African sculpture and contemporary Black bodies into a four-channel dialogue.

Julien’s work is deeply collaborative, bringing together cultural theorists and fellow artists. Stuart Hall’s narration in Looking for Langston and Frantz Fanon underscores Julien’s commitment to theory as image (Isaac Julien) (en.wikipedia.org). His Sankofa colleagues, Martina Attille (Dreaming Rivers, 1988) and Maureen Blackwood, helped shape Passion of Remembrance into a critique of sexism and homophobia within radical politics (bfi.org.uk). Julien also engaged choreographer Russell Maliphant for Cast No Shadow (2007), his first evening-length stage work, blending dance and film in performative dialogue.

A major retrospective, What Freedom Is to Me, spanned Tate Britain in 2021, surveying Julien’s film-installation practice from the 1980s onward (isaacjulien.com). The de Young Museum’s 2025 exhibition Isaac Julien: I Dream a World will chart his transatlantic vision with ten installations, including Looking for Langston and Lessons of the Hour: Frederick Douglass (2019) . Julien’s publications, Red Africa (2016) and Playtime and Kapital (2016), extend his cinematic concerns into critical writing (isaacjulien.com). His accolades include a Turner Prize nomination (2001), the Grand Prix at the 2003 Kunstfilm Biennale, election as a Fellow of the British Academy (2024), and a knighthood for services to diversity and inclusion in art (2022) (en.wikipedia.org).

Sir Isaac Julien’s oeuvre inhabits the interstices of queer theory, postcolonial critique, and cinematic innovation. By centering LGBTQ Black experiences within experimental narratives and immersive installations, he disrupts hegemonic archives and asserts the transformative power of art to reimagine collective futures. Julien’s work continues to inspire new generations of artists and scholars, reminding us that the lens of poetic cinema remains a vital instrument of queer diasporic visibility.

References:

Isaac Julien. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Julien. (moma.org)

Ten Thousand Waves. MoMA, Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1382. (moma.org)

Playtime. Isaac Julien, www.isaacjulien.com/projects/playtime/. (isaacjulien.com)

True North Series. Triptych of digital prints, Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, 2004. (icamiami.org)

Ten Thousand Waves. Multi-screen installation, 2010. (isaacjulien.com)

Sankofa Film and Video Collective. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sankofa_Film_and_Video_Collective. (en.wikipedia.org)

Jackson, Sherry Thomas. Strike a Pose, Forever: The Legacy of Vogue and its Recontextualization. European Journal of American Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 2017, pp. 26–42. (isaacjulien.com)

Passion of Remembrance: the Sankofa Collective’s Remarkable Tapestry of Black British Experience. BFI, 28 Apr. 2023, www.bfi.org.uk/features/passion-remembrance-sankofa-collectives-remarkable-tapestry-black-british-experience. (bfi.org.uk)

Videofreex. Gay for a Day. 16 mm film, 1976. (lacma.org)

Hammer, Barbara. Dyketactics. Film, 1975. (youtube.com)

Hughes, Holly. My Life as a Glamour Don’t. Performance, Women’s One World Café, New York, c. 1980.

Segal, George. Gay Liberation. White-bronze sculpture, Christopher Park, New York, 1979–1980. (en.wikipedia.org)

von Praunheim, Rosa. It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives. Bavaria Film, 1971. (icamiami.org)

Weinberg, Jonathan, editor. Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989. Rizzoli, 2019. (isaacjulien.com)

Isaac Julien: I Dream a World. San Francisco Chronicle, 12 Jan. 2025, www.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/article/isaac-julien-de-young-retrospective-20061133.php.

Julien, Isaac. Lessons of the Hour: Frederick Douglass. Multi-screen installation, 2019.

Women’s Interart Center. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women’s_Interart_Center. (mplus.org.hk)

It is interesting to imagine Julian’s excitement as the medium for translating his ideas and imagery into experience through technology has expanded the capacity of his oevre rather than narrowed it. So many verticals in art struggle to adapt and reinvent themselves when in fact his vision has been ahead the whole time.

Storytelling through multiple voices toward one goal while also threading the needle of controversy, identity and colonialism is a tall order. His work has been prescient, surpassing its expectation in how well it translates over time. Indeed one could say Isaac has managed to create the very relevance others aspire to catch up to.