Moroccan art and architecture are celebrated for their fusion of ornamental craft, urban design, and modern innovation. Building upon the dynastic and typological groundwork laid in Part One, this explores how Morocco’s built environment is enriched by intricate decorative arts, distinctive city planning, and contemporary expressions that together give Moroccan architecture its singular character. From the glimmer of hand-cut tiles in an ancient courtyard to the silhouette of a modern mosque on the skyline, each layer of design in Morocco reflects a dialogue between past and present.

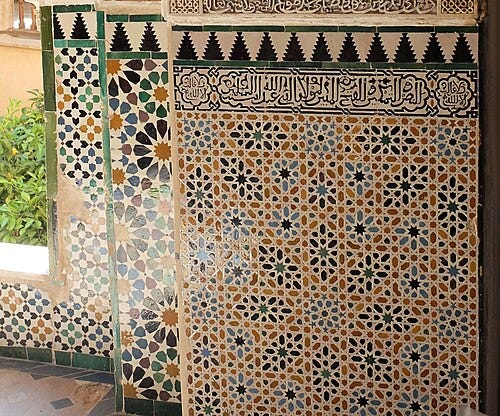

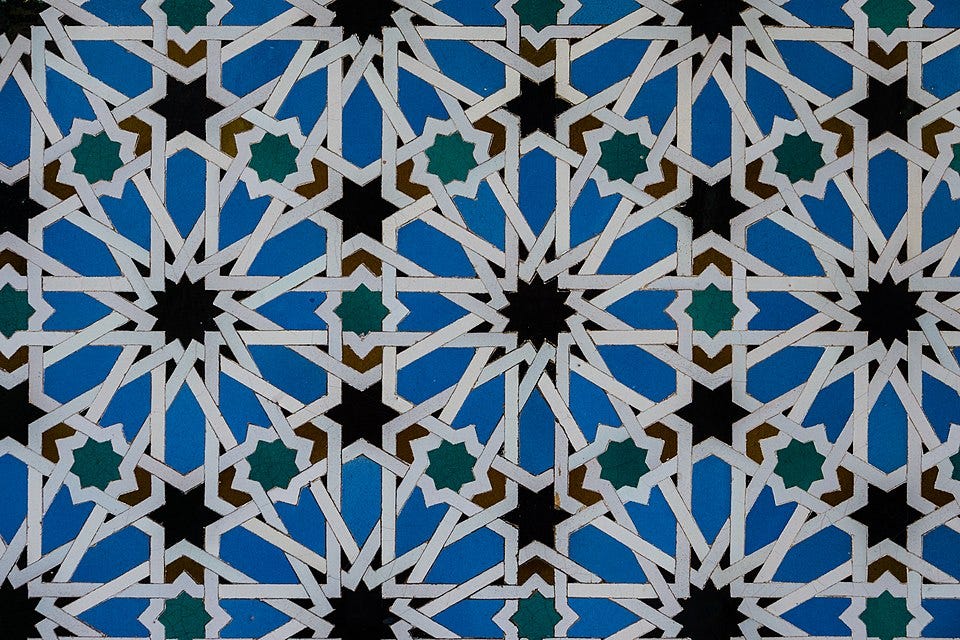

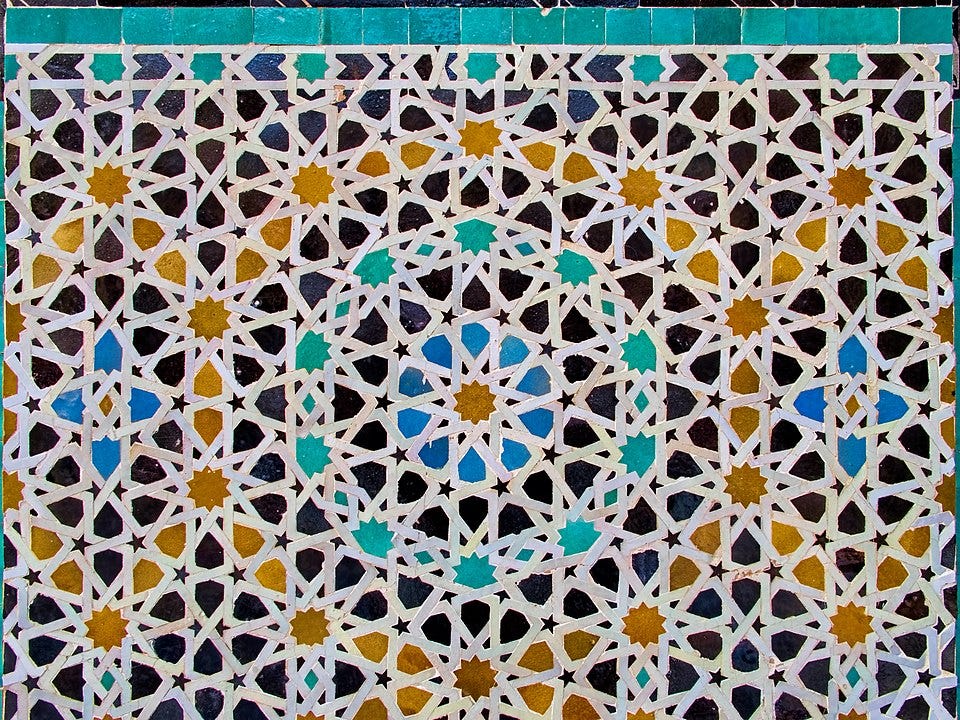

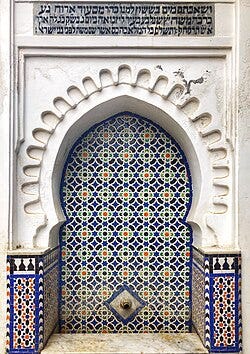

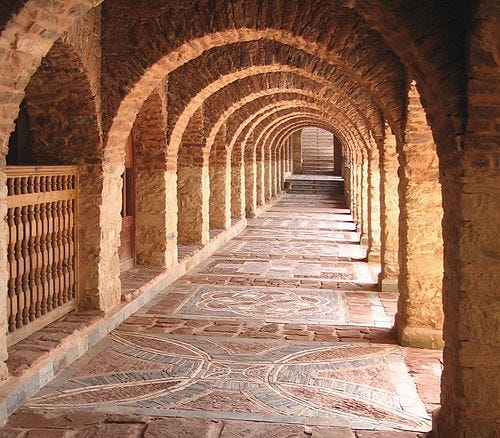

Morocco’s architecture is inseparable from its rich decorative arts. Zellige (zillīj) is the iconic mosaic tilework of Morocco, composed of individually chiseled tiles fitted into complex geometric motifs. Its repetitive star-like patterns and interlaced designs, often covering fountains, mihrab