Norval Morrisseau, an Anishinaabe artist often described as the “Picasso of the North,” profoundly impacted both Indigenous and contemporary art. As the founder of the Woodland School of Art, he developed a distinct style that integrated Anishinaabe cultural symbols with vibrant colors and bold outlines. Morrisseau’s legacy goes beyond his artistic contributions, influencing Indigenous art, promoting Anishinaabe spirituality, and bridging Indigenous narratives with broader audiences.

Morrisseau was born on the Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek reserve in 1932, raised within a traditional Anishinaabe worldview that informed much of his art. Due to family circumstances, he was largely raised by his maternal grandparents, who introduced him to the teachings, language, and spiritual practices central to Anishinaabe culture. Anishinaabe storytelling traditions, rich with creation stories, mythological figures, and teachings on nature, had a lasting impact on him, and his upbringing amidst these teachings provided him with a profound sense of purpose and connection to his heritage (Neufeld 24; Robertson 89).

A turning point in Morrisseau’s life came during his illness in the 1950s, which led him to be initiated into the Midewiwin, a spiritual society among the Anishinaabe. This experience endowed him with deep spiritual knowledge and granted him permission to use sacred symbols, an essential foundation of his art (Robertson 102). His work often drew from these symbols to create a visual narrative that communicated Anishinaabe cultural and spiritual values, such as respect for nature and balance between physical and spiritual realms. The Midewiwin initiation also solidified Morrisseau’s commitment to preserving and sharing Indigenous knowledge through his art.

