Marble That Screams

Survey of Western Art I

Hellenistic art, broadly spanning the centuries between Alexander’s death in 323 BCE and the political consolidation of the Mediterranean under Rome by the end of the first century BCE, is often approached through a cluster of intertwined effects: heightened drama, intensified realism, and a new appetite for spectacle. These are not simply stylistic traits or modern labels applied after the fact. They reflect a deeper shift in how images were conceived and used across a connected maritime world of kingdoms, federations, sanctuaries, and commercial hubs. In many Hellenistic contexts, the image behaves less like an isolated object and more like an event, staged through posture, gesture, facial expression, drapery, scale, and architectural placement. The viewer is not only a spectator but a moving presence whose position, pacing, and line of sight are folded into meaning. At the same time, the period’s expanding networks of trade, migration, and cultural exchange encouraged portable imagery and hybrid visual languages that could operate across regions and communities.

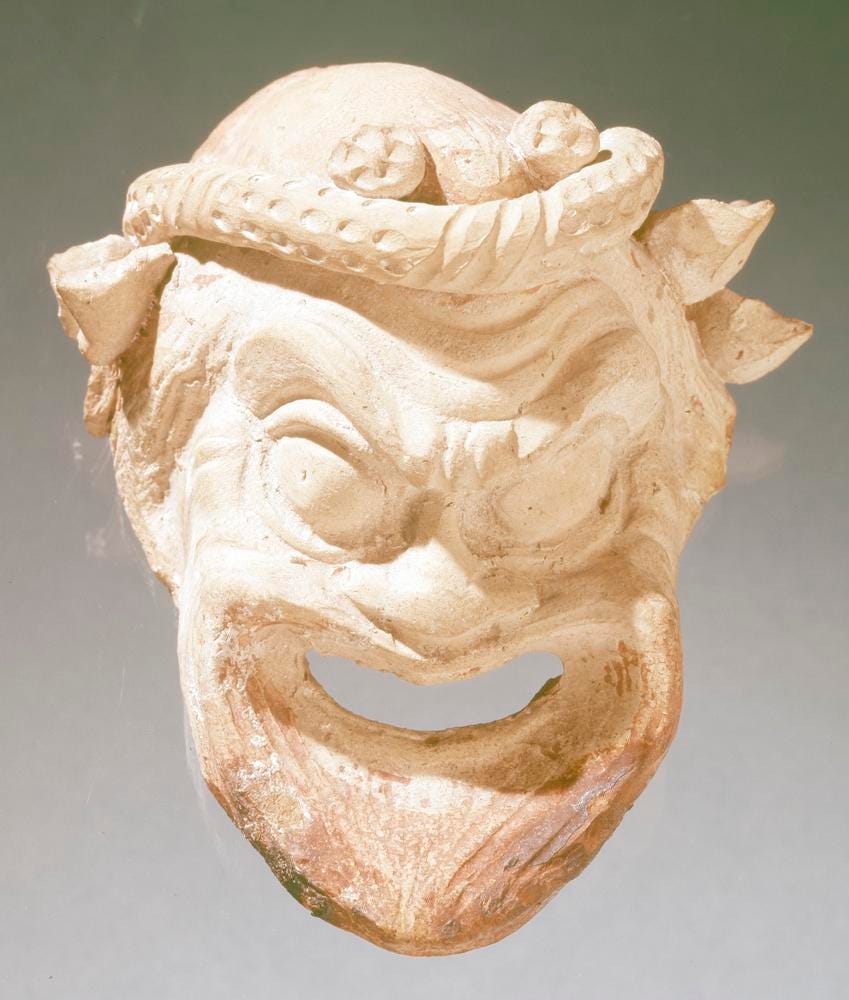

Hellenistic audiences lived within a visual culture trained by performance. Greek theater did not only entertain; it refined habits of reading the body. Masks, stylized expressions, and codified gestures created a grammar in which emotion and identity could be recognized rapidly and at a distance. This grammar circulated beyond the stage through terracotta masks, figurines, and domestic decor, ensuring that theatrical legibility remained available even when no performance was underway. A terracotta comic mask in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, identified as a youth type associated with New Comedy, is materially structured for display, with suspension holes indicating it was meant to hang and be seen as an image in its own right (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Terracotta comic mask). The British Museum’s terracotta mask of an old man from New Comedy amplifies this same principle through deeply furrowed brows, raised eyebrows, and a wide open mouth, all of which function as public signals rather than private psychological subtleties (British Museum, theatre mask). These objects clarify an essential point for sculpture. Much Hellenistic expressiveness is not merely observational naturalism but a cultivated vocabulary shaped by performance conventions that taught viewers how to decode faces and bodies.

