Between 1551 and 1589, King Henri III of France steered his realm through dynastic upheaval, religious civil wars, and an audacious court culture that earned him a reputation as one of early modern Europe’s most controversial, and in hindsight proto-queer, rulers. Born Alexandre-Édouard de Valois at Fontainebleau on September 19, 1551, he was steeped in humanist learning from the outset. Under the tutelage of Nicolas Bourbon, whose lectures on Cicero and Seneca instilled classical gravitas, and the court master François de La Mothe-Fénelon, who trained him in rhetoric, dance, and ceremony, Henri was performing in ballets de cour by age five, rituals whose stylized movements would later inform the lavish fêtes of his reign (Knecht 15).

As the fourth son of Henri II and Catherine de’ Medici, Henri belonged to the Valois-Angoulême branch that had ruled France since 1515. His mother’s Tuscan lineage introduced Italianate fashions and spectacles, sumptuous pageantry and intricate costumes, that enriched courtly life yet aroused suspicion among conservative nobles wary of “foreign” excess (Knecht 23–25). From birth styled duc d’Angoulême, he became duc d’Orléans in 1566, governing the Île-de-France, and duc d’Anjou in 1567, establishing his chancellery at Blois and securing the revenues that would underwrite his later patronage of artists and perfumers (Wikipedia contributors, “Duke of Anjou”).

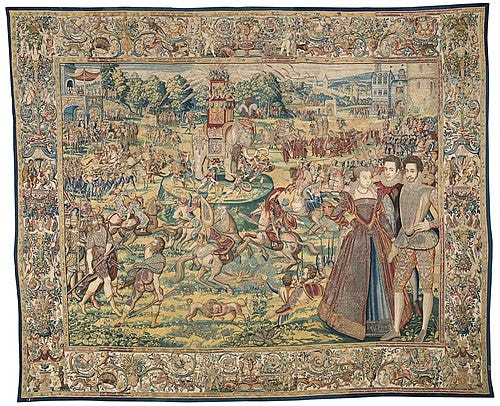

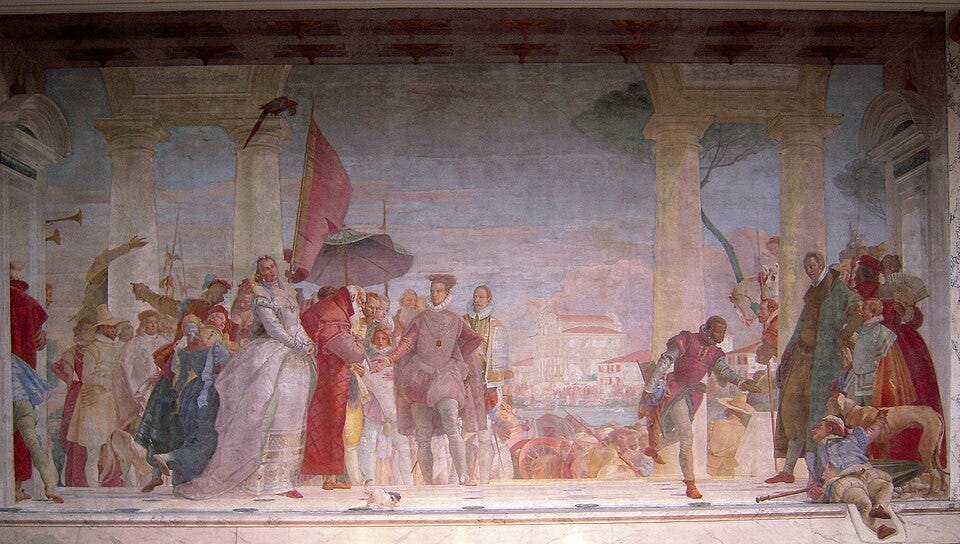

Catherine de’ Medici’s political acumen shaped every stage of his career. She orchestrated his marriage to Louise of Lorraine, mediated disputes with the powerful Guise faction, and in their correspondence urged him to channel his flair for the spectacular into demonstrations of regal majesty rather than personal vanity (Salazar 216–17). Yet it was beyond France’s borders that Henri first tasted sovereignty: elected King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in May 1573, he agreed to the Henrician Articles; Europe’s first written constitutional pact guaranteeing noble election of the monarch, religious toleration, and parliamentary consent for taxation and war. His arrival in Kraków in February 1574, celebrated with triumphal arches and Italianate pageants, foreshadowed the theatrical court he would import home (Wikipedia contributors, “Henry III of France”; Łojek 112).

