In this second part of our exploration of Turkish art and culture, we delve into a rich array of traditions and creative expressions that have shaped Turkey’s cultural identity. Part One introduced foundational historical and artistic contexts; Part Two continues by examining specific art forms, from the steam-filled architecture of the Ottoman hamam to the lively atmosphere of coffeehouses, the intricate crafts of carpets and pottery, the rhythms of music and dance, the culinary arts, literary inspirations, the swirling patterns of ebru marbling, the shadows of Karagöz puppetry, the evolution of modern art amid Western influence, and the creative contributions of the Turkish diaspora.

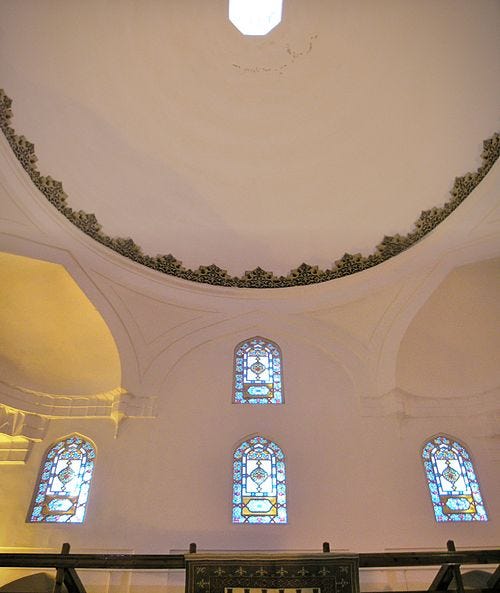

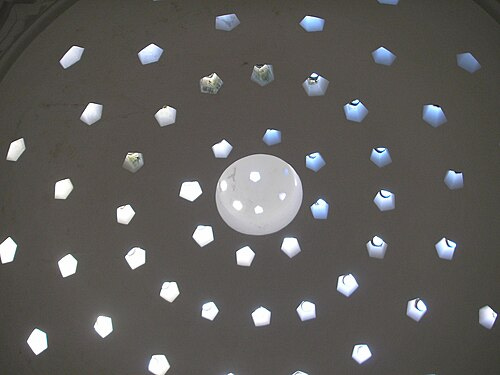

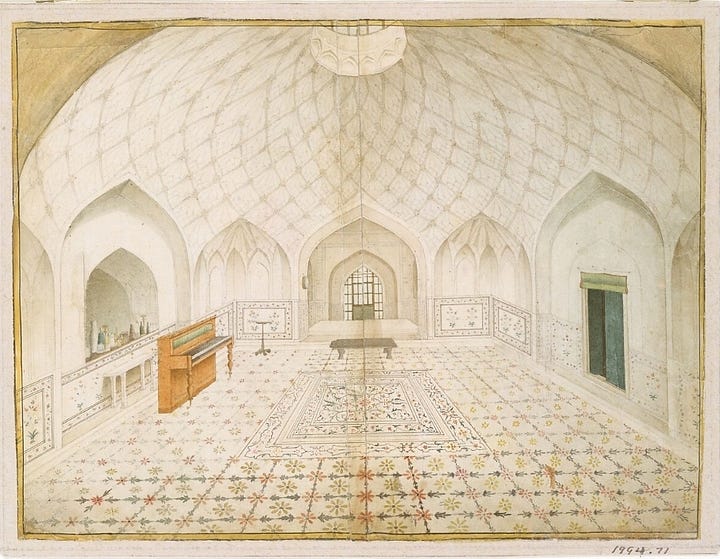

The Turkish bath (hamam) is as much a work of art and architecture as it is a space for bathing and socializing. Ottoman-era hamams are considered architectural masterpieces, evolving from earlier Roman and Byzantine bathhouse designs to create their own distinct style. A typical hamam features a progression of specialized chambers (cool, warm, and hot rooms) centered around a main hot room crowned with a dome. These domed ceilings are not only engineering feats but artistic elements: often pierced with small star or round openings that sprinkle soft light into the steam, an effect both functional and beautiful. Interior surfaces gleam with marble, including the large heated göbek taşı (central marble platform) where bathers receive scrubs and massages. Historical hamams ingeniously used an underfloor heating system (hypocaust) and channels to circulate hot air and water, showcasing the Ottomans’ technical innovation in service of comfort.

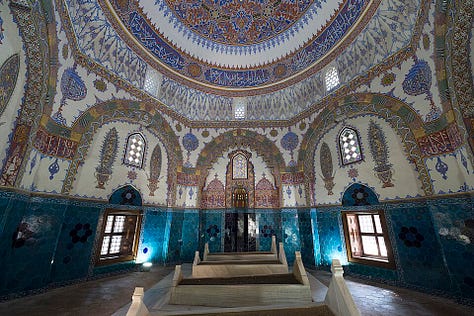

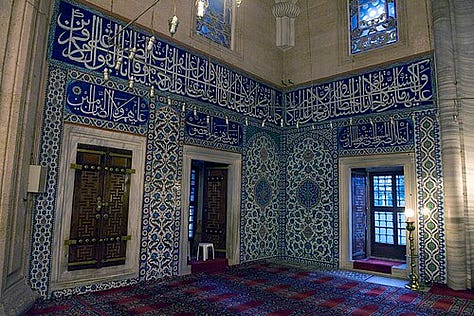

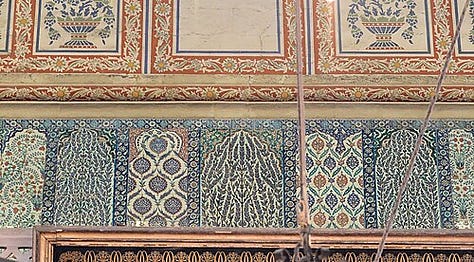

Ottoman hamam architecture balances practicality with artistic expression. The finest examples, many designed by the great Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, achieve a grand scale and elegant symmetry while fulfilling their hygienic and social functions. For example, the 16th-century Hürrem Sultan Hamam in Istanbul (designed by Sinan) and the 18th-century Cağaloğlu Hamam (with its later Baroque details) stand as living monuments to this blend of art and engineering. The design of these baths reflects a cultural fusion: Islamic aesthetics (geometric patterns, calligraphic or floral tile work) combine with inherited Byzantine layouts (central domed halls with adjoining smaller rooms) and even traces of Central Asian elements (like the raised platform). Many hamams were embellished with decorative tile panels, carved stone reliefs, and calligraphic inscriptions, adding visual artistry to the cleansing ritual. The overall effect was a serene, otherworldly space where light, steam, and ornate design combined to elevate the act of bathing into an artistic and almost spiritual experience.

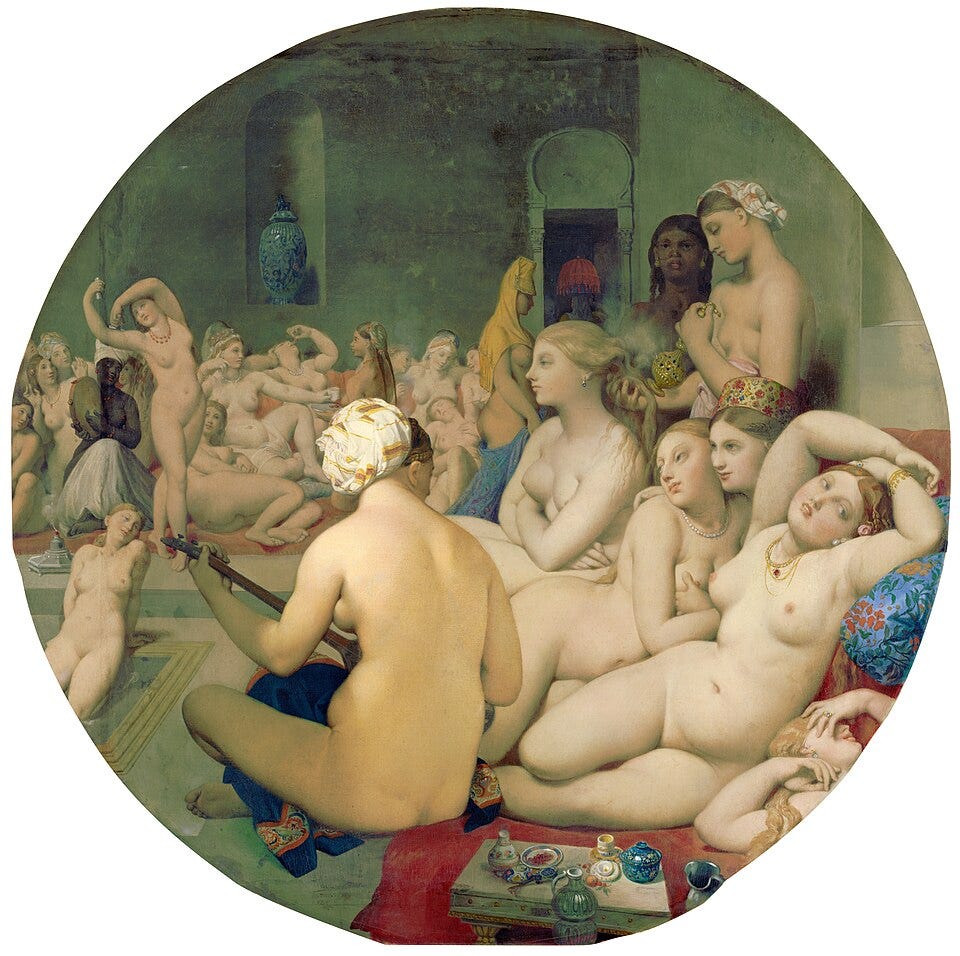

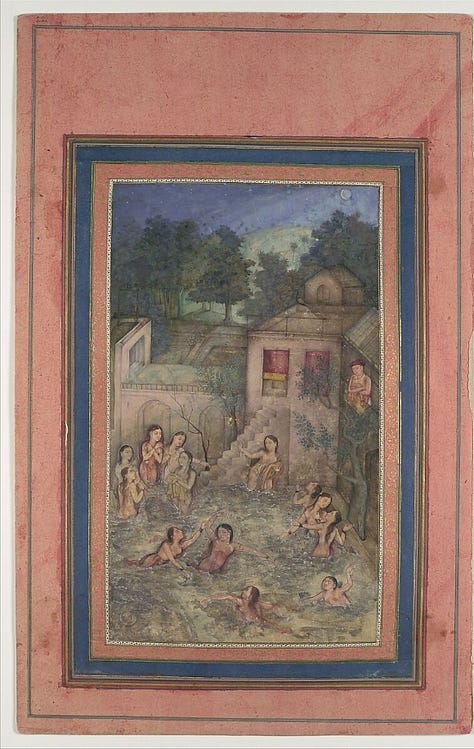

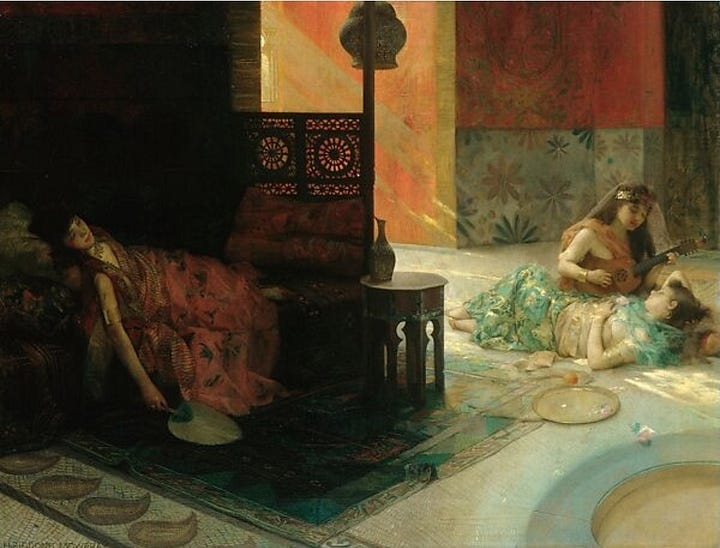

Beyond architecture, hamams played a significant social and cultural role. As public baths segregated by gender, they provided important communal gathering spaces in Ottoman cities. Women, in particular, treated the hamam as a social venue where music, henna painting, and sharing of food might accompany bathing, while men’s baths were hubs of business and conversation. This sociability, set against the backdrop of marble fountains and domes, inspired art and literature over the centuries. Orientalist painters of the 19th century, for instance, were captivated by hamam scenes, although their portrayals often exoticized the baths, they underscore how hamam architecture and ambiance were seen as quintessentially “Turkish” and visually enchanting. Turkish baths represent an intersection of art, architecture, and daily life. Their enduring design, grand yet human-scaled, utilitarian yet beautiful, embodies the Ottoman talent for integrating artistic elegance into public architecture. Today, restored historic hamams in Istanbul and other cities continue to function, allowing visitors to literally immerse themselves in this living art form and experience the hamam’s mosaic of warm marble, steam, light, and social warmth just as patrons did centuries ago.

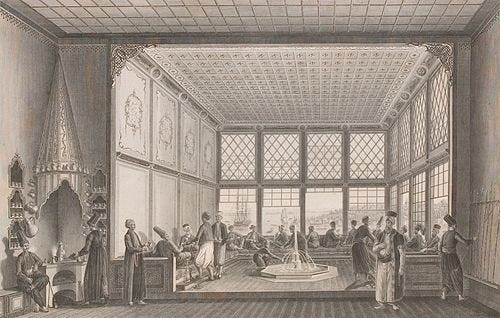

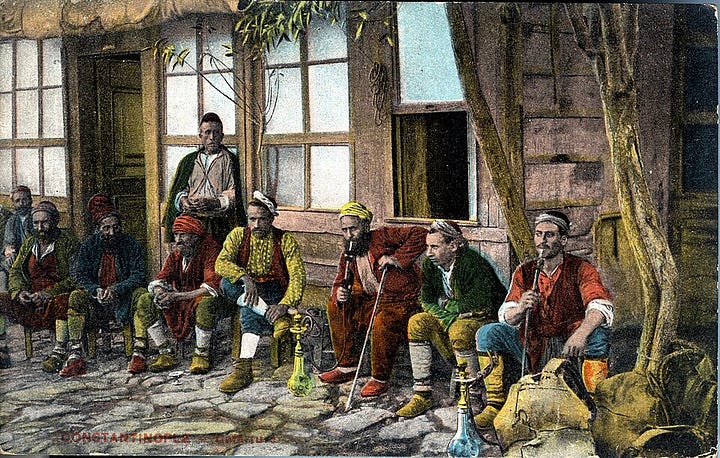

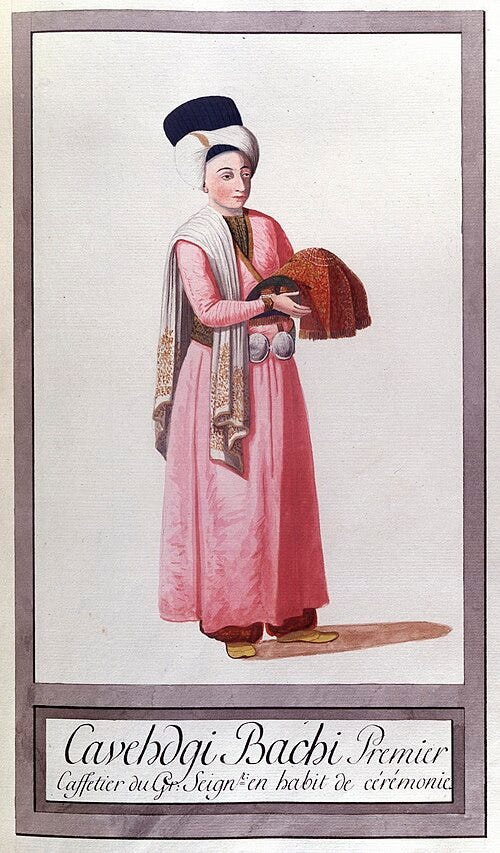

The Turkish coffeehouse (kahvehane) is a storied institution where social ritual meets artistic expression. Since the first coffeehouse opened in Istanbul in 1555 during Suleiman the Magnificent’s reign, these venues have been hubs of conversation, creativity, and community. In the Ottoman era, coffeehouses drew men from all walks of life, from poets and intellectuals to merchants and laborers, into a common space where the simple act of drinking richly brewed Turkish coffee blossomed into a cultural phenomenon. Patrons would linger for hours, engaging in lively debates, listening to stories, and enjoying various entertainments. Indeed, Ottoman coffeehouses became crucibles of art and literature: poets recited verses, meddah (storytellers) performed tales, and people discussed the latest works of history or poetry. The very popularity of these coffeehouses in the 16th–17th centuries coincided with a flowering of Ottoman Divan literature, suggesting a symbiosis between caffeine-fueled sociability and creative output. As one cultural historian notes, coffeehouses functioned as informal “schools of the wise,” democratizing knowledge by allowing even those who were not formally educated to learn from storytellers and literati in a convivial setting.

