Mardi Gras, French for “Fat Tuesday”, has come to symbolize the exuberant parades, elaborate costumes, and masked revelry of New Orleans. Yet the modern spectacle is rooted in a long history that spans several millennia and continents. Originating in the ritual feasts of ancient Rome and later reinterpreted by medieval Europeans as a final day of indulgence before Lent, the celebration was carried to North America by French colonists. In Louisiana, diverse cultural influences from French, Spanish, African, Caribbean, and Native American traditions converged to shape Mardi Gras into an event that is both a celebration of life and a complex cultural commentary. Today, Mardi Gras remains not only a major tourist attraction and economic engine but also a living tradition that embodies themes of communal identity, resistance against oppression, and the blending of sacred and secular practices.

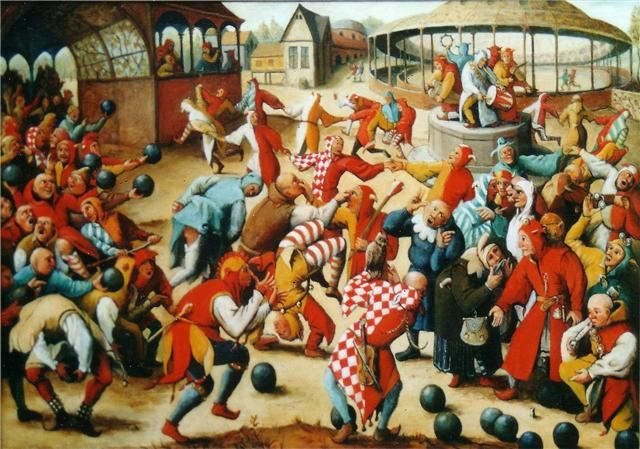

The roots of Mardi Gras can be traced to ancient pagan rituals, particularly the Roman festival of Saturnalia and the spring fertility rites such as Lupercalia. During Saturnalia, social hierarchies were upended and revelry was encouraged; a tradition that later influenced medieval European Carnival celebrations. Medieval scholars have noted that these festivities offered a temporary suspension of social order and a space for subversive humor (Bakhtin 85). In medieval France, the “feast of fools” and the practice of mumming provided further precedent for the inversion of norms, a theme central to modern Carnival (Van Gennep 110).

In addition to these broad cultural currents, European Carnival traditions also featured elements such as masquerading and role reversal, practices that would later be fundamental to Mardi Gras. For example, Wassailing and mumming, observed in rural communities, allowed common folk to mock their betters, echoing a tradition of sanctioned transgression (Costello, Carnival in Louisiana 23). These early practices set the stage for the incorporation of similar elements in the New World.

French exploration and settlement brought Mardi Gras to North America. In 1699, Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and his men celebrated a modest Mardi Gras on what would later be called Pointe du Mardi Gras (History.com Editors). Early records attest that both free and enslaved individuals participated in masquerade balls, street processions, and communal feasts; a practice that found a natural home at places such as Congo Square in New Orleans (Mitchell 25).

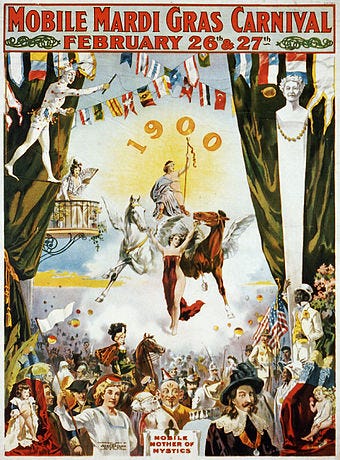

The early colonial period in Louisiana witnessed the blending of French traditions with the cultural practices of enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples. Scholars like Reid Mitchell emphasize that the duality of elite masquerade balls and grassroots revelries laid a complex cultural foundation. This syncretism is also noted in accounts of early Carnival celebrations in Mobile, where French colonial traditions merged with local customs to create a unique festive atmosphere (White; Hoyt-Goldsmith and Migdale).

Following the Treaty of Paris in 1763, Louisiana passed from French to Spanish control. Under Spanish rule, many of the exuberant French Carnival traditions were suppressed. For example, public masquerade balls were curtailed and restrictions were imposed on the wearing of masks by people of color (Mardi Gras – A French Celebration). Despite these prohibitions, clandestine celebrations continued, and the seeds of cultural resistance were sown.

When the United States acquired Louisiana in 1803 through the Louisiana Purchase, these restrictions gradually eased. By the early 19th century, New Orleans had revived its public masked balls and parades. The formalization of the celebration accelerated with the founding of secret societies, or “krewes”, such as the Mistick Krewe of Comus in 1857. As Reid Mitchell explains, Comus introduced torch-lit processions and thematic floats that transformed Mardi Gras into a highly organized public event (Mitchell 27). Samuel Kinser’s Carnival American Style: Mardi Gras at New Orleans and Mobile further documents how these changes paralleled shifting social and economic power dynamics in Louisiana (Kinser 40). Meanwhile, studies by Jennifer Atkins on Carnival balls reveal that these developments laid the groundwork for both the cultural valorization and commercial exploitation of Mardi Gras (Atkins 15).

