Mapping the Boundaries: Black Artists, Cultural Identity, and the Politics of Appropriation

The debate surrounding cultural appropriation in the visual arts has grown increasingly urgent in our globalized, interconnected world. Cultural appropriation, defined as the adoption or use of elements from one culture, often by members of a dominant or privileged group, without proper recognition or sensitivity to their significance, has long been a subject of contention. In the realm of visual arts, this debate is particularly charged when it involves Black cultural expressions. Non-Black artists have often profited from borrowing aesthetic elements rooted in Black history, while Black artists themselves confront both historical erasure and the commodification of their cultural symbols.

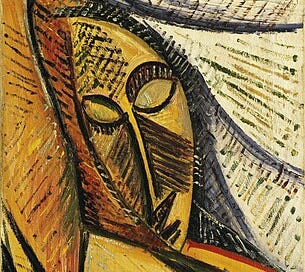

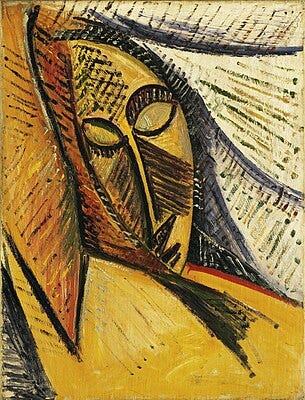

The roots of cultural appropriation in art extend deep into modern art history. Early 20th-century European modernists such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse famously incorporated African masks and sculptures into their work. However, as Roy Sieber explains in African Art in the Cycle of Life, these appropriations often reduced the rich symbolic traditions of African art to mere aesthetic devices; exoticized objects that reinforced colonial hierarchies (Sieber 45). Similarly, Manthia Diawara documents in Black Cultural Traffic how white artists in mid-20th-century America appropriated elements of African American music and culture, often stripping them of their sociopolitical contexts (Diawara 102). Moreover, appropriation extended beyond African art; Native American headdresses and indigenous patterns were frequently co-opted by non-indigenous designers, commodifying sacred symbols for commercial purposes. James O. Young, in Cultural Appropriation and the Arts, argues that such practices not only distort the original meanings of cultural artifacts but also contribute to the systematic exclusion of marginalized communities from the economic benefits of their own heritage (Young 67). These historical patterns underscore that cultural appropriation in art is not simply about visual borrowing; it is intertwined with the legacy of colonial exploitation and ongoing power dynamics.

In today’s art world, cultural appropriation has taken on new dimensions as images and styles circulate globally at unprecedented speeds. One high-profile controversy involved white artist Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, a painting depicting Emmett Till that sparked widespread outrage. Critics, including prominent voices in The New York Times, argued that by portraying Black trauma through an aestheticized lens, the work reduced deeply personal historical suffering to a provocative spectacle (Mitter 3). Mainstream fashion has also been a battleground for debates on cultural appropriation. Non-Black designers have repeatedly incorporated Afrocentric motifs, such as kente cloth patterns and cornrows, into their collections without acknowledging their origins or providing economic benefits to Black artisans. Elizabeth Tunstall’s Decolonizing Design: Towards a Cultural Justice Movement offers numerous case studies where such appropriation not only dilutes cultural significance but also reinforces inequities (Tunstall 89). These modern examples illustrate that the debate is not solely about aesthetics but is fundamentally linked to issues of economic justice, historical recognition, and power.

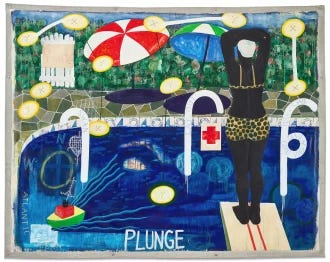

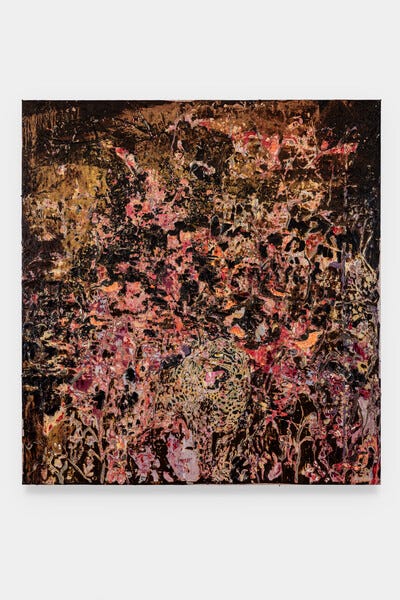

For Black artists, engaging with cultural traditions is often an act of reclamation and empowerment. Drawing from African, Caribbean, and Indigenous sources, Black creators work to recontextualize their cultural heritage and assert their own narratives. Kerry James Marshall, for example, uses figurative painting to re-inscribe Black bodies into art history; a history that has long marginalized or misrepresented them (Gioni 110). Similarly, Kehinde Wiley reinterprets classical European portraiture by centering Black subjects, thereby challenging historical norms that rendered Black individuals invisible or stereotyped. Mark Bradford provides another compelling example: by using found materials sourced from urban environments, such as billboard remnants and commercial paper, Bradford creates layered compositions that reflect the lived realities of his community. Miwon Kwon explains in One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity that Bradford’s technique captures multiple narratives embedded in urban spaces, narratives often ignored by mainstream culture (Kwon 58). Kara Walker’s silhouette installations, which reference racist imagery from 19th-century minstrelsy, serve as a powerful critique that forces audiences to confront the violent legacies of cultural exploitation (Foster 75). These examples illustrate that ethical cultural exchange involves a deep engagement with context, history, and community; a process that distinguishes genuine cultural appreciation from exploitative appropriation.