Beyond verbal arts, coffeehouses nurtured performing arts unique to Turkish culture. Shadow theater found an enthusiastic audience in these establishments. In fact, Karagöz and Hacivat, the famed Turkish shadow puppets, became one of the most iconic art forms to emerge from the coffeehouse scene. In the evenings, especially during the holy month of Ramadan, coffeehouse patrons would gather to watch the Karagöz plays: comedic improvised shadow performances in which the coarse, witty Karagöz and his genteel foil Hacivat lampooned society’s foibles. Through humor and satire, these puppets could criticize politicians or poke fun at social norms, all under the cover of entertainment. The coffeehouse setting was integral to this art, the laughter and interaction of a live café audience spurred the puppeteer’s improvisations. Likewise, meddah storytelling reached an artful height in coffeehouses, where a talented meddah with just a walking stick and handkerchief would mimic multiple characters and captivate listeners with epic romances, folk tales, or witty anecdotes. The immersive atmosphere of the coffeehouse, with its curling coffee smoke and intimate crowd, amplified these oral art forms, turning an evening out into a cultural performance.

Turkish coffee itself was, and remains, an artful tradition. Prepared by boiling finely ground coffee in a cezve (a long-handled pot), often with sugar, it is served in small cups where it develops a distinguishing froth. As recognized by UNESCO, the Turkish coffee tradition is a “symbol of hospitality, friendship, refinement and entertainment”, usually enjoyed in coffeehouses where people meet to converse, share news, and even read books. The act of fortune-telling from coffee grounds left in the cup (a practice known as fal) is itself a creative folk art frequently practiced in these social spaces. In literature and song, Turkish coffee is celebrated as inseparable from the pleasures of conversation and intellectual exchange. It is telling that the Turkish language has a saying, “A cup of coffee commits one to forty years of friendship,” underscoring coffee’s role in cementing social bonds.

The ambience of an old Istanbul coffeehouse was richly artistic: adorned with ornate textiles, low wooden tables, and perhaps hanging brazier lamps, it provided a stage where life and art intermingled. European travelers in the 17th–19th centuries often remarked on the sight of these establishments filled with men engrossed in chess or backgammon, listening to music or simply debating politics over coffee. Such scenes even entered Western art and literature, as the “Oriental coffeehouse” became a motif symbolizing Middle Eastern sociability. Internally, the Ottoman state at times grew wary of coffeehouses for exactly this vibrancy, they were arenas of free thought where political satire and dissent could brew alongside coffee. Sultans like Murad IV temporarily banned coffeehouses due to the political discussions and criticism that percolated within, showing how influential these gatherings had become. Despite crackdowns, the coffeehouses endured as vital public forums.

In modern Turkey, coffeehouses (and their contemporary descendants, cafés) continue to be cherished cultural spaces, though now welcoming to all genders and often more focused on tea as much as coffee. Traditional Turkish coffee culture was inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Heritage list in 2013, affirming its importance not only as a method of brewing but as a communal cultural experience. Even as people’s lifestyles change, the echoes of the classic coffeehouse linger in Turkey’s thriving café scene, literary salons, and even its politics; the term kahvehane still implies a place of spirited talk and community. The art and culture of Turkish coffeehouses exemplify how a daily ritual can blossom into a multifaceted cultural institution. With each tiny cup of strong coffee, they served up a blend of hospitality, intellectual exchange, artistic performance, and social critique – a recipe that deeply flavored Turkish urban life for centuries.

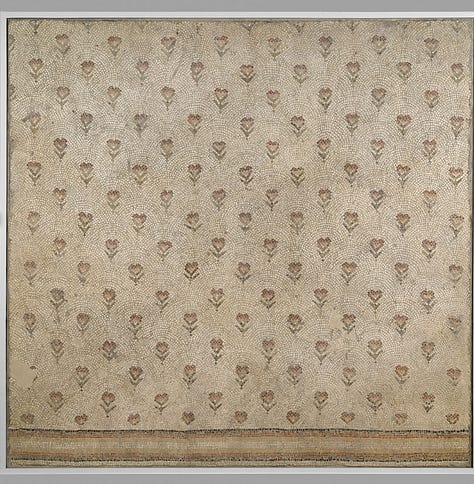

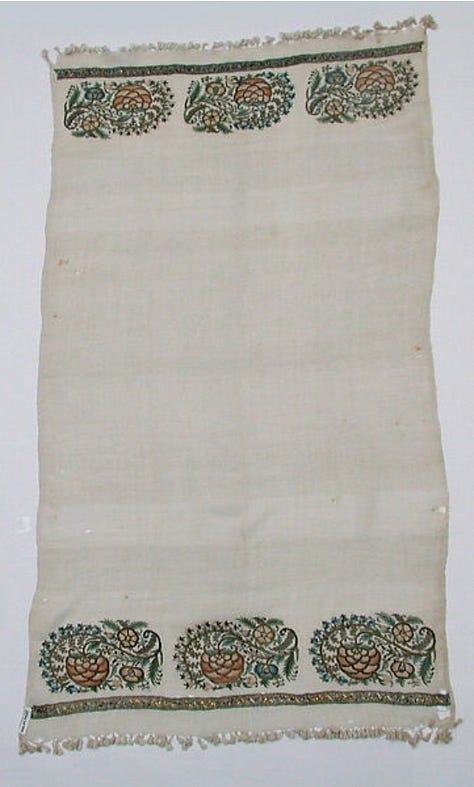

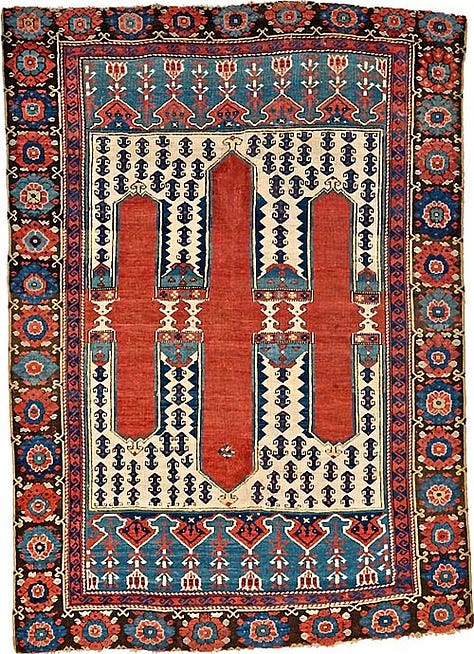

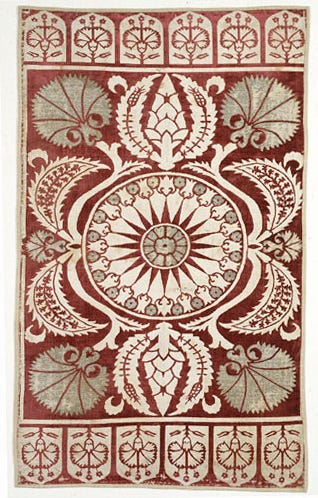

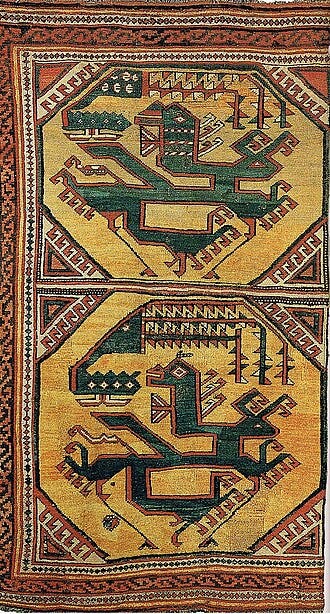

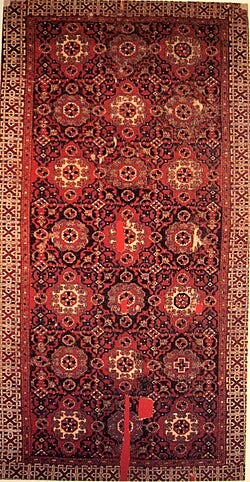

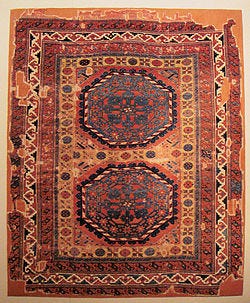

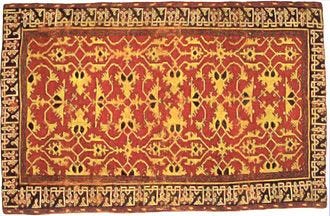

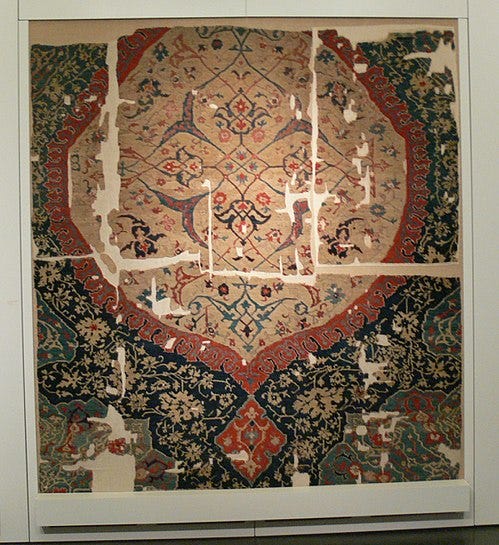

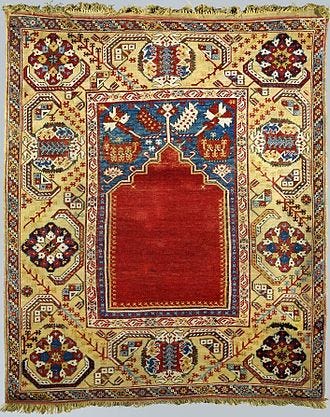

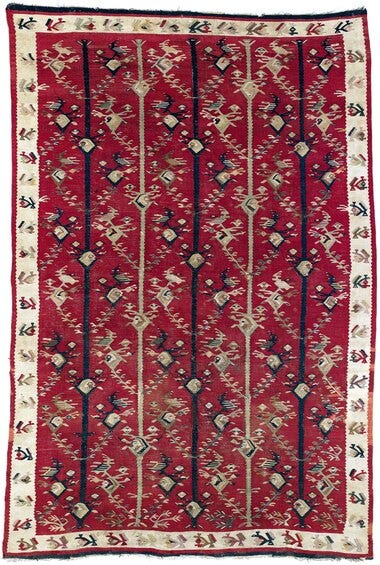

Turkey’s vibrant folk art traditions find exquisite expression in its textiles and ceramics, particularly in handwoven kilims and carpets and in its rich pottery and tile work. These art forms are not only visually stunning crafts but also carriers of cultural identity, with techniques and motifs passed down through generations. Kilim weaving and pile carpet knotting have been practiced in Anatolia for many centuries; archaeological evidence even suggests flat-woven textiles in Anatolia as far back as the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük (7th millennium BCE), and the famous Pazırık carpet (5th century BCE) attests to ancient steppe weaving skills that predate the Turks’ arrival. By the time Turkish tribes settled in Anatolia, they brought Central Asian weaving heritage that merged with local traditions, giving rise to what we recognize as Turkish carpets. UNESCO has recognized the significance of this heritage: in 2010, Traditional Turkish Carpet Weaving was inscribed on the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This was a milestone acknowledging that Anatolian carpet weaving, from intricate silk court rugs to humble nomadic kilims, is a living tradition requiring preservation. Weaving is often a community endeavor, historically done by women, and patterns are learned through apprenticeship within families. Thus, every handwoven rug is more than a utilitarian or decorative object: it is a tapestry of tradition, interlacing the heritage, beliefs, and stories of the weaver’s culture.

Kilims, the flat tapestry-woven rugs, are especially noted for their bold geometric designs and symbolic motifs. Woven traditionally by village and nomadic women, kilims served as household items (rugs, blankets, storage bags) and as part of a young woman’s dowry, imbued with personal meaning. The motifs on Turkish kilims carry rich folklore significance. Common symbols include the elibelinde (“hands on hips”) motif representing the mother goddess or fertility, various talismanic shapes to ward off the evil eye, and stylized plants and animals conveying hopes and prayers. For instance, patterns often function as good luck charms or blessings: a repeating knot or hook motif might protect against misfortune, a stylized ram’s horn symbolizes masculinity and heroism, a fertility motif merges female and male symbols wishing for children, and the ubiquitous eye motif explicitly guards against the evil eye. As one source notes, “symbolism on kilim rugs often pertains to good luck, fertility, longevity in marriage, and protection against the evil eye”. In this way, the weaver literally weaves her aspirations and worldview into the fabric. The colors, too, are natural and locally sourced (wool dyed with madder root red, indigo blue, etc.), giving kilims an earthy authenticity. Many 19th-century European travelers collected Anatolian kilims, admiring their abstract beauty long before abstract art was a concept; today, antique kilims hang in museums as works of art in their own right. Yet in Turkish homes, a kilim on the floor or wall is still a familiar sight; a testament to how this folk art remains integral to daily life and identity. As one modern Turkish saying goes, “Every carpet is a letter from the weaver,” indicating that to those who can read the motifs, a woven rug narrates the joys and sorrows of its maker.

Complementing its textile arts, Turkey is renowned for its pottery and ceramics, which range from rustic everyday ware to the finest glazed tiles that once dazzled on Ottoman palace walls. In Anatolia, pottery-making is an ancient craft dating back to at least 2000 BCE during the Hittite period. One of the cradles of this tradition is Avanos, a town in Cappadocia by the Red River famous for its red clay. There, pottery has been a family trade passed from father to son (and now to daughters as well) for countless generations. Locals proudly recount that Hittite potters first molded this clay three thousand years ago, and that the craft persisted through Greco-Roman times, the Seljuk era, and into the Ottoman period. Visiting an Avanos workshop today, one can see potters shaping clay on foot-powered wheels in the same manner depicted on ancient Hittite artifacts. The continuity is palpable: when an Avanos master potter forms a graceful ewer or a robust cooking pot, he is participating in a chain of knowledge as old as civilization in Anatolia.

