Art has served as a mirror of human experience, reflecting societal transformations, spiritual beliefs, and technological advancements throughout history. The evolution of art spans millennia, with each major period and movement introducing distinctive themes, styles, and techniques.

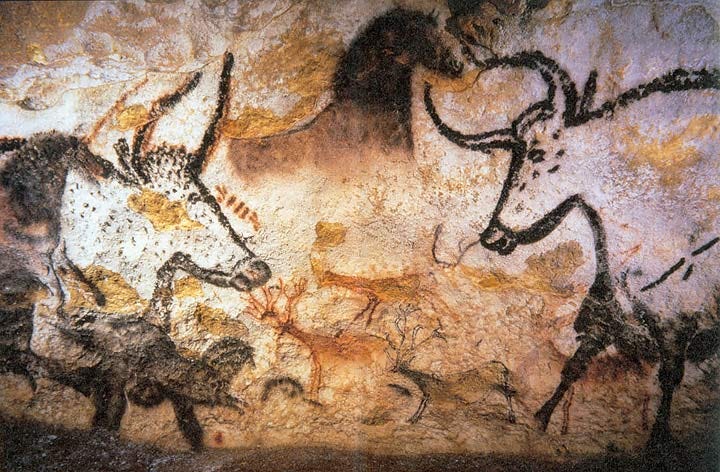

Prehistoric art marks the beginning of humanity's creative endeavors, encompassing the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic periods. These early expressions of art reveal a deep connection to nature, spirituality, and survival. The Cave Paintings of Lascaux (ca. 15,000 BCE) in France depict animals such as bulls, horses, and deer, believed to be part of hunting rituals or shamanistic practices (Clottes 28). The Venus of Willendorf (ca. 28,000–25,000 BCE), a small limestone figurine, symbolizes fertility and abundance, with its exaggerated feminine features reflecting early human concerns with reproduction and sustenance (Mithen 134).

The Neolithic period saw the emergence of monumental architecture, such as Stonehenge (ca. 3000 BCE) in England, constructed using massive stones aligned with the solstices. This structure underscores the sophisticated astronomical knowledge and communal organization of its creators. Prehistoric art reflects humanity's first attempts to understand and shape the world through visual representation.

The ancient world (ca. 3000 BCE–500 CE) witnessed the rise of civilizations such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome, each contributing significantly to the development of art. Egyptian art emphasized the afterlife and divine authority, as seen in the Great Pyramid of Giza (ca. 2560 BCE) and the Bust of Nefertiti (ca. 1345 BCE), which exemplifies idealized beauty and royal power (Boardman 47).

Mesopotamian art often combined utilitarian and religious purposes. The Code of Hammurabi (ca. 1754 BCE) features a legal text inscribed on a basalt stele, topped with a relief depicting King Hammurabi receiving laws from the sun god Shamash (Honour and Fleming 58). This synthesis of art and governance underscores the interconnectedness of religion and politics in ancient societies.

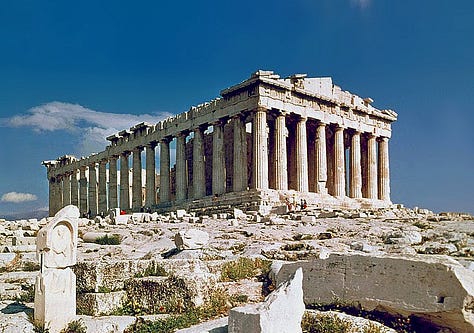

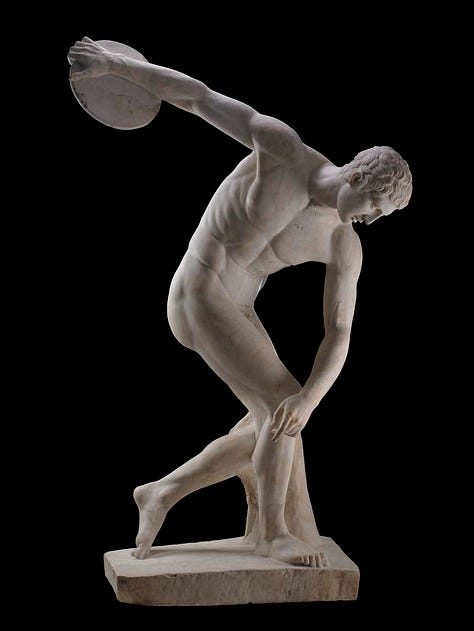

Greek art introduced naturalism and the celebration of human achievement. The Parthenon (447–432 BCE), a temple dedicated to Athena, represents architectural innovation and civic pride. Sculptures like the Discobolus (5th century BCE) by Myron highlight anatomical precision and dynamic movement. The Hellenistic period brought emotional depth to art, as exemplified by the Laocoön and His Sons (2nd century BCE), a marble sculpture capturing the anguish of a Trojan priest and his sons attacked by sea serpents (Boardman 93).

