Robert Mapplethorpe’s emergence as a visual artist coincided with a pivotal shift in American queer life. The Stonewall Riots of 1969 ignited a new wave of activism, transforming LGBTQ identities from private and closeted to political and public. Into this turbulent cultural moment stepped Mapplethorpe, a young gay man from conservative Queens, New York, who would challenge nearly every boundary governing eroticism, race, gender, and high art. Unlike other queer artists of the era, David Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar, and Nan Goldin, whose works leaned toward diaristic or documentary modes, Mapplethorpe’s style was cool, formal, and impeccably staged.

Mapplethorpe’s art not only reflected his own identity but intervened in debates about what was permissible to show, who had the right to be seen, and how beauty itself could become a weapon of queer assertion. As Jennifer Blessing notes, “Mapplethorpe harnessed beauty with the precision of a classicist and the rage of a provocateur” (Blessing 7).

Content Warning:

The following discusses explicit homoerotic imagery (full-frontal nudity, sadomasochism), racialized eroticism, and uses strong sexual language. It also addresses censorship controversies and AIDS-related themes. Readers sensitive to these topics should proceed with caution.

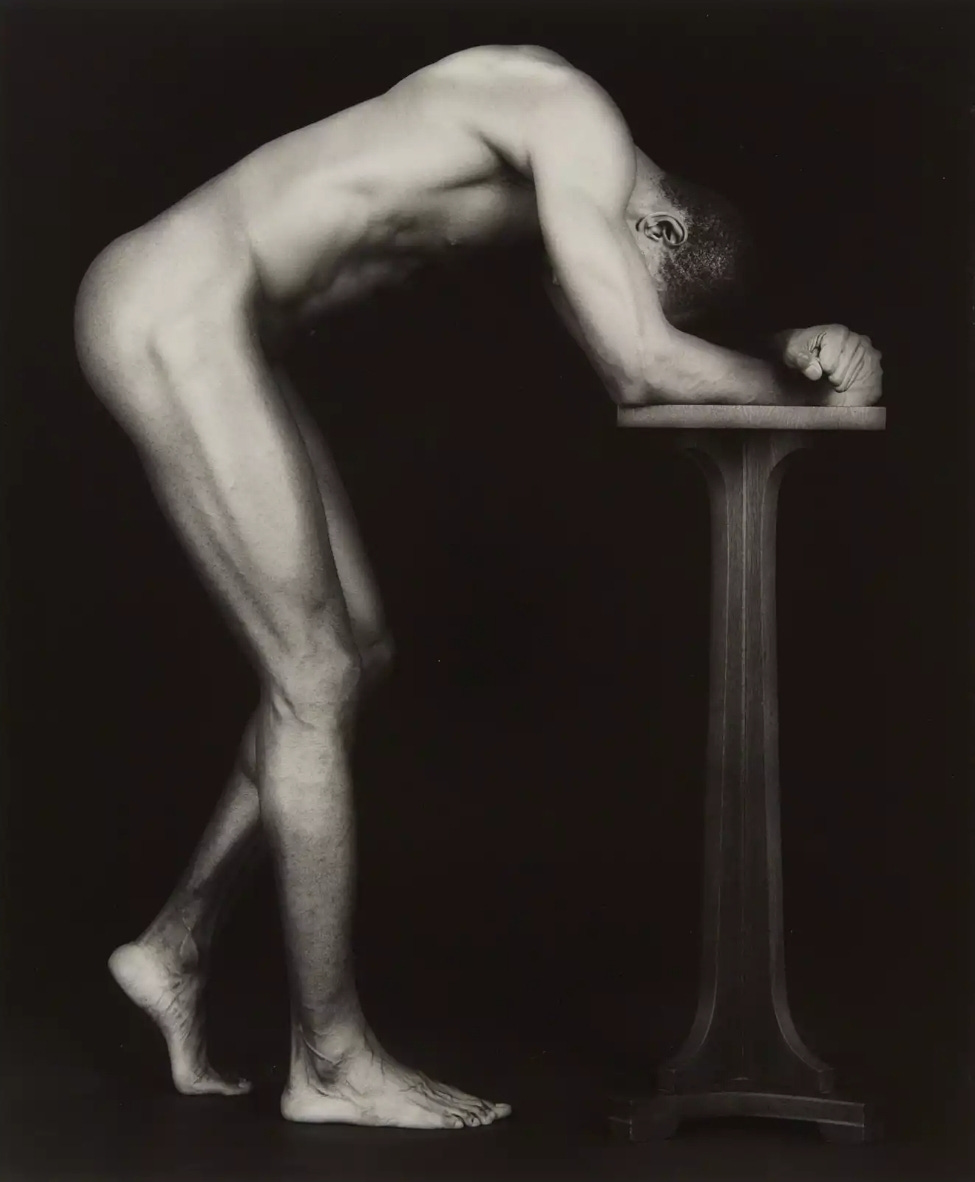

Mapplethorpe’s early training as a sculptor at Pratt Institute significantly shaped his photographic sensibility. His subjects, whether nude men, women, or flowers, are treated as volumes to be lit, carved, and elevated. The compositional rigor he brought to portraiture evoked the precision of Renaissance painters like Bronzino or Piero della Francesca. In Ajitto (1981), a Black male model is seated on a pedestal, nude, his limbs drawn inward in a compact pose that mimics classical sculpture. The platinum print captures subtle tonal shifts on his skin, rendering the body as both divine and erotic. Art historian Kobena Mercer argues that “images like Ajitto are aesthetically disciplined acts of repair,” where Mapplethorpe attempts to “reclassify” the Black body from object of exoticism to subject of admiration (Mercer 179). Yet Mercer also warns that “aesthetic transcendence may mask, rather than undo, the structure of fetishistic looking” (Mercer 177).