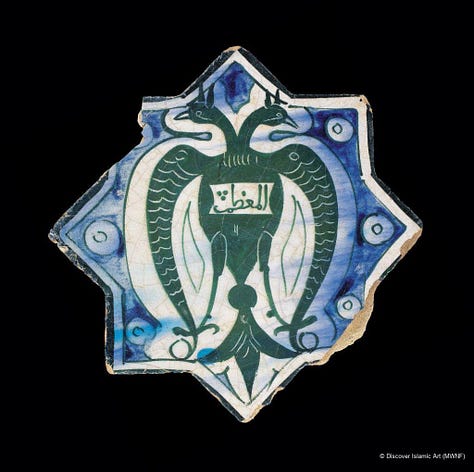

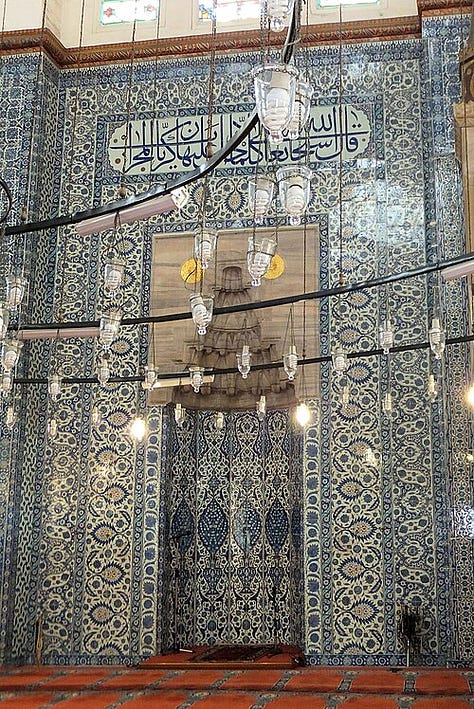

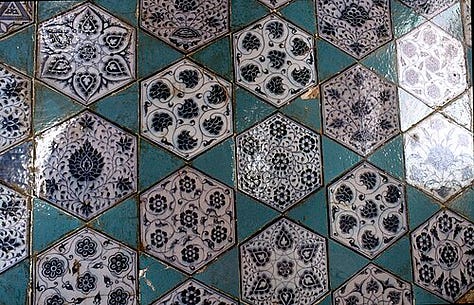

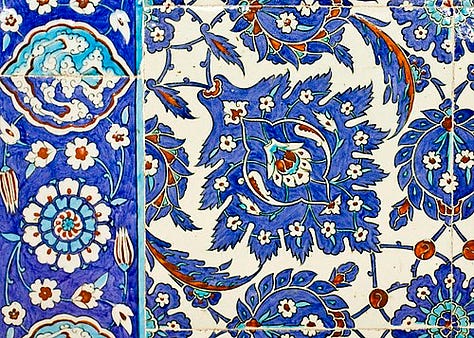

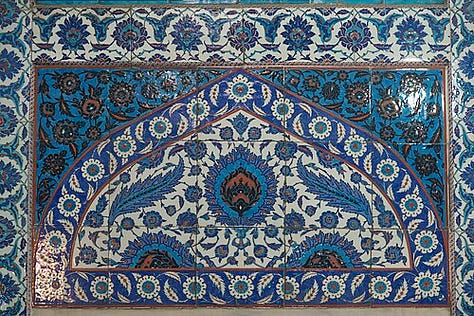

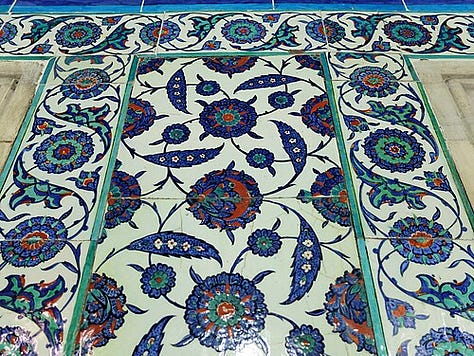

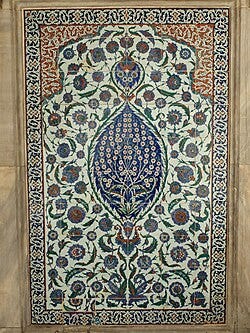

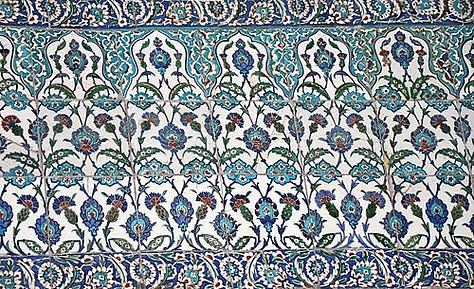

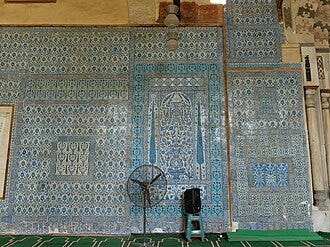

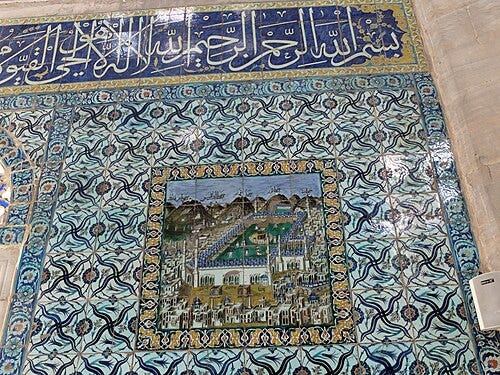

At the pinnacle of Turkish ceramic art are the Ottoman tiles and faience of the 15th–17th centuries, most famously those of İznik and Kütahya. These were not exactly “folk” art, they were produced in workshops patronized by the sultans, but they drew on the collective skill and motifs of Anatolian artisans, elevating them to world-class artistry. İznik pottery developed under the early Ottomans when local potters, inspired by Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, innovated a quartz-infused fritware and perfected brilliant underglaze painting. By the 16th century, İznik tiles displayed a distinctive palette of cobalt blue, turquoise, emerald green, and a striking tomato red, depicting a visual repertoire that combined Ottoman sensibilities with influences from Persian and Chinese art. The designs included rhythmic botanical motifs – graceful tulips, carnations, roses, and saz leaves – often arranged in symmetrical patterns. These tiles were used to breathtaking effect in mosques and palaces; for example, the interior of the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Istanbul (1563) is a veritable gallery of İznik tile art, often described as “a catalogue of designs” emerging from the imperial atelier. In addition to tiles, Ottoman potters made exquisite plates, bowls, and vases that were coveted in Europe and the Middle East. Kütahya, another center, became known for its own style of polychrome ceramics, especially in the 18th century.

On the level of folk craft, Turkish pottery and ceramic design have remained vibrant. Traditional motifs persist; artisans commonly decorate plates or jugs with stylized tulips, vines, bird figures, and abstract patterns that echo those found in tiles or textiles. A signature aesthetic in Turkish popular ceramics is the use of a white background with vivid blue or multicolor designs, a legacy of the İznik style, often outlined in black for definition. These designs are not arbitrary; they tend to reflect regional heritage and symbolism. For instance, a ceramic bowl from Cappadocia might feature motifs of local plants or the evil eye for protection, while contemporary İznik-style pieces replicate classic Ottoman patterns as an homage. Today, visitors to towns like Avanos or Kütahya can watch potters hand-painting these motifs with fine brushes, demonstrating that the craftsmanship and artistry of Turkish ceramics remain highly valued. In many workshops, one finds an interesting blend of old and new: a master might form a shape on a millennia-old style kick-wheel, then fire it in a modern kiln, and finally adorn it with designs drawn from a 16th-century palace scroll or a 21st-century inspiration.

Together, Turkish carpets, kilims, and pottery form a core of the nation’s folk art legacy. They are arts of everyday life, spread on floors, hung on walls, used for dining and storage, yet they carry profound cultural meaning. They also represent a shared regional heritage; similar weaving or pottery traditions exist across Central Asia and the Middle East, and Turkey’s artisans have both influenced and been influenced by those of neighboring cultures through trade along the Silk Road. The enduring popularity of “Turkish rugs” and “Iznik tiles” around the world speaks to their aesthetic appeal. But for the Turkish people, these items are not mere commodities; they symbolize continuity with the past. An Anatolian proverb says, “The carpet is the soul of the home.” Likewise, the Turkish ceramic arts are often referred to as çini sanatı (tile art), emphasizing their connection to art history and identity. With UNESCO and other organizations supporting the preservation of weaving and pottery techniques, Turkey is actively safeguarding these traditions. In villages today, one can still witness communal carpet weaving sessions or potters’ festivals that celebrate these crafts. The art of Turkish kilims, carpets, and pottery, therefore, is truly a living art; continually adapting and yet richly preserving the motifs, skills, and soul of the Turkish folk imagination.

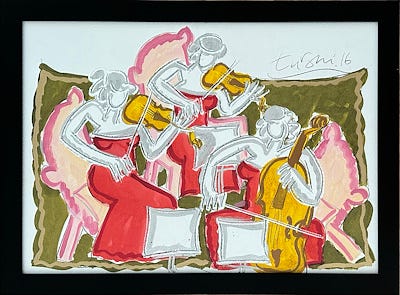

Music and dance are central pillars of Turkey’s cultural arts, encompassing a diverse spectrum from the refined melodies of Ottoman court music to the energetic folk dances of Anatolian villages and the spiritually infused whirling of Sufi dervishes. Turkish music is often described as a bridge between East and West, combining Middle Eastern modes and instruments with influences from Central Asia and, in modern times, Western genres. It can be broadly categorized into Ottoman classical music, folk music, and the music of various ethnic and religious communities (such as Armenian, Greek, Kurdish, or Alevi traditions), each with its own rich repertoire. Correspondingly, dance in Turkey ranges from the choreographed folk dances that vary by region to the sacred dances of Sufi orders and the stylized performances of urban theaters. Together, Turkish music and dance forms a dynamic art realm where rhythm, melody, movement, and storytelling intermingle.

In the realm of classical music, the Ottomans developed an sophisticated art music tradition (Turk Sanat Müziği) characterized by the makam system, complex modes or scales, and a variety of poetic forms. Performed in the courts of sultans and pashas, this music featured instruments like the oud (lute), ney (reed flute), kemençe (bowed fiddle), kanun (zither), and tanbur (long-necked lute), often accompanied by vocals. Composers such as Dede Efendi in the 18th/19th century wrote enduring pieces that are still performed. The lyrics of classical songs were often drawn from Ottoman divan poetry, meaning literature directly influenced the music; songs would be set to ghazals (lyric poems) by famed poets, thus bringing literary art into musical form. The visual arts also intersected with this music; calligraphic art, for example, sometimes transcribed musical compositions or the names of makams in beautiful scripts as a form of homage. Moreover, miniatures from the Ottoman era depict musical gatherings and instruments, showing a historical record of performance practice.

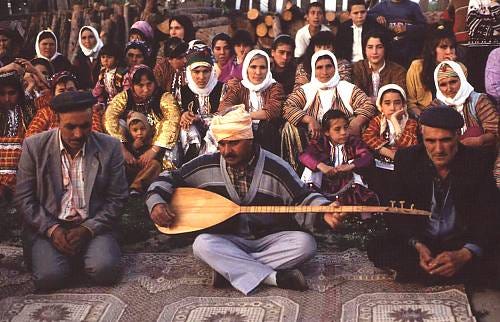

Turkey’s folk music, by contrast, is the music of the people (halk müziği), deeply tied to the rural life of Anatolia. It is usually centered on the storytelling songs of the aşık (bard or troubadour) accompanied by the bağlama (long-necked lute, also called saz). These wandering poet-musicians have been a fixture of Turkish folk culture for centuries; the legend of Aşık Veysel, a blind bard of the 20th century, exemplifies their role as carriers of oral tradition and social commentary. The Aşıklık (minstrelsy) tradition, with its traveling musician-poets, is so vital that it too has been recognized by UNESCO as part of humanity’s intangible heritage. The songs (türkü) they sing recount everything from epic romance and heroism to daily village life, often with improvisational wit and regional dialect. Aşık performances were historically featured at village weddings, fairs, and yes, in coffeehouses as well, where locals would gather to listen to the verses and perhaps dance if the rhythm invited it.

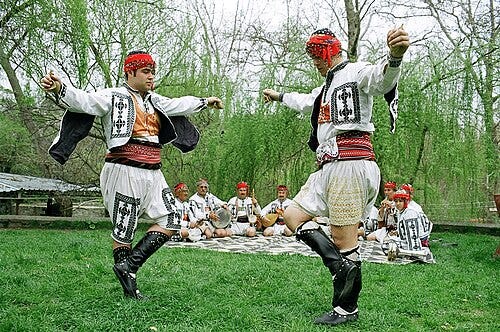

Speaking of dance, Turkey’s folk dances are as varied as its landscape. Every region has its hallmark dance; the hora and karşılama in Thrace, the zeybek in the Aegean (where lone male dancers emulate bold eagle-like movements), the halay in Central and Eastern Anatolia (a joyous line dance with people linked arm-in-arm), the horon in the Black Sea (a fast-paced circle dance often to the frenetic sound of the tulum, or bagpipe), and the bar dances of the Northeast. These dances are communal and performed at celebratory events like weddings, harvest festivals, or national holidays. Costumes are integral to the visual spectacle: dancers don brightly colored traditional outfits specific to their region, for example, the zeybek dancers wear short jackets and decorative trousers with a distinctive headgear, while women in Eastern halay groups might wear sequined dresses and flowing scarves. The choreography often reflects everyday actions or symbolic movements: in some halay dances, slow and deliberate steps followed by sudden kicks might represent sowing and reaping in agriculture, whereas in Black Sea horon, the rapid shuffling footwork mirrors the choppy sea waves.

One of the most internationally renowned Turkish dance forms is the whirling dervish ceremony, known as the Mevlevi Sema. This is not a dance in the entertainment sense, but a sacred Sufi ritual performed by the Mevlevi order (followers of the poet-philosopher Mevlâna Jalaluddin Rumi). The Mevlevi Sema was proclaimed a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2005. In this ceremony, dervishes in flowing white gowns and tall brown felt hats rotate in unison on their left foot with their arms extended, one hand up to receive divine grace, the other turned down to earth. Accompanied by plaintive flute (ney) music, chanting, and the steady rhythm of a drum, the dervishes whirl themselves into a meditative trance, symbolizing the soul’s mystical journey towards God. The visual of this dance is mesmerizing: the skirts of the dervishes billow out like white lotus blossoms as they spin, creating an ethereal image that has inspired many a painter and photographer. The Sema ceremony, originating in Konya in the 13th century, is rooted in Rumi’s spiritual teachings and remains a powerful example of dance as a form of worship. Each December, commemorative ceremonies in Konya draw visitors from around the world to witness this moving art. Described by UNESCO as “the whirling dervishes’ spiritual Sufi dance, rooted in Mevlâna Rumi’s teachings, [which] symbolizes a connection with the divine”, the Sema transcends mere performance, offering participants and viewers alike a glimpse of the sublime through art.