walls, and palace courtyards, symbolize the infinite and divine unity in Islamic art. Dynastic patrons like the Marinids popularized zellij in the 14th century, using it in madrasas and mosques to create kaleidoscopic mosaics that draw the eye inward in contemplation.

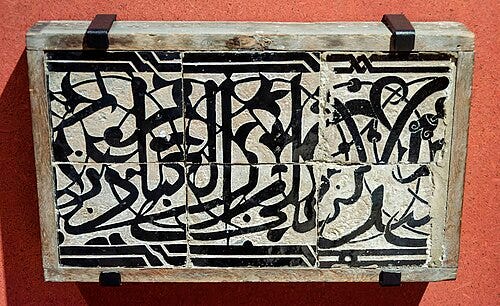

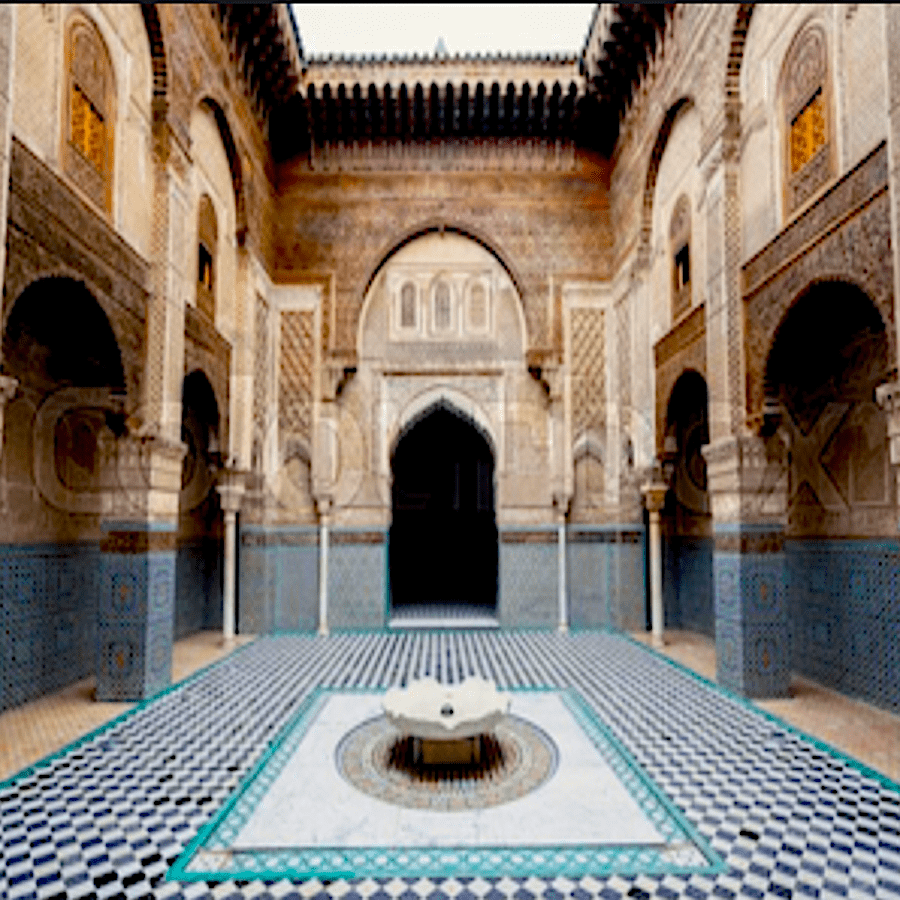

Alongside geometry, Moroccan ornamentation features arabesques,flowing vegetal and floral motifs, often intertwined with Arabic calligraphic bands. In Moroccan madrasas such as the Bou Inania in Fez, surfaces are structured in registers: zellij tiles at the base, a middle frieze of carved or painted calligraphy, and above that, finely carved stucco full of arabesque tendrils. Quranic verses and pious phrases, rendered in elegant Maghribi script or cursive naskh, grace doorways and cornices, literally “inscribing” faith into architecture. These inscriptions and vegetal patterns transform structural elements into canvases of devotion and craftsmanship, exemplifying the Islamic maxim that calligraphy is the geometry of the spirit.

