Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) remains a prominent and celebrated figure in English literature, beloved for his wit, sharp epigrams, and richly crafted works. An Irish-born poet, playwright, and novelist, Wilde became one of the most quotable writers of his era, known as much for his flamboyant persona as for his art. His life story, from early success and social prominence to scandal, imprisonment, and exile, has made him an enduring literary and cultural icon. Wilde’s biography and oeuvre are inseparable from his role as a pioneering LGBTQ figure in literary history, while his influence on aestheticism, theatre, and popular culture continues into the 21st century.

Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde was born on 16 October 1854 in Dublin, Ireland, to intellectually distinguished parents. His father, Sir William Wilde, was a leading ear-and-eye surgeon and antiquarian; his mother, Jane Wilde (née Elgee), was an Irish nationalist poet writing under the pen-name Speranza. Oscar was the second of three children; his older brother William became a journalist and his sister Isola died in childhood. Both Wilde’s parents were deeply involved in Irish literary and cultural life, and Wilde grew up in an environment steeped in literature and folklore.

Wilde was baptized Roman Catholic by his mother, despite the family’s Anglican roots, a choice reflecting his family’s identity and values. He was educated at Portora Royal School in Enniskillen (1864–1871), and subsequently earned scholarships to Trinity College, Dublin (1871–1874) and then to Magdalen College, Oxford (1874–1878). At Oxford Wilde distinguished himself as a classical scholar and poet. He won the Newdigate Prize for poetry in 1878 for his long poem “Ravenna”. During his studies he encountered the ideas of John Ruskin and Walter Pater, who preached “the central importance of art in life.” Wilde embraced the Aesthetic philosophy of art for art’s sake, famously taking to adorning his rooms with fine objects and reportedly musing “Oh, would that I could live up to my blue china!”. Influenced by Pater’s counsel to “burn always with [a] hard, gemlike flame,” Wilde adopted an aesthetic pose and cultivated a wit that would become his trademark. In short, his early life set the stage for a career in which style, beauty, and intellectual cleverness were paramount.

After Oxford, Wilde moved to London and quickly became part of the city’s high society and artistic circles. In the early 1880s, the Aesthetic movement was ascendant, and Wilde flaunted his devotion to beauty through dress and public persona. He self-published a volume of Poems in 1881, though it was greeted coolly by critics. His aesthetic garb and languid wit earned him both admirers and satirical mockery (for example, Gilbert and Sullivan caricatured him as the “fleshly poet” Bunthorne in Patience). Wilde’s social connections also grew; he befriended leading actors (including Sarah Bernhardt) and became a popular lecturer. In 1881–1882 Wilde toured the United States and Canada, delivering over 150 lectures on art and wit. At customs in New York he quipped famously that he had “nothing to declare but my genius”, a remark that captured his brazen spirit.

Wilde’s literary output in the 1880s was eclectic. In 1888 he published The Happy Prince and Other Tales, a collection of fairy stories that reveal his gift for romantic allegory and compassion cloaked in beauty. In 1890–1891 he published his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. This decadent, Faustian tale of a young man who remains eternally beautiful while his portrait ages under the influence of his sins drew both acclaim and outrage. Critics at the time denounced Dorian Gray as “immoral” and “poisonous,” accusing Wilde of proposing that “there is no such thing as a new experience at all”. Wilde defended the novel’s amoral worldview and insisted on art’s autonomy, a stance he had already articulated in essays such as “The Decay of Lying” and Intentions.