The sudden death of Charles IX in May 1574 prompted Henri’s secret departure from Poland. After slipping through German territories to avoid Habsburg entanglements, he reached Lyon and then proceeded to Reims, where on February 13, 1575, he received the traditional anointing and crown. Observers marveled at his silver-embroidered velvet robes and lace cuffs; garments so richly ornamented they seemed almost feminine, inaugurating the king’s lifelong reputation for sartorial daring (Wikipedia contributors, “Henry III of France”).

Henri’s accession coincided with the French Wars of Religion (1562–98), a protracted struggle between Catholics and Huguenots. Preferring moderation, he vacillated between conciliatory edicts, mirroring his Polish experience, and forceful campaigns against the Guise-led Catholic League, a balancing act that undermined his authority (Knecht 78–82). When Protestant forces rose in arms, he issued the Edict of Beaulieu on May 6, 1576, granting Huguenots freedom of worship outside Paris, assembly in fortified towns, and access to public office. The decree, however, prompted Catholic nobles to form the League and rapidly plunged France back into open warfare (Wikipedia contributors, “Edict of Beaulieu”).

By 1583 the crown’s debt had swollen to unsustainable levels. In response, Henri and Chancellor Birague introduced a new salt tax (gabelle), doubled the taille in key provinces, sold judicial offices at premium prices, and imposed austerity on the extravagant court. These fiscal measures raised over three million livres annually, stabilizing royal finances and funding campaigns against League strongholds (Collins 143–45).

The conflict climaxed in the War of the Three Henrys (1585–89), pitting Henri III against Henry of Guise (Catholic League) and Henry of Navarre (Huguenot heir). Following Navarre’s victory at Coutras in 1587 and the hard-line Treaty of Nemours in 1585, Henri attempted to outmaneuver both rivals. His gambit reached its grisly apex on December 23, 1588, when he lured the Duke of Guise to Blois under false pretenses and had him assassinated in the château’s council chamber. Although justified as necessary to preserve royal prerogative, the act shocked Catholic Europe and led to Henri’s excommunication by the League-dominated Parlement of Paris (Wikipedia contributors, “Henry I, Duke of Guise”).

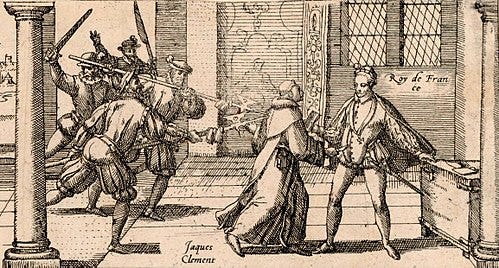

Just months later, on August 1, 1589, a fanatical Dominican novice named Jacques Clément gained access to Saint-Cloud under the guise of a secret message. During Mass he fatally stabbed the king, who died the next morning after naming Navarre his heir and uttering the haunting words, “O Lord, have mercy on me; make me worthy of the crown of martyrdom” (Wikipedia contributors, “Henry III of France”). His assassination extinguished the Valois line and ushered in the Bourbon dynasty.

Henri’s personal life mirrored his political turbulence. His 1575 marriage to Louise of Lorraine, grounded in genuine affection, produced no children; after his death, Louise donned black for the rest of her life, embodying the austere piety she brought to the role of queen consort (Knecht 121). Meanwhile, Henri’s court became famed, and notorious, for its avant-garde fashions: pastel doublets slashed to reveal brocaded linings, Venetian lace collars, scented gloves, powdered wigs, and rouged cheeks. Moralists decried these “theatrical effeminacies,” but modern scholars interpret them as deliberate performances of royal magnificence and a subversion of rigid gender norms (L’Estoile 2:242; Senelick).