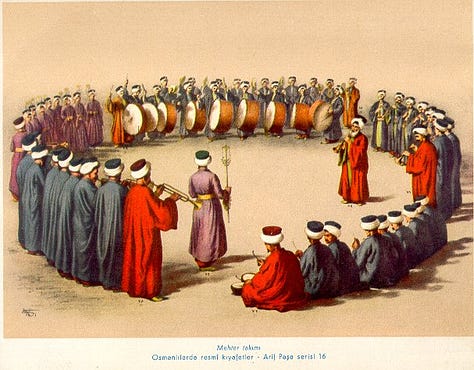

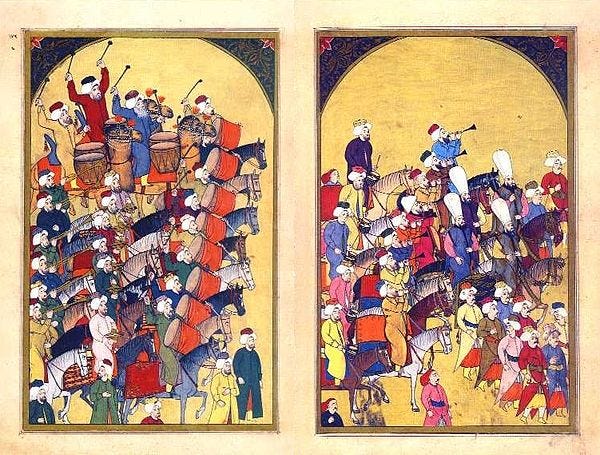

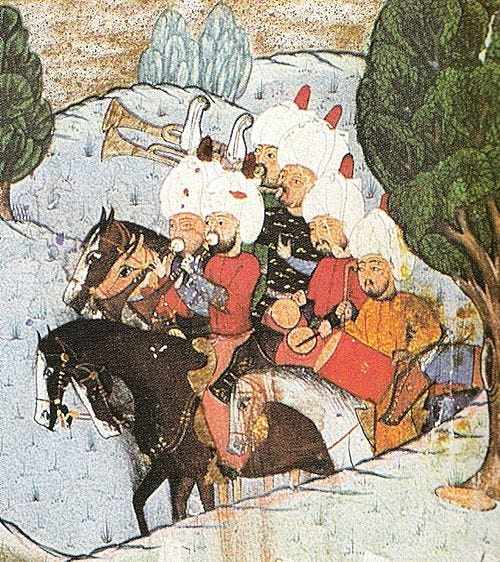

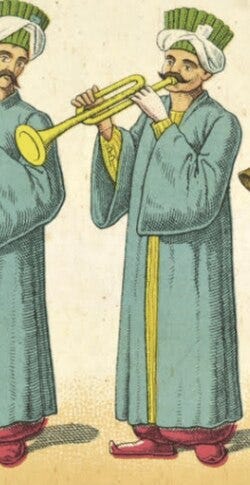

In addition to these traditional forms, Janissary music and dance also left a legacy. The Ottoman military band, or Mehter, famed for its crashing cymbals, pounding drums, zurnas (shrill woodwinds), and colorful uniforms, was both a sonic and visual spectacle. The mehteran would march and play martial tunes, and their performances often included rudimentary choreography – standard bearers twirling flags or band members rhythmically swaying. Mehter music had a notable influence on European classical composers (the “Alla Turca” trend, seen in Mozart’s and Beethoven’s works), proving that even martial arts had an artistic exchange. Folk dances sometimes incorporate moves reminiscent of martial training (like men crouching and leaping with swords in some Kılıç Kalkan dances of Bursa, a reenactment of Ottoman soldiers’ sword-and-shield demonstrations).

Modern Turkey continues to celebrate and innovate its musical and dance heritage. On one hand, state ensembles like the Turkish State Folk Dance Ensemble stage polished performances showcasing regional dances in full costume for local and international audiences, ensuring these arts gain recognition and survive in the era of globalization. On the other hand, contemporary musicians blend traditional instruments with Western ones, Turkish folk-rock and pop often incorporate bağlama or ney melodies into modern arrangements, bringing folk tunes to younger listeners in new forms. Turkish classical music still thrives in urban culture through conservatories, radio programs, and live concerts, preserving the centuries-old makam compositions. Meanwhile, there’s also a strong tradition of Turkish ballet and opera dating to the Republican reforms, as well as a burgeoning modern dance scene, but those belong more to Western-style high arts influenced by Europe.

It’s worth noting the role of dance in social and life-cycle events. Folk dances remain a staple of weddings: in rural areas, it’s common to see the entire community join a halay line, from the elderly to children, dancing to the invigorating sound of davul (drum) and zurna (reed pipe) played by local musicians. Certain dances have ceremonial importance, for example, in the Henna Night before a wedding, women might perform specific folk songs and dances to send off the bride. During Nevruz (spring new year) celebrations or Hıdrellez (spring festival) in Turkey, music and dance are communal ways to mark seasonal change, often involving circle dances around bonfires, singing folk songs that have been heard for generations. These events highlight how intimately dance and music are woven into the social fabric.

Turkey’s musical instruments themselves are works of art and tradition. The construction of a saz or ney is a craft passed down among luthiers. In 2023, the craftsmanship and performance of the mey (a double-reed woodwind similar to the Armenian duduk, used in folk music) was jointly inscribed by Azerbaijan and Turkey on UNESCO’s list, recognizing that even making and playing a single instrument constitutes important intangible heritage. The mey’s haunting, mournful tone is often heard at weddings and festivals in Eastern Anatolia, demonstrating how an instrument can encapsulate the soul of a region’s music.

The art of Turkish music and dance is a multifaceted tapestry reflecting the country’s history and diversity. Whether it is the spiritual turning of dervishes, the fiery footwork of a Black Sea horon, the plaintive strings of a bağlama accompanying a bard’s tale, or the polished composition of an Ottoman fasıl ensemble, each performance is imbued with cultural meaning. These arts serve both to entertain and to connect – connecting people to each other in communal joy or devotion, and connecting the present to the past through songs and movements inherited from ancestors. As UNESCO’s recognition of Mevlevi Sema and aşık traditions attests, Turkish music and dance are not static relics but living arts that continue to inspire and unite communities. They remain a vital avenue for artistic expression in Turkey, celebrating the nation’s heritage while continuously evolving with new creative energies.

Turkish cuisine is often described as a culinary arts tradition, a phrase that highlights how cooking in Turkey goes well beyond mere sustenance to become a creative cultural expression. From the elaborate palace feasts of the Ottoman sultans to the home-cooked specialties passed down through families, the food of Turkey reflects aesthetic principles, refined techniques, and a rich tapestry of influences. Indeed, during the zenith of the Ottoman Empire, cooking was regarded as a high art form, palace chefs were akin to artists or virtuoso craftsmen, meticulously developing new dishes and refining old ones. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the imperial kitchens at Topkapı Palace in Istanbul employed hundreds of specialized cooks, each mastering a particular category of dish (soups, pilafs, kebabs, pastries, candies, etc.). These chefs competed and collaborated to create the most exquisite flavors and presentations imaginable, giving birth to what became known as Ottoman palace cuisine. Historical records and travelogues describe lavish banquets with dozens of courses where each dish was a feast for the senses, visually appealing, aromatic with exotic spices, and balanced in taste and texture. To this day, some of those recipes endure (with names like Hünkar Beğendi, “Sultan’s Delight” eggplant puree with lamb, or Mahmudiyye, a delicate chicken stew with almonds and apricots), testifying to the creativity of Ottoman cooks. As one modern commentary on Ottoman culinary history notes, the era of Süleiman the Magnificent and Mehmet II was “a time when cooking was regarded as an art form and eating was a pleasure, a legacy that is at the root of Turkish cooking today”.

The artistry of Turkish cuisine is evident in its variety and presentation. Spanning a vast geography and drawing from ancestral Turkic, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, and Balkan influences, Turkish cooking orchestrates a mosaic of flavors and techniques. Consider the meze table, an array of small dishes akin to edible artwork: creamy haydari yogurt dip swirled with herbs, vibrant red pepper muhammara garnished with walnut, dolma (vine leaves or vegetables stuffed with rice) arranged neatly on a platter, and jewel-like ezme (spicy tomato salsa) sprinkled with parsley. A well-composed meze spread is a culinary canvas, balancing colors, shapes, and tastes; the contrast of a glossy roasted eggplant salad beside a bowl of bright white yogurt with mint, or the textural interplay of a crunchy fried börek next to a silky hummus. Such attention to aesthetic detail reflects the cultural importance of hospitality: to honor guests, one must delight their eyes as well as their palate. Even in humble homes, it’s common to see a simple dish like çoban salatası (shepherd’s salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers) presented beautifully chopped and arranged, glistening with olive oil and flecks of oregano.

At the heart of Turkish cooking is a mastery of techniques that elevates ingredients to their finest expression, culinary craftsmanship honed over centuries. Take, for example, the making of baklava, the famed Turkish pastry. Preparing baklava is akin to sculpting and architecture: paper-thin sheets of phyllo dough (often rolled out so expertly that one could read newspaper text through them) are layered with ground nuts and butter in a large pan, then baked and soaked in syrup to yield a diamond-shaped confection that’s crisp, flaky, and lustrous. The process requires dexterity and precision, and traditionally, master bakers train apprentices for years in this craft. Or consider the art of brewing Turkish tea (çay) in a double-stacked teapot (çaydanlık): achieving the right strength and clarity of the tea is a subtle skill, and pouring it into tulip-shaped glasses without spilling, to just the right level of amber hue, is done with graceful familiarity. These examples underscore that Turkish cuisine values the how of cooking as much as the what.

Furthermore, Turkish cuisine can be seen as an edible history, where each dish tells a story and carries an artistic heritage. Many recipes are very old, preserved not in written form initially but through practice and oral tradition, much like folk music or crafts. For instance, the layered meat and vegetable pie called tüffahiye was recorded in a 15th-century palace cookbook and was essentially a savory “apple pie” stew, such historical recipes inform modern variations. The influence of different cultures is an open secret in Turkish cooking; Persian, Arabic, and Anatolian Seljuk legacies brought early use of rice, sour pomegranate syrup, stuffed vegetables, and spices; the Ottoman court’s cosmopolitan reach introduced new ingredients (like tomatoes, beans, and peppers from the Americas via Europe after the 16th century) and fostered fusion. Yet, these foreign elements were absorbed and transformed in the Ottoman-Turkish kitchen. For example, pilav (pilaf) and dolma (stuffed foods) show Persian roots but became distinctively Turkish in style. The famed yogurt-based dishes (like mantı dumplings doused in garlic yogurt) reflect Central Asian Turkic origins. And sweets like lokum (Turkish delight) or güllaç (a delicate rosewater pudding with thin starch sheets) reveal the Ottoman penchant for turning food into a refined indulgence. Each dish, in a sense, is a piece of art that blends influences, analogous to how Ottoman visual arts blended Persian, European, and indigenous motifs.

Presentation and ceremony elevate Turkish cuisine to art, especially in its role in social customs and celebrations. Food is central to Turkish hospitality; the saying goes, “Misafirin umduğunu değil, bulduğunu yer,” meaning “A guest eats what he finds, not what he hopes,” highlighting the host’s duty to offer abundantly. The arrangement of a Turkish sofra (dining spread) is akin to curating an exhibition: one thinks about the balance of hot and cold dishes, the sequence of courses, and the garnishes that will please the eye. Certain culinary customs are indeed performative arts. Consider the spectacle of the çırağan: in Ottoman times, this was a torchlit banquet by the Bosphorus, famous for its grandeur. Or the continued practice of the Turkish coffee fortune reading: after finishing a cup of Turkish coffee, the drinker inverts the cup on the saucer, allowing the grounds to drip and form patterns on the cup’s interior. A fortune-teller then “reads” these patterns, interpreting symbols and shapes, effectively, this is abstract art created by coffee and interpreted through imaginative storytelling. It’s a small ritual that demonstrates the Turkish knack for infusing daily life with creativity and meaning.

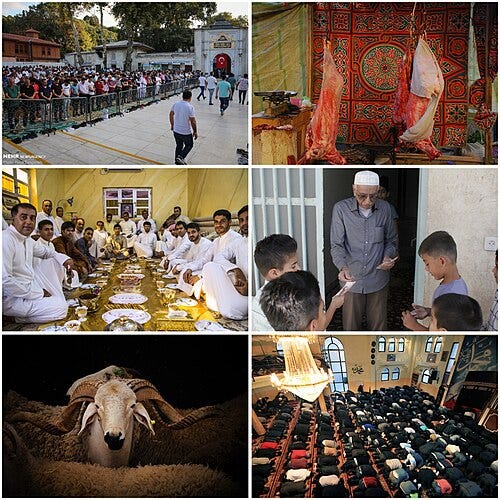

Festive and ceremonial foods also showcase artistry. During Ramadan, the daily fast is broken at iftar with special meals that often start with a date and proceed to soups and an array of dishes, often including recipes made only in this month (like güllaç dessert). Major holidays like Kurban Bayram (Feast of Sacrifice) involve dividing and distributing meat in a mindful, charitable manner, often resulting in communal cooking like large cauldrons of stewed meat and wheat (keşkek). Keşkek, in fact, is a dish so rooted in communal art that in some villages, men and women take turns rhythmically pounding the ingredients in a pot to the beat of drums and zurnas, almost dancing as they cook; this practice was recognized by UNESCO as well. At weddings, it’s tradition in many regions to have specific dishes that symbolize prosperity and unity, and their preparation is a collective act (for example, many Central Anatolian weddings serve yağlama or etli pilav, made by teams of relatives). Even the everyday art of making bread, a staple in Turkey, has deep cultural resonance: techniques for hand-rolling yufka flatbread or baking village bread in clay ovens are taught and practiced with pride, and recently “flatbread making and sharing culture” was jointly inscribed by several countries including Turkey in UNESCO’s heritage list. This underscores that what might seem ordinary, bread, is actually part of an extraordinary cultural continuum and craft.

Modern Turkish gastronomy continues to evolve as an art form, bridging tradition and innovation. Renowned Turkish chefs today often experiment with Ottoman-era recipes, “reinventing” them with contemporary presentations (for instance, serving a deconstructed aşure pudding as a plated gourmet dessert) or fusing Anatolian ingredients with international techniques (like creating sushi with vine leaves and bulgur). Istanbul and Gaziantep are now recognized internationally for their culinary scenes; Gaziantep in particular was named a UNESCO Creative City of Gastronomy, celebrating its rich repertoire of dishes and sweets (especially its legendary pistachio baklava). These developments highlight that Turkish cuisine’s artistic journey is ongoing – chefs are effectively cultural artists who remix the old and new.

In conclusion, Turkish cuisine can rightfully be called an art form because it embodies creativity, tradition, and aesthetic pleasure much like painting or music. The depth of its history and the breadth of its regional variety provide an expansive “palette” of flavors and techniques for cooks to work with. Whether one is savoring a simple simit (sesame bread ring) on an Istanbul street or dining on a many-course Ottoman-style feast, there is a sense that food in Turkey engages more than just appetite; it engages memory, sight, smell, and emotion. As culinary historian Özge Samancı notes, Turkish food culture is an intangible cultural heritage in itself, where recipes are akin to oral literature and cooking methods akin to handicrafts. Thus, preparing and sharing a meal is a kind of performance art that reinforces community bonds and conveys cultural knowledge. It is telling that in Turkish, the word for cooking, yemek yapmak, literally means “to make food”, implying creation, and a good cook is often praised as being ustalıkla (with mastery, like a master artist). The artistry of Turkish cuisine lies in this masterful creation and the joy and meaning it brings to those who partake, fulfilling not just the stomach but the soul.