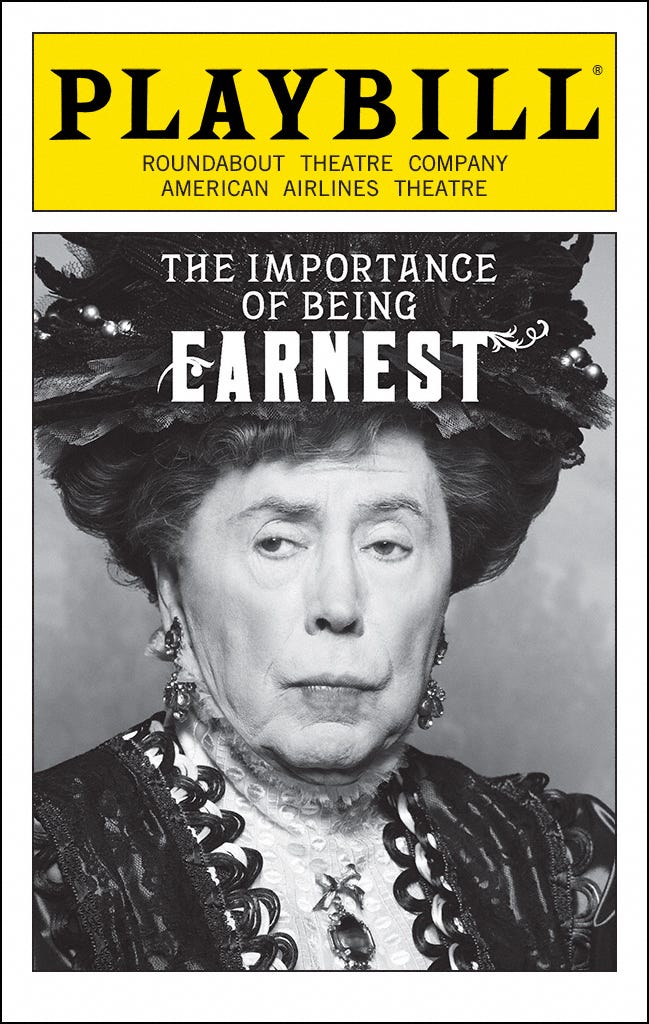

Wilde is best remembered for his plays, which were enormously successful. Starting in 1892 with Lady Windermere’s Fan, Wilde had a string of hit stage comedies. Lady Windermere’s Fan (performed Feb. 1892) delighted audiences with its wit and social satire, and “took England by storm”. This was followed by A Woman of No Importance (1893), An Ideal Husband (1895), and culminating in The Importance of Being Earnest (also 1895), widely regarded as his masterpiece. These comedies, characterized by sparkling epigrams and clever critique of Victorian society, made Wilde “the most popular playwright of his time”. His epigrammatic lines (e.g. “I can resist everything except temptation”) and the playful irreverence of his plots influenced later comic drama, establishing a model for combining sharp social commentary with entertainment. Wilde’s plays also exemplified the Aesthetic embrace of beauty and artifice, even as they gently mocked the hypocrisy of the elite. For example, he famously declared in Earnest, “The truth is rarely pure and never simple,” highlighting both his cynicism and literary flair.

In addition to drama, Wilde wrote poetry and essays. His verse includes The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898), a moving poem about prison life written after his own incarceration. He wrote philosophical and social critiques, such as “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” (1891), which envisages a society that fosters artistic genius, and many prologues and dialogues for the theatre. Throughout his work, Wilde’s style combined paradox and wit with an emphasis on aesthetic values; he often championed art for art’s sake and treated life as a performative canvas. Dorian Gray, Earnest, and his tales remain widely read and produced, securing Wilde’s position in the literary canon.

Wilde’s contributions also lie in the Aesthetic and Decadent movements he exemplified. He championed beauty and individual expression in a period of strict moralism. Unlike earlier reformers, Wilde did not aim to uplift the working class or alleviate social ills; instead, he insisted on the autonomy of art. For instance, in “The Decay of Lying” he famously wrote that art and life imitate each other, yet he reversed conventional Victorian moral expectations. His refusal to moralize distinguished him from many contemporaries. As one scholar notes, Wilde “negotiated all the intellectual, economic and social forces” of late 19th-century society, working sometimes within the Aesthetic Movement but also challenging its norms from the inside. His work gave voice to a new idea that art need not serve didactic ends and that a writer could be celebrated for cleverness itself. These literary contributions, the plays’ social satire, the novel’s exploration of beauty and corruption, the theatrical prologues, and the bold essays, secured Wilde’s influence on the trajectory of modernism and comedy of manners.

Wilde’s personal life was as dramatic as his plays. In 1884 he married Constance Lloyd (née Mary), a Dublin-born sister of an aristocrat, and they had two sons: Cyril (born 1885) and Vyvyan (born 1886). Wilde initially presented himself as a conventional family man, and in the mid-1880s he supported his household partly through journalism and editing. He reviewed for the Pall Mall Gazette and became editor of Woman’s World (which he rebranded The Lady’s World) in 1887–1889. However, Wilde’s private life was more complex; he enjoyed the company of other men even while married, a truth that would later be revealed.