Roman art and architecture emphasized practicality and grandeur. The Pantheon (126 CE), with its massive dome and oculus, reflects Roman engineering prowess and spiritual inclusivity. Roman portraiture, such as the Augustus of Prima Porta (1st century CE), combined realism and idealism to convey political authority. The ancient period laid the foundation for Western art, blending technical innovation with cultural expression.

The Medieval era (500–1400 CE) saw art heavily influenced by Christianity and the Byzantine Empire. Early Christian art, such as the mosaics of Hagia Sophia (537 CE) in Constantinople, used shimmering gold tiles to evoke divine light and spiritual transcendence (Cormack 78).

The Romanesque style (ca. 1000–1200 CE) focused on religious themes and monumental architecture. The Bayeux Tapestry (1070s), an embroidered narrative depicting the Norman conquest of England, demonstrates the integration of historical documentation and artistic craftsmanship (Honour and Fleming 124).

The Gothic period (ca. 1200–1400 CE) introduced innovations such as pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses, allowing for taller, light-filled structures. The Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris exemplifies these advancements, with its intricate stained glass windows narrating biblical stories. Gothic art emphasized spirituality and emotional connection, reflecting the central role of the Church in medieval life.

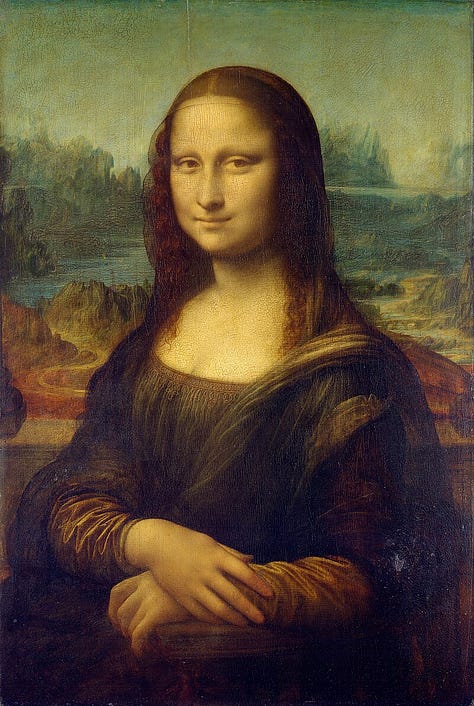

The Renaissance (1400–1600 CE) marked a cultural revival fueled by humanism and a renewed interest in classical antiquity. Artists sought to portray the human experience with realism and emotion, advancing techniques such as linear perspective and chiaroscuro.

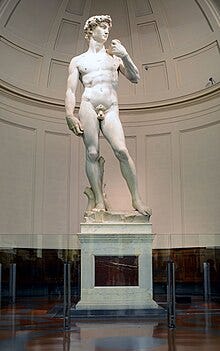

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503) epitomizes the period with its subtle sfumato technique and enigmatic expression, while Michelangelo’s David (1501–1504) captures the idealized human form in marble, symbolizing civic pride and spiritual transcendence. Raphael’s School of Athens (1510) celebrates intellectual achievement, depicting ancient philosophers in a harmonious composition (Vasari 176).

The Renaissance also saw the flourishing of Northern European art. Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) demonstrates meticulous attention to detail and symbolic elements, showcasing the region’s preference for oil painting and domestic themes. This period profoundly influenced the trajectory of Western art, blending scientific inquiry with artistic innovation.

The Baroque (1600–1750 CE) and Rococo (1700–1780 CE) periods emphasized drama, emotion, and ornamentation. Baroque art, as seen in Caravaggio’s The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600), used chiaroscuro to heighten the emotional impact of religious narratives. Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–1652) captures divine rapture in marble, blending realism with theatricality (Blunt 86).

Rococo art, in contrast, adopted a lighter, more playful style. Fragonard’s The Swing (1767) reflects themes of romance and leisure, with its pastel palette and intricate details. These movements mirror the shifting tastes of European patrons, from the solemnity of Baroque to the frivolity of Rococo.