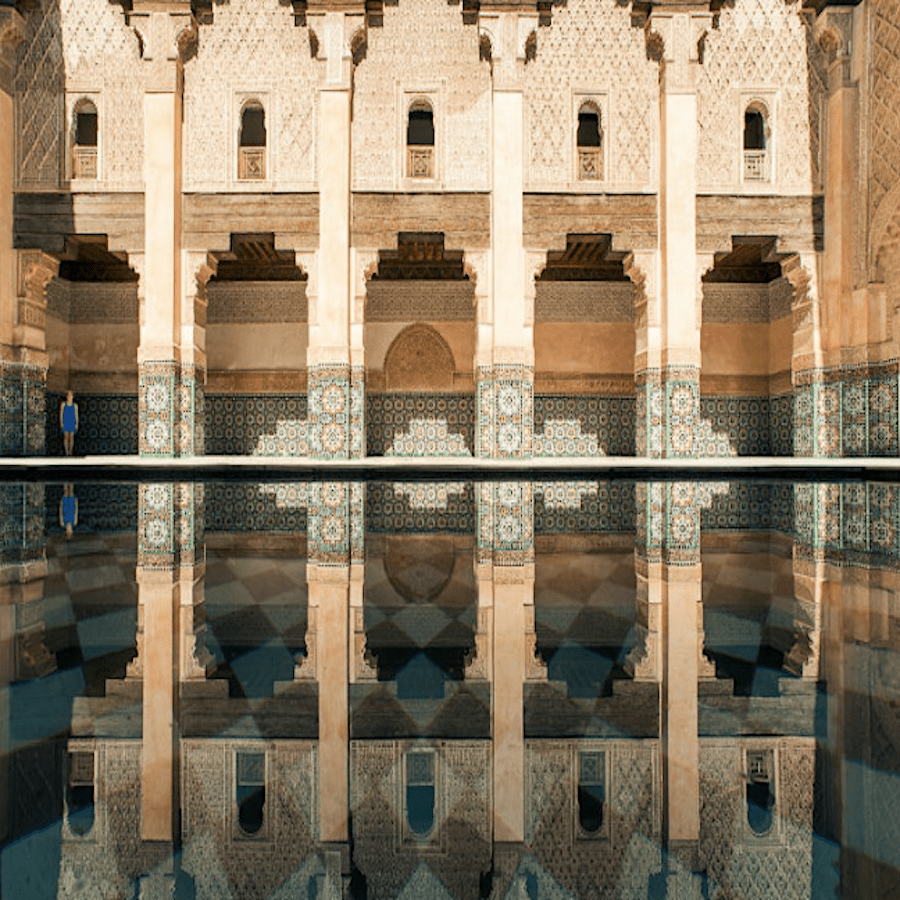

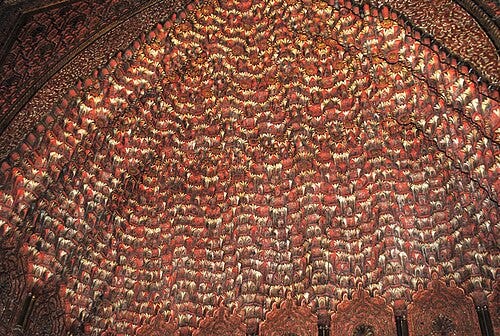

Moroccan artisans also achieved mastery in carved cedar wood and carved plaster (stucco, or gebs). Historic city gates and mosques feature doors of Atlas cedar inlaid with interlacing star patterns and arabesques. Ceilings of palaces and madrasas, such as the 16th-century Saʿadian pavilions, boast gilded cedar berchka panels and muqarnas (stalactite) wood cornices. Equally exquisite are the stucco friezes and vaults, where craftsmen chiseled plaster into lace-like screens of scrolls and tessellations. The muqarnas technique, introduced in the 12th century Almoravid period, became a hallmark of Moroccan interiors, seen in the honeycomb vaults of the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh, for example. The decorative traditions of Morocco, from zellij to carved wood and stucco, create a visual refrain of “horror vacui” (fear of empty space), ensuring that every surface carries meaning and beauty.