Turkish literature, with its deep poetic and narrative traditions, has significantly influenced the country’s visual arts over the centuries, creating a rich dialogue between the written word and imagery. This interrelationship can be traced back to the medieval and early modern periods, when the Ottoman court’s love of literature directly inspired paintings and decorative arts, and extends into the modern era, where novels and poems continue to stimulate visual artists in new ways.

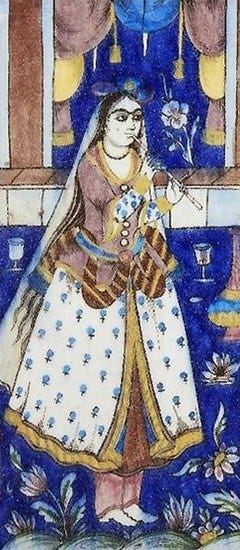

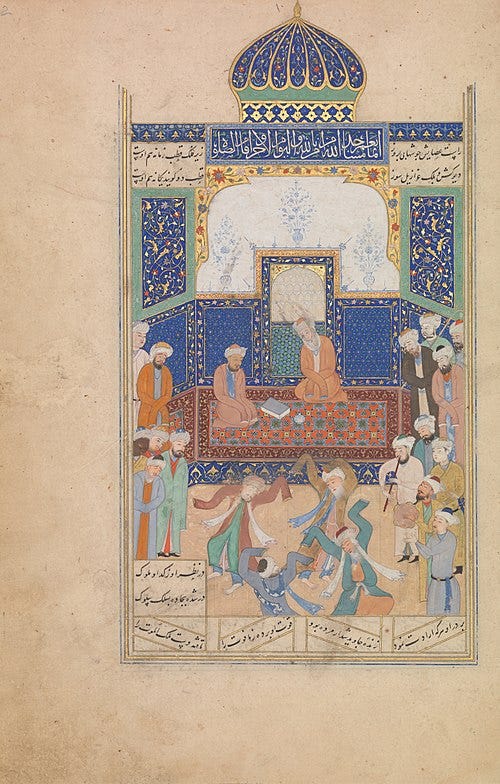

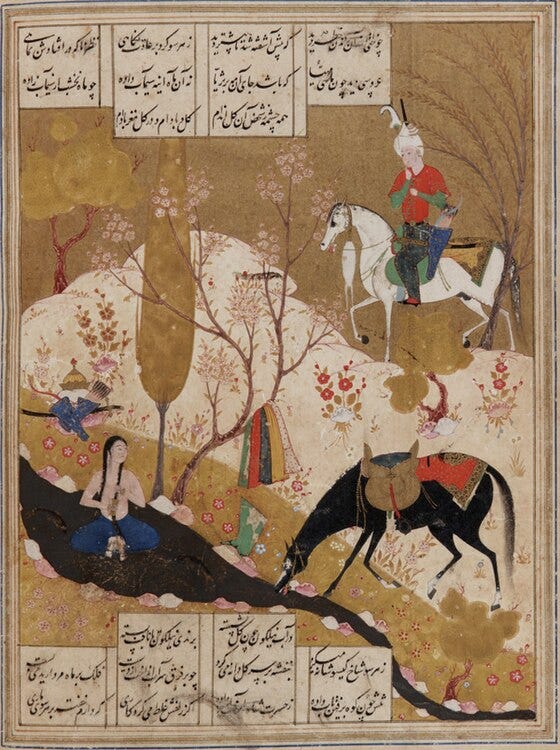

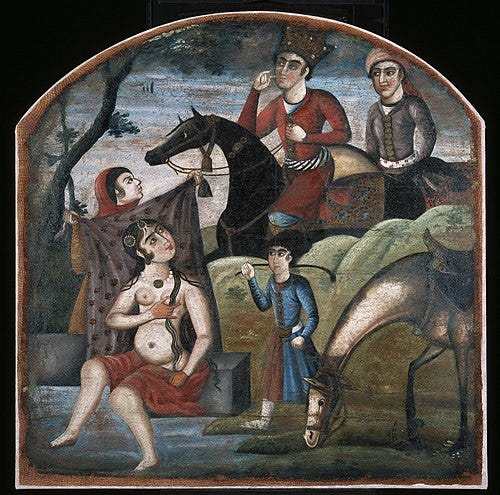

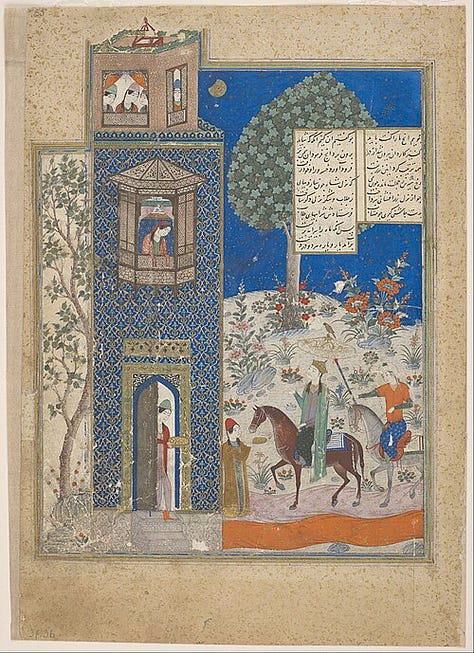

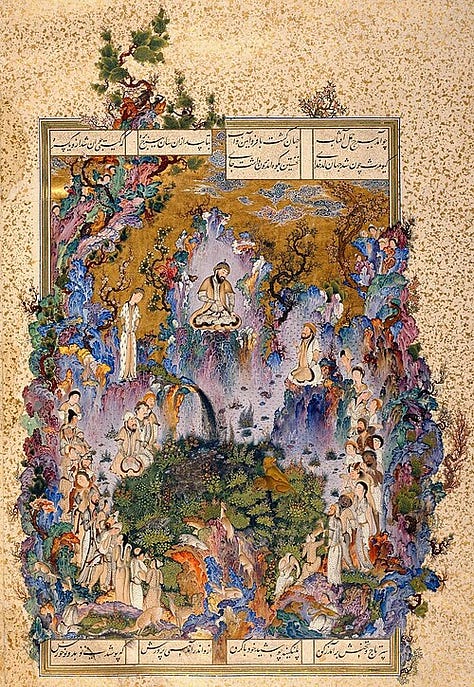

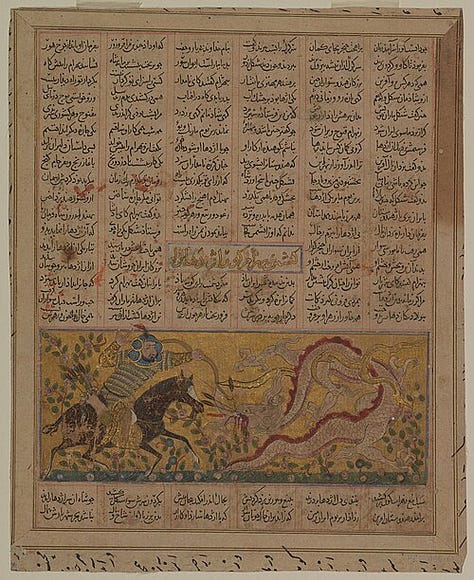

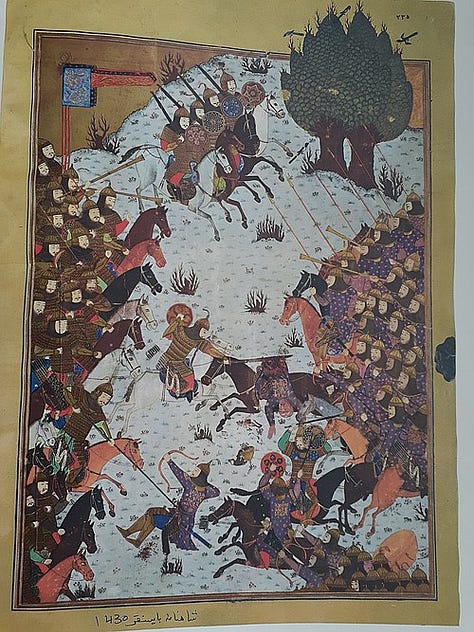

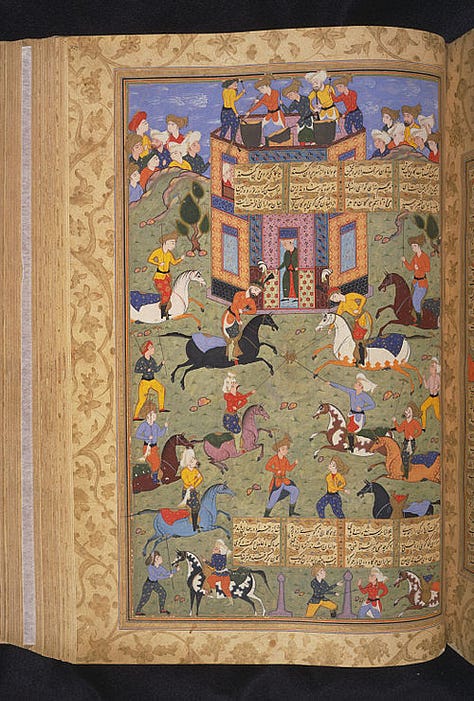

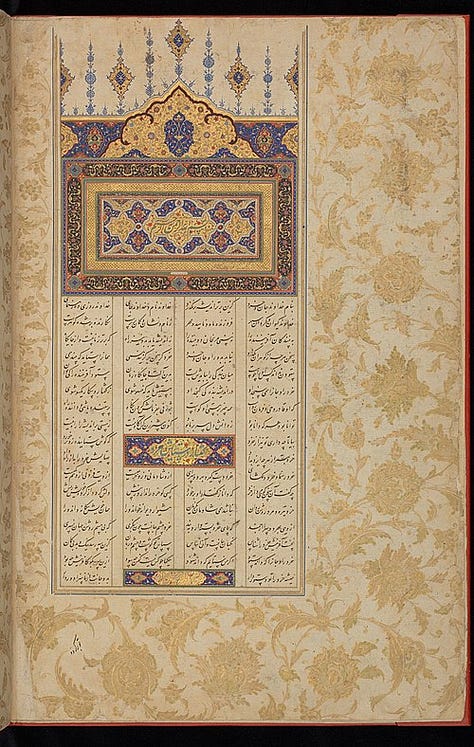

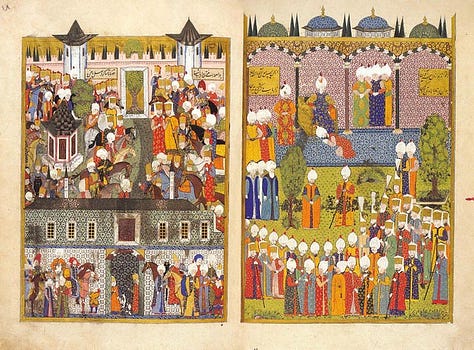

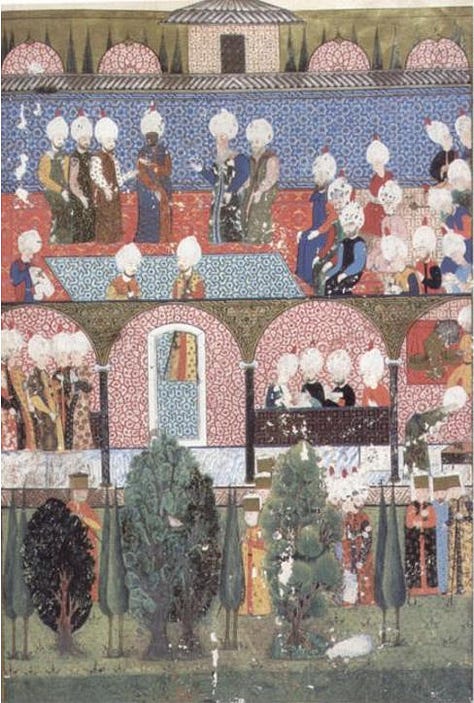

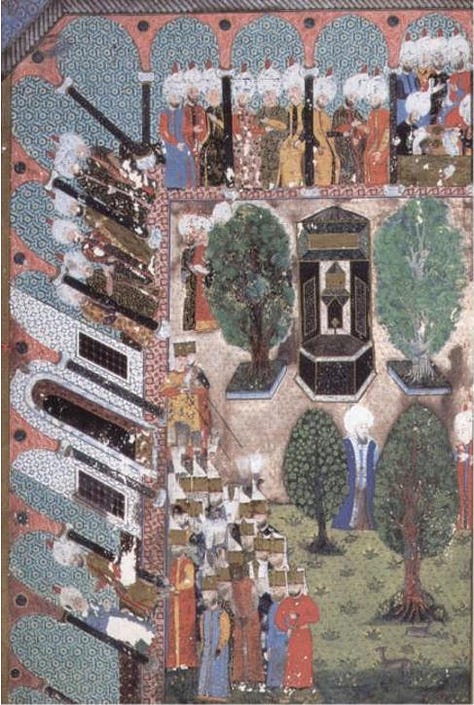

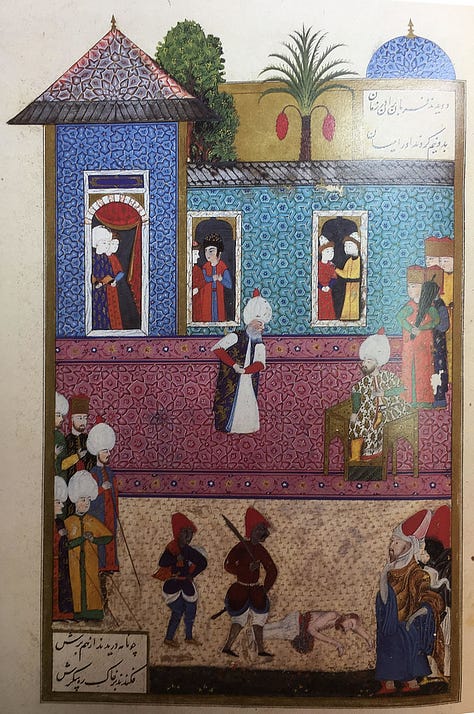

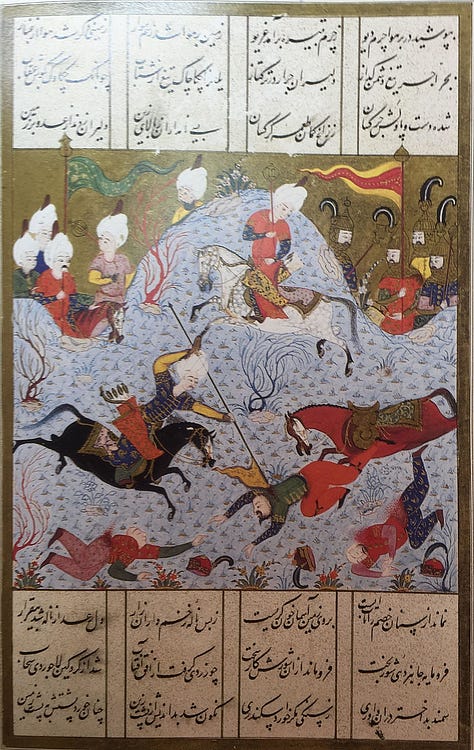

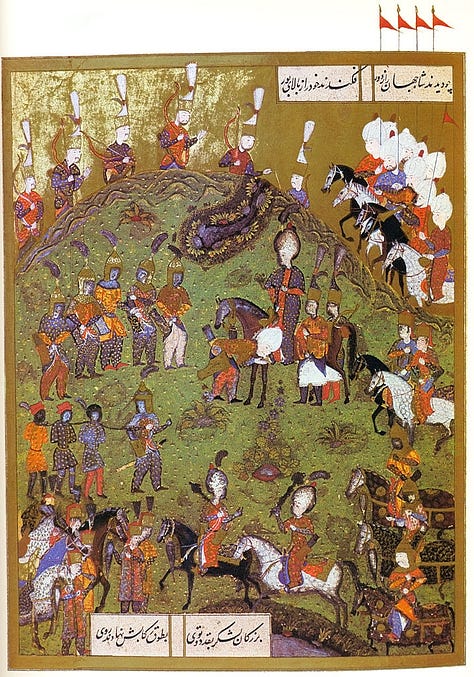

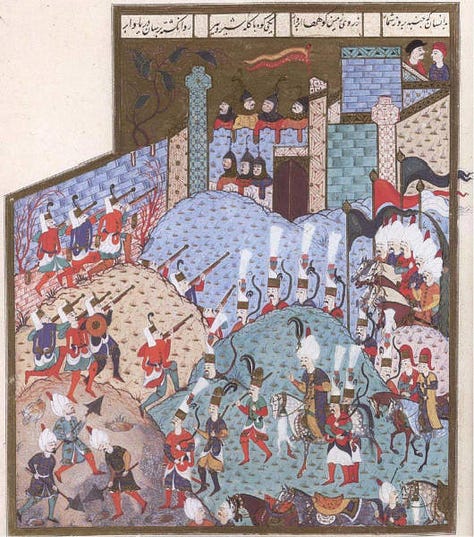

During the Ottoman Empire, one of the clearest intersections of literature and visual art was the art of manuscript illustration. The Ottomans inherited and developed the Islamic tradition of the miniature painting, small-scale, detailed illustrations that accompanied texts, much like illuminated manuscripts in Europe. These miniatures often depicted scenes from literary works, including poetry, epic romances, and historical chronicles. For example, the 16th-century poet Fuzuli’s renowned Turkish rendition of the romance Leyla and Majnun was copied in lavish manuscripts that were illuminated with delicate miniatures of the star-crossed lovers in desert landscapes or secret meetings. Similarly, Ottoman illustrated copies of Persian classics like Nezami’s Khosrow and Shirin or Firdausi’s Shahnama (Book of Kings) were produced, in which Ottoman painters combined Persian stylistic influences with their own perspective to visualize these beloved stories. An important treatise known as the Hünername (Book of Skills) and historical chronicles like the Surname (festival books) were richly illustrated to celebrate the deeds of sultans, blending literary panegyric with visual glorification.

Ottoman miniaturists, often working in the nakkaşhane (palace workshops), thus translated written narratives into visual form, adhering to a narrative language of art that paralleled the text. As art historian Zeren Tanındı explains, there was a longstanding tradition in the Islamic world of creating visual representations for written texts and oral narratives, and the Ottomans embraced and sustained this fully. Ottoman pictorial art “followed the main principles of the narrative language of book illustrations”, meaning that painters focused on clarity of storytelling in images, rather than personal expression. The skills were passed master-to-apprentice, ensuring continuity in style and technique. Each miniature was not meant to stand alone as an easel painting might, but to complement and illuminate a piece of literature. For example, an illustrated history of Sultan Süleyman’s campaigns would include miniatures of key battles described in the text, effectively bringing the text to life visually. In this way, literature directly guided the content of visual art.

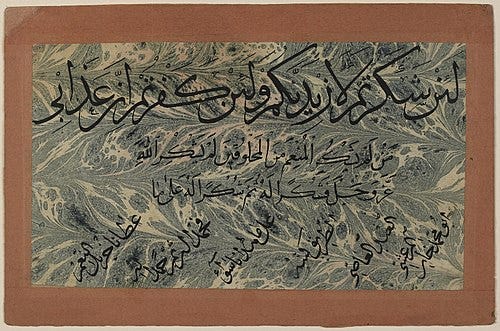

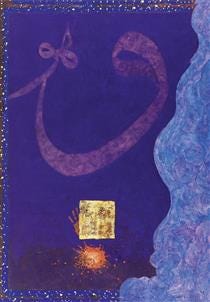

In addition to narrative painting, Islamic calligraphy in Ottoman lands was another visual art form deeply influenced by literature, or more precisely, by the literary and sacred nature of its texts. Calligraphy was regarded as the highest of arts in Islamic culture, and Ottoman calligraphers turned Qur’anic verses, hadiths, and lines of poetry into visual masterpieces of flowing script. The content of these calligraphic panels was often literary or poetic. Notably, many calligraphic compositions featured lines of mystical poetry by figures like Mevlâna Rumi or Yunus Emre, or aphorisms from classics, presented in elegant scripts like thuluth or nasta’liq. Ottoman tughra (the sultan’s calligraphic monogram) and hilya (calligraphic description of Prophet Muhammad) are unique art forms where text is visually embellished to an extraordinary degree. The tughra’s intricate design, essentially writing as abstract pattern, and the hilya’s combination of script with illumination and decorative motifs show how writing itself became a visual art. Here, literature’s influence is intrinsic: the very words are the art. The choice of poem or proverb for a calligraphic panel would be deliberate, indicating themes the patron or artist wished to convey (devotion, wisdom, love), and the style of script would amplify the emotional tone of the text. For instance, a flowing diwani calligraphy might be used to pen a romantic couplet by Ottoman poet Nedim, thus merging poetic sentiment with visual grace. In Ottoman architecture, too, literary content adorns the visual realm, many mosque walls are inscribed with verses from the Quran in majestic calligraphy, effectively integrating sacred literature into the visual and spatial experience of the building.

Moving into the 19th and 20th centuries, as the Ottoman Empire modernized and eventually transformed into the Turkish Republic, literature continued to impact visual arts, albeit in evolving ways. The Tanzimat period (mid-19th century) saw the introduction of Western-style painting and the rise of the first generation of Ottoman painters who created standalone oil paintings. Some of these artists, such as Osman Hamdi Bey, were also intellectuals aware of the literary currents of their time. Osman Hamdi’s famous painting “The Tortoise Trainer” (1906) can be interpreted as an allegory that resonates with social commentary akin to literature, indeed, some view it as a visual satire on the slow pace of Ottoman reform, a theme much discussed in contemporary essays and stories.

In the early Republican era (1920s–1930s), as Turkey forged a new national identity, both literature and art were harnessed to that cause. Atatürk and his circle encouraged a search for a national art style, and many painters drew inspiration from Anatolian village life and folk culture, themes that also pervaded literature of that era (like the novels of Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu or poems of Nazım Hikmet). For example, the “Association of Independent Painters and Sculptors” and the later “D Group” included artists who depicted scenes of Anatolian people, Turkish warriors, or interpreted historical literary themes on canvas. Some painted illustrations for contemporary books or nationalist epics. The Ministry of Culture even sent painters on Anatolian sketching tours (1938–1944) to document and draw inspiration from village scenes; paralleling how writers of the “Village Literature” movement were writing stories set in rural Anatolia around the same time. This synergy meant that visual artists and writers were effectively engaging in a common project of exploring Turkish identity; a novel about a Anatolian farmer’s hardship might find its counterpart in a painting of villagers dancing the halay, for instance.

One fascinating modern example of literature-art interplay is the work of Orhan Pamuk, Turkey’s 2006 Nobel laureate in literature. Pamuk’s novels often engage deeply with Turkey’s visual and artistic heritage. His novel My Name Is Red (1998) is explicitly about Ottoman miniaturists in the 16th century and the clash between Islamic manuscript art and European Renaissance painting. Within the novel, Pamuk vividly describes the philosophies and techniques of miniature painters, essentially embedding an art history lesson in a murder mystery. The novel’s popularity actually spurred renewed interest in Ottoman miniatures among Turkish readers and even inspired artists. My Name Is Red thematically portrays the decline of Ottoman miniaturist painting under the influence of European art – dramatizing how a shift in aesthetic paradigms (from stylized tradition to Western realism) affected individual artists’ identities and lives. Pamuk thereby used literature to explore an art-historical narrative, and in doing so, influenced contemporary discussions on the East-West dichotomy in Turkish art. An essay discussing Pamuk noted that in My Name Is Red, the conflict between Venetian realism and the old miniaturists’ style is a microcosm of Turkey’s identity crisis, and indeed “fills the world” of the novel. This is literature directly mining visual art history for its plot and symbolism. Intriguingly, Pamuk himself later curated a real museum (the Museum of Innocence in Istanbul) to accompany his novel of the same name, blending fiction with a visual art installation; again blurring boundaries between the narrative text and visual experience.