Sculpture adopts and adapts this vocabulary in multiple ways. Facial animation, for example, often works through emphatic contrasts: swollen brows, parted lips, tension in the jaw, and an alertness that suggests breath and speech. Gesture similarly becomes a sculptural tool for narrative compression. Hands can become rhetorical, not only anatomical, and torsos twist in ways that resemble stage blocking, positioning the body to communicate its internal state outward. Drapery contributes to this theatrical system as a form of sculptural costume. Cloth in Hellenistic art frequently behaves like a medium of emphasis, turning movement into a visible force through sharply articulated folds, wind-swept diagonals, and layered textures that catch light and sharpen contour. The point is not only virtuosity; it is legibility and affect. Costume-like drapery makes bodies readable as characters and situations, as though marble were staging an action rather than presenting a static ideal.

Small bronzes of performers show this principle with particular clarity because they do not need to disguise their theatrical premise. The Metropolitan Museum’s bronze statuette of a veiled and masked dancer captures motion through the interplay of body, veil, and layered fabric, with the mask underscoring role and transformation as the core of the image (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bronze statuette of a veiled and masked dancer). The dancer is not a portrait; it is a sculptural enactment of performance itself. Theatricality here is not an ornamental theme but a method of organizing form. When Hellenistic sculpture appears to act, it does so because it draws upon a widely shared cultural training in how bodies communicate meaning in public, through conventions honed in the theater and disseminated through objects intended for daily viewing.