Mapplethorpe once remarked, “I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before. The object can be male or female. It can be flowers or it can be cocks. It’s not important” (qtd. in Morrisroe 152). In other words, the subject mattered less than the perfection of its form; though that very indifference is what made his images so politically charged.

His sculptural training carried over into his portraits of cultural figures. In Patti Smith (1975), later used as the cover for her album Horses, Smith is shown in a crisp white shirt, black jacket slung over her shoulder, against a minimalist wall. Mapplethorpe’s framing emphasizes her androgyny and intellectual poise, recalling classical busts in its clarity and restraint. As Richard Meyer observes, Mapplethorpe’s “aesthetic of discipline” meant that “every fold of cloth, every gradation of light, is intentional” (Meyer 118). Smith herself recalled, “Robert was seeking to refine his work, to reconcile the sacred and the profane, and I had become his work of art” (Smith 142).

Similarly, in Philip Glass and Robert Wilson (1976), Mapplethorpe captures two avant-garde icons in still formality: both men seated side by side, dressed in dark clothing, their faces stoic. The plain backdrop eliminates narrative, inviting us to see them as sculptural presences unified by symmetry and chiaroscuro lighting. This portrait, like his erotic work, transforms bodies into timeless forms; iconic representations of modernist rigor (Getty Museum “Philip Glass and Robert Wilson”).

Through these examples, Mapplethorpe’s early “classical eye” emerges: a commitment to formality, balance, and compositional perfection, whether photographing marble-like flesh or the subtle musculature of a famous face.