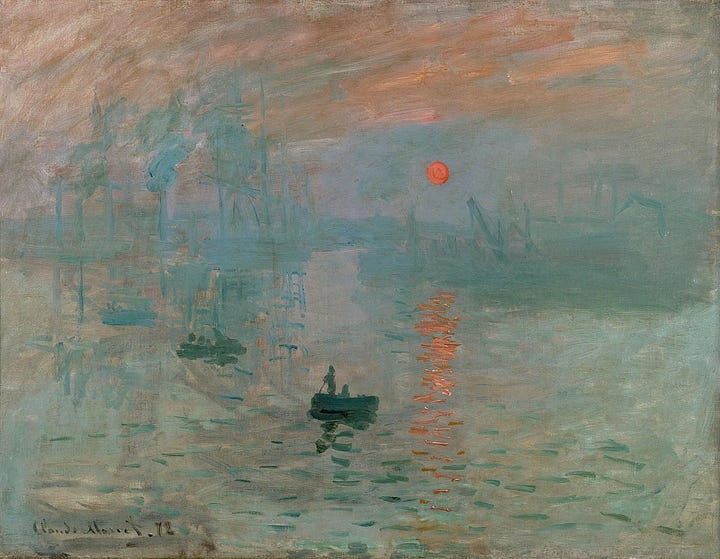

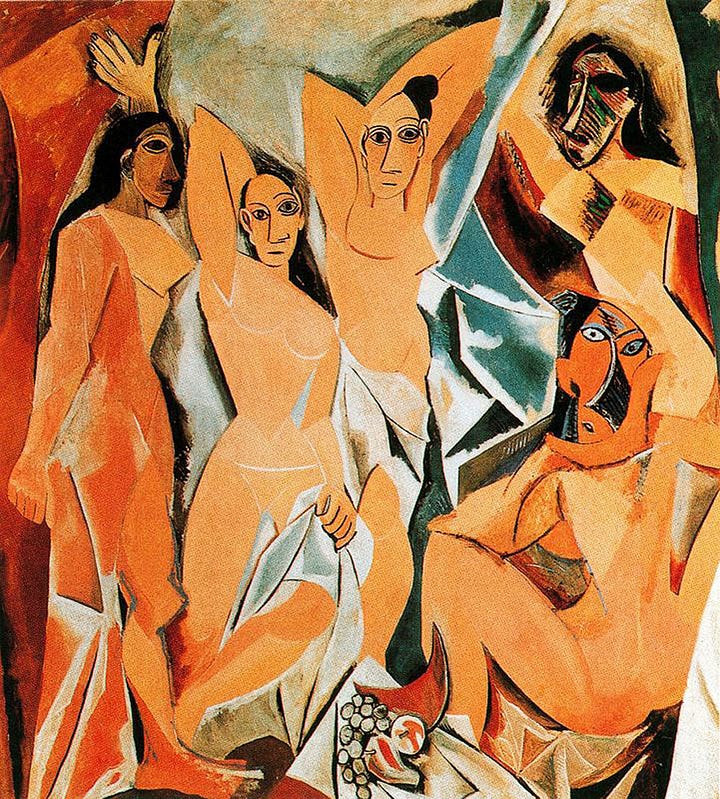

Modern art (1860–1970 CE) challenged traditional conventions, exploring abstraction and new media. Impressionism, led by Claude Monet, captured the fleeting effects of light, as seen in Impression, Sunrise (1872). Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso, deconstructed objects into geometric forms, exemplified by Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) (Stallabrass 45).

Contemporary art (1970–present) embraces diverse media and global perspectives. Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room (2013) immerses viewers in meditative explorations of space and self, while Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2010) critiques mass production and identity through installation art. Contemporary art reflects the complexities of modern society, pushing boundaries and redefining the role of art in a globalized world.

References:

Blunt, Anthony. Baroque and Rococo: Architecture and Decoration. Harper & Row, 1978.

Boardman, John. Greek Art. Thames & Hudson, 1996.

Clark, Kenneth. Civilisation. Harper & Row, 1969.

Clottes, Jean. Cave Art. Phaidon Press, 2010.

Cormack, Robin. Byzantine Art. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Honour, Hugh, and John Fleming. A World History of Art. Laurence King Publishing, 2009.

Mithen, Steven. The Prehistory of the Mind: The Cognitive Origins of Art and Science. Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Stallabrass, Julian. Contemporary Art: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Vasari, Giorgio. The Lives of the Artists. Penguin Classics, 1998.

How totally EPIC⁉️

Insane really. This post should be up for the Oscars of Substack ✨🏆✨

This really is rather wonderful. I have saved it and will return to it if I ever get invited to a dinner party ... you know, so that I can sound intelligent when the hors d'oeuvres are being passed around.