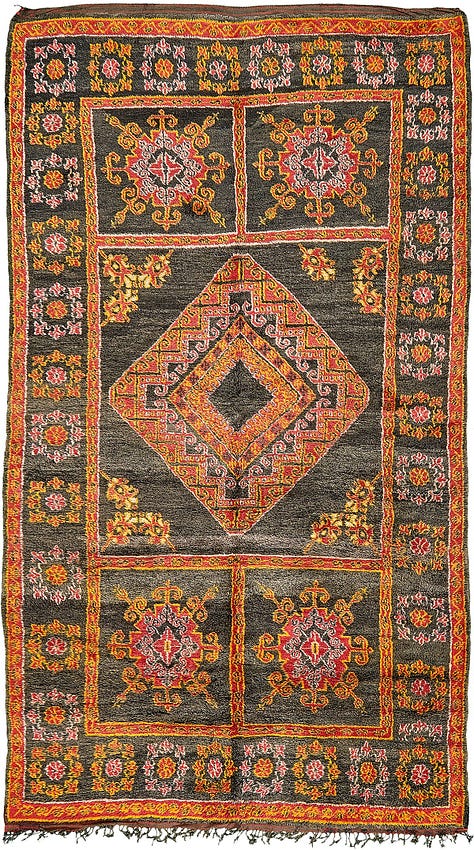

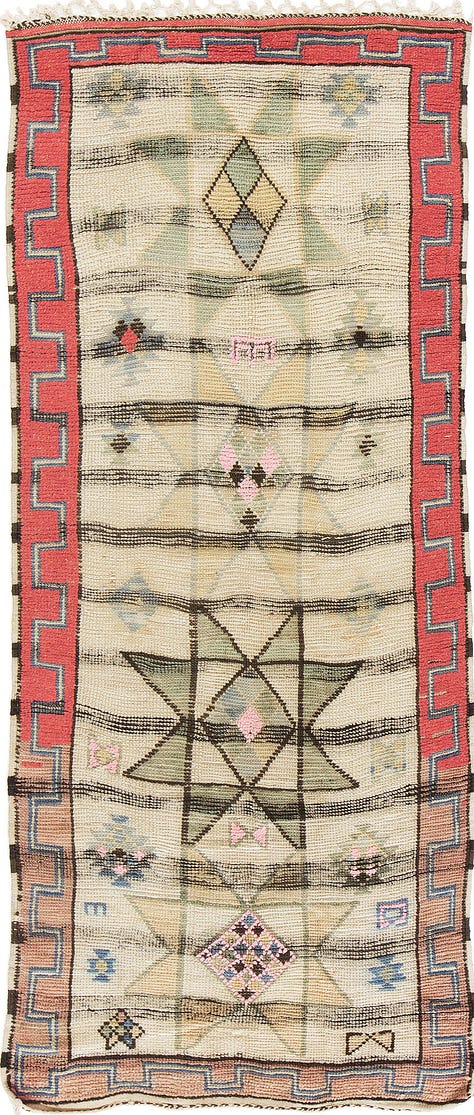

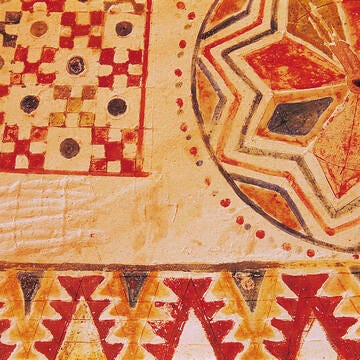

Beyond architecture, Morocco’s artistic heritage thrives in its decorative crafts. The city of Fez has been a center of pottery for centuries, famed for its distinctive cobalt-blue and white ceramics. Fez potters use a white tin glaze and complex hand-painting techniques, often featuring arabesque vines, geometric trelliswork, or calligraphic medallions. Functional wares like plates, tajines, and vases double as artworks, preserving aesthetic traditions from Moorish times. The techniques, shaping local clay, sun-drying, firing in kilns fueled by olive pits, remain largely unchanged, and Fez’s master ceramists continue to produce the glazed tiles (used in zellij) and pottery that have decorated Moroccan interiors since the medieval era. Safi and Meknes are other notable pottery centers, but Fez’s fakhkharin (potters) are especially celebrated for the quality of their glazes and the refinement of their motifs. In Morocco’s woven arts, Berber and Arab traditions intersect to produce rich textiles. Tribal Berber carpets, often woven by women of the Middle and High Atlas, feature bold geometric motifs that encode cultural narratives. These rugs, whether the thick-piled, monochrome Beni Ourain carpets of the Atlas or the brightly colored flat-weave kilims of the Middle Atlas and Anti-Atlas, often incorporate diamonds, zigzags, and lozenges that signify protection, fertility, and community. Each region and tribe has its hallmark palette and pattern: the reds and oranges of Ouarzazate versus the blacks and creams of the Beni Ourain, for example, reflect both environment and heritage. Similarly, urban weaving traditions survive in places like Fez and Rabat, where craftspeople produce brocaded silks and wool embroideries. Traditional Moroccan textiles, from the luxurious silk brocade of Fez (used historically in palace furnishings and ceremonial garments) to the humble woolen hanbel blankets of the High Atlas , all carry forward geometric and arabesque motifs that echo those found in architecture, thus creating a unified artistic language across media.

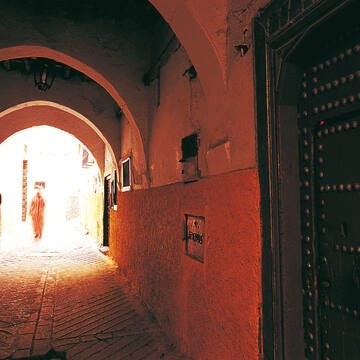

Morocco’s historic cities (medinas) are masterpieces of human-scale urban design, balancing communal life with privacy. The medina is typically a dense warren of narrow alleys and cul-de-sacs opening onto unexpected public squares or courtyards, a layout that slows down movement and fosters social interaction. Within these labyrinthine medinas, such as those of Fez and Marrakesh, everyday life unfolds in a network of specialized souks (markets), e.g. the copper-smiths’ street, the spice market, the leather tannery quarter, each nestled in twisting lanes. The souk streets often lead to communal nodes; a sunlit square, a major mosque, or a city gate. Crucially, even as medinas teem with commerce and public activity, the residential fabric maintains privacy: traditional houses (riads and dars) present nearly blank walls to the street and turn inward to hidden courtyards. This inward-facing design, with high walls and few exterior windows, reflects social values of privacy and family security in Islamic society. Inside the homes, life centers around a courtyard garden (often with a fountain), while the narrow exterior alleys ensure cool shade and minimal intrusion.