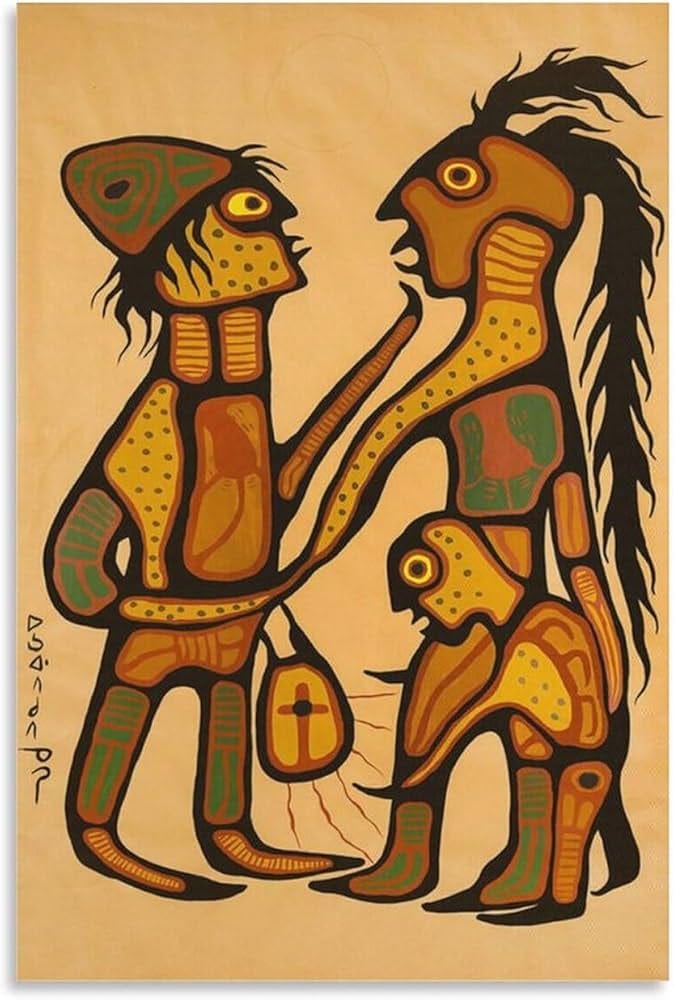

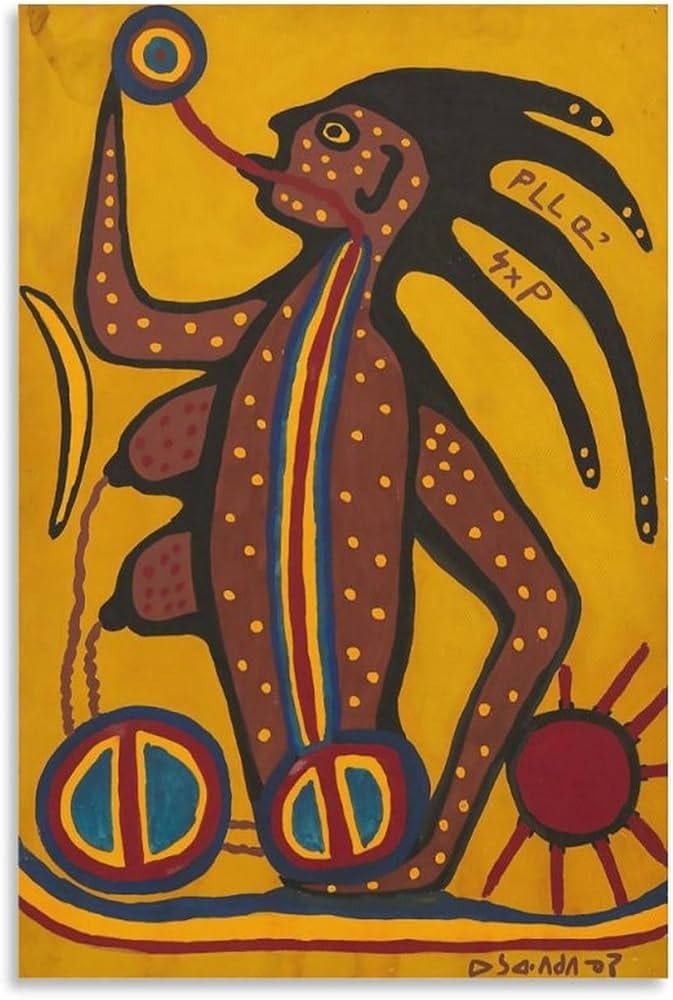

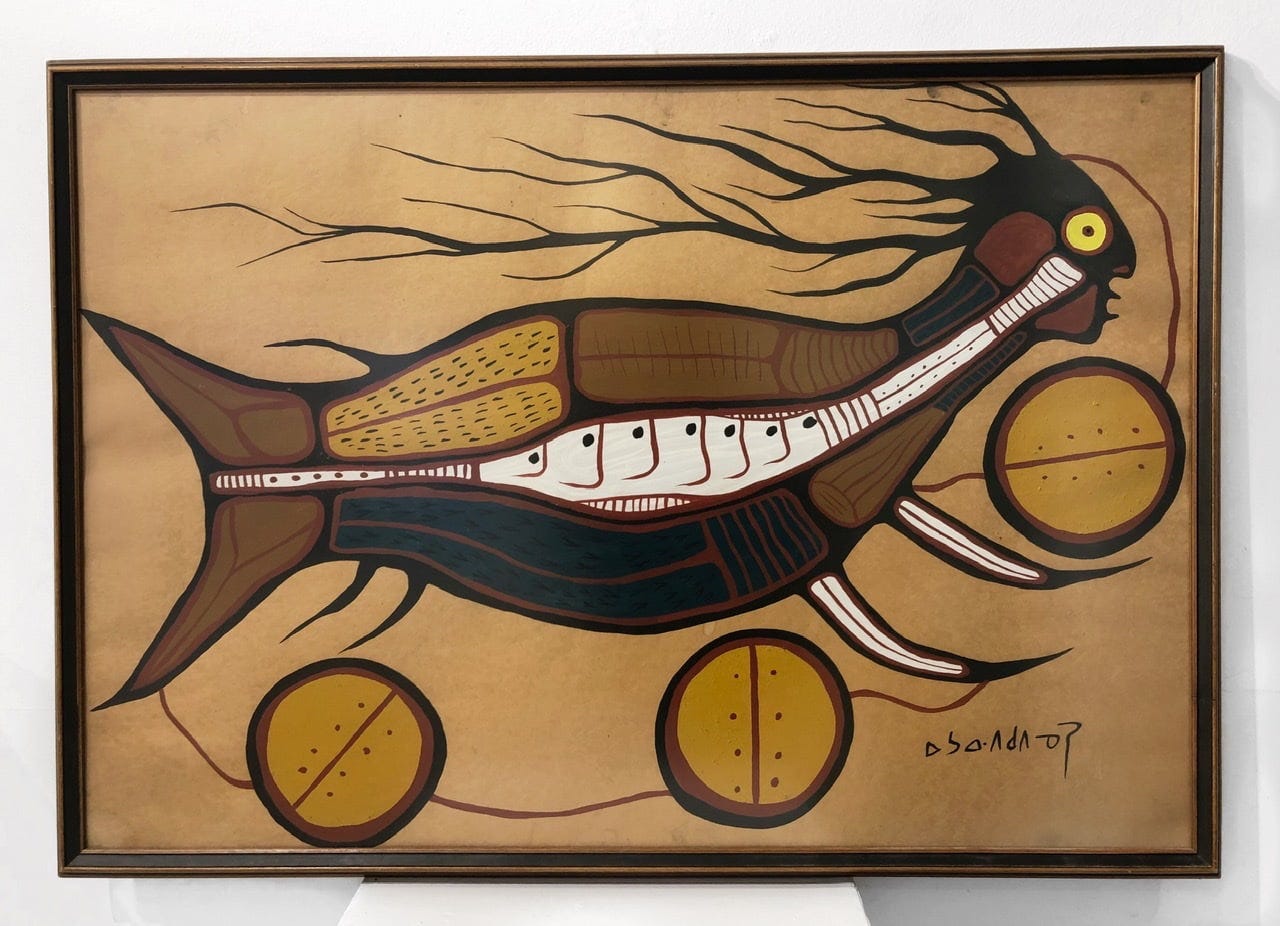

Morrisseau’s work revolutionized Indigenous art, forming what is now known as the Woodland School of Art. His signature style includes the use of thick black outlines, vibrant colors, and symbolic forms that portray spirits, animals, and mythological figures. Morrisseau’s method of depicting internal energy within his figures, often by filling bodies with vibrant colors and intricate patterns, conveys the Anishinaabe belief in the spiritual essence present in all beings (Jojola 43). Through these techniques, Morrisseau created art that was both deeply personal and universal, capturing the attention of Indigenous and non-Indigenous audiences alike.