In 1891 Wilde met Lord Alfred Douglas (“Bosie”), a young aristocrat sixteen years his junior. The two formed a close friendship that grew into a romantic and sexual relationship. Wilde also had earlier clandestine liaisons with men such as the Canadian journalist Robert Ross. Homosexual acts were then criminal in Britain under the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885. Wilde’s association with Douglas aroused the anger of Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, who detested Wilde. In 1895 the Marquess publicly accused Wilde of being a “sodomite,” and Wilde (at Douglas’s urging) sued for libel. This decision proved disastrous. Evidence at the libel trial (April 1895) implicated Wilde in homosexual activities; his case collapsed and he was forced to drop the suit.

Britannica and other scholars emphasize that Wilde’s trial became a crucible of Victorian attitudes toward sexuality. Authorities cited Wilde’s novel Dorian Gray and passages of poetry as evidence of his alleged “morality” (or immorality). Ultimately Wilde was arrested and tried for “gross indecency”, a term for homosexual acts, later in 1895. His eloquent defense included his famous explanation of “the love that dare not speak its name”. Asked to clarify this phrase from Douglas’s poem “Two Loves,” Wilde replied: “This love that dare not speak its name,” he said, “is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man ….as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect.”

This powerful speech appealed to classical ideals of friendship and beauty, but it could not overcome the rigid Victorian law. In his retrial Wilde was convicted (May 1895) and sentenced to two years of hard labor. He served his sentence mostly at Reading Gaol, where he experienced the brutality of prison life and wrote De Profundis (a long letter to Douglas) and later The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898) describing the cruelty of incarceration.

Wilde’s persecution transformed him into a symbol of the injustice faced by gay men. Scholars note that the trials revealed “the dual repugnance and fascination of the public with celebrity scandal,” as the Victorian establishment sought to scapegoat those who threatened conventional norms. Wilde’s artistic persona and homosexuality had made him a target; Polini notes that Wilde’s “homosexual literary schema” endangered the Victorian ethos, leading society to persecute him in order to restore normality. Throughout the trials, Wilde’s own words and writings were used against him as evidence of “homo-erotic themes”. His conviction caused an immediate upheaval: creditors forced him into bankruptcy, his plays were shut down in England, and former friends turned away.

Despite the tragedy, Wilde’s legacy as an LGBTQ figure grew over time. In the 20th and 21st centuries he has been widely reclaimed as a gay icon. Scholars and cultural historians recognize that Wilde’s life, including his suffering under anti-homosexual laws, resonates with LGBTQ history. For example, in 2017 Wilde was among 50,000 men in Britain posthumously pardoned under the “Turing Law” (named for Alan Turing) that vacated convictions for homosexual acts no longer illegal. This act implicitly acknowledges that Wilde (and thousands like him) were unjustly persecuted for their sexuality. In recent decades Wilde’s story has been taught and celebrated in LGBTQ contexts worldwide. He is often quoted or referenced at pride events, and his wit about identity and freedom continues to inspire queer readings of his work. Indeed, as Klimchynskaya and others note, Wilde’s own embrace of artifice, he called himself “the first self-made performance celebrity”, can be seen as anticipating modern ideas of identity and representation. Today Wilde stands as one of the great nineteenth-century writers whose life and work intersect meaningfully with LGBTQ cultural history.

Wilde’s influence on literature and society was multi-faceted. In the short term, his dazzling comedies redefined the modern stage. Victorian drama had been dominated by sentimental melodrama or historical spectacle, but Wilde’s comedies of manners (with their crisp dialogue and sophisticated humor) helped pave the way for the “drawing-room comedies” of the 20th century. He mixed social satire with philosophical epigrams, teaching playwrights that sharp wit could illuminate moral hypocrisy. His one novel, Dorian Gray, impacted the genre of the Gothic and the Decadent movement: by infusing a ghostly narrative with swirling ideas of art and sin, he influenced authors from Joris-Karl Huysmans to later decadents. Poets and writers (from W.B. Yeats to T.S. Eliot) would later note Wilde’s paradoxical style and sardonic voice.