Throughout the medina, certain civic structures anchored daily rituals. Sabils (street-side fountains) provided water for drinking and ablutions; many are framed by ornate zellij and carved wood canopies as pious gifts from past patrons. Equally important were the hammams (public bathhouses), often unassuming from outside but crucial as cleansing and social spaces for the community. The medina of Fez, for example, still contains dozens of historic hammams and fondouks (inns for merchants), each serving both a practical function and a social one.

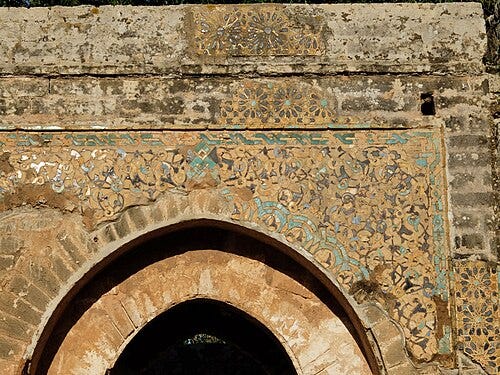

Medinas are typically enclosed by ramparts with monumental gates (bab). These city walls, such as the circa-12th century walls of Marrakesh or Fez, regulated movement in and out of quarters and were often closed at night for security. Their gates were not merely defensive apertures but also ornamental triumphal arches bearing Kufic inscriptions and geometric ornament (e.g. Fez’s Bab Bou Jeloud or Rabat’s Bab er-Rouah from the Almohad era). The effect of these walls and serpentine gates was to create a defined boundary between the chaotic vibrancy of the medina and the surrounding land, reinforcing the medina’s identity as a world unto itself. Notably, the medinas of Fez, Marrakesh, Tetouan, and others are today UNESCO World Heritage sites, recognized for preserving this ancient urban fabric where “the majority of original functions and lifestyle persist”. In these historic cores, one experiences an urbanism designed for foot traffic and social cohesion, a sharp contrast to modern grid cities, and yet this very human-scale design proves remarkably sustainable and resilient over centuries.

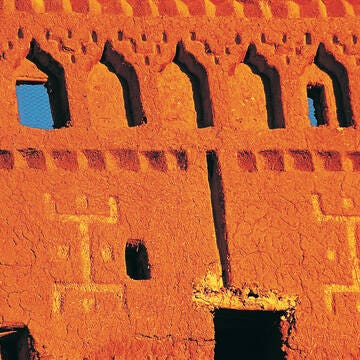

In Morocco’s arid and frontier regions, architecture evolved to meet the demands of defense, communal storage, and climate. The Saharan and Atlas zones are dotted with ksour (fortified villages) and kasbahs (fortified great houses), which illustrate a vernacular response to tribal conflict and harsh environments. Constructed primarily of rammed earth (tabia) or mud-brick, these structures blend into the tawny landscape, yet captivate with their sculptural forms. A prime example is the Ksar of Aït-Ben-Haddou, a UNESCO-listed settlement in southern Morocco’s Ounila Valley. Aït-Ben-Haddou is a collective fortified village of tower-houses built against a hillside, all encircled by defensive walls reinforced with corner towers and a single baffle-gate entrance. The earthen houses within range from modest dwellings to taller “mini-citadels” with high angle towers; notably, the upper facades of many houses are embellished with decorative clay-brick motifs and crenellations, bringing an artistic touch to otherwise austere architecture. Such motifs, serrated merlons, patterned friezes in mud, echo the interior decorative traditions (geometric and floral designs) albeit rendered in humble clay. These pre-Saharan strongholds were not only dwellings but also contained community structures. Aït-Ben-Haddou, for instance, had a mosque, caravanserai, public square, and an agadir (fortified granary) on a hill for storing grain securely. Agadirs were common in Berber regions; fortified communal granaries with thick walls and locked storage cells, often perched on hilltops, symbolizing the collective security of the tribe’s food supply. Many agadirs and tighremt (fortified manor houses) feature simple exterior ornament like painted symbols or carved mud reliefs, showing that even in defense, aesthetic expression found a place. The kasbah, typically a fortified residence of a local chieftain, is another hallmark: for example, the Kasbah Taourirt in Ouarzazate or Kasbah Amridil in Skoura are multi-story earthen castles with multiple towers and interior courtyards. Their thick walls, few small windows, and corner bastions were practical against attack and insulation against heat, yet interior spaces could be richly decorated with painted wooden ceilings and plaster niches. A distinctive feature of these kasbahs is the “merlon” crenellation and clay sculpture atop their walls, forming horizontal zig-zag patterns against the sky. While functional as battlements, these crenellations often assume decorative rhythms, effectively integrating ornament into military architecture. In Morocco’s far south, even granary-fortresses like Igoudar (plural of agadir) exhibit this mix of utility and ornament: solid exterior walls hide vaulted storage inside, while their entrances might display carved symbols of protection. Collectively, Morocco’s desert architecture shows an adaptation to scarcity; using local earth and wood, maximizing thermal mass for cool interiors, and creating multi-purpose fortifications that were at once homes, forts, and communal treasuries. Their enduring silhouettes, the reddish mudbrick towers of Aït-Ben-Haddou glowing at sunset, speak to a heritage where necessity and artistry coalesce. The ksar of Aït-Ben-Haddou in southern Morocco, a 17th-century fortified village (qsar) built from rammed earth. Its clustered kasbah-houses with corner towers and crenellated clay parapets exemplify pre-Saharan earthen architecture.

