How Does Art Reflect Political Ideologies, Serve as Propaganda, and Respond to the Impact of World War II?

#FrequentlyAskedQuestions

Art has historically been both a mirror of societal values and a medium for shaping political ideologies. It exists not only to document or celebrate but also to question, critique, and catalyze change. Examining the intersection of art and politics reveals how creativity reflects prevailing ideologies, serves as a tool for propaganda, and evolves in response to pivotal global events like World War II.

Throughout history, art has been employed to reflect and reinforce political ideologies, serving as a cultural testament to the values and power dynamics of its era. In ancient societies, monumental works often portrayed rulers as divine or semi-divine figures to solidify their authority. For example, the Stele of Hammurabi positioned the Babylonian king as a lawgiver under divine endorsement, while Ancient Egyptian artworks depicted pharaohs as intermediaries between gods and humanity, reinforcing hierarchical theocratic power structures (Chilvers and Glaves-Smith).

In the modern era, art continued to act as a visual language of political ideologies. The Baroque grandeur of Louis XIV’s Versailles exemplified how art could symbolize absolute monarchical control. The aesthetic conveyed a sense of order and divine right, aligning with the king’s political philosophy. Similarly, during the Soviet era, Socialist Realism emerged as the state-mandated art form, glorifying industrial progress, agricultural success, and the proletariat. Vera Mukhina’s Worker and Kolkhoz Woman epitomized this style, visually embodying Communist ideals of collective labor and progress (Werckmeister). In the United States, the New Deal arts programs of the 1930s, such as those funded by the Works Progress Administration, commissioned murals and sculptures that celebrated democracy, resilience, and the dignity of labor, embodying the nation’s ideological commitment to equality and hope (Arnason and Mansfield).

