Oswaldo Guayasamín (1919-1999) stands as one of the most important and influential figures in Latin American art. Born in Quito, Ecuador, to a poor Indigenous family, Guayasamín's work is a profound reflection on human suffering, the pain of injustice, and the struggles of marginalized peoples. His work blends the traditions of social realism with modernism, focusing heavily on the plight of Indigenous communities in Latin America, as well as broader global issues of war, poverty, and oppression.

Oswaldo Guayasamín was born into an Indigenous family of humble origins, a background that profoundly shaped his worldview and artistic approach. His mother was of Quechua descent, and his father worked as a carpenter and taxi driver. Growing up in poverty, Guayasamín witnessed firsthand the inequalities that marked Ecuadorian society, where Indigenous people were often relegated to the margins. His upbringing in such an environment gave him an acute awareness of social injustice, which would later become a central theme in his artwork.

Guayasamín showed early artistic promise and enrolled in the School of Fine Arts in Quito, where he trained under prominent local artists such as Victor Mideros. His early work was marked by a clear influence of the Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, who were known for their socially and politically charged murals. These artists introduced Guayasamín to the power of art as a tool for activism, a lesson he carried with him throughout his career.

Guayasamín's art can be categorized within the broader framework of Social Realism, a movement that emerged in the early 20th century as a response to the growing inequalities of the industrial world. Social Realist artists sought to depict the harsh realities of working-class life, often focusing on themes of poverty, labor, and oppression. Guayasamín, however, expanded this focus, placing the suffering of Indigenous peoples and the atrocities of war at the forefront of his artistic vision.

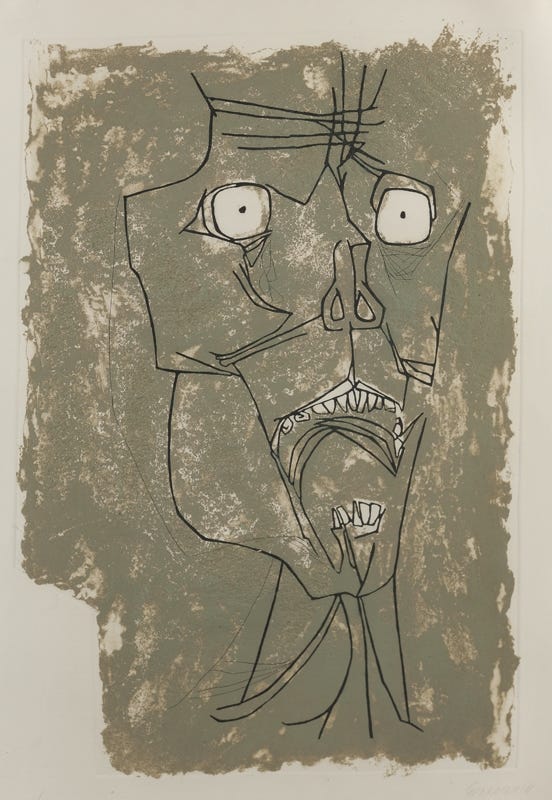

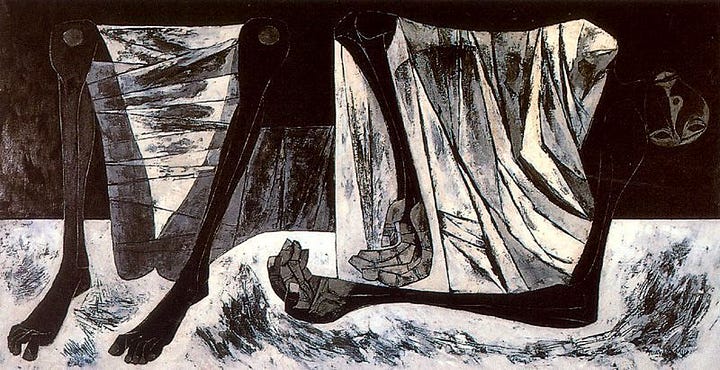

His work is marked by a profound expression of pain, suffering, and anger. In paintings such as La Edad de la Ira (The Age of Wrath), Guayasamín explores the violence of the 20th century, including the Spanish Civil War, the Holocaust, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. His use of stark colors, exaggerated forms, and distorted human figures evokes a sense of anguish and despair. The gaunt faces, elongated hands, and hollow eyes that characterize his figures symbolize the collective pain of humanity, and his palette of dark, somber tones reinforces the gravity of his subjects.