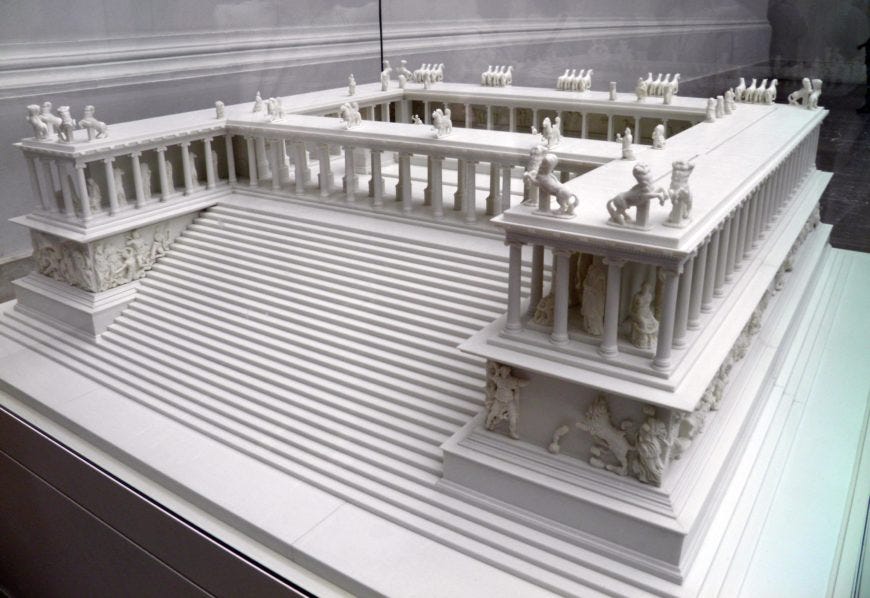

Hellenistic patrons, whether dynastic courts or civic institutions, invested heavily in images that could move viewers at the level of the body. Pathos is therefore inseparable from power, not because every emotional work is crude propaganda, but because affect can bind communities, stabilize authority, and translate ideology into experience. The Great Altar at Pergamon provides a canonical example of emotional intensity deployed as civic persuasion. The Classical Art Research Centre describes the monument as a mid-second-century BCE construction whose sculptural program became central to its later excavation and transport to Berlin, foregrounding the altar’s scale and the prominence of its reliefs as a defining feature (Classical Art Research Centre). The structure’s long Gigantomachy frieze does not merely narrate a myth; it turns conflict into a surrounding field of force. Gods and Giants collide in high relief with bodies that press outward, creating an aesthetic of proximity and pressure. This sensation is crucial; the viewer does not only look at victory but feels its mechanics through the density and violence of the carved encounter. In such contexts, emotional overwhelm is not a byproduct. It is the medium through which a community is invited to experience cosmic order and, by extension, to align itself with the regime and the city that sponsor such a manifestation of divine narrative.

The political work of pathos becomes clearer when placed within broader scholarly accounts of Hellenistic art’s social reach. Pollitt frames the Hellenistic period as heterogeneous and cosmopolitan, shaped by new political and cultural conditions that expanded the repertoire of subjects and styles available to artists and patrons (Pollitt). Stewart likewise emphasizes that Hellenistic art operates across a wide geography and across multiple media, from monumental architecture to gems and luxury arts, a range that makes emotional clarity and legibility especially valuable when images circulate beyond a single locale (Stewart). The Metropolitan Museum’s multi-author volume Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms similarly stresses the international scope of Hellenistic arts and addresses royal self-presentation across coins, gems, sculpture, and other forms, reminding us that the same affective strategies visible at Pergamon also travel through smaller, repeatable objects (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms). Pathos thus becomes one part of an integrated system; monumental spectacle can anchor civic identity, while portable imagery can disseminate a resonant emotional language across networks of patronage, trade, and elite display.

Few formal features announce Hellenistic intensity as sharply as the open mouth, whether it suggests shouting, gasping, exertion, or the strained intake of breath. The open mouth introduces time into sculpture. It implies an unfolding moment rather than an achieved state, and it draws the viewer toward the threshold where marble seems to become flesh. This aesthetic often travels with other signs of physiological extremity; taut neck muscles, compressed torsos, twisted limbs, and faces that resist composure. In later reception history, the Laocoön group became an emblem of this sculptural capacity for extreme expression, and the Vatican Museums’ collection page grounds the group’s identity in antiquarian history as well as ancient testimony, noting its discovery in 1506 and its identification with the Laocoön described by Pliny as a masterpiece of Rhodian sculptors (Vatican Museums). Even when modern chronology and authorship remain debated in scholarship, the group’s force as an exemplar of bodily crisis is undisputed, and its interpretive tradition underscores the same Hellenistic premise; expression is not merely shown but performed through the body’s visible struggle.

At the level of intimate encounter, the bronze Boxer at Rest offers another kind of scream, quieter but equally bodily, expressed through injury and fatigue rather than mythic catastrophe. The Museo Nazionale Romano describes the sculpture’s crude realism and emphasizes the technical use of copper to heighten wounds and blood, a material strategy that intensifies the viewer’s sense of immediacy and vulnerability (Museo Nazionale Romano). The Metropolitan Museum’s long-form feature on the Boxer likewise situates the statue as an ancient masterpiece whose impact depends on the interplay of surface, damage, and implied experience, making the body’s history visible rather than smoothing it into ideal form (Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Boxer). In both cases, the open mouth and battered face do not simply illustrate suffering. They produce an encounter with corporeality as truth-effect, inviting empathy while also risking spectacle. Hellenistic art explores that edge with extraordinary consistency; it repeatedly tests how far the body can be pushed into legibility before it becomes overwhelming, and how overwhelm itself can become meaning.

Hellenistic art often revisits myth with a changed emotional economy. Rather than presenting myth as distant exemplum, it frequently isolates the most charged instant, when consequence becomes visible on the body. This shift can be understood as melodramatic in the strict sense of amplified affect, not as exaggeration for its own sake but as a strategy for making narrative feel present. At Pergamon, the Gigantomachy becomes less a timeless story than a visceral collision staged around the viewer, whose movement alongside the frieze turns narrative into duration. The CARC resource notes the monument’s mid-second-century BCE construction and provides visual materials that underscore its monumental organization, which is essential to how the story is encountered (Classical Art Research Centre). Here, myth is not only read; it is traversed.

