Mushrooms have long played a significant role in Indigenous cultures across the world, not only as a source of sustenance and medicine but also as profound symbols in art, spirituality, and communal identity. In many Indigenous traditions, mushrooms are seen as sacred tools capable of unlocking divine knowledge, promoting healing, and connecting humans to otherworldly realms.

The depiction of mushrooms in Indigenous art transcends mere botanical representation, exploring a rich tapestry of cultural, spiritual, and symbolic meanings. Across Indigenous traditions, mushrooms are often seen as intermediaries between the earthly and spiritual realms. These fungi, which grow in liminal spaces and decay organic matter, mirror the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth; central themes in many Indigenous belief systems (Hofmann, 2008). Artistic depictions of mushrooms, therefore, reflect their cultural significance, serving as both aesthetic expressions and visual narratives that encode communal knowledge and spiritual traditions.

In cultures where psilocybin mushrooms hold sacred significance, such as among the Mazatec people of Oaxaca, Mexico, these fungi are often portrayed as symbols of divine communication. Psilocybin mushrooms are referred to as the “flesh of the gods” (teonanácatl in Nahuatl), highlighting their revered status as vehicles for spiritual enlightenment (Wasson, 1957). This divine association is reflected in ancient Mesoamerican art, where mushroom imagery appears on carved stone effigies, ceremonial vessels, and murals. For example, the "mushroom stones" found in Guatemala, dating back to the Maya and Olmec civilizations (1000 BCE–500 CE), are believed to symbolize the sacred nature of these fungi, often depicting human or divine figures emerging from or atop mushroom caps (Beltrán, 1995).

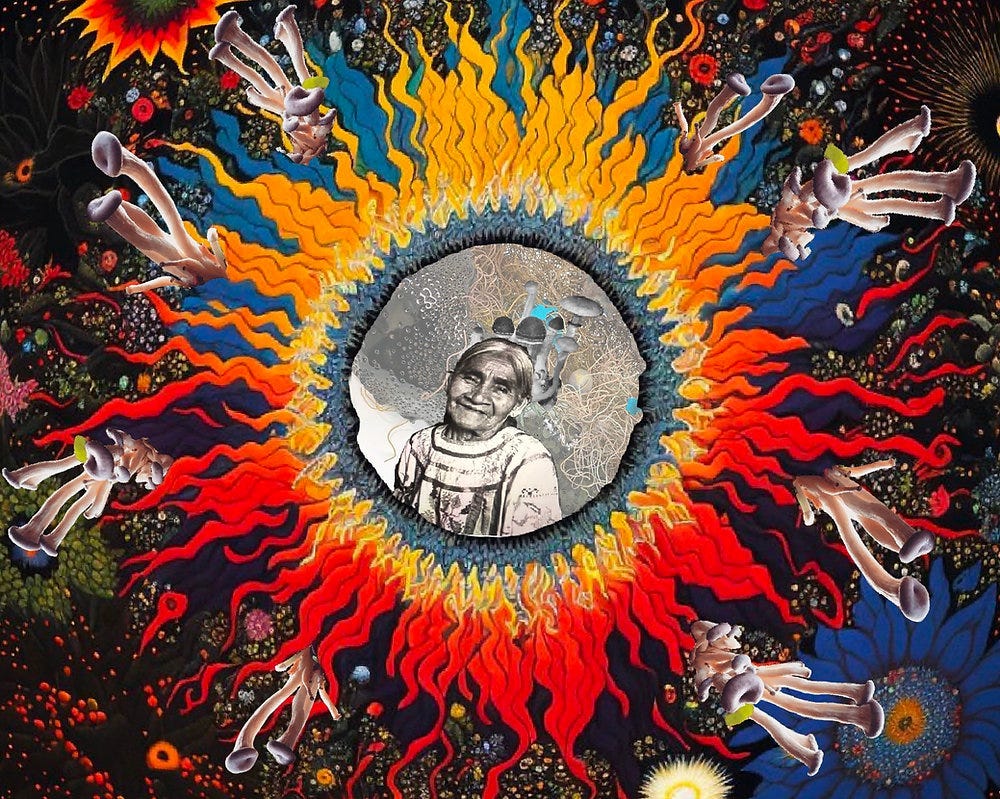

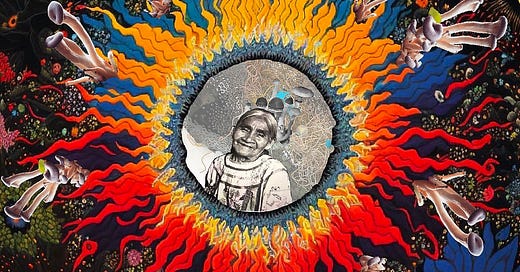

In Mazatec art, the representation of mushrooms integrates vibrant colors and natural motifs, evoking the transcendental visions experienced during psilocybin ceremonies. These visual elements capture the otherworldly experiences facilitated by the fungi, such as communion with ancestral spirits or the perception of interconnectedness within the natural world (Vásquez, 2009). Similarly, contemporary Indigenous artists like Paola Díaz blend traditional aesthetics with modern styles, using mushrooms as metaphors for cultural resilience and spiritual continuity in the face of globalization and cultural homogenization (Díaz, 2016).