Conversely, modern Turkish visual artists have drawn on literary themes or texts for inspiration. In the mid-20th century, painter Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu incorporated lines of folk poetry into his paintings as calligraphic elements, merging words and images on the canvas. Another contemporary artist, İlhami Atalay, created a series of paintings based on the verses of Yunus Emre, the great 13th-century Turkish Sufi poet, essentially illustrating the emotional landscapes evoked by Yunus’s poems. In theater and cinema (visual arts in motion, so to speak), many works are direct adaptations of literature, for example, several of Yaşar Kemal’s novels (like Memed, My Hawk) have been made into films, and Nazım Hikmet’s epic poem Human Landscapes from My Country inspired visual storytelling on screen. Renowned filmmaker Metin Erksan’s 1966 film Time to Love was deeply poetic in approach and showed the influence of literary sensibilities on visual narrative. Additionally, the rich tradition of Turkish shadow theater (Karagöz), discussed earlier, had its scripts in a sort of crude oral literature, these were later transcribed, and the stock characters of Karagöz plays have appeared in modern paintings and illustrations as quintessential cultural icons. For instance, cartoonists and fine artists alike have depicted Karagöz and Hacivat in artworks commenting on current events, much as a writer might use those characters in a story to reflect on society.

Another dimension of literary influence is the role of literary symbolism and themes in Turkish painting. The Tulip Period of the early 18th century, for example, is named for the craze for tulips in Ottoman culture, tulips were a major motif in poetry symbolizing perfection and divine beauty, and simultaneously appeared in decorative arts, from tiles to textile patterns. In modern times, the melancholy aesthetic concept of hüzün (a kind of Istanbul-specific melancholy that Orhan Pamuk writes about extensively in his memoir Istanbul) has influenced photographers and painters who try to capture the wistful, faded glory of Istanbul’s old streets and Bosphorus vistas. The feeling Pamuk describes in prose has visually manifested in the works of artists like Ara Güler (photographer of old Istanbul) or painters who specialize in sepia-toned cityscapes.

Furthermore, Turkish literature’s narrative techniques have had parallels in visual storytelling. The multi-perspective storytelling common in Turkish novels (used by authors from Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar to Latife Tekin) finds an analogue in the way some modern Turkish artists produce series of paintings or comic-like sequences that explore a theme from multiple angles. The rise of graphic novels in Turkey, for example, merges literary narrative with drawn art – such as the graphic adaptation of Sabahattin Ali’s classic novel Madonna in a Fur Coat or the illustrated poem collections of İlhan Berk.

In sum, Turkish literature and visual arts have long been engaged in a creative conversation. Illustrated manuscripts show the direct pictorial rendering of literary content in Ottoman times. Calligraphy and illumination demonstrate how writing itself became visual art under literary and religious inspiration. In modern contexts, novels and poems provide themes, stories, and emotional landscapes that painters and other visual artists continue to draw upon. The interplay goes both ways: art has also influenced literature, many Turkish writers describe paintings or architecture in detail in their prose, effectively “painting with words” and thereby possibly inspiring readers to see the visuals in their mind’s eye or to visit the actual art. A vivid case is in Pamuk’s The Museum of Innocence, where the protagonist lovingly describes everyday objects in almost curatorial detail, which later became an actual museum exhibit curated by Pamuk; a rare instance where a novelist’s vision literally turned into a visual collection. In the broader cultural panorama, one can conclude that the Turkish imagination does not silo its art forms. Poets write about the Bosporus as if it were a living painting; composers set poems to music; painters illustrate epics; architects inscribe poetry on mosque walls. This interdisciplinary fertilization is a hallmark of Turkish arts.

As a literary scholar might assert, the strength of Turkish storytelling, from the epics of Dede Korkut and the verses of the Mevlevis to the modern novel, has given Turkish visual arts a wealth of iconography and narrative depth to explore. Conversely, the beauty of Turkey’s visual heritage has often prompted reflection in literature, whether it’s Yahya Kemal’s poetic descriptions of Istanbul’s skyline or modern novelist Elif Shafak’s colorful scene-setting. The relationship is ultimately symbiotic: words inspire images, and images inspire words. The continuity of this influence is evident in contemporary Turkey, where you might find a poet referencing an Ara Güler photograph in a poem or a painter titling a work after a line from Orhan Veli. In the tapestry of Turkish culture, literature and visual art are like intertwined threads – distinct yet inseparable in creating the overall design.

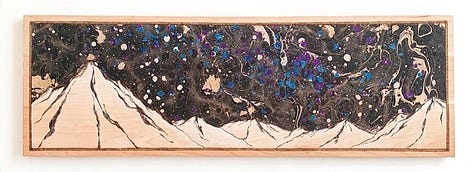

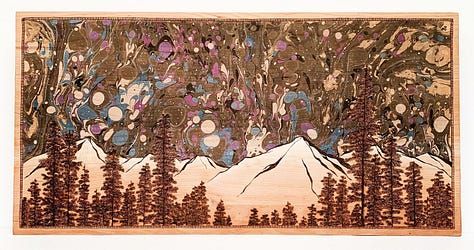

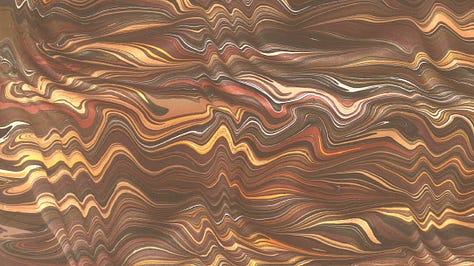

Ebru, the traditional Turkish art of marbling, is a unique form of painting on water that produces mesmerizing swirled patterns transferred onto paper. Often described as “cloud painting” (one possible meaning of ebru or the older term abru), this art form has been practiced in Ottoman Turkey since at least the 15th or 16th century, and it remains a beloved decorative art today. In recognition of its cultural significance, Ebru; Turkish paper marbling was inscribed in 2014 on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. This inclusion by UNESCO highlights not only the beauty of ebru but also its role in Turkish identity and its transmission across generations.

The process of ebru is itself an artistic performance. The practitioner begins with a shallow tray filled with water that has been mixed with a gelling agent (traditionally kitre, a gum tragacanth that thickens the water). On this dense water surface, ebru artists sprinkle and deftly brush pigments that float upon the surface. These pigments are prepared by mixing natural color powders (from mineral or earth pigments) with water and adding ox-gall, a surfactant from cattle, which helps the paint spread and float. The artist might drip one color, then another, watching how the dots of paint expand into floating circles. Using tools like styluses, combs, or brushes, the artist then manipulates these colors, combing them into waves or plumes, or dragging a stylus to create feathery tendrils. Within moments, complex patterns emerge: peacock-like swirls, floral motifs that seem to bloom on water, or intricate feathery designs reminiscent of a kaleidoscope. Common traditional patterns have names like gelgit (to-and-fro, a sweeping marble), tarakli (combed), or bülbül yuvası (nightingale’s nest, a motif of concentric swirls). One celebrated variety is the floral ebru, where the artist skillfully adds and shapes colors to form distinct images of flowers (tulips, carnations, roses) floating amid the marbled backdrop. It’s astonishing to witness: the water’s surface becomes a canvas where each movement of the brush or pen creates a new shape in real-time.