On a broader cultural level, Wilde epitomized the Aesthetic Movement’s challenge to Victorian norms. He popularized the idea that life itself could be art, living stylishly and valuing beauty as the highest ideal. His axiom “all art is quite useless” (from Dorian Gray) became a touchstone for debates about art’s social value. Through essays like “The Soul of Man Under Socialism”, Wilde argued that true individualism and creativity require freedom, indirectly influencing later modernist and socialist thinkers. His critiques of marriage, gender roles, and morality, often phrased as paradox, enlivened public discourse and loosened the strict moral codes of the era. For example, his famous maxim “No object is so beautiful that, under certain conditions, it will not look ugly” (from Intentions) invites readers to question accepted ideals. In sum, Wilde’s flamboyance and ideas about art-for-art’s-sake helped erode strict Victorian propriety and inspired a generation to value wit and irony in literature.

In society, Wilde’s downfall itself was a cautionary tale about the consequences of hypocrisy. The 1895 trials caused a backlash, but they also provoked discussion of sexuality that would slowly evolve over the century. Contemporary writers like G.K. Chesterton publicly opposed the trials, and later biographers (such as Hesketh Pearson) painted Wilde as a tragic martyr of intolerance. Wilde’s remarks in prison, he quipped that “if some fellow is silly enough to want me, I won’t say no” about Queen Victoria after a pardon was suggested, have become part of folklore, showing that his wit endured even in hardship.

In modern culture, Wilde’s legacy lives on through continued readings and portrayals of his life and works. His plays are staples on theatre repertoires worldwide. The Importance of Being Earnest in particular remains beloved and frequently staged. His novel and stories are studied in literature courses, and countless editions of Dorian Gray have been published. Wilde’s personality, the flamboyant dress, the golden lilies on handkerchief, has become an archetype for the dandy and intellectual wit.

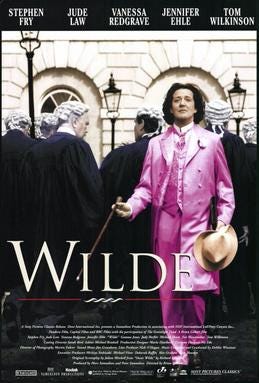

His life has inspired numerous artistic portrayals. In 1997, Brian Gilbert directed the biopic Wilde, starring Stephen Fry as Oscar and Jude Law as Bosie. The film is noted for its faithful script and strong performances: The Guardian praised Fry’s casting as “perfectly” matching Wilde’s manner. In drama, David Hare’s 1998 play The Judas Kiss vividly depicts Wilde’s final days before and after imprisonment. These works underscore how Wilde’s story, genius undone by social mores, continues to fascinate.