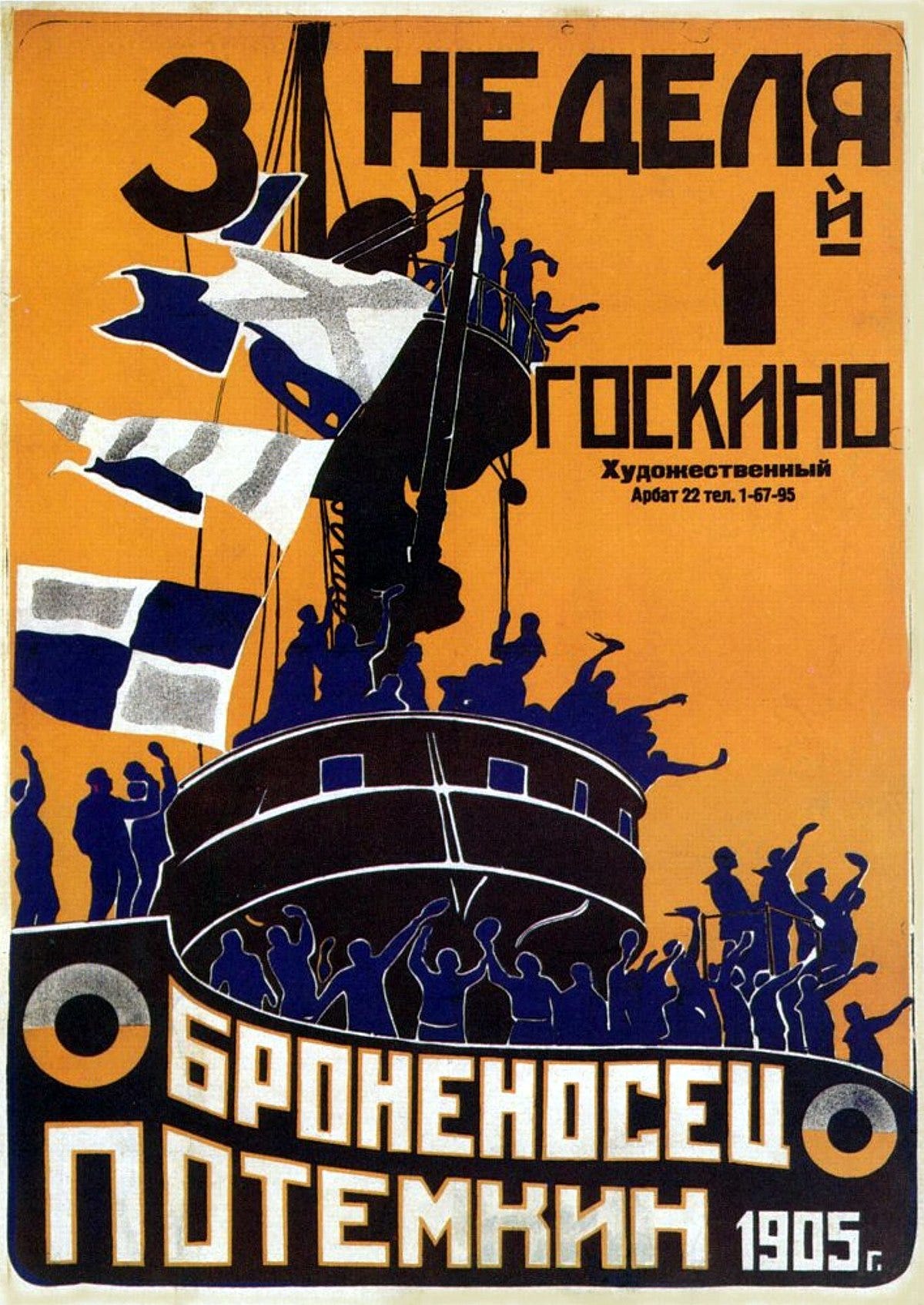

Art has frequently been wielded as a tool of propaganda to shape public perception and galvanize support for political agendas. In totalitarian regimes, visual culture became a powerful instrument for indoctrination. Nazi Germany, for instance, employed art and cinema to glorify the Aryan ideal and Hitler’s leadership. Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will exemplified how innovative cinematography could magnify a political ideology’s reach and resonance (Taylor). Similarly, Soviet propaganda films like Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin celebrated revolutionary zeal, fostering allegiance to Communist ideals.

In democratic contexts, propaganda often took subtler forms, yet its impact was no less significant. During World War II, the U.S. government commissioned artists like Norman Rockwell, whose Four Freedoms series visually articulated the core values of democracy and liberty. Posters in Britain, such as “Keep Calm and Carry On,” sought to bolster civilian morale during times of hardship. In Mexico, muralists such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco used their works to critique colonialism and capitalism, celebrating indigenous identity and envisioning a future rooted in social justice (Chilvers and Glaves-Smith).

World War II was a watershed moment that profoundly influenced art and artists, reshaping the global cultural landscape. As Europe became engulfed in war, many artists fled to the United States, shifting the center of the art world from Paris to New York City. This migration catalyzed the rise of Abstract Expressionism, a movement rooted in freedom of expression and individuality. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning broke from representational art, reflecting a broader societal desire to reject authoritarianism and embrace personal autonomy (Arnason and Mansfield).

In Europe, the devastation wrought by the war spurred existential introspection among artists. Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures, such as Walking Man, captured the fragility and perseverance of the human spirit. Pablo Picasso’s Guernica became an enduring anti-war symbol, its fragmented forms and muted palette conveying the chaos and suffering of the Spanish Civil War, presaging the global conflict to come (Foster et al.). Additionally, the Holocaust and the use of nuclear weapons left indelible marks on the artistic psyche, inspiring works that grappled with themes of destruction, morality, and survival.

Art also played a critical role in resistance movements during the war. In Nazi-occupied France, artists like Jean Fautrier used abstraction and symbolism to critique the brutality of fascism. Similarly, underground graffiti and posters served as tools of resistance, subtly undermining enemy propaganda and rallying the oppressed.

Beyond reflecting and propagating political ideologies, art has historically been a means of resistance and renewal. The French Revolution saw Jacques-Louis David’s works, such as The Death of Marat, transform into political statements that celebrated revolutionary ideals and critiqued tyranny. In contemporary contexts, street art has emerged as a potent form of resistance. Artists like Banksy have used public spaces to critique consumerism, war, and authoritarianism, proving that art can still challenge political systems and spark critical dialogue (Chiu).

In the aftermath of political and social turmoil, art frequently serves as a vehicle for renewal. Abstract Expressionism’s emphasis on spontaneity and emotional depth symbolized a postwar rejection of rigidity and control. Similarly, the reconstruction of European cultural institutions and the establishment of museums like the Museum of Modern Art in New York City reflected an effort to preserve and promote artistic innovation as a testament to human resilience (Arnason and Mansfield).

Art’s multifaceted relationship with politics underscores its enduring relevance as a reflection, reinforcement, and critique of power structures. Whether as propaganda or resistance, art shapes and is shaped by the political currents of its time, documenting humanity’s triumphs and struggles while offering visions of renewal. From ancient empires to modern democracies, art has been a constant reminder of the enduring power of creativity to navigate and transcend the complexities of political life.

References:

Arnason, H. Harvard, and Elizabeth C. Mansfield. History of Modern Art. Pearson, 2012.

Chilvers, Ian, and John Glaves-Smith. A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Chiu, Melissa. Art and China’s Revolution. Asia Society, 2017.

Foster, Hal, et al. Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism. Thames & Hudson, 2004.

Taylor, Brandon. Art and Propaganda in the Twentieth Century. Abrams, 1991.

Werckmeister, O.K. Icons of the Left: Benjamin and Eisenstein, Picasso and Kafka after the Fall of Communism. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Loved the essay. Well-grounded with excellent examples, I still remember Mukhin's sculpture of Worker and Kolkhoznithsa. Interesting, what did they do with it when the USSR collapsed?In the former USSR politicians defined the position of art and artists, I write about this theme also in Poets Before and After Revolution. The real Art was completely destroyed by the Communsts. The same in Hitler's Germany and later in the socialistic East Germany.