This logic extends beyond Pergamon into a wider Hellenistic habit of selecting moments of heightened decision, reversal, or loss. Smith’s survey of Hellenistic sculpture emphasizes how the period’s innovations include new thematic investments in drama, motion, and expressive surfaces that reshape the viewer’s relationship to mythic and human subjects alike (Smith). Ridgway, in her multi-volume work on Hellenistic sculpture, likewise charts stylistic developments that support this broader tendency, showing that what appears as heightened emotion is often tied to changing artistic aims and contexts across regions and centuries (Ridgway). Myth becomes a flexible resource. It can carry dynastic ideology, civic pride, religious experience, or private fascination, but it achieves these ends most powerfully when its emotional core is made visible through bodies that strain, recoil, grasp, or collapse. The result is a Hellenistic narrative mode in which the viewer does not simply recognize a story but experiences the story’s pressure as a sculptural fact.

Hellenistic art repeatedly demonstrates that viewing is not incidental. It is designed. The period’s most ambitious works assume a moving viewer and build meaning through approach, sequence, and shifting vantage. The Great Altar at Pergamon exemplifies this by embedding sculpture into architecture in a way that makes bodily movement essential. The altar’s stairway and surrounding relief demand that the viewer ascend and then continue laterally, encountering the frieze not as a single framed image but as an extended field of action (Classical Art Research Centre). The viewer’s body becomes a measuring instrument for scale and intensity. This is one reason Hellenistic art feels immersive; it anticipates that you will turn your head, adjust your distance, and negotiate the work through time.

3D Model of the Pergamon Altar

Modern digital and institutional projects often confirm, indirectly, this ancient premise. The Staatliche Museen zu Berlin’s page for the 3D model of the Pergamon Altar underscores that the object is now subject to scanning, reconstruction, and new modes of encounter, and it notes the altar hall’s long closure during renovation, which has further encouraged mediated forms of viewing (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin). While the digital model is a contemporary tool, it highlights an ancient reality. The altar is too large and too complex to be reduced to a single glance. Meaning emerges through navigation.

The Nike of Samothrace offers another powerful example of how placement and movement generate meaning. The Louvre’s collection record provides material and technical details, noting the statue’s Parian marble and the ship base in Lartos marble, reminding us that the work’s effect depends on both figure and setting (Musée du Louvre, Victoire de Samothrace). The Louvre’s discussion of the Daru staircase, where the Nike dominates the ascent, further demonstrates how architectural framing can intensify a sense of arrival and climax (Musée du Louvre, A stairway to Victory). Even though the Daru staircase is a modern installation, it resonates with the Hellenistic logic of staged encounter; the figure’s wind-swept drapery and forward drive become more compelling when met through upward movement and widening spatial drama. In Hellenistic terms, the viewer is not outside the work. The viewer is built into its operation.

Hellenistic realism is not best understood as neutral description. It is a crafted surface that produces conviction, a truth-effect designed to make an image feel immediate and credible, even when the subject is mythic or the social meaning is ambiguous. The Old Market Woman in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a Roman marble that preserves a Hellenistic type, is a key case precisely because it complicates simplistic readings of realism as empathy. The museum notes that, despite the figure’s apparent burden and age, her delicate sandals and elaborate drapery suggest she may represent an aged courtesan en route to a festival of Dionysos rather than a peasant vendor (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marble statue of an old woman). Here realism functions as a social code. Age, texture, and bodily strain are legible, but they do not yield a single stable moral interpretation. The image can provoke pity, discomfort, amusement, or judgment, depending on how the viewer reads the figure’s status and situation.

The Boxer at Rest likewise demonstrates realism as persuasion, but in a different register. The Museo Nazionale Romano highlights how injuries are rendered through copper inlays, emphasizing not only the fact of wounds but their visual presence as color and material (Museo Nazionale Romano). The body becomes an archive of experience, and the viewer’s response is guided by that visible accumulation of damage. Pollitt treats the period’s realism as one strand in a broader expansion of artistic aims, including new interests in individuality, emotion, and the depiction of states that earlier Greek art often kept at bay (Pollitt). Stewart similarly presents Hellenistic art as operating in a world of new social and political realities, in which images could no longer rely only on ideal typologies to produce authority; they also mobilized particularity and immediacy (Stewart). Realism, in this sense, is not the opposite of ideology. It is one of ideology’s most effective instruments.