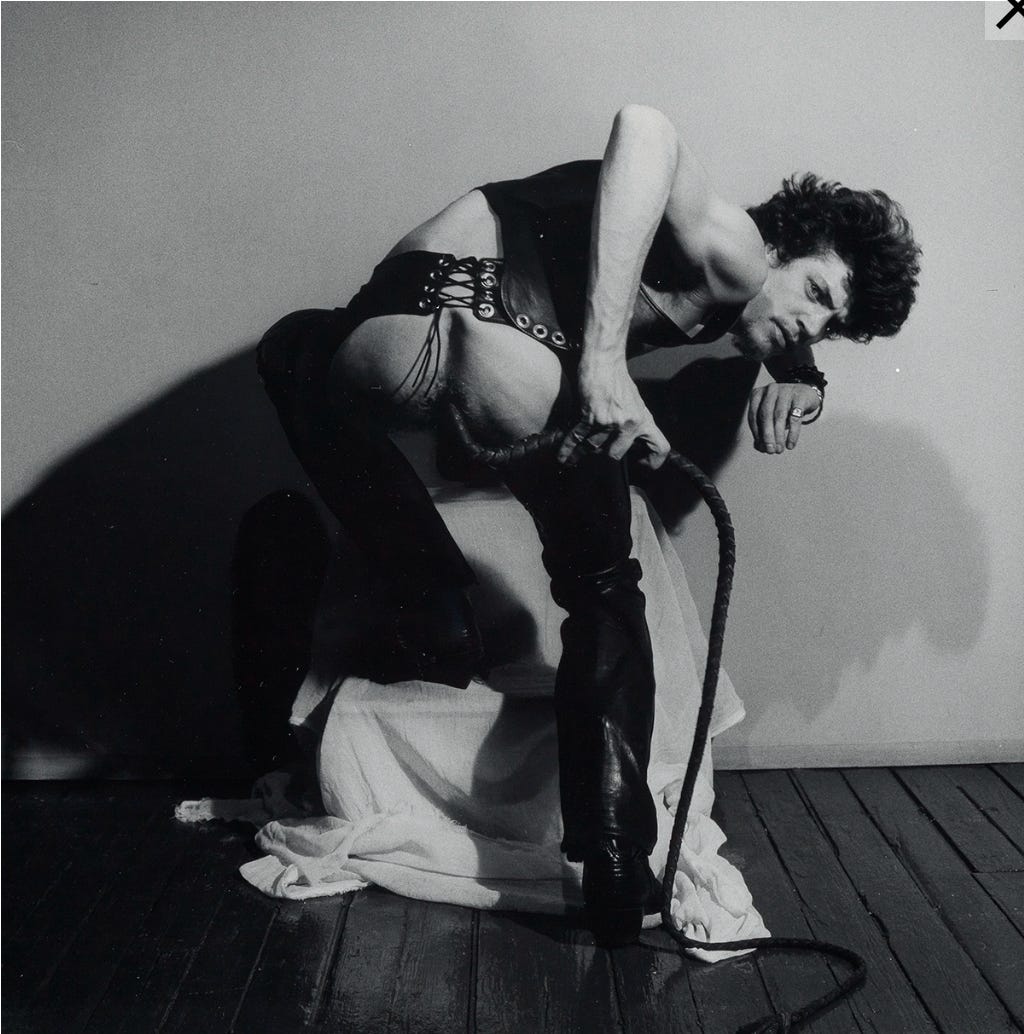

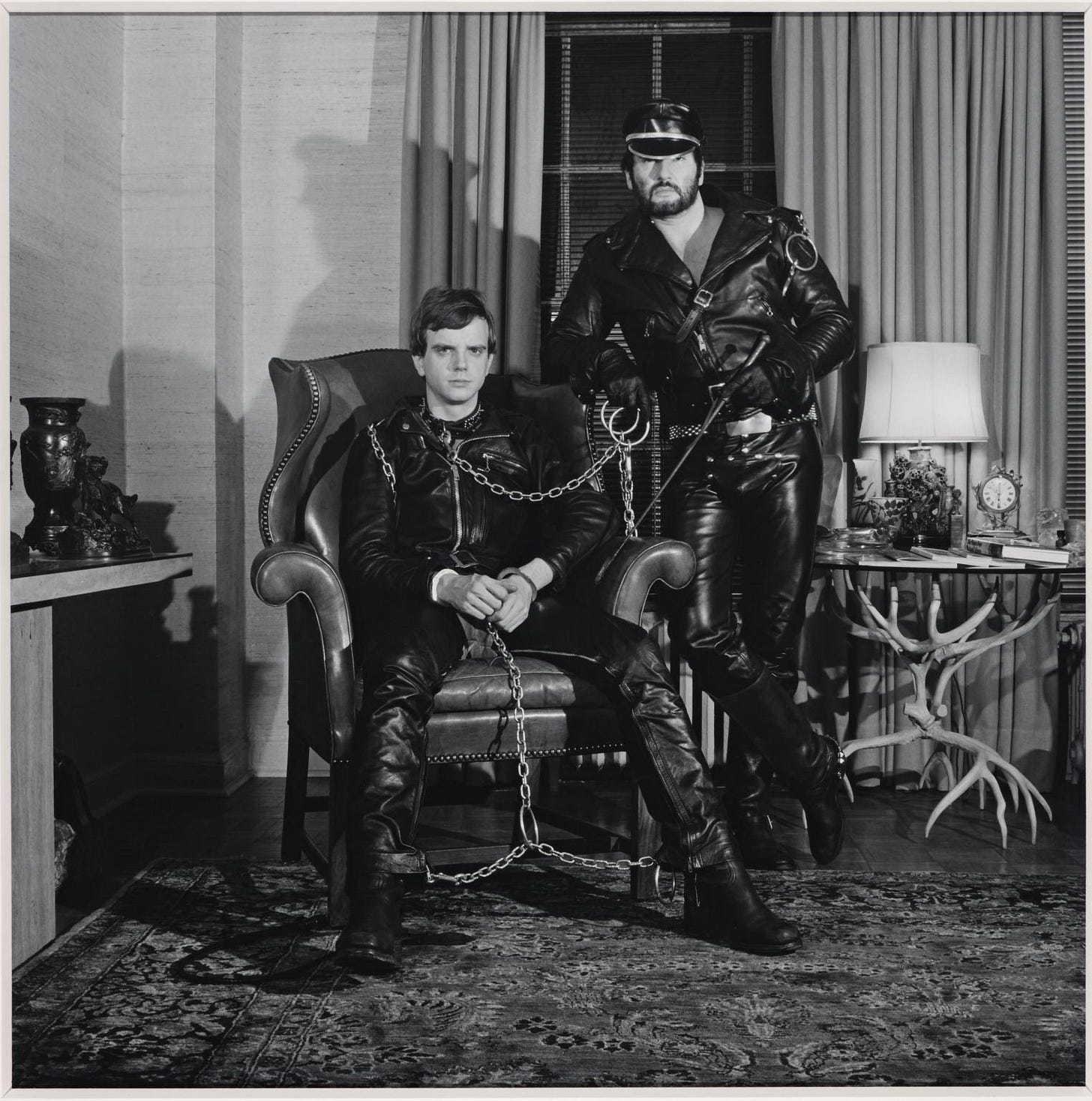

What distinguishes Mapplethorpe’s erotic images is not content alone, but how they are framed. His S&M series, particularly Self-Portrait with Whip (1978), exemplifies this. Mapplethorpe presents himself naked, crouched, with a bullwhip protruding from his anus, posed against a stark black background. The figure is lit like a saint or sculpture; no detail left to chance. Richard Meyer reads this image as a visual oxymoron: “a moment of total abjection rendered in the visual language of sublime control” (Meyer 127). Mapplethorpe’s approach to sadomasochism was not prurient voyeurism but aesthetic anthropology. He was both insider and artist, participant and documentarian. As David Halperin argues, “Mapplethorpe transformed the subcultural spaces of leather bars and backrooms into cathedrals of form, reimagining pain as a structure of intimacy and art” (Halperin 148).