The monumental series La Edad de la Ira is perhaps the most comprehensive representation of Guayasamín’s worldview. Spanning several decades of his career, this collection addresses global atrocities, particularly focusing on the suffering caused by war, dictatorship, and poverty. The series portrays dehumanized figures, often stretched and contorted in postures of extreme pain and grief, reflecting the artist’s condemnation of violence and inhumanity. The series is a visual documentation of the collective trauma experienced in the 20th century, with a particular focus on Latin America’s history of political repression.

While Guayasamín is often celebrated as a Hispanic artist, his work is deeply rooted in his Indigenous heritage. The tension between his Indigenous identity and his position within the broader Hispanic world is a significant aspect of his work. Guayasamín's Indigeneity is most visible in his focus on the plight of Indigenous peoples in Ecuador and Latin America. Works like El Grito (The Scream) and Los Condenados (The Condemned) depict the suffering of Indigenous populations, particularly in the face of colonialism and postcolonial oppression.

Guayasamín’s portrayal of Indigenous figures often emphasizes their humanity, contrasting the stoic dignity of the oppressed with the brutality of their oppressors. His figures are frequently deformed, with exaggerated hands and faces, reflecting both their physical suffering and their emotional pain. Through these images, Guayasamín reclaims the representation of Indigenous peoples, challenging the stereotypes and marginalization that had long been imposed upon them by colonial and postcolonial societies.

At the same time, Guayasamín’s work cannot be separated from his broader identity as a Latin American artist within the Hispanic world. His engagement with European modernist styles, such as Cubism and Expressionism, reflects his position within a transnational art movement. His work thus occupies a space that is both deeply local—rooted in the specific struggles of Indigenous and mestizo peoples in Ecuador—and global, addressing universal themes of human suffering and resilience.

Guayasamín’s work is inseparable from his political beliefs. He was a vocal supporter of leftist causes throughout his life and used his art to advocate for social justice. His friendships with political leaders such as Fidel Castro and Salvador Allende further reinforced his role as a politically engaged artist. Guayasamín was not just an observer of political events; he was an active participant in the struggle for a more just and equitable world.

His painting Manos de la Protesta (Hands of Protest) is an iconic image of resistance. Depicting clenched fists raised in protest, the work became a symbol of solidarity with oppressed peoples around the world. Guayasamín's commitment to social justice extended beyond his art. He also founded the Guayasamín Foundation, which seeks to preserve and promote Latin American art and culture, as well as the Capilla del Hombre (Chapel of Man), a museum and cultural center dedicated to the struggles of humanity.

One of Guayasamín’s most significant contributions to both the art world and social activism is the Capilla del Hombre. Completed posthumously, the chapel is an homage to the suffering and resilience of Latin American people. More than just a museum, it is a cultural and artistic center designed to foster reflection on the injustices of history. The architecture, artwork, and concept of the space all reflect Guayasamín’s lifelong mission to bring attention to human suffering and the necessity of compassion and action in the face of oppression.

The chapel houses many of Guayasamín’s most important works, including La Edad de la Ira. Visitors are invited to contemplate the painful history of colonialism, exploitation, and violence that has defined much of Latin America’s history. The chapel stands as a testament to Guayasamín’s belief in the power of art to enact social change, and his dedication to ensuring that the struggles of marginalized peoples are never forgotten.

Oswaldo Guayasamín's legacy as a Hispanic and Indigenous artist is one of profound importance, not only to Ecuador but to Latin American art as a whole. His unflinching depictions of suffering, injustice, and human dignity have cemented his place as one of the most powerful voices in 20th-century art. His work serves as both a historical document and a timeless call to action, reminding viewers of the need to confront the social and political realities of their time.

Guayasamín’s art, infused with both his Hispanic and Indigenous identities, reflects the complexities of Latin American culture, where the legacy of colonialism and the modern struggle for social justice are in constant tension. His work continues to resonate with audiences today, offering a powerful commentary on the enduring issues of inequality, oppression, and human rights. Through his art, Guayasamín sought not only to depict suffering but to inspire hope and action, making his work as relevant today as it was during his lifetime.

References

Barnitz, J. (2001). Twentieth-Century Art of Latin America. University of Texas Press.

Navarro, M. (2009). Oswaldo Guayasamín y la Capilla del Hombre. Ediciones Del Museo.

Ramos, M. (1995). "Indigenous Identity in the Art of Oswaldo Guayasamín." Latin American Research Review, 30(2), 121-135.

Sullivan, E. J. (1996). Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century. Phaidon Press.

Westheim, P. (1990). La pintura contemporánea en Latinoamérica. Siglo XXI Editores.