New Orleans emerged as the epicenter of Mardi Gras in the United States. The city’s celebration evolved into a sophisticated display of cultural identity, social hierarchy, and economic dynamism. The establishment of krewes such as Comus, Rex, and later super-krewes like Bacchus formalized the traditions of parading, masquerading, and the exchange of “throws” (Costello, Carnival in Louisiana 45). These events not only galvanized local pride but also became major tourist attractions that contributed billions to the local economy (McCreadie 11).

The rediscovery of the 1898 Rex parade film, filmed by the American Mutoscope Company and recently recognized by the Library of Congress as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”, illustrates how the legacy of Mardi Gras is both recorded and revered (Pope; Traub). Additionally, the Mardi Gras Act of 1875, which established Mardi Gras as a legal state holiday in Louisiana, institutionalized the celebration and paved the way for its massive economic impact in the modern era (Mardi Gras Act of 1875).

Economic analyses by scholars such as Kevin Fox Gotham reveal that Mardi Gras functions as a “free show” that not only entertains but also stimulates local commerce and tourism (Gotham 188). The festival’s dual role as both a cultural event and an economic engine exemplifies the intricate interplay between tradition and modernity.

Today, Mardi Gras is a global symbol of revelry and cultural fusion. Modern celebrations in New Orleans encompass a vast array of events, from family-friendly parades and masked balls to the edgy subcultures of Mardi Gras Indians and second-line parades. Post-Hurricane Katrina, scholars such as Richard Turner have documented how Mardi Gras became a powerful symbol of communal resilience and renewal in New Orleans (Turner 112). Contemporary studies also note ongoing debates about cultural appropriation and the preservation of authenticity, as local communities seek to protect the sacred traditions of Mardi Gras Indians and other subcultures (Williams 2022; Guss).

Furthermore, academic work has expanded the discussion to include the role of Mardi Gras in forming a transnational carnival identity. Researchers such as Jeroen Dewulf and Nikesha Williams explore how the festival’s African diasporic roots have fostered a unique cultural expression that challenges mainstream narratives of American festivity (Dewulf 2017; Williams 2022). The festival’s ability to adapt to contemporary challenges, from globalization to social media influence, demonstrates its enduring vitality and its capacity to unite diverse communities around shared values of joy, creativity, and resistance.

Mardi Gras stands as a living testament to cultural transformation and resilience. Its history, from the Roman Saturnalia and medieval European feasts to its evolution in colonial Louisiana and its sophisticated modern incarnation, reveals a dynamic process of cultural syncretism that continues to shape regional identity and global carnival culture. New Orleans’ distinctive Carnival, marked by secret societies, elaborate parades, and a complex interplay between tradition and commerce, offers both a celebration of life and a forum for social commentary. As scholars continue to examine its multifarious dimensions, Mardi Gras remains a powerful symbol of the human spirit’s ability to transform adversity into art, resistance, and enduring communal joy.

References:

Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhailovich. Rabelais and His World. Indiana University Press, 1984.

Costello, Brian J. Carnival in Louisiana: Celebrating Mardi Gras from the French Quarter to the Red River. LSU Press, 2017.

Gotham, Kevin Fox. Authentic New Orleans: Tourism, Culture, and Race in the Big Easy. New York University Press, 2007.

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press, 1995.

History.com Editors. Mardi Gras. History.com, A&E Television Networks, 18 Feb. 2025, https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/mardi-gras.

Kinser, Samuel. Carnival American Style: Mardi Gras at New Orleans and Mobile. University of Chicago Press, 1990.

McCreadie, Kane. Rebirth and Revitalization of an Integral Cultural Identity: A History of Mardi Gras Before and After the Civil War. Vulcan Historical Review, vol. 27, 2023, Article 11, https://digitalcommons.library.uab.edu/vulcan/vol27/iss2023/11.

Mitchell, Reid. All on a Mardi Gras Day: Episodes in the History of New Orleans Carnival. Harvard University Press, 1995.

Morris, Toyin Falola, and Matt Childs. The Yoruba Diaspora in the Atlantic World. Indiana University Press, 2005.

Turner, Richard Brent. Jazz Religion, the Second Line, and Black New Orleans. Indiana University Press, 2016.

Van Gennep, Arnold. Manuel de folklore français contemporain (Vol. 1). Picard, 1947.

Williams, Nikesha. Mardi Gras Indians. Louisiana State University Press, 2022.