One of the most significant influences on Moroccan art and architecture came from Al-Andalus (medieval Muslim Spain). The fall of Granada in 1492 triggered an exodus of Muslims (and Jews) to North Africa, and many skilled artisans, architects, and intellectuals settled in Morocco. This influx of Andalusian craftsmen catalyzed a fusion of Hispano-Moorish aesthetics with indigenous Moroccan (Berber) building traditions. Historically, there had already been interchange; the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties (11th–13th centuries), based in Morocco, also ruled parts of Spain and imported Andalusi styles, creating a “definitive ‘Hispano-Moorish’ or Andalusi-Maghribi style” that would become the hallmark of Moroccan architecture. For instance, the Almoravid Sultan commissioned a splendid minbar (pulpit) from Cordoban artisans for a mosque in Marrakesh, illustrating cross-continental artistic sharing. After 1492, however, the scale of influence deepened; entire neighborhoods and towns were (re)built in the Andalusian style. The northern city of Tétouan is a prime example, deserted after war in the 15th century, it was rebuilt and “populated by Granadine refugees” led by Sidi al-Mandri, who recreated a little Granada with whitewashed houses, tiled patios, and orchards. To this day, Tétouan’s medina (a UNESCO site) is noted for its Hispano-Moorish layout and ornament, from its delicately carved stucco to its green-tiled roofs, all hallmarks of Andalusi design transplanted to Morocco. Likewise, the Andalusiyyin Quarter of Fez (named for 9th-century Andalusi settlers and enlarged by later waves) is distinguished by its Andalusian-style mosque and fondouks, and the very institution of the Andalusian garden-courtyard (riad) in Moroccan homes may owe much to migrants from Spain who carried on the tradition of courtyard gardens like those of the Alhambra. In royal architecture, the Andalusi impact is evident in the refinement of decoration; the Saadian Dynasty’s 16th-century palaces in Marrakesh, such as the famous El Badiʿ Palace, were explicitly patterned after the Alhambra in Granada.

Contemporary chronicles and modern analysis note that the Badi’s vast courtyard with a central pool, flanking gardens, and pavilions closely mirrored the Court of Lions in layout, albeit at a grander scale, and its sumptuous decor (zellij pavements, carved stucco, painted cedar ceilings) emulated the lost palaces of Andalusia. This Hispano-Moroccan synthesis yielded what one scholar calls “an art of living” that combined Berber structural forms (like the robust earthy kasbah) with Andalusian finesse (like glazed tile mosaics and elegant courtyards). Coastal cities such as Chefchaouen, Rabat, and Salé also absorbed many Andalusi families, visible in details like the tiled courtyard houses of Chefchaouen’s old quarters (the city was actually founded by exiles from Granada in the 15th century). Even in religious architecture, the refugees brought expertise, e.g., the Andalusian Mosque of Fez was embellished by artisans proficient in the sophisticated tile and stucco techniques of Cordoba and Seville. The Hispano-Moorish fusion in Morocco is a legacy of both political history and cultural receptivity: expelled from Iberia, master craftsmen found new patrons in Morocco, where they “grafted refined tiles, fountains, and gardens onto Berber building traditions,” producing a Renaissance in Moroccan art in the late 15th and 16th centuries. This fusion is most vividly seen in the elegant medinas of northern Morocco and the enduring Andalusian aesthetic in everything from music to interior design in the kingdom.