Mushrooms also serve as tools for the creation of art within Indigenous cultures. The ceremonial use of psilocybin mushrooms often inspires the production of visual art during or after the ritual. Participants may depict their visions through painting, carving, or embroidery, translating the ineffable into tangible, visual forms. Such artworks act as spiritual artifacts, preserving the ceremonial experience and offering guidance for future generations (Garcia, 2005).

In addition to visual depictions of mushrooms, they feature prominently in ceremonial regalia. Some Indigenous cultures adorn garments, headdresses, and ceremonial objects with embroidered or painted mushroom motifs to honor their sacred role. These adornments elevate the aesthetic value of the items and imbue them with spiritual significance, marking the wearer as a participant in sacred rites (Shlain, 1991).

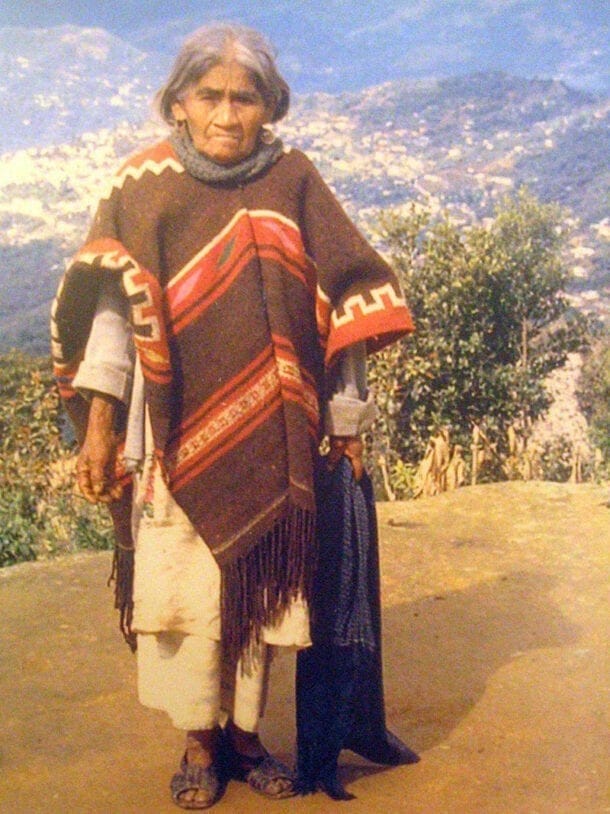

Among the Mazatec people, psilocybin mushrooms play an essential role in healing ceremonies known as veladas, typically conducted at night, where the healer and their patients enter trance-like states to seek divine guidance. The mushrooms are referred to as niños santos (holy children) and are consumed to achieve heightened spiritual awareness and insight into both physical and emotional ailments (Vásquez, 2009). María Sabina, a revered curandera, was renowned for her ability to communicate with the spiritual realm through the consumption of psilocybin mushrooms.

Born in 1894 in rural Oaxaca, María Sabina was initiated into the practice of curanderismo (healing) at an early age. Her spiritual calling was marked by dreams and visions, which she interpreted as messages from the spirits urging her to take on the role of healer (Garcia, 2005). Sabina’s expertise in using psilocybin mushrooms was integral to her healing practice, which addressed both physical and spiritual ailments, including personal suffering and social injustices faced by her community (Wasson, 1957).

Sabina’s healing ceremonies were deeply spiritual, involving not only the consumption of mushrooms but also the singing of curandera chants known as ícaros, which helped guide participants through their visions (Wasson, 1957). These rituals were central to Sabina's role as a healer, enabling her to connect with spirits and gain insights into the causes of illness.