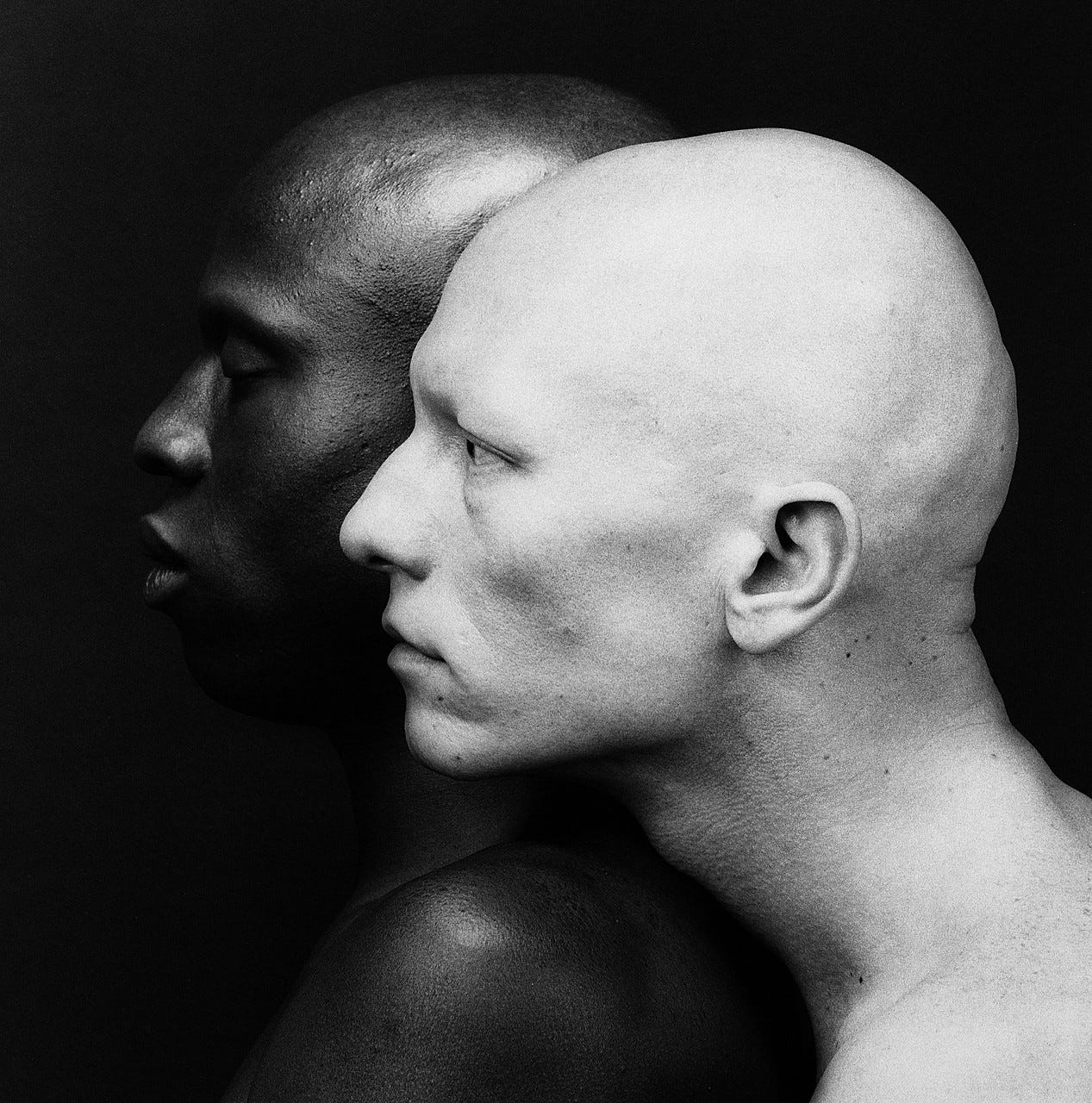

His male nudes, often posed with the serenity of Renaissance martyrs, evoke both erotic pleasure and sacrificial beauty. In Ken Moody and Robert Sherman (1984), two nude men, Moody, a Black man, and Sherman, a white man, are photographed in profile, eyes closed, their heads nearly touching. The composition is symmetrical and serene, with a muted backdrop that highlights the tonal contrast between their skin. The Whitney Museum notes that it “reflects Mapplethorpe’s interest in classical balance while staging race as both visual contrast and erotic dialogue” (Whitney Museum “Ken Moody and Robert Sherman”). Mercer writes that “Mapplethorpe’s images of Black male bodies often walk a tightrope between fetishism and aesthetic admiration, yet Ken Moody and Robert Sherman disrupts this narrative through balanced intimacy” (Mercer 175).

In Thomas (1986), another recurring Black male subject, Mapplethorpe achieves a similar tension between reverence and eroticism. The nude figure stands in stark simplicity against a dark backdrop, calm and poised. Mercer contends that in works like Thomas, Mapplethorpe moves toward “a softened gaze, still sculptural, but more humane” (Mercer 194). The platinum print’s wide tonal range and luminous quality elevate the body into an almost heroic presence (Getty Museum “Ajitto”).

By framing these images with formal rigor, perfect symmetry, sculptural lighting, minimal distractions, Mapplethorpe compels the viewer to confront desire itself as an aesthetic category. He insists that erotic imagery can be high art, not merely private or pornographic.

Mapplethorpe’s archive is an archive of queer memory, not in the sense of factual history, but as José Esteban Muñoz describes, “a constellation of affect, loss, and desire that insists on the visual as a way to dream otherwise” (Muñoz 38). His photographs are less about the specific lives of his subjects than about the social fantasy of queer desire; what it looks like, where it resides, how it defies legibility.