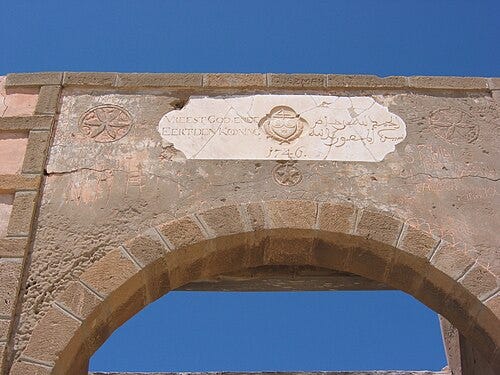

Morocco’s Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts gave rise to port cities whose architecture diverged from interior traditions, adapting to maritime trade and European influence. Essaouira (Mogador) on the Atlantic is exemplary: founded in the 1760s by Sultan Sidi Mohammed ben Abdallah as a new port, Essaouira was designed by a French architect, Théodore Cornut, resulting in a unique grid-patterned medina enclosed by robust seawalls. Unlike the maze-like imperial medinas, Essaouira’s old city has a relatively orthogonal street layout with two major axes intersecting at a central square (the Souk Jdid), reflecting an early modern attempt at formal town planning. Low-rise houses line these straight streets, their facades often lime-washed white with blue painted doors and shutters, a picturesque style that echoes both Portuguese colonial towns and Andalusian coastal villages. The city’s defining features are its fortifications; the Sqala of the Port and Sqala of the Medina, two seafront artillery bastions built by Cornut using European military engineering principles (Vauban-style angled bastions, crenelated platforms for cannons). These bastions, with rows of bronze cannons still overlooking the Atlantic, embody the blend of defense and commerce; they guarded the harbor while impressing visiting traders. Many coastal towns similarly feature forts or borj built by Moroccans or earlier by Portuguese occupiers (e.g. El Jadida’s 16th-century Portuguese cistern and ramparts). Essaouira’s cityscape also includes a ceremonial gate on the harbor (Bab al-Marsa) and a regular street network dividing quarters for merchants of different nations (Jews, Europeans, locals). The coastal climate and international trade influenced architecture; houses in Essaouira have flat roofs (catching ocean breezes), often with parapets where residents could catch cool air, and they were among the first in Morocco to feature glazed windows (an import from Europe). Further south, Agadir was another important port, rebuilt in modernist style after a 1960 earthquake, but its memory of a coastal kasbah (Agadir Oufella) perched above the bay lives on; that 16th-century kasbah had massive ramparts and offered refuge for the city, showing the persistent importance of fortified highpoints near the sea. Northern Atlantic cities like Asilah and Larache, and Mediterranean Tangier, also show a mix; white-and-blue Andalusian-style houses within Portuguese or Spanish-built bastions. These whitewashed facades and grid-planned new towns arose especially during the 19th and early 20th centuries when European powers built diplomatic quarters or when the French Protectorate established villes nouvelles adjacent to medinas. For example, the French laid out a modern port and boulevards in Casablanca, but even earlier, in the 18th century, Moroccan coastal fort architecture had absorbed European ideas. The result in cities like Essaouira is an environment where “European and Moroccan town-planning models” met in symbiosis; rational street grids and bastions on one hand, and Islamic medina life and indigenous building techniques on the other. Coastal architecture also responded to maritime climate; thick walls to protect against storms, and often a horizontal profile (Essaouira’s skyline is famously low except for its mosque minarets and church towers). Morocco’s port cities developed a hybrid architectural identity, part Medina, part European fortress-town, illustrating how mercantile exchange and colonial pressures created new urban forms. They stand as gateways where Morocco’s interior architectural language was trimmed to meet the sea and the world beyond.

