Colonization has left an indelible mark on Indigenous art forms, profoundly altering their creation, meaning, and transmission. Colonial policies were often designed to suppress Indigenous cultures, particularly their art forms. This suppression was evident in practices that outlawed traditional rituals and ceremonies. For example, in Canada, the Indian Act of 1876 banned the Potlatch ceremony of the Northwest Coast peoples, a communal event central to their social and artistic expressions. During these ceremonies, masks, totems, and regalia( integral to Indigenous storytelling) were used but were confiscated and destroyed by authorities.

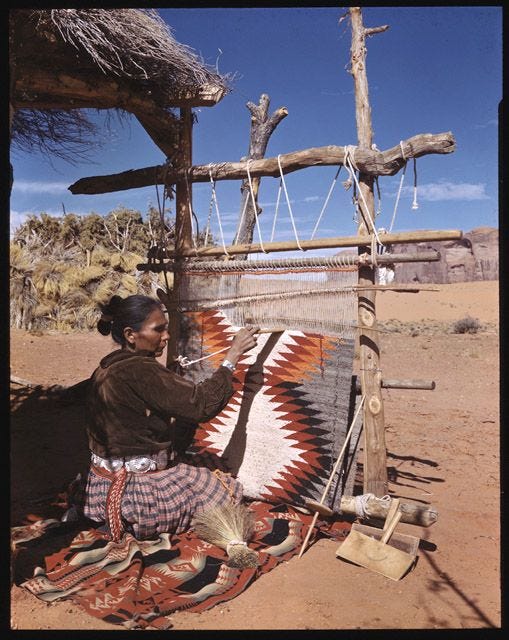

The Christian missionary influence also sought to replace Indigenous art with European styles. In the case of the Navajo in the United States, missionaries discouraged weaving and other traditional crafts in favor of vocational skills such as carpentry. Similarly, Australian Aboriginal artists were often coerced into creating religious art for churches while abandoning traditional Dreamtime painting, which served as a connection to ancestral stories and cosmology (Ryan 34).

The impact was twofold: traditional techniques began to vanish, and Indigenous artists were forced to adapt their work to fit Western expectations. By the 19th and 20th centuries, many Indigenous craftspeople in North America were producing "souvenirs" for tourists, such as beadwork or pottery, rather than items of cultural significance.

Colonial exploitation of Indigenous art often stripped it of its original context and purpose. Museums and collectors appropriated sacred objects, presenting them as "artifacts" devoid of their spiritual or cultural meaning. This was particularly pronounced during the late 19th century, with institutions such as the British Museum and the Smithsonian acquiring Indigenous items through unethical means.

For example, the Benin Bronzes, looted by British forces in 1897, showcase how colonial powers exploited Indigenous artistry. These intricately crafted sculptures from the Kingdom of Benin (modern-day Nigeria) were stripped of their historical and cultural significance, becoming trophies of imperial conquest (Eyo and Willett 62).

In North America, the mass removal of totem poles from the Pacific Northwest Coast illustrates how cultural symbols were commodified. These poles, deeply rooted in storytelling and lineage, were often taken to museums or private collections in Europe and the United States without the consent of the Indigenous communities.

The commodification extended to fashion, where Indigenous designs and motifs, such as Navajo patterns, were copied by brands without acknowledgment or compensation. This appropriation devalued the original art forms while profiting colonial systems.

The forced displacement of Indigenous communities during colonization severed them from the natural environments that inspired and provided materials for their art. Plains tribes in the United States, for instance, relied on buffalo for tools, clothing, and ceremonial objects. The near-extinction of the buffalo in the late 19th century, driven by settler overhunting, disrupted these art forms (Calloway 123).

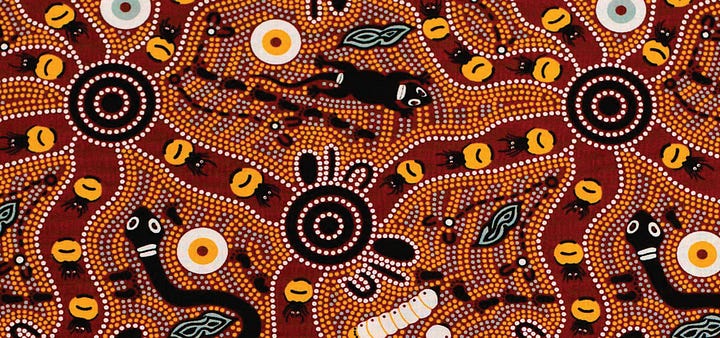

Similarly, Australian Aboriginal communities, displaced to reservations, could no longer access ochres used for painting. This displacement altered the content and materials of their art, as seen in the transition from sand or bark paintings to acrylic canvases in the Papunya Tula movement. While the latter gained global recognition, it was born out of necessity rather than choice.