Central to this performative court were les mignons, Henri’s intimate circle of favorites, figures such as the duc d’Épernon, who exchanged perfumed gloves, love-tokens, and poetry, and openly wept at royal rebuke. Pamphleteers seized upon their intimacy to allege erotic rituals, weaponizing rumors of homosexuality as political smears despite the absence of direct evidence (Crawford 517). Clerical tracts like Nicolas Caussin’s La Vieillesse d’Hercule (1589) satirized the king’s masque cross-dressing, Henri and his companions in women’s gowns, as pagan inversion, while League propagandists distributed woodcuts of the sovereign in skirts alongside martial images of Guise to cast his gender play as a national threat (Senelick; Collins 149).

Today, historians eschew anachronistic labels such as “gay,” instead framing Henri III’s court as an early modern theater of gender performance. As the Michigan State University dissertation The One Thousand Faces of the Last Valois King, Henri III argues, his sartorial and behavioral experiments prefigure contemporary queer theories of performativity (MSU Thesis 22–24). François Clouet’s circa 1578 miniature, pearls at his ruff, rouge on his cheeks, now in the Harvard Art Museums, underscores his aesthetic daring and has featured prominently in exhibitions on queer early modernity. Contemporary drag-king performers cite his court as an antecedent of gender play, and scholarly symposia such as the École des Chartes’ 2018 “Queer Courts” conference celebrate his proto-drag legacy (Harvard Art Museums; Salazar 218).

King Henri III’s reign fused dynastic duty, religious conflict, and avant-garde gender expression into a singular courtly spectacle that both stabilized and scandalized France. His deliberate performance of effeminate style and cultivation of les mignons provoked moral panic in his own time and inspires reclamation today. By tracing his life through political, religious, and cultural lenses, we recognize Henri III not merely as a failed monarch but as a pivotal figure in the longue durée of LGBTQ history.

References:

Collins, James B. Fiscal Reform and the Crown in France, 1575–1590. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Crawford, Katherine B. Love, Sodomy, and Scandal: Controlling the Sexual Reputation of Henry III. Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 12, no. 4, Oct. 2003, pp. 513–42.

Knecht, Robert J. The Valois: Kings of France 1328–1589. Hambledon Continuum, 2007.

L’Estoile, Pierre de. Registre-Journal du Règne d’Henri III, vol. 2: 1579–81. Edited by Madeleine Lazard and Gilbert Schrenck, Droz, 2000.

Łojek, Stanisław. The Henrician Articles: Constitutional Basis of the Polish Monarchy. Historical Review, vol. 8, no. 2, 1995, pp. 109–27.

MSU Thesis. The One Thousand Faces of the Last Valois King, Henri III: Gender Nonconformity and Court Culture. Michigan State University, 2010.

Salazar, Philippe Joseph. Henri III de Valois. Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History, edited by Ulf Lindqvist et al., Routledge, 2012, pp. 214–19.

Senelick, Laurence. Henry III’s Court as a Proto-Queer Space. The Gay & Lesbian Review, May–June 2019.

Wikipedia contributors. Duke of Anjou. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, 3 March 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_of_Anjou.

Wikipedia contributors. Edict of Beaulieu. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, 3 March 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edict_of_Beaulieu.

Wikipedia contributors. Henry I, Duke of Guise. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, 3 Mar. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_I,_Duke_of_Guise.

Wikipedia contributors. Henry III of France. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, 3 March 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_III_of_France.

Harvard Art Museums. Henry III (1551–1589), King of France. Style of François Clouet, c. 1578, vellum on wood, 58 × 44 mm. Museum Collection, Harvard Art Museums.

Having immersed myself in the fantastic mini series “Versailles” I am immediately drawn to the parallels of court intrigue and dramatic costume, particularly surrounding the fate of the Valois name and St. Cloud, later inherited by Philippe duc d’Orleans / duc d’Anjou, brother to Louis XIV. For anyone who has watched the series, you will know Alexander Vlahos’ portrayal of Philippe is not only spectacular, but one could see him easily playing Henry III as progenitor of such court practices.

Fabulous read, capturing the imagery and enticing me to read more on this ‘failed king’ whose imprint remained ever after on the trends of the French court.