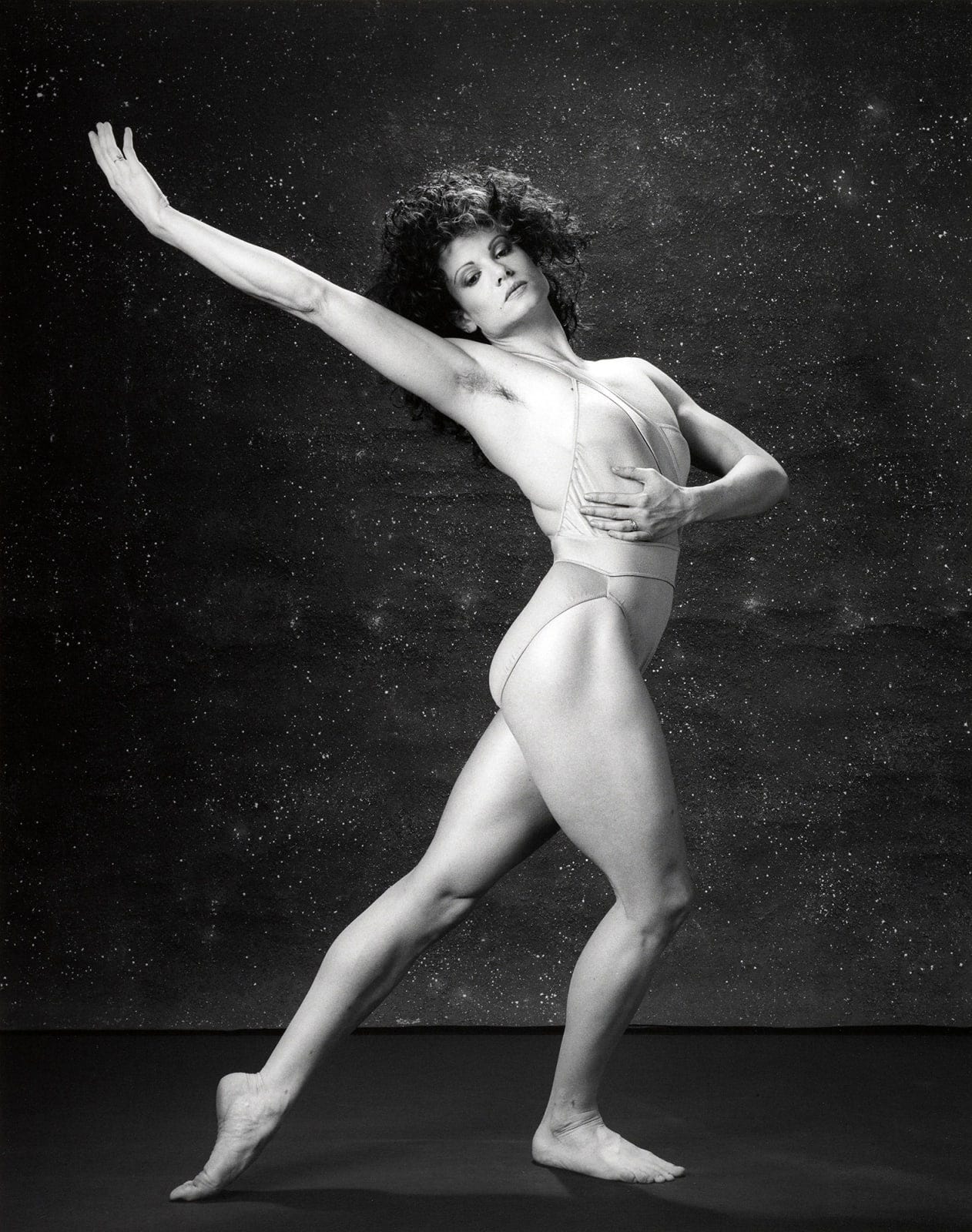

His sustained collaboration with female bodybuilder Lisa Lyon in the early 1980s complicated his presumed misogyny. In over 150 photographs, Lyon is depicted nude, flexing, posing with swords, reclining like a neoclassical heroine. Blessing argues that these images “redefined femininity not as fragility, but as spectacle, strength, and style” (Blessing 54). Lyon herself said she felt seen as a “goddess, a warrior, a myth” (qtd. in Swann Galleries). Through Lyon, Mapplethorpe expanded his archive of desire beyond male eroticism to include a muscular female form that both embraced and transcended classical ideals.

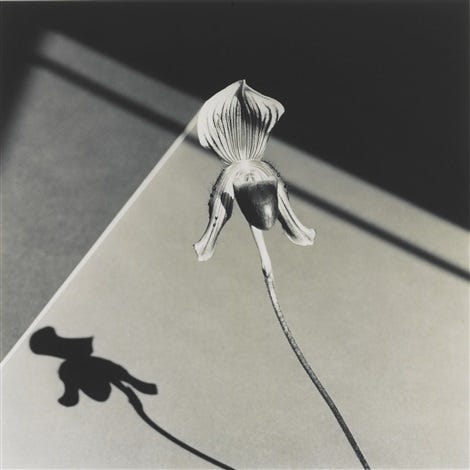

Mapplethorpe’s floral series, Calla Lily (1984), Tulip (1984), and Orchid (1986), function as aesthetic counterparts to his erotic imagery. Roland Barthes notes in Camera Lucida that photography always implicates death: “the photograph is that-has-been” (Barthes 96). For Mapplethorpe, photographing the fleeting perfection of a tulip was no different from capturing the muscular tension of a nude. Both become moments of impossible beauty made still, and both carry undertones of transience.

In Calla Lily, the single bloom is isolated against a dark background, its curves rendered with almost erotic intensity. The Guggenheim Museum observes that Mapplethorpe’s black-and-white floral studies “express a sustained investigation into the visual purity of the photographic object” (Guggenheim “Calla Lily”). As Morrisroe notes, “For Robert, flowers had the curves and shadows of flesh… they weren’t simply plants to him—they were nudes” (Morrisroe 215).