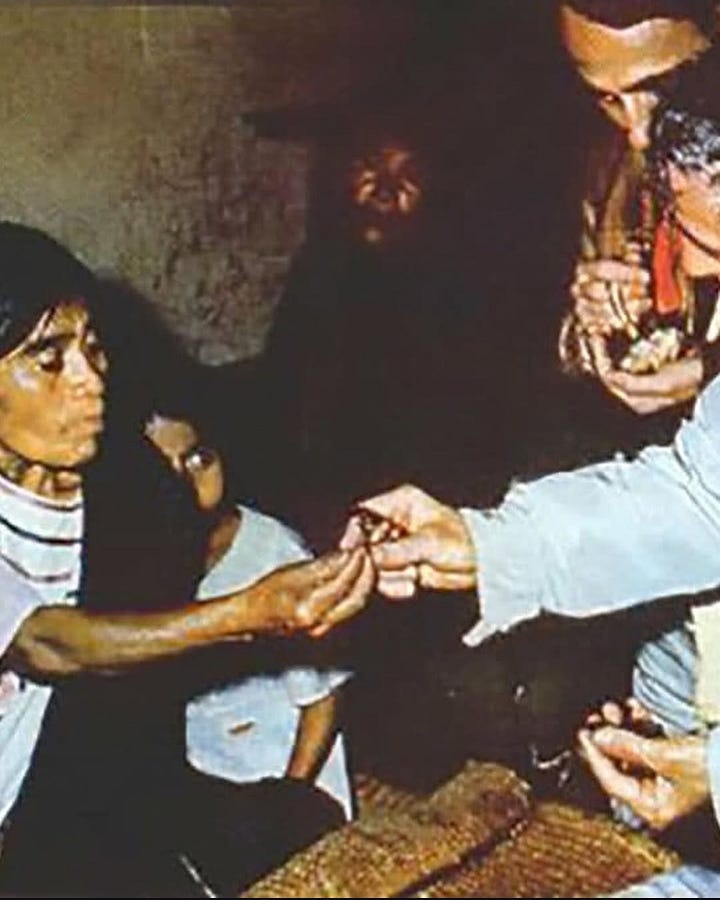

Sabina’s fame outside the Mazatec region began in the 1950s when the American ethnobotanist R. Gordon Wasson and his wife, Valentina, traveled to Oaxaca in search of teonanácatl. Wasson participated in one of Sabina’s velada ceremonies in 1955, and his article, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” published in Life magazine in 1957, introduced Sabina and the sacred use of psilocybin mushrooms to a global audience (Wasson, 1957). This marked the beginning of a wider Western interest in psychedelic substances, including mushrooms.

While the article brought international attention to Sabina’s practices, it also led to exploitation and commodification. As Western interest in psychedelic mushrooms grew, more people traveled to Oaxaca to experience Sabina’s ceremonies, often without respect for their spiritual context. This influx of outsiders disrupted the sacred traditions, with some visitors treating the mushrooms as recreational substances rather than as spiritual tools (Garcia, 2005).

Sabina expressed mixed feelings about the attention her practices received. While she was not opposed to sharing her knowledge with outsiders, she became frustrated with the commercialization of her sacred rituals. In interviews, she lamented that the spiritual essence of her practices was being distorted, as many of the foreigners who came to her village sought personal pleasure rather than spiritual enlightenment (Garcia, 2005).

Despite the exploitation of her practices, Sabina’s legacy continues to inspire both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. Her work has influenced contemporary research into the therapeutic use of psilocybin mushrooms, particularly in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. In recent years, psilocybin has been studied as a treatment for conditions such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and Sabina is often cited as a foundational figure in bridging the gap between Indigenous healing practices and modern therapeutic applications (Carhart-Harris, 2018).

Sabina’s impact extends beyond the realm of psychedelic research, inspiring Indigenous artists and spiritual leaders to reclaim and preserve their sacred traditions. Her legacy serves as a reminder of the resilience of Indigenous knowledge systems and the importance of cultural respect in the face of external pressures (Vásquez, 2009).

Mushrooms hold a profound place in Indigenous art and spirituality, particularly within the Mazatec culture, where they are viewed as sacred tools for healing and spiritual growth. The artistic depictions of mushrooms serve not only as representations of these fungi but also as expressions of cultural identity, spiritual connection, and ecological wisdom. María Sabina’s use of psilocybin mushrooms has had a lasting impact on both Indigenous and global understandings of plant medicine. While her work was complicated by Western appropriation and commercialization, her legacy endures, serving as a symbol of the intersection between Indigenous knowledge and the broader psychedelic movement. As interest in psychedelic therapy continues to grow, Sabina’s story underscores the importance of respecting the cultural context in which these practices originated.

References

Wasson, R. G. (1957). Seeking the Magic Mushroom. Life Magazine.

Vásquez, V. (2009). Mushrooms and the Mazatec: An Exploration of Art and Spirituality. Cultural Anthropology Review, 30(3), 67–82.

Garcia, C. (2005). Healing and the Spirit: The Role of María Sabina in Mexican Medicine. Anthropological Journal of Mexican Culture, 32(4), 78–91.

Beltrán, S. (1995). Mushroom Stones of Mesoamerica: Ancient Art and Divine Knowledge. Journal of Mesoamerican Studies, 24(3), 45–56.

Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2018). The Therapeutic Potential of Psilocybin. Psychopharmacology, 235(3), 653–661.

i can’t express my thanks for this enough goddess….thank you thank you thank you

So lovely that you have created this work about her! 🍄