Hellenistic art’s attention to bodies outside classical ideals has long been recognized as one of its defining expansions, but the meaning of that expansion is not self-evident. Images of age, poverty, drunkenness, exhaustion, and injury can invite recognition and compassion, yet they can also turn vulnerability into spectacle. The Old Market Woman type is again instructive because it is poised on this ethical threshold. The Met’s interpretation that she may be an aged courtesan headed to a Dionysiac festival reframes the figure from generic poverty to a socially specific role, implying that the image may operate through irony, social commentary, or ritual association rather than straightforward sympathy (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marble statue of an old woman). The realism remains potent, but its social direction becomes more complex.

The boxer’s battered body presents a different kind of unideal visibility. The statue’s seated posture, damaged face, and materialized blood suggest an aftermath rather than triumph, pushing the viewer toward a contemplation of cost rather than glory (Museo Nazionale Romano; Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Boxer). Yet the very intensity of this visibility can become a form of consumption; the viewer takes in the wounds as aesthetic and emotional evidence. Smith’s overview of Hellenistic sculpture repeatedly returns to the period’s fascination with such bodily states, connecting them to broader cultural interests in character, immediacy, and the depiction of life as lived rather than life as perfected (Smith). Ridgway’s work, attentive to stylistic development and regional variation, further underscores that these body types are not isolated anomalies but part of a sustained exploration of what sculpture can ethically and aesthetically hold (Ridgway). The unideal body in Hellenistic art is therefore not a single message. It is a field of social negotiation, where empathy and hierarchy, intimacy and display, can coexist within the same carved surface.

Hellenistic portraiture, especially in royal contexts, often aims to produce what can be called psychological presence, a sense that the face and body communicate inner life, decision, intensity, or authority. This does not require modern psychological theory; it relies on the same theatrical and realist devices already discussed, redirected toward charisma. The Metropolitan Museum’s Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms volume foregrounds royal self-presentation across media, emphasizing that portrait strategies cannot be isolated from the broader ecosystem of Hellenistic visual culture, where coins, gems, sculpture, and luxury objects reinforce shared messages of legitimacy and power (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms). Charisma becomes a visual effect produced through controlled realism, energetic modeling, and expressive cues that remain legible across regions. In a world where rulers governed diverse populations, a portrait needed to be more than recognizable; it needed to be convincing as an embodiment of authority.

Stewart’s account of Hellenistic art emphasizes how wide-ranging the period’s artistic production was in geography and medium, which makes repeatable images and coherent visual signals especially important for dynastic identity (Stewart). Pollitt similarly situates Hellenistic art within cultural conditions that encouraged new forms of individuality and expressive range, qualities that portraiture could harness to make power appear not only inherited but embodied (Pollitt). The result is not a rejection of idealization but a more flexible toolkit, capable of blending ideal forms with particularizing detail to generate an aura of presence that feels immediate.

Hellenistic realism often resides in surfaces that are meant to be read at close range. Texture becomes a carrier of meaning. Hair can be crisp, turbulent, or softened into shadow. Skin can register age or strain. Fabric can behave like weather. These effects depend on technique and finish as much as on composition. Terracotta figurines, especially those associated with Tanagra, demonstrate how small scale and surface treatment can convey social nuance and charm, and the Met’s essay notes that such figurines were appreciated for naturalistic features, preserved pigments, variety, and market appeal (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tanagra Figurines). The mention of preserved pigment is significant because it reminds us that the ancient sensory field included color, and color can sharpen realism and theatrical legibility alike.

Theatrical masks also preserve the logic of surface as signal. The British Museum’s New Comedy old man mask, with its emphatic facial modeling and open mouth, demonstrates how expression was made readable through exaggeration and surface articulation, often enhanced originally by coatings or pigments even when those do not fully survive (British Museum, theatre mask). The Hellenistic dancer in bronze similarly shows that realism can be produced through the interplay of fabric layers and the contrast between taut and relaxed surfaces, turning material into narrative (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bronze statuette of a veiled and masked dancer). Finish is therefore not decorative. It is structural to meaning, because it shapes how the work catches light, how close the viewer must come, and what kinds of bodily cues become visible.