When the design is complete, the artist gently lays a sheet of paper on top of the water, then just as gently lifts it. By the magic of surface tension, the entire intricate design instantly transfers onto the paper, fixing the previously fluid art into a permanent form. The paper is then rinsed and dried, capturing the once-in-motion painting as a lasting artwork. No two ebru pieces are ever identical, the medium inherently produces one-of-a-kind results, which is part of its charm. As the UNESCO description states, “Ebru is the traditional Turkish art of creating colourful patterns by sprinkling and brushing color pigments onto a pan of oily water and then transferring the patterns to paper”. The resulting designs can include “flowers, foliage, ornamentation, latticework, mosques and moons” among others. This indicates that beyond abstract patterns, marblers have developed figurative techniques as well (like the floral ebru mentioned).

Historically, ebru was often used to decorate the endpapers of books, especially calligraphy albums and manuscripts, as well as for hat (calligraphic panels) backgrounds, giving a splendid backdrop to the text. It prevented forgery (since each pattern is unique) and added beauty to books. Marbled paper from Ottoman workshops was also a trade item, sold to Europe (where it became known as “Turkish marbled paper” and was used in bookbinding). The art likely has roots and connections with similar practices in Persia or Central Asia, but the Turks developed it into a distinctive art form with recognizable styles.

The cultural aspect of ebru is notable. For many marblers and enthusiasts, the art carries a almost meditative, philosophical aspect. The marbling process requires patience, a steady hand, and a harmony with the materials ; water, paint, and paper. In a master-apprentice setting, learning ebru traditionally takes at least two years to grasp the basics. The apprentice learns how to prepare the marbling size (water solution), how to grind pigments finely, how much ox-gall to add for the desired spread (this can vary by weather and water quality, so it’s a skill of intuition), and how to wield tools to create both classic and innovative patterns. Through informal training and practice, the knowledge is transmitted, often within families or small guilds of artists. A remarkable point is that ebru has historically been a democratic art form in terms of participation; it is practiced by people irrespective of age, gender, or ethnicity in Turkey. In the Ottoman era, some known ebru masters were judges or imams by profession who did marbling as a hobby, as well as artisans devoted solely to it; today there are both amateur hobbyists and renowned professional ebru artists in Turkey keeping the art alive.

There is also a social and communal dimension; Ebru workshops encourage dialogue and interaction. The UNESCO dossier noted that “the collective art of Ebru encourages dialogue through friendly conversation, reinforces social ties and strengthens relations between individuals and communities”. This is observable in modern Turkey where community centers or art schools offer ebru classes; you might see a group of schoolchildren marveling around a water tray during a demonstration, or adult students chatting about daily life while grinding pigments. Because each person’s result is unique yet all stemming from the same water and colors in the tray, ebru has a way of connecting people; everyone faces the same delightful unpredictability, and there is often a sense of shared joy when a beautiful marbled paper is pulled out.

Artistically, ebru has inspired modern applications as well. Contemporary artists sometimes use marbling techniques on fabrics, wood, or even glass. Fashion designers have printed marbled patterns onto textiles, and marbling art has even been digitized for graphic design purposes. Yet traditionalists maintain the pure form with natural methods. One celebrated modern ebru master, Mustafa Düzgünman (1920–1990), is credited with reviving and preserving many classical techniques and training a new generation of marblers, ensuring the continuity of the art into the 21st century.

The aesthetics of ebru, its ethereal, fractal-like swirls, have made it a metaphor in Turkish culture for grace and fluidity. Phrases like “ebru gibi” (like marbling) might be used to describe something intricately patterned or beautifully variegated. The word Ebru itself, interestingly, can also mean “eyebrow” in Persian, or “water surface”,both hinting at beauty. There is even a traditional female name “Ebru,” symbolizing a refined beauty, presumably drawing on the delicate art.

In literature and poetry, marbling has been referenced symbolically. Ottoman poets occasionally likened the play of colors in a sunset or the variegation of a tulip’s petals to ebru, thus using art to describe nature’s art. Conversely, some ebru artists take inspiration from literature; for instance, a marbler might create a series of works each named after a line of Rumi’s poetry, trying to capture that emotion in the flow of colors.

What makes ebru particularly intriguing as an art form is that it sits at the crossroads of control and serendipity. The artist must master control,.knowing how each flick of the brush will roughly behave,.yet also must embrace the spontaneous interactions of pigment and water that cannot be fully predicted. This balance is almost philosophical: it teaches patience, humility (as the water might decide to do something different than intended), and delight in unexpected beauty. Many ebru artists speak of a sense of calm and focus when they practice, akin to a form of art therapy. Because of this introspective quality, ebru was historically practiced by some members of dervish orders and is sometimes associated with a spiritual mindset.

In the modern global art scene, ebru has gained fans beyond Turkey’s borders. Artists around the world have been inspired by Turkish marbling and adapted it to their contexts. However, Turkey remains the heart of this tradition, with ongoing festivals, exhibitions, and competitions celebrating marbling. In Istanbul, one can visit the Turkish Marbling Museum (Ebru Evi) and various ateliers. The inclusion in UNESCO’s list in 2014 explicitly recognized Turkey’s leadership in safeguarding this art, which was identified as the 12th cultural element from Turkey to be so listed.

Ebru is a shining example of a Turkish art form that is at once traditional and timeless. It encapsulates the ingenuity of transforming simple elements (water, pigment, paper) into works of exquisite complexity and beauty. As an art of creation that literally captures the movement of life (flowing water) into a static form, it’s often seen as symbolic of capturing a moment in time, a dance of colors frozen by the artist’s touch. This art of Turkish marbling continues to enchant new generations, ensuring that the marbled patterns that adorned the pages of Ottoman books centuries ago will continue to bloom on new sheets of paper in the future, each one a singular and unrepeatable marvel of art on water.

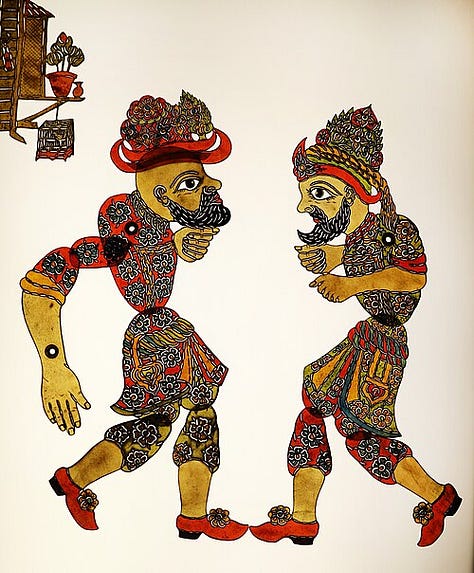

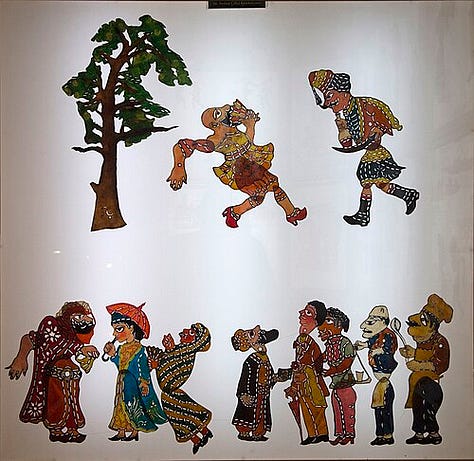

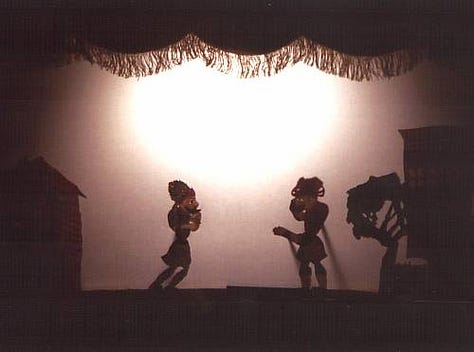

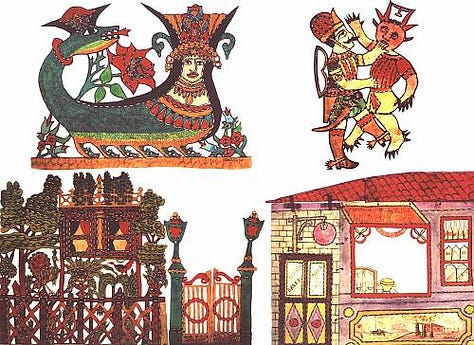

Karagöz, the traditional Turkish shadow puppet theater, is a form of storytelling and performing art that combines visual creativity with comic literature and music. It centers on the humorous adventures of its two titular characters: Karagöz (literally “Black-Eye”), a boisterous, uneducated everyman known for his crude wit, and Hacivat, his learned friend whose refined language and manners comically clash with Karagöz’s coarse humor. Originating in the Ottoman period (with popular lore placing its emergence in the 14th century in Bursa, though it likely developed fully by the 16th–17th centuries), Karagöz theater became one of the most beloved entertainments of Turkish popular culture. Its influence and appeal were so great that UNESCO recognized Karagöz shadow theatre as Intangible Cultural Heritage (inscribed in 2009), acknowledging its cultural significance across generations.

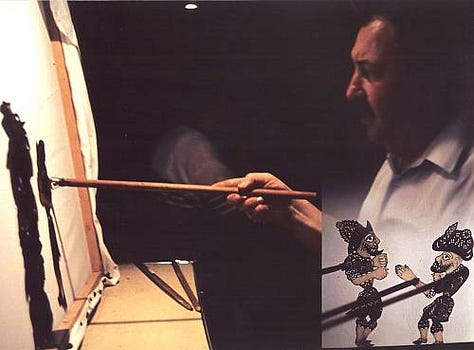

The art of Karagöz is distinctive for its medium; colorful puppets crafted from camel or water buffalo hide, carefully cut and painted to represent various characters, and articulated with joints so they can move. These puppets, known as tasvirs, are held on rods and pressed against a lit screen (traditionally a white cotton cloth called ayna or mirror) to cast their shadows to the audience’s view. The puppeteer, called the Hayalî (imagist or dreamer), stands behind the screen and single-handedly voices and manipulates all the characters, often with the help of one or two apprentices who might provide sound effects or music. A defining feature of Karagöz plays is their improvisational nature, while there is a repertoire of known storyline scenarios and stock jokes, much of the dialogue is extemporized, allowing the Hayalî to incorporate current events, local slang, and spontaneous humor.

A typical Karagöz performance follows a structure: it opens with a musical introduction and the appearance of a distinctive narrator figure (the Hacivad puppet often fills this role initially) or a scene-setting puppet, then the main play unfolds with Karagöz and Hacivat bantering and encountering a series of other comic characters, and ends with a closing, usually Karagöz apologizing to the audience for any offense and promising to do better (a tongue-in-cheek convention). The content is richly humorous, often satirical. Puns, wordplay, and mimicry are staples of the dialogue. Karagöz, with his straightforward and often foolish interpretations of Hacivat’s polite or learned speech, provides slapstick and linguistic comedy. Meanwhile, the various other characters represent the diversity of the Ottoman urban scene; there are standard figures such as a bearded Turk from Ankara, an Albanian guard, a drunken Levantine European, a Jewish moneylender, an Arab trader, an Armenian grocer, a flirtatious courtesan, a braggart soldier, etc. Each speaks in a caricatured accent and exhibits exaggerated stereotypes that, while products of their time, made audiences laugh at the foibles of every community (in a way, it both highlighted and good-naturedly mocked the multi-ethnic makeup of the society). For instance, one might see Karagöz miscommunicate with a Turkish countryside peasant character because of dialect differences, or Hacivat trying to maintain decorum while a Roma (Gypsy) character plays raucous music, such interactions offered ripe ground for comedy and also a subtle social commentary on harmony and conflict among the empire’s peoples.

Musically, a tambourine (def) and other instruments like a fiddle or clarinet often accompany the action. Songs might be interjected, and there are sometimes dance interludes by puppets (especially if a “Kantocu” character, a cabaret singer appears, as noted in descriptions). These multi-art elements, music, voice acting, visual puppetry, make Karagöz a truly multimedia folk art.

Karagöz plays traditionally were performed at night, often during the month of Ramadan after the evening fast, when people would gather in coffeehouses, open courtyards, or private homes for entertainment until the early hours. They were also a feature of circumcision festivities for children of elites (and commoners), and other celebrations. In the Ottoman golden era, even sultans enjoyed Karagöz shows, though the content was very bawdy and irreverent. In fact, the humor could be quite ribald, full of innuendo and scatological jokes; things that ordinary people loved but that sometimes got the genre censured by moralists. Despite occasional disapproval by authorities or clergy for its crudeness, Karagöz thrived precisely because it was the voice of the common folk, allowed to say and do on stage what people could not in polite society.

Importantly, Karagöz provided a vehicle for social and political satire. Because it was “just shadow play,” puppeteers had a degree of license to poke fun at the ruling class or comment on topical issues with less fear of retribution. The puppets could make pointed remarks about a local official’s corruption or lampoon a new fashion among the elite. As a scholar on Ottoman theater notes, “the performances of karagöz at nineteenth-century Ottoman coffeehouses were full of political satire, and high officials and grand viziers were fair game”. Thus, Karagöz served as a kind of pressure valve for society, using comedy as a means to express public opinion. The tradition that government spies would attend coffeehouses to gauge public sentiment reinforces how influential and informative such plays were.

With the advent of modern entertainment (cinema, radio, then television) in the 20th century, Karagöz’s popularity waned to some extent, but it never disappeared. Efforts by folklorists and artists in the early Republic kept it alive, albeit often in a cleaned-up form more suitable for family audiences and national culture presentations. Today, Karagöz is considered an important part of Turkey’s cultural heritage, and performances can be seen at cultural festivals, in tourist settings, and occasionally on television as children’s programs. Hayali masters still train in the traditional ways, learning the voices, jokes, and crafting of puppets. UNESCO’s recognition in 2009 (and the detailed Silk Roads Programme description) emphasizes its continued presence: “Once played widely at coffeehouses, gardens, and public squares, especially during the holy month of Ramazan…. Karagöz is found today mostly in performance halls, schools and malls in larger cities where it still draws audiences. The traditional theatre strengthens a sense of cultural identity while bringing people closer together through entertainment”. Indeed, modern performances aim to instill an appreciation for this heritage in younger generations, often with slight modifications (e.g., toning down some of the old jokes) but retaining the core characters and humor.

Visually, the art of Karagöz puppets has inspired Turkish graphic arts as well. The brightly colored figures (often dyed with vegetal colors that glow beautifully when backlit on the screen) and their stylized features have been the subject of painters and illustrators. One can find Karagöz and Hacivat depicted in modern cartoons, book illustrations, even logos for festivals, attesting to their iconic status. They are to Turkey what Punch and Judy are to England, or what commedia dell’arte characters are to Italy; emblematic archetypes from traditional theater. The shadow play technique also intriguingly parallels the idea of early cinema (moving silhouetted figures), which perhaps is why it can still enchant audiences accustomed to screens.