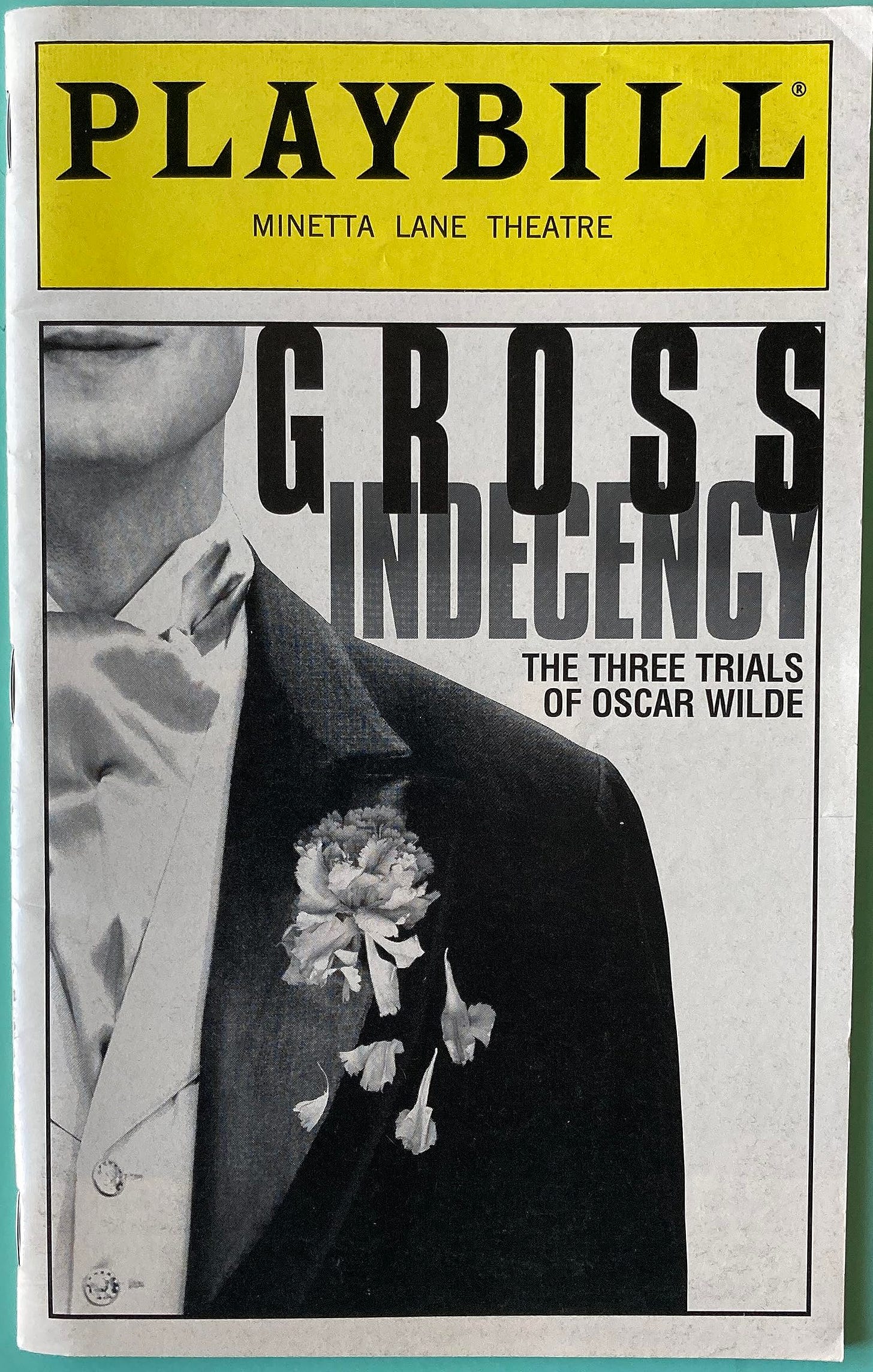

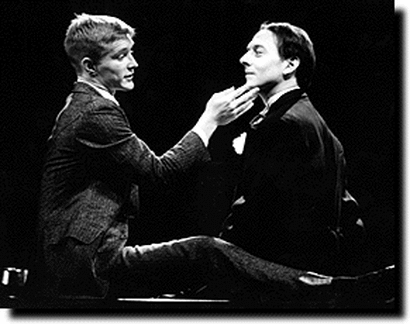

The most enduring theatrical representation is Moisés Kaufman’s 1997 play Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde. This play has been widely produced and acclaimed for its innovative form and emotional power. Kaufman’s script is “part docudrama, part classical tragedy”: it weaves together verbatim court transcripts, newspaper accounts, private letters, and interviews to present Wilde’s three trials and downfall. As a Los Angeles Times critic notes, Kaufman’s Gross Indecency “brings strikingly original theatrical flair to an oft-dramatized story,” combining many textual sources into a kaleidoscopic narrative. The play features a deconstructed structure in which a group of actors portray dozens of roles; its form reflects Wilde’s multifaceted persona and the impossibility of a single “truth” in history. In Kaufman’s own words, Gross Indecency is “‘a group of actors quoting from books [that] often have contradictory narratives’ about Wilde’s three trials and downfall”. This approach mirrors Wilde’s aesthetic of paradox and highlights how he himself curated his image.

A particularly notable production of Gross Indecency was its original 1997 Off-Broadway run, where the role of Wilde was played by actor Michael Emerson. Emerson, who would later become a two-time Emmy Award winner for television, won critical acclaim for his Wilde. As Playbill reported, “Michael Emerson, whose title role in Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde garnered critical acclaim”, became associated with the part. The play was a hit: it was “first performed in New York in 1997 [and] .... played an extended, sold-out run Off-Broadway. It starred Michael Emerson as Wilde,” according to theatre writer Carey Purcell. In these performances, Emerson captured Wilde’s eloquent wit, vanity, and pathos, bringing renewed attention to Wilde’s life. The success of Gross Indecency has made it a definitive modern account of Wilde’s trials; it continues to be staged regularly, including anniversary readings and international revivals. Kaufman has said that even 120 years after Wilde’s trials, government censors (as in Russia) can still be frightened by his story, a testament to Wilde’s lasting cultural power.