As Hellenistic networks expanded, images of foreigners and culturally marked figures circulated widely. Such representations could express curiosity and admiration, but they could also crystallize stereotypes and reinforce hierarchies by turning difference into a typology. The significance of this topic is heightened by the period’s international scope, repeatedly emphasized in major overviews. The Met’s Hellenistic volume frames the arts of the period as operating across kingdoms and regions and across many media, which necessarily means that images moved among communities with different expectations and power relations (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms). In such a context, the depiction of cultural difference is never neutral. It participates in how the Hellenistic world imagines itself as connected while remaining unequal. Smith’s synthesis and Stewart’s broader narrative both support the premise that Hellenistic art’s heightened interest in character and specificity can be directed toward the human variety produced by empire and mobility, with representation functioning as both recognition and control (Smith; Stewart). When realism is applied to ethnographic types, it can dignify by granting attention, but it can also fix identity into consumable forms, making the politics of looking inseparable from the politics of power.

Hellenistic spectacle is not confined to single works; it is built into urban and sacred environments that stage public experience. Terraced sanctuaries, acropoleis, and processional routes organize movement, frame views, and intensify arrival. Pergamon’s altar is not simply placed; it is embedded within a citadel landscape where approach and elevation intensify its monumental and emotional effects. The CARC resource emphasizes the altar’s prominence and unusual character, providing a clear institutional overview that anchors the monument’s date and excavation history (Classical Art Research Centre). Once recognized as an architectural and sculptural system rather than a freestanding object, the altar’s frieze becomes a device for turning civic space into a theatrical field.

The Nike of Samothrace similarly embodies spectacle, not only through its dramatic drapery and implied wind, but through its relationship to a ship base and its association with victory as a public claim. The Louvre’s collection record foregrounds the work’s materials and construction as a composite arrangement of figure and base, reinforcing the idea that meaning emerges from the assembled environment (Musée du Louvre, Victoire de Samothrace). The Louvre’s account of the Daru staircase demonstrates how monumental placement can generate a ritualized ascent toward a climactic image, echoing ancient strategies of choreographed encounter even when the setting is modern (Musée du Louvre, A stairway to Victory). Spectacle in the Hellenistic Mediterranean is therefore a spatial practice. It is an art of routes, thresholds, and orchestrated visibility.

Monumentality escalates in cultures where fame, prestige, and perceived power are commodities. Hellenistic centers competed for attention through ambitious building programs and sculptural commissions that could draw visitors, secure divine favor, and advertise resources. The Great Altar at Pergamon is frequently approached through its sculptural intensity, but its very existence also implies a competitive landscape of sanctuaries and cities investing in large-scale visual rhetoric. The Met’s publication Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World situates Pergamon within a broader geopolitical and cultural framework, reinforcing that its artistic production belongs to a wider phenomenon of Hellenistic monumental ambition (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms). Monumentality, in this sense, is not only an aesthetic preference. It is a public language of capacity. It announces that a city or dynasty can command materials, labor, technical expertise, and symbolic capital.

This dynamic also intersects with the period’s mobility. As objects and people moved, reputations moved with them. Cities and sanctuaries became destinations, and spectacular monuments functioned as proof of significance in a crowded Mediterranean world. The effect is circular. Prestige attracts visitors and patrons, which in turn supports further monumental display. Hellenistic spectacle becomes one of the engines that drive cultural centrality.