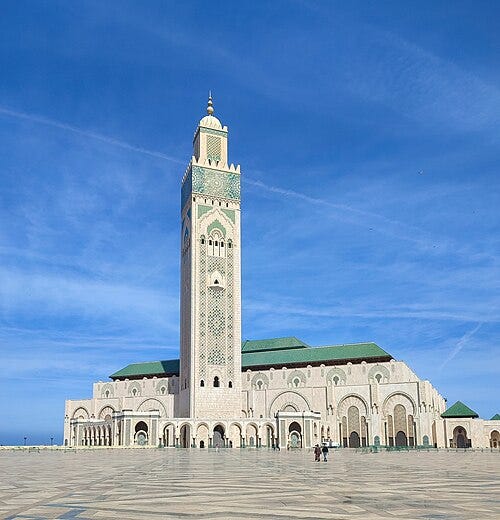

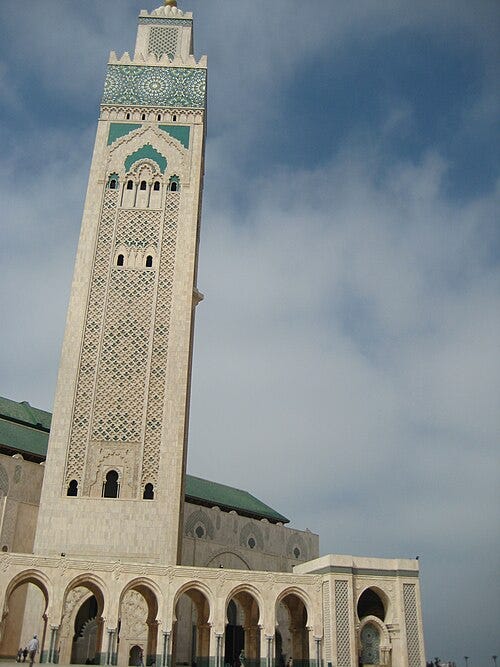

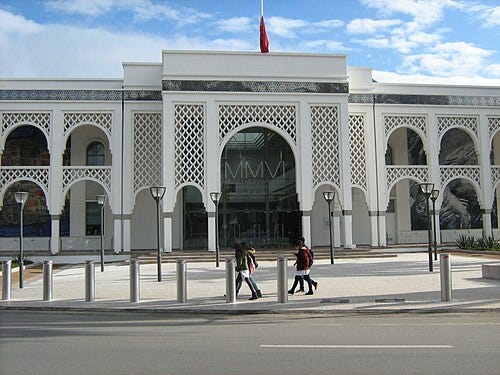

Since Morocco’s independence in 1956, architects have continually sought to bridge modernity with tradition, re-engaging historic forms in new projects. The late 20th and 21st centuries have seen a conscious revival of Moroccan motifs in contemporary architecture, a trend encouraged by both national pride and practical climate responsiveness. One monumental example is the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca (completed 1993), which stands as a modern engineering feat infused with traditional Moroccan design. Commissioned by King Hassan II and designed by architect Michel Pinseau, it was built using contemporary techniques (e.g. laser alignment, retractable roof) but showcases the full vocabulary of classical Moroccan ornament on an unprecedented scale. The mosque’s minaret soars 200 meters high, the tallest in the world, yet is a traditional square form embellished with geometric darj-wa-ktaf motifs and crowned by a lantern, following Maghrebi convention. Tens of thousands of Moroccan artisans were employed to hand-carve the cedar ceilings, chisel stucco, and assemble zellij mosaics across 172,000 square meters of surfaces. The result is a structure that “combines traditional Moroccan design with modern technology”, for instance, the vast prayer hall features marble floors and muqarnas-decorated capitals crafted in Fez, beneath a roof that can retract electronically to open the space to the sky. In the Hassan II Mosque, intricate Quranic calligraphy and arabesque tilework coexist with contemporary elements like glass floors (allowing worshippers to see the ocean below) and electric doors, epitomizing the ethos of innovation within tradition. Beyond such landmark projects, Moroccan architects and international firms have drawn inspiration from heritage as they design new civic buildings, resorts, and cultural centers. A notable theme is the reinterpretation of the riad (courtyard house) and patio in modern programs. Luxury hotels and public buildings often center around enclosed courtyards or atria that echo the cooling, light-filled patios of traditional medinas, a design both aesthetic and climatic. For example, the Mohammed VI Museum of Modern Art in Rabat (2014) reimagines traditional Mashrabiya screens and geometric motifs on a contemporary facade, embedding modern functionality within a recognizably Moroccan skin. Likewise, new university campuses and embassy buildings frequently incorporate horseshoe arches, zellij murals, or green-tiled roofs as postmodern callbacks to historical styles. This trend reflects what scholars note as a deliberate quest for architectural identity; Morocco’s contemporary architecture “increasingly asserts its identity by drawing from traditional forms,” breaking away from anonymous International Style modernism and creating something regionally grounded. We see this in projects like the Royal Mansour Hotel in Marrakesh (opened 2010), where multiple small courtyard riads were built to serve as guest villas, essentially a modern qasr composed of riads, showcasing handcrafted decor by local artisans. Similarly, architects Rachid Andaloussi and others, in designing new governmental buildings, have incorporated modern interpretations of the mashrabiya (lattice screen) to reduce sunlight and reference Islamic design. Contemporary eco-friendly architecture in Morocco also mines tradition: the use of tadelakt plaster and natural ventilation in modern villas, or the reinvention of the wind-catching tower (seen traditionally in hot regions) to cool new offices in Casablanca, indicate a full-circle return to indigenous knowledge.

Moroccan modern architecture is characterized by a selective revival of historical elements, not as pastiche, but as a sustainable and identity-rich design language. As one recent analysis observes, contemporary Moroccan architecture is a fusion of “traditional Berber and Arab-Muslim architecture, both in form and aesthetics,” generating new forms enriched by craftsmanship. The endurance of courtyard typologies and ornamental detailing in new construction demonstrates that far from being relics, Morocco’s architectural traditions continue to evolve and inspire in the modern era.

From the smallest glazed tile to entire city plans, Moroccan art and architecture speak in layers of time and meaning. The decorative traditions (zellij, arabesque, calligraphy, wood and stucco carving) provide a visual grammar that has adorned mosques and palaces for centuries, symbolizing spiritual and cultural ideals in tangible form. Urbanistically, the medina pattern shows an intuitive genius for human-scaled living, integrating privacy, community, commerce, and faith within a cohesive fabric that has proven resilient across a millennium. In parallel, the architecture of deserts and coasts reveals how Moroccans ingeniously responded to environment and historical circumstance, whether through fortified granaries in the Atlas or European-inspired port cities on the Atlantic. Crucially, these diverse threads were never isolated; the influx of Andalusian artisans, the patronage of sultans who valued both local and imported talents, and the continuity of Berber craft traditions all wove together to create Morocco’s distinctive architectural tapestry. Today, as modern architects design the nation’s future, they do so in dialogue with this rich heritage. The persistence of courtyard-centered designs, the use of traditional motifs in avant-garde structures, and the pride in restoring historic monuments all attest that Morocco’s built heritage is a living, dynamic continuum. Moroccan architecture, in sum, is not a static museum of the past but a conversation across time; a dialogue between past and present in which each generation adds new chapters. Ornate or minimalist, earthen or high-tech, Moroccan buildings carry an “art of living” that has been refined over centuries. The result is a built environment where one can sense dynastic ambition in a grand mosque, spiritual devotion in a humble fountain, and cultural exchange in every horseshoe arch and verdant courtyard. As Morocco moves forward, this inheritance ensures that new expressions will continue to root themselves in a profound legacy; keeping the dialogue between tradition and innovation very much alive.

References:

Abu-Lughod, Janet. Rabats: Urban Apartheid in Morocco. Princeton University Press, 1980.

Barrucand, Marianne, and Achim Bednorz. Moorish Architecture in Andalusia. Taschen, 1992.

Bloom, Jonathan M. Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700–1800. Yale University Press, 2020.

Deverdun, Gaston. Marrakech: Des origines à 1912. Éditions Techniques Nord-Africaines, 1959.

Doris Leslie Blau. A Comprehensive Guide to Tribal Moroccan Rugs. Doris Leslie Blau Blog, 2023.

Lemineur, Tamy. Hassan II Mosque: Architectural Jewel Open to the Sea and Sky. Atalayar, 15 Apr. 2024.

Métalsi, Mohamed. Fès: La Ville Essentielle. ACR Édition, 2003.

Torti, Abdelaziz, et al. Le Maroc andalou: à la découverte d’un art de vivre. Ministère de la Culture (Morocco) & Museum With No Frontiers, 2010.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Medina of Fez and Ksar of Ait-Ben-Haddou. whc.unesco.org, UNESCO, accessed 2025.

Wilbaux, Quentin. La médina de Marrakech: Formation des espaces urbains d’une ancienne capitale. L’Harmattan, 2001.