From a scholarly perspective, Karagöz is a valuable window into Ottoman society’s values, prejudices, and humor. The plays preserved by researchers capture the vernacular speech patterns and comedic sensibilities of bygone eras. For example, a recurring gag might be Karagöz mispronouncing flowery Persian-Arabic words that Hacivat uses (poking fun at linguistic snobbery), or Hacivat trying to engage Karagöz in a learned discussion only to have Karagöz twist the meaning into something vulgar; such skits implicitly critiqued class differences in education. Another frequent plot is Karagöz attempting some job or craft he is ill-suited for, messing it up hilariously (a trope that makes a statement about incompetence and perhaps the everyman’s struggle). These themes are timeless in their appeal and continue to evoke laughter.

Moreover, Karagöz has transcended Turkish borders historically, variations of the shadow puppetry spread through the Ottoman Empire into North Africa (e.g., in Tunisia and Algeria a similar character called Karagoz existed) and the Middle East, and many believe it has older cousins in Chinese and Southeast Asian shadow puppet traditions. But the Turkish Karagöz is distinct for its slapstick and urban satire flavor.

In modern Turkey, beyond the stage, Karagöz and Hacivat have even been protagonists in films and literature. A noteworthy example is the 2006 Turkish film “Hacivat ve Karagöz Neden Öldürüldü?” (“Who killed Hacivat and Karagöz?”), which is a historical drama imagining the origins of the characters in the 14th century and reflecting on freedom of speech. This indicates that the figures still occupy a place in the collective imagination and can be used metaphorically to comment on present issues (the film, for instance, subtly comments on religious intolerance and censorship, through the lens of history).

Ultimately, Karagöz is cherished not only as lighthearted entertainment but as a key part of Turkey’s intangible cultural heritage, carrying forward an oral performance tradition that links the present to the Ottoman past. It exemplifies how art in Turkey has often existed in the coffeehouses and commons, as much as in palaces or formal theaters; a people’s art. The durability of Karagöz is a testament to the Turkish love of wit and satire, and to the adaptability of traditional arts. Today’s audiences, watching a Karagöz show in a school auditorium, might laugh at slightly updated jokes (perhaps Karagöz dealing with a cell phone or Hacivat quoting a line from a popular TV series), but they are essentially laughing at the same comedic types that amused Ottoman audiences centuries ago. The shadows on the screen have life and resonance beyond their two-dimensional form, embodying a continuity of cultural expression. In a fast-changing world, Karagöz’s lamp-lit stage reminds us that sometimes the simplest means, a screen, a lamp, and imagination, can create laughter and bring people together, just as effectively now as in times past.

The late 19th and 20th centuries brought seismic changes to Turkish art as the country grappled with Westernization, modernity, and the forging of a national identity. Modern Turkish art is characterized by an ongoing tension and interplay between embracing Western artistic trends and rediscovering or reinventing indigenous forms to express a new national consciousness. From the decline of the Ottoman Empire through the establishment of the Republic of Turkey and into contemporary times, Turkish artists have navigated influences from Europe while also seeking to assert what is uniquely Turkish in their work.

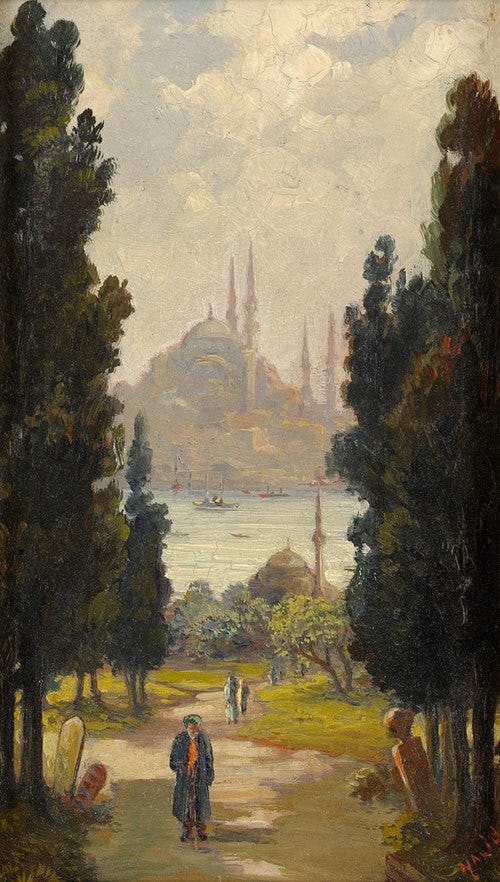

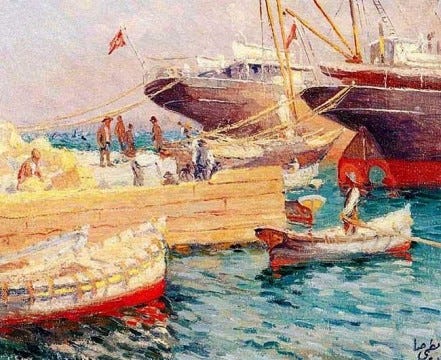

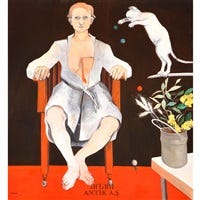

In the 18th and 19th centuries, during the twilight of Ottoman rule, there was a visible shift in art and architecture under increasing European influence. The Ottoman elite, in an effort to modernize, adopted Baroque and Rococo motifs in architecture and decorative arts, resulting in what some historians describe as “over-elaborated and fussy detail” in late Ottoman ornamentation. For example, palaces like Dolmabahçe (built mid-19th century) and Ortaköy Mosque (1850s) on the Bosphorus featured neoclassical and Baroque designs, a marked departure from the traditional Islamic-Ottoman aesthetic. Painting, which had been mostly limited to miniatures, also began to change. European-style painting (with perspective, shading, oil on canvas) was slow to gain acceptance in Ottoman Turkey, partly due to Islamic aniconic sensitivities and the lack of institutions for fine arts education. However, by the mid-19th century, a few Ottoman intellectuals and officials emerged as painters, often having studied abroad. The most prominent was Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910), who studied painting in Paris and later became the founding director of the Imperial Museum and the Academy of Fine Arts (Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi) in Istanbul. Osman Hamdi’s paintings, like the famous “The Tortoise Trainer” or “Girl Reading the Quran,” are emblematic: technically aligned with European academic realism/orientalism, yet offering insider critiques of Ottoman society and orientalist clichés. He and his contemporaries (such as Şeker Ahmet Paşa and Halil Pasha) were somewhat solitary figures in a society still unaccustomed to representational painting, but they laid the groundwork for a new art movement. Their experience symbolized the early Western influence on Turkish art; trained in Europe, bringing back new techniques, and often painting subjects that negotiated the encounter of East and West (Hamdi Bey’s works, for instance, often deliberately countered the way Western Orientalist painters depicted Ottoman subjects by giving a more introspective or critical view from “the inside”).

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of the Turkish Republic in 1923, there was a conscious drive to “reset” the cultural orientation of the nation towards a secular, Western-facing future while also cultivating a distinct Turkish identity. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s reforms affected language, dress, education, and naturally, the arts. The new Republic’s leaders saw art as a means to project modernity and nationalism. Artists and politicians alike called for a new kind of art to represent the fledgling nation, rejecting the last ornamental excesses of late Ottoman art. However, there was no single manifesto of what Turkish art should look like; instead, multiple schools and movements emerged in the early Republican era, reflecting different balances of Western influence versus local themes.

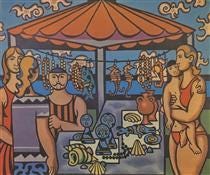

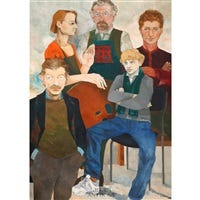

During the 1920s and 1930s, two notable art groups formed. The Association of Independent Painters and Sculptors (1928) leaned towards folkloric and national subjects. Artists like İbrahim Çallı, Nazmi Ziya Güran, and Turgut Zaim in this milieu often painted landscapes of Anatolia, scenes of village life, or historical episodes from the Turkish War of Independence. Their style was representational, sometimes impressionistic (as many had studied in Europe during the 1910s and were influenced by late Impressionism or Fauvism), but the content was chosen to resonate with Turkish identity and pride in the homeland. Paintings of hearty Anatolian peasants dancing, or equestrian portraits of Atatürk, or scenes from Istanbul’s neighborhoods can be seen as an attempt to indigenize Western painting techniques by applying them to Turkish themes.

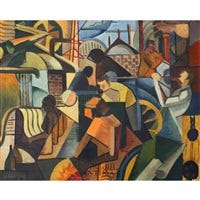

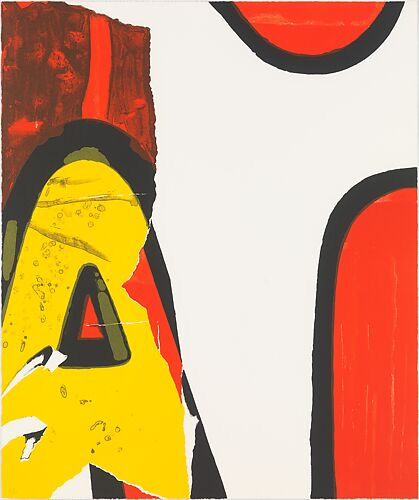

On the other hand, the D Group (founded 1933) was more avante-garde and cosmopolitan, comprising artists like Zeki Kocamemi, Cemal Tollu, Nurullah Berk, and others. They were “heterogeneous” in style, some experimenting with Cubism and Constructivism, others blending European modernist styles with hints of traditional motifs. For example, Nurullah Berk produced semi-abstract paintings that incorporated Anatolian carpet patterns or calligraphic shapes, effectively early attempts at synthesizing Western modernism with Turkish elements. Another D Group member, Abidin Dino, absorbed influences of social realism and later abstract expressionism, often with political undertones linked to class struggles or the condition of Anatolian people (reflecting the leftist literary movement at the time). We see here an interesting phenomenon; these modern artists sought to be on the cutting edge of global art, yet could not escape (nor did they want to) the question of national identity in their work.

The Turkish state actively sponsored art as well. Atatürk’s government sent young artists to Europe on scholarships and invited European artists to Turkey to teach. Notably, German sculptor Rudolf Belling headed the sculpture department in Istanbul in the late 1930s, and other foreigners taught architecture and painting. The result was that the first generation of Turkish sculptors and modern architects emerged, creating public monuments and buildings in international styles but often with subtle national references. Sculpture, previously negligible in Ottoman times due to religious aniconism, now became a state-sponsored art, mainly to produce heroic statues of Atatürk and War of Independence memorials. Indeed, one sees in practically every city in Turkey a 1930s–1950s era statue of Atatürk, often in a Soviet-style or neoclassical realist style, underscoring how visual art served to cement national narrative and venerate the Republic’s founder. As the Wikipedia summary of Turkish art aptly puts it, “sculpture is less developed, and public monuments are usually heroic representations of Atatürk and events from the war of independence”.

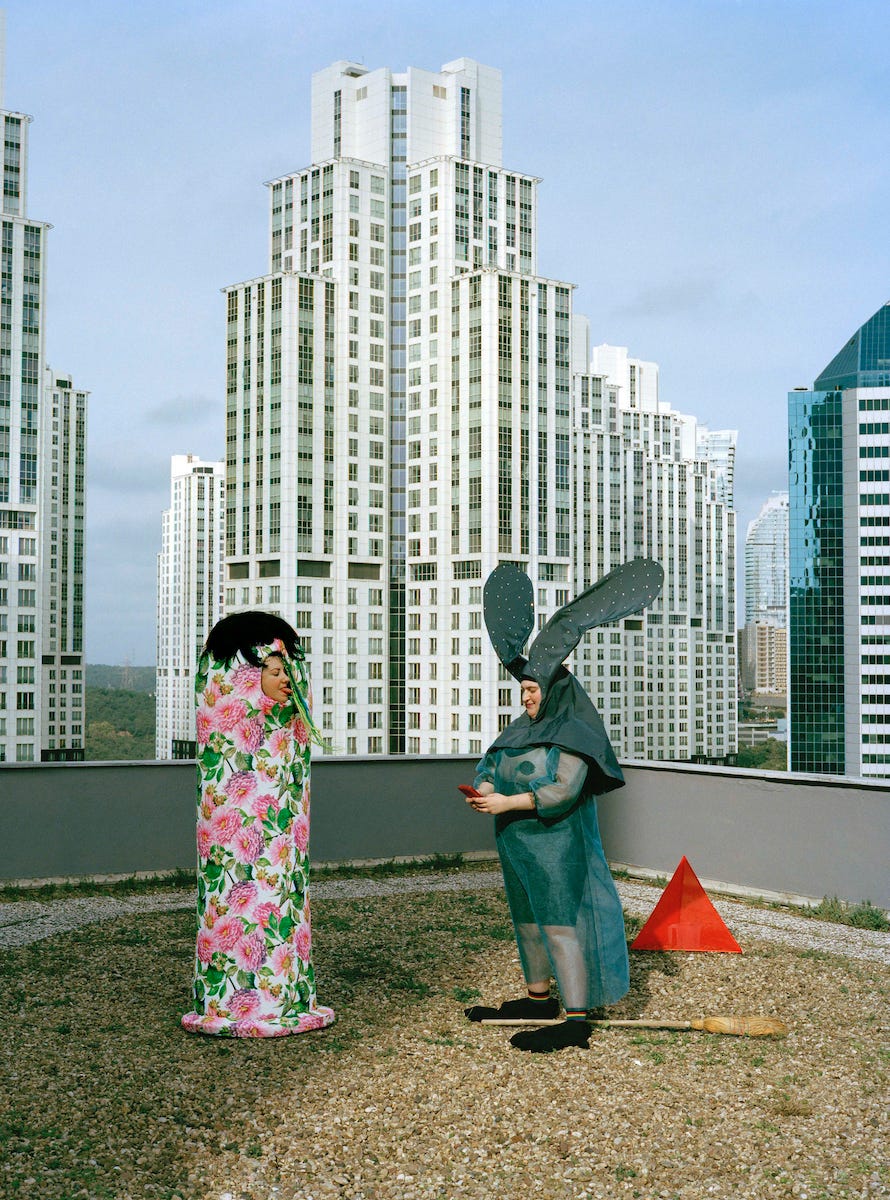

While Western artistic idioms were being adopted, there was simultaneously a desire to link modern Turkey to its deep past (pre-Ottoman) to create a national continuity. This was reflected in art and architecture by what is called the “First National Architectural Movement” in the 1920s, which blended Ottoman and Seljuk revival elements with neoclassicism in government buildings (e.g., Ankara’s first parliament building or early banks). Later, a “Second National Movement” in the 1930s-40s emphasized more Anatolian vernacular elements. Painters similarly sometimes drew on Hittite or Phrygian motifs (archaeology was glorified by the state as uncovering ancient Turkish roots). This search for a unique national style sometimes meant a romanticization of folk art; for instance, artists like Turgut Zaim painted in a naive style echoing folk embroidery and miniature painting. Atatürk’s cultural policies also led to People’s Houses (Halkevleri) around the country where local art and folklore were collected and displayed. Painters were sent to villages to capture scenes of traditional life (the Provincial Painting Tours mentioned, 1938–44), which resulted in many artworks depicting, say, Central Anatolian flatlands with ox-carts, or Black Sea villagers, etc. This imagery paralleled the “Yurt Gezileri” (Homeland Tours) literature initiative where writers and photographers documented life in all regions of Turkey.