Hellenistic artists and patrons repeatedly exploit sensory factors that make sculpture and architecture feel alive. Drapery becomes wind. Surfaces become skin. Relief becomes pressure. Although many ancient settings are fragmentary, the surviving works still reveal a consistent aim; to translate forces like motion and atmosphere into form. The Nike of Samothrace is the most famous example of drapery turned into meteorology, with cloth clinging and billowing as if the air itself were sculpted. The Louvre’s technical notes, emphasizing the materials and the constructed nature of the statue and base, remind us that this effect is engineered, built from multiple parts to produce a unified sensory impression (Musée du Louvre, Victoire de Samothrace). The boxer’s copper-inlaid wounds similarly show that realism can be sensory as well as visual, with color and material used to trigger bodily recognition (Museo Nazionale Romano). These works embody a Hellenistic desire to animate stone and bronze, not by literal movement, but by giving the viewer the feeling of movement through form, texture, and implied force.

The Hellenistic Mediterranean was bound together by sea routes linking ports, markets, sanctuaries, and royal centers. This connectivity shaped style and subject matter, encouraging visual languages that could travel and hybrid forms that could address diverse communities. One of the clearest examples is the god Serapis, whose image was crafted to operate across Egyptian and Greek cultural frameworks. The Met’s intaglio with the head of Serapis explains that Serapis combined Osiris and Apis and, under the Ptolemies, acquired a Greek appearance and characteristics associated with Zeus and Hades, making the deity visually legible within a Greek-inflected iconographic system (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Intaglio with head of Serapis). The object’s portability matters here. A carnelian gem is not monumental propaganda, but it participates in the same cross-cultural project, compressing a political and religious synthesis into a form that can circulate.

Mobility also shaped production through trade and consumer demand. Brian Martens’s American Journal of Archaeology study of Delos identifies a group of marble statuettes of Aphrodite likely carved on Delos in the late second and first centuries BCE and ties them to intensifying demand among private consumers, demonstrating how the production of classical-looking marble forms responded to market conditions within the eastern Mediterranean rather than being reducible to Italy-centered narratives (Martens). Delos, as a node in the art trade, exemplifies globalization at the level of workshop practice and distribution, where style becomes both a cultural inheritance and a commodity calibrated to buyers.

The Met’s Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms volume reinforces the broader framework for these phenomena by emphasizing the international scope of Hellenistic arts and examining how iconography and style operate across media including gems, sculpture, mosaics, and vessels (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms). Globalization here is not a vague metaphor. It is visible in how images are designed to move, how forms are adapted to new contexts, and how cultural mixing becomes a deliberate aesthetic resource.

Hellenistic visual systems also permeated daily life. The theatrical grammar of bodies and the persuasive surface of realism appear not only in civic monuments but in domestic and personal objects that shaped private experience. Tanagra figurines, widely circulated and prized for their naturalistic charm and traces of pigment, exemplify how small-scale terracottas could bring fashionable bodies, social nuance, and a sense of lived presence into homes and tombs (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tanagra Figurines). These figurines are often quiet in tone, but their naturalism participates in the same cultural shift toward immediacy and character.

Portable cult objects similarly register mobility and mixed communities. A Serapis gem, for example, could support devotion within a world where individuals and families moved across regions, carrying images that anchored identity and practice in portable form (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Intaglio with head of Serapis). Theatrical masks and performer bronzes, too, bring entertainment culture into the realm of possession and display, suggesting that the pleasures and legibilities of performance could be collected and re-encountered visually (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bronze statuette of a veiled and masked dancer; British Museum, theatre mask). Even where the tone is playful or decorative, these objects participate in the larger Hellenistic project of making the body readable and socially meaningful through form.

One of the most consequential aspects of Hellenistic globalization is the portability of what later cultures call Greek art. Hellenistic workshops and consumers operated within a world where earlier forms could be reactivated, adapted, and circulated. Martens’s study of Delos speaks directly to this phenomenon through the production of classical-looking statuettes for private consumers, showing how style could be calibrated to desire and demand within a trade network (Martens). The process is not merely replication; it is a negotiation between recognizable visual authority and contemporary taste.

This helps explain why Hellenistic art repeatedly oscillates between ideal and unideal bodies, between timeless gods and intensely particular humans. The period does not abandon the prestige of classical form; it multiplies the available registers, treating style itself as a repertoire that can be deployed for different audiences and contexts. The Met’s Hellenistic volumes underscore this multiplicity by addressing a wide range of media and contexts, from royal self-presentation to luxury arts and domestic objects, all within an international frame (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms; Metropolitan Museum of Art, Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms). Greekness becomes both cultural inheritance and portable prestige, capable of being staged as spectacle, worn as identity, or condensed into a gem.