While Morrisseau drew from Indigenous spiritual and cultural motifs, he also incorporated elements from Western art, such as synthetic paint colors and layered compositions, merging traditional and modern approaches (Neufeld 56). His adaptation of acrylics in particular enabled him to produce highly saturated, brilliant hues that became a trademark of his style. By combining Indigenous themes with contemporary art forms, Morrisseau’s Woodland School created a bridge between Indigenous cultural narratives and Western art appreciation, further establishing the unique presence of Indigenous voices in mainstream art.

Morrisseau’s art often explores interconnected themes of spirituality, mythology, and duality, reflecting his deep understanding of Anishinaabe worldview and teachings. Spirituality is central in his work, with frequent depictions of mythological beings such as Thunderbird and Nanabush, which represent forces of power, change, and protection within Anishinaabe beliefs (Hill 31). These spiritual figures reflect Morrisseau’s belief in the interconnectedness of all life and the power of the natural and spiritual worlds.

Duality is another recurring theme in Morrisseau’s art, underscored by his use of contrasting colors, paired figures, and the representation of both physical and spiritual forms within a single composition. The Anishinaabe philosophy of balance and harmony is evident in these works, which often depict pairs or opposites to represent the need for equilibrium in nature and life (Robertson 138). Morrisseau used color contrasts, such as warm and cool hues, to heighten the visual effect of this duality, which is significant in Anishinaabe cosmology and underscores the coexistence of different, often opposing, forces within the universe.

Social themes also play a crucial role in Morrisseau’s work. His experiences with colonialism, poverty, and addiction gave him a unique perspective on issues facing Indigenous communities, which he expressed through paintings that depict the struggles of his people. Morrisseau’s works about his own battles with addiction provide a raw, honest lens on these challenges, allowing his art to resonate as both a personal and collective story of resilience (McLuhan 33). His willingness to depict such struggles added depth to his work and contributed to the broader narrative of Indigenous resilience and cultural survival.

Norval Morrisseau’s impact on Indigenous and contemporary art is immense. As one of the first Indigenous artists to gain national and international recognition, he broke barriers for Indigenous representation in mainstream art institutions. His contributions were formally recognized with numerous honors, including his induction into the Order of Canada, highlighting his influence on Canadian culture. His retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada further cemented his status as an essential figure in Canadian art, bringing Indigenous perspectives and aesthetic traditions to the forefront of the country’s cultural narrative (Hill 29).

Morrisseau’s Woodland style has inspired multiple generations of Indigenous artists, from contemporaries like Daphne Odjig to younger artists who continue to draw upon his vibrant use of color and symbolic representation. Through his style, Morrisseau advanced a new Indigenous artistic language that communicated Anishinaabe values and spirituality in a way that resonated beyond cultural borders, creating a template for others to express their heritage through modern visual forms.

Morrisseau’s legacy is, however, shadowed by issues of art forgery and legal controversies surrounding the authenticity of his work. Unsanctioned reproductions of his art have circulated widely, leading to disputes over intellectual property rights and questions about the protection of Indigenous art in the commercial art market (Robertson 141). Despite these challenges, Morrisseau’s contributions continue to influence Indigenous art scholarship, while his approach to identity, spirituality, and social issues remains a testament to the power of art as a means of cultural resilience.

Norval Morrisseau’s life and work embody a profound commitment to the preservation and celebration of Anishinaabe culture, providing a bridge between Indigenous and non-Indigenous audiences. His development of the Woodland School of Art not only redefined Indigenous art but also created a space for cross-cultural understanding, giving voice to Anishinaabe spirituality, history, and resilience. Morrisseau’s legacy, marked by both innovation and resilience, remains a powerful testament to the role of art in bridging cultures and affirming identity. His story and artistic influence continue to resonate, inspiring artists and scholars alike to honor the cultural richness of Indigenous traditions while challenging perceptions of contemporary art’s scope and diversity.

References:

Hill, Greg A. Norval Morrisseau: Shaman Artist. National Gallery of Canada, 2006.

Jojola, Ted. The Woodland Style: Norval Morrisseau’s Legacy and Indigenous Art Movements. Journal of Indigenous Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, 2017, pp. 42–58.

McLuhan, T.C. Touch the Earth: A Self-Portrait of Indian Existence. Promontory Press, 1990.

Neufeld, Elaine. Norval Morrisseau: Man Changing Into Thunderbird. Douglas & McIntyre, 2014.

Robertson, Carmen. Norval Morrisseau: Life & Work. Art Canada Institute, 2016.