Tulip captures a single tulip’s sensuous arch, neither fully open nor closed. The Whitney Museum explains that Mapplethorpe used flowers “as proxies for erotic forms,” emphasizing “the aesthetics of perfection” (Whitney Museum “Tulip”). In this way, the tulip’s moment of becoming parallels the erotic charge of a poised body.

In Orchid, the petals appear soft, almost bruised, suggesting vulnerability even as they exude sensuality. The Getty Museum writes that Mapplethorpe’s late floral works “combine sensuality with simplicity, using the flower as a metaphor for the human body and spirit” (Getty Museum “Orchid”). These floral images function as quiet memento mori: beauty is fleeting, and yet it commands our gaze.

Through this archive, nudes, bodybuilders, flowers, Mapplethorpe constructs a queer visual genealogy: a network of forms that declare eroticism and difference as sources of aesthetic power.

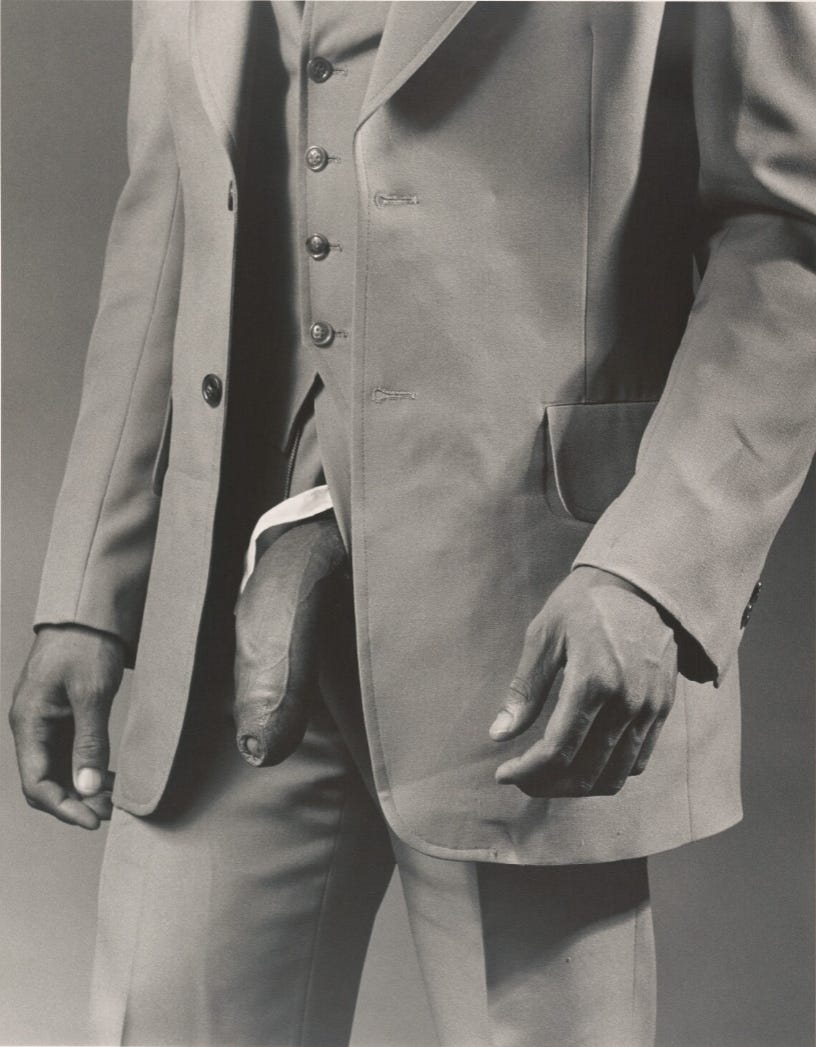

In 1989, several months after Mapplethorpe’s death from AIDS-related complications, his retrospective The Perfect Moment ignited national controversy. Funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), it included explicit images of sadomasochism (e.g., Self-Portrait with Whip) and Black male nudity (e.g., Man in Polyester Suit). Politicians like Senator Jesse Helms and advocacy groups such as the American Family Association launched attacks against what they saw as immoral and indecent art. The resulting conservative backlash led to the NEA’s restructuring and a chilling effect on queer artistic funding (Meyer 143–45).

The crux of the conflict lay not only in what Mapplethorpe showed but in where he showed it: the gallery, a space historically reserved for idealized whiteness, heteronormativity, and patriarchy, became a battleground for queer visibility. Mapplethorpe’s work did not ask for tolerance. It insisted on presence. As Douglas Crimp observed, “Mapplethorpe’s critics feared not only his images, but the possibilities they made visible—the redistribution of desire, the visibility of difference, and the aesthetics of transgression” (Crimp 214).

Man in Polyester Suit (1980) exemplifies the stakes of this debate. The midsection of a Black man wearing a formal suit deliberately displays his genitals, cropped to de-emphasize identity. By juxtaposing respectability (formalwear) and raw eroticism (nudity), Mapplethorpe challenged viewers to reconsider the Black male body’s place in fine art. In the 1989 NEA hearings, Jesse Helms famously decried the photograph as “filthy art” (Meyer 124). Yet Mapplethorpe himself insisted: “The Black male is the most beautiful model… but they’re rarely presented as art” (qtd. in Morrisroe 276). bell hooks would later critique Mapplethorpe’s fetishization of Black male bodies, arguing that his aesthetic often replicated colonialist tropes (hooks). Conversely, Thelma Golden defended the work’s cultural significance, asserting that it exposed, and refused to sanitize, mechanisms of racial and sexual fetishization (Golden 63).

Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter (1979) further illustrates Mapplethorpe’s conflation of formality and deviance. Two white men dressed in leather bondage gear sit stiffly in a pastel living room, complete with floral drapes and a tufted sofa. The jarring dissonance between explicit subcultural identities and a staid domestic setting creates a visual collision that is both humorous and radical. Mercer notes that “Mapplethorpe deliberately placed S&M within the visual syntax of classicism, compelling the viewer to confront their biases within the structure of formal beauty” (Mercer 188). This photograph, included in The Perfect Moment, became a flashpoint in the late-twentieth-century culture wars, showing how even consenting adults’ image could serve as a battleground for public morality (National Galleries of Scotland “Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter”).

Mapplethorpe’s unapologetic insistence on showing queer sexualities inside the museum forced institutions, and audiences, to reckon with their exclusions. The cultural battles over The Perfect Moment revealed not only the power of his images but also how threatened the art establishment remained by non-heteronormative, non-white forms of beauty.

Mapplethorpe’s influence is palpable in the work of contemporary artists who both inherit and challenge his formal rigor and political provocations. Paul Mpagi Sepuya stages queer male nudes in fragmented, self-aware compositions that explicitly reference Mapplethorpe’s classical geometry while insisting on a more layered subjectivity (Sepuya). Zanele Muholi creates self-portraits that reclaim the Black body from both colonial and contemporary fetishism, foregrounding racial and sexual identities that Mapplethorpe’s archive sometimes elided (Muholi). These artists engage with Mapplethorpe not as a saint but as a “problematic ancestor”; a master of form, but also a site of necessary revision.

Recent exhibitions, such as Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now (Guggenheim, 2019), have sought to address the racial dynamics of his work head-on. Curators included critical responses, alternative voices, and Black queer artists to acknowledge that Mapplethorpe’s aesthetic legacy cannot be separated from its historical context or controversies (Guggenheim, 2019). As Thelma Golden aptly wrote, “To love Mapplethorpe is to wrestle with him—to acknowledge his genius, to interrogate his blind spots, and to build on his vision with new, more inclusive vocabularies” (Golden 62).

Mapplethorpe’s floral canon continues to inspire meditations on beauty’s temporality. Photographers like Dawoud Bey and artists such as Catherine Opie expand his floral formalism into questions of ecological fragility and queer community preservation, illustrating that his images of flowers remain potent symbols for both eroticism and ephemerality (Bey; Opie).

Mapplethorpe’s S&M and homoerotic portraits have also influenced performance artists who stage their own bodies as sites of resistance. Doug Aitken, for example, references the visual syntax of Self-Portrait with Whip in immersive installations that blur boundaries between viewer and performer (Aitken). Meanwhile, Cassils uses light and shadow in live performances to evoke Mapplethorpe’s chiaroscuro nudes, insisting on the physical presence of queer and trans bodies (Cassils).

Robert Mapplethorpe made beauty confrontational. He placed queer eroticism, Black masculinity, S&M ritual, and floral sensuality into frames of classical perfection; making the forbidden not only visible but sublime. His photographs sparked outrage, scholarship, imitation, and transformation. They challenged institutions to reckon with their exclusions and audiences to examine their desires.

Today, Mapplethorpe remains a paradox: a queer icon and a problematic favorite, a formalist and a radical, a sculptor of bodies and a breaker of norms. But perhaps this is exactly what makes his work endure. As Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick writes, “Queerness is a kind of looking that never stops asking what else it could be” (Sedgwick 9). Mapplethorpe’s images do exactly that....they keep asking.

References:

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard, Hill and Wang, 1981.

Bey, Dawoud. Dawoud Bey: Black Chronicle. Aperture, 2020.

Blessing, Jennifer. Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition: Photographs and Mannerist Prints. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2004.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1990.

Cassils. Artist Statement. Cassils Official Website, www.cassils.com. Accessed 9 June 2025.

Crimp, Douglas. On the Museum’s Ruins. MIT Press, 1993.

Golden, Thelma. Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994.

Halperin, David M. Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography. Oxford University Press, 1995.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. South End Press, 1992.

Mercer, Kobena. Skin Head Sex Thing: Racial Difference and the Homoerotic Imaginary. Art Journal, vol. 49, no. 3, 1990, pp. 171–178.

Meyer, Richard. Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Morrisroe, Patricia. Mapplethorpe: A Biography. Random House, 1995.

Muholi, Zanele. Masks and Performers. Aperture, 2019.

Mumford, Ginnie, and Glenn Ligon. Introduction. Guggenheim Magazine, Spring 2019, pp. 1–12.

Mumford, Ginnie, and Christian Viveros-Fauné, editors. Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2019.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York University Press, 2009.

National Galleries of Scotland. Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter (1979). National Galleries of Scotland, www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/90694. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

National Galleries of Scotland. Self Portrait (1980). National Galleries of Scotland, www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/130229. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

National Galleries of Scotland. Self Portrait (1988). National Galleries of Scotland, www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/90652. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Opie, Catherine. Artist Statement. Catherine Opie Official Website, www.catherineopie.com. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Sepuya, Paul Mpagi. Studio Bodies. Aperture, 2022.