Beyond Gross Indecency, Wilde’s image appears in other modern media. He has been portrayed on television (for example, in BBC programs) and referenced in literature. His epigrams are frequently quoted on social media and in popular culture to express irony or beauty. For instance, the biography of Princess Diana by Andrew Morton quotes Wilde to capture eccentric wit. Wilde-themed festivals, museum exhibitions, and academic conferences commemorate his work. His birthday (October 16) is sometimes celebrated by literature enthusiasts worldwide.

In the LGBTQ community, Wilde’s legacy as a pioneer of gay visibility has been particularly embraced. Drag performers sometimes quote his lines; at Pride marches his slogans and cause celebre status feature in speeches. The Oscar Wilde Bookshop (founded 1967 in New York) was one of the first gay bookstores in the U.S., reflecting the association of Wilde’s name with gay identity and literary culture. He even appears on an LGBT-themed playing card (part of a set of historical gay figures). These tributes underline how Wilde has come to symbolize both the beauty of gay identity and the injustice of anti-gay persecution.

Oscar Wilde’s life and work occupy a unique place in literary and cultural history. As an author, he contributed enduring comedies, a singular novel, influential essays, and classic short stories, all marked by brilliant wit and a commitment to aesthetic beauty. As an individual, he challenged social norms simply by being himself: he lived in defiance of Victorian conventions, which ultimately led to his downfall during the infamous 1895 trials. These events, while tragic, have elevated Wilde into a symbol of queer resilience and artistic integrity. In modern times, his influence is felt not only in literature and theater but also in his role as an LGBTQ icon. His legacy persists in countless adaptations, from the film Wilde to stage works like Kaufman’s Gross Indecency, and in the continuing relevance of his ideas about art and identity. As one commentator suggests, Wilde remains compelling because his story forces us to confront “the power of language” and who gets to tell whose stories. A century after his death, Wilde’s flame still burns bright, “hard, gemlike,” illuminating questions of beauty, freedom, and authenticity for each new generation.

References:

Beckson, Karl, and René Ostberg. Oscar Wilde. Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Oscar-Wilde. Accessed 26 Feb. 2025.

Brandes, Philip. Theater Review: Gross Indecency at Eclectic Company Theatre. Los Angeles Times, 10 Sept. 2009, L.A. Times, http://www.latimes.com/archives/blogs/culture-monster-blog/story/2009-09-10/theater-review-gross-indecency-at-eclectic-company-theatre.

Klimchynskaya, Anastasia. Aesthetics, Politics, and Narrative: The Work and Legacy of Playwright Moises Kaufman. Lambda Literary Review, 15 Nov. 2016, lambdaliteraryreview.org/2016/11/aesthetics-politics-and-narrative-the-work-and-legacy-of-playwright-moises-kaufman.

Nassour, Ellis. Michael Emerson’s Journey From Farm Boy to Oscar Wilde. Playbill, 20 Sept. 1997, https://playbill.com/article/michael-emersons-journey-from-farm-boy-to-oscar-wilde-com-101018.

Polini, Emma. The Literary Legacy and Legendary Lifestyle of Oscar Wilde. Aletheia: The Alpha Chi Journal of Undergraduate Research, vol. 2, no. 2, Fall 2017.

Purcell, Carey. I Was Enraged, I Was Saddened - Why Gross Indecency Was Banned in Russia and Will Return to NYC With A Vengeance. Playbill, 30 Sept. 2015, www.playbill.com/article/i-was-enraged-i-was-saddened-why-gross-indecency-was-banned-in-russia-and-will-return-to-nyc-with-a-vengeance.

Wilde, Oscar. The Ballad of Reading Gaol. (1898).

Wilde Takes The Importance of Being Accurate a Little Too Earnestly. The Guardian, 12 Sept. 2012, www.theguardian.com/film/2012/sep/12/wilde-importance-being-accurate-stephen-fry. (review of Wilde 1997).