Black artists employ several strategies to navigate the fine line between cultural appreciation and exploitation. One key strategy is contextualization and reclamation; by embedding historical context into their work, Black artists reclaim cultural symbols and redefine their meanings. For instance, Kerry James Marshall’s paintings include visual references to African art and Black history, re-situating these elements within narratives of resilience and pride (Gioni 115). Another approach is community engagement and collaboration. Many Black artists work directly with their communities to ensure that cultural symbols are used authentically and respectfully. Theaster Gates, whose projects often blend art with urban regeneration, has worked extensively to revitalize historically Black neighborhoods, using art as a tool for community empowerment (Thompson 82). Economic redistribution and institutional critique also play crucial roles; initiatives such as Hank Willis Thomas’s For Freedoms challenge museums and galleries to address historical inequities by redistributing resources and increasing representation of Black artists (Rosen 116). Finally, some artists, such as Simone Leigh, who represented the U.S. at the Venice Biennale, interrogate power structures directly by foregrounding Black feminist narratives and demanding accountability from institutions that have marginalized these voices (Enwezor 94). These strategies reveal that ethical cultural exchange is deeply interwoven with questions of identity, community, and power.

The conversation surrounding cultural appropriation in the visual arts has far-reaching implications for how art is produced, critiqued, and valued. Black artists’ efforts to negotiate cultural boundaries have not only reshaped artistic practices but also influenced broader cultural conversations about equity and representation. As Art21 notes, Bradford’s transformation of found materials into layered social narratives is emblematic of a larger shift in how marginalized voices reclaim their histories through art (Art21). Major institutions such as the Whitney Museum, Tate, MoMA, and the Guggenheim have begun to re-evaluate their collections and exhibition practices in light of these critiques, part of a broader effort to address the historical erasure of Black cultural contributions and foster more inclusive narratives. The legacy of Black artists who navigate cultural appropriation ethically is evident in the increased visibility of Black artistic voices and in ongoing efforts to redistribute economic and institutional power within the art world (Young 67; Tunstall 89). Moreover, the impact of these practices extends beyond art. They offer critical models for cultural exchange that emphasize respect, accountability, and community engagement; principles increasingly relevant in discussions about social justice and decolonization.

The ongoing conversation about cultural appropriation in the visual arts reveals the complexities of power, representation, and historical memory. While non-Black artists have often profited from Black cultural expressions without acknowledgment, Black artists navigate these treacherous waters with a heightened sense of responsibility and ethical commitment. By contextualizing their influences, engaging directly with their communities, and challenging institutional practices, Black artists redefine the boundaries between cultural appreciation and exploitation. Their strategies ensure that cultural heritage is respected and provide a roadmap for a more inclusive and equitable art world. As this dialogue continues to evolve, the work and legacy of Black artists stand as a powerful testament to the transformative potential of ethical cultural exchange.

References:

Diawara, Manthia. Black Cultural Traffic: Crossroads in Global Performance and Popular Culture. University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Enwezor, Okwui. The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945-1994. Prestel Publishing, 2001.

Foster, Hal. Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency. Verso Books, 2015.

Gioni, Massimiliano, editor. Kerry James Marshall: Mastry. Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 2016.

Kwon, Miwon. One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. MIT Press, 2004.

Mitter, Siddhartha. The Problem with Dana Schutz’s Painting of Emmett Till. The New York Times, 23 Mar. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/03/23/arts/design/dana-schutz-open-casket-emmett-till.html. Accessed 13 Jan. 2025.

Rosen, Rebecca. Art and Activism in the 21st Century. Duke University Press, 2018.

Steinhauer, Jill. “Mark Bradford and the Urban Landscape.” The New York Times, 15 May 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/05/15/arts/design/mark-bradford-and-the-urban-landscape.html. Accessed 13 Jan. 2025.

Thompson, Krista. Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice. Duke University Press, 2015.

Tunstall, Elizabeth. Decolonizing Design: Towards a Cultural Justice Movement. MIT Press, 2019.

Young, James O. Cultural Appropriation and the Arts. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Gopinath, Gayatri. “Refusal of Use: Art, Culture, and the Politics of Appropriation.” October, vol. 165, 2010, pp. 33–52.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. South End Press, 1992.