Smith, Patti. Just Kids. Ecco, 2010.

Swann Galleries. A New Muse: Robert Mapplethorpe and Lisa Lyon. Swann Galleries, www.swanngalleries.com/news/photographs-and-photobooks/2020/04/robert-mapplethorpe-and-lisa-lyon-collaboration/. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Whitney Museum of American Art. Ken Moody and Robert Sherman. Whitney Museum of American Art, www.whitney.org/collection/works/11520. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Whitney Museum of American Art. Tulip. Whitney Museum of American Art, www.whitney.org/collection/works/11521. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Guggenheim Museum. Calla Lily. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, www.guggenheim.org/artwork/4364. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Getty Museum. Ajitto. J. Paul Getty Museum, www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/10A2NS. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

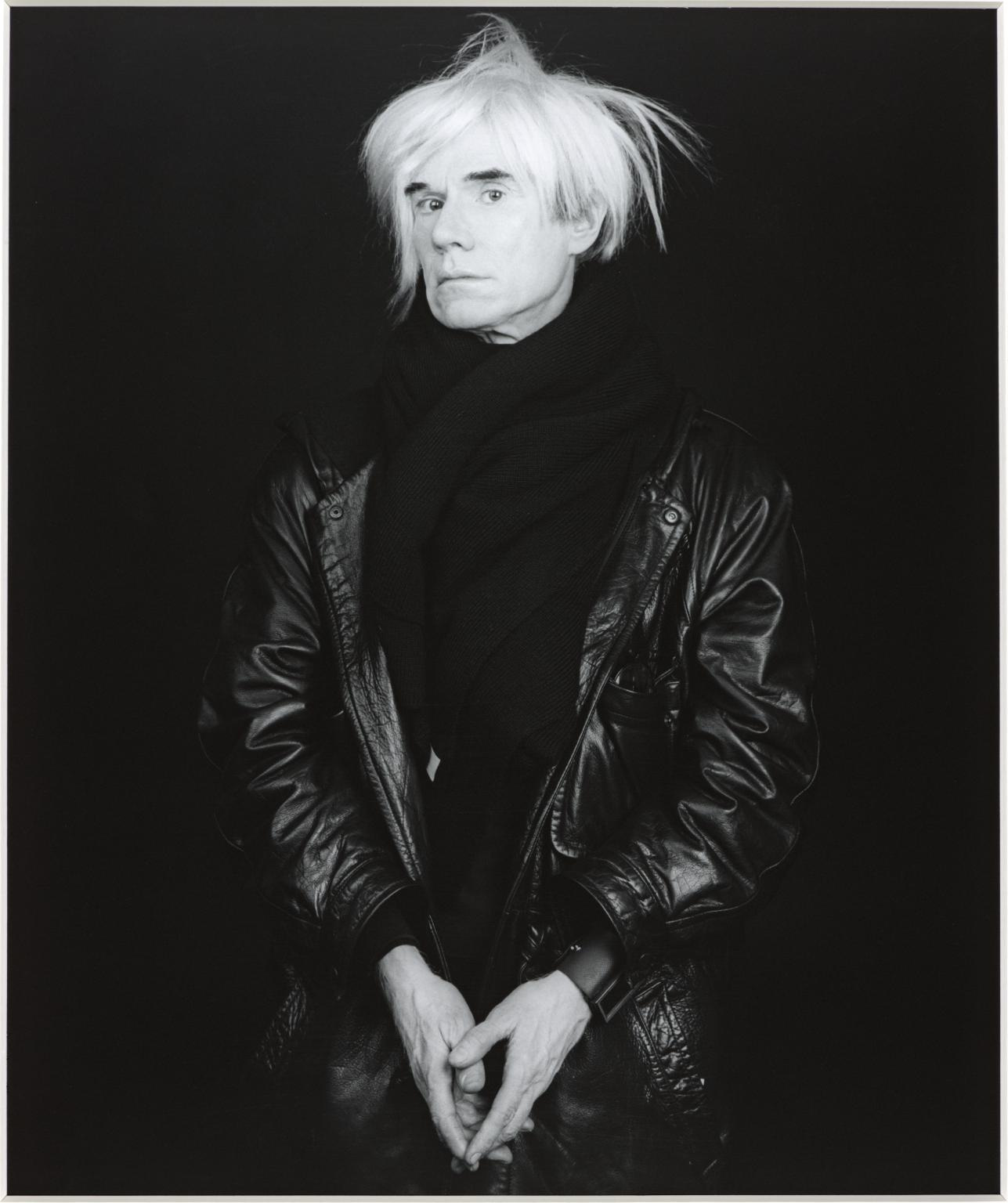

Getty Museum. Andy Warhol. J. Paul Getty Museum, www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/10A2NS. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Getty Museum. Orchid. J. Paul Getty Museum, www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/10A2NS. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet. University of California Press, 1990.

Mapplethorpe's work is stunning, and like so many other artists, there is a person or persons in his background, whether it's a spouse, a patron, what have you who can't be ignored. In Mapplethorpe's case, it was his printer, Tom Baril, who was the person who made those prints. Mapplethorpe, fair enough, had very little interest in film development or printing. His strength and genius was in other areas.

Thanks for this reminder about Mapplethorpe's brilliance. and the overview of his work. He is still so relevant and fresh, especially in these times.