Hellenistic art is often summarized as an age of drama and realism, yet the deeper transformation lies in how images were engineered to function within a connected Mediterranean world. Theater supplied a public grammar of legibility, teaching viewers to read masks, expressions, gestures, and costume-like drapery as signals of identity and feeling. Sculpture absorbed this grammar, turning bodies into performers that appear to breathe, recoil, strain, and act. Realism, far from being a neutral mirror of life, operated as a truth-effect that could persuade, unsettle, or compel empathy, whether in the bruised immediacy of the Boxer at Rest or the socially ambiguous specificity of the Old Market Woman. Spectacle expanded these strategies into civic space, with monuments like the Great Altar at Pergamon staging emotion as a collective encounter and works like the Nike of Samothrace embodying motion and victory through choreographed placement and sensory force. Across all of these examples, mobility and cultural mixing are not background conditions but active drivers, shaping portable imagery, hybrid deities like Serapis, and market-responsive production visible in hubs such as Delos. Hellenistic art, then, is not simply more emotional than what came before. It is more systemic in its handling of the viewer, more flexible in its use of style as a repertoire, and more attuned to the realities of a world in which images moved, meanings shifted, and power increasingly relied on the capacity to make itself felt.

References:

British Museum. theatre mask. The British Museum Collection Online, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1842-0728-750.

Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford. The Great Altar at Pergamon. CARC Resources, https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/carc/resources/Sculpture/Sites/pergamon.

Martens, Brian. Delos and the Late Hellenistic Art Trade: Archaeological Directions. American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 125, no. 4, 2021, https://ajaonline.org/article/4379/. DOI:10.3764/aja.125.4.0535. A version of record is also available via University of Chicago Press Journals, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.3764/aja.125.4.0535.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Art of the Hellenistic Kingdoms: From Pergamon to Rome. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022, https://resources.metmuseum.org/resources/metpublications/pdf/Art_of_the_Hellenistic_Kingdoms_From_Pergamon_to_Rome.pdf.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Bronze statuette of a veiled and masked dancer. The Met Collection, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/255408.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Intaglio with head of Serapis. The Met Collection, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/551341.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Marble statue of an old woman. The Met Collection, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248132.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://resources.metmuseum.org/resources/metpublications/pdf/Pergamon_and_the_Hellenistic_Kingdoms_of_the_Ancient_World.pdf.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Tanagra Figurines. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/tanagra-figurines.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Terracotta comic mask. The Met Collection, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/241076.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Boxer: An Ancient Masterpiece Comes to the Met. The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/the-boxer.

Museo Nazionale Romano. Il Pugilatore in riposo torna a Palazzo Massimo. Museo Nazionale Romano, https://museonazionaleromano.beniculturali.it/2023/12/il-pugilatore-in-riposo-torna-a-palazzo-massimo/.

Musée du Louvre. A stairway to Victory – The Daru staircase. Louvre, https://www.louvre.fr/en/explore/the-palace/a-stairway-to-victory.

Musée du Louvre. Victoire de Samothrace. Collections du Louvre, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010252531.

Pollitt, J. J. Art in the Hellenistic Age. Cambridge University Press, 1986. A bibliographic record is available via Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/artinhellenistic0000poll.

Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo. Hellenistic Sculpture. University of Wisconsin Press. A bibliographic record is available via Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/hellenisticsculp0002ridg.

Smith, R. R. R. Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook. Thames & Hudson, 1991. Publisher page, https://www.thamesandhudson.com/products/hellenistic-sculpture-world-of-art.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung. 3D-Modell des Pergamonaltars. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, https://www.smb.museum/museen-einrichtungen/antikensammlung/sammeln-forschen/3d-modell-des-pergamonaltars/.

Stewart, Andrew. Art in the Hellenistic World: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press, 2014. Cambridge Core, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/art-in-the-hellenistic-world/3E109268A6294B7939130524A3D137BD.

Vatican Museums. Laocoön. Musei Vaticani, https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-pio-clementino/Cortile-Ottagono/laocoonte.html.