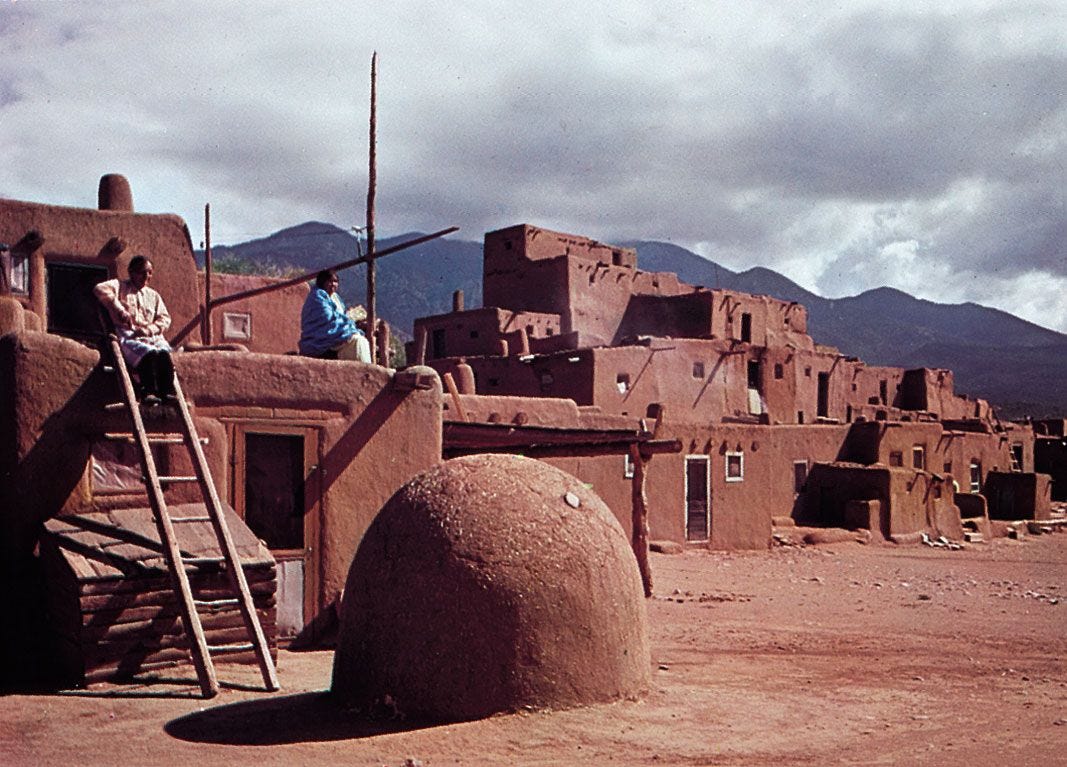

Indigenous architecture also suffered. For example, the pueblo-building traditions of the Hopi in the Southwest United States faced challenges as settlers diverted water sources and introduced new materials, undermining the sustainability of their ancestral practices.

Despite colonization, Indigenous art became a vehicle for resistance and resilience. Artists subverted colonial narratives by embedding traditional symbols into contemporary works, challenging the erasure of their identities.

The Māori of New Zealand revitalized the art of tā moko (tattooing) in the late 20th century after decades of colonial suppression. Tā moko, a sacred practice, had been stigmatized as "savage" during British rule but was reclaimed as a form of cultural pride and resistance (Te Awekotuku 79).

In North America, the ledger art tradition of Plains tribes emerged during the late 19th century as a response to displacement. Indigenous prisoners at Fort Marion, Florida, created vibrant drawings on ledger paper, combining traditional storytelling with materials introduced by settlers. This practice not only preserved their stories but also subverted colonial expectations of "acceptable" art.

Today, Indigenous artists like Jeffrey Gibson and Kent Monkman use contemporary media to challenge colonial histories. Monkman’s paintings, for instance, reframe classical European art tropes to center Indigenous perspectives, directly addressing the historical injustices perpetuated by colonization.

Efforts to decolonize Indigenous art involve reclaiming control over cultural heritage and challenging institutional biases. Repatriation movements have gained momentum, with Indigenous communities demanding the return of stolen artifacts. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 marked a significant step in the United States, enabling tribes to reclaim sacred objects and human remains from museums.

Indigenous curators are also reshaping narratives in art institutions. The National Gallery of Canada’s Indigenous and Contemporary Art department, led by Indigenous curators, has reframed exhibits to emphasize the continuity of Indigenous art traditions rather than relegating them to the past (Hill 94).

Education plays a crucial role in these efforts. Initiatives like the Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Corporation in Australia empower Indigenous artists to maintain traditional practices while navigating the global art market, ensuring cultural sustainability and economic autonomy.

Colonization deeply impacted Indigenous art forms by disrupting traditional practices, appropriating cultural symbols, and displacing communities. Yet, Indigenous artists have continuously adapted, resisted, and reclaimed their traditions. By addressing these historical injustices and supporting decolonization efforts, we can honor the resilience of Indigenous art and recognize its vital role in shaping cultural identity.

References

Calloway, Colin G. First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History. Bedford/St. Martin's, 2016.

Eyo, Ekpo, and Frank Willett. Treasures of Ancient Nigeria: A Legacy of Two Thousand Years. Alfred A. Knopf, 1980.

Hill, Richard W. Decolonizing the Museum: The National Gallery of Canada's Indigenous Vision. Canadian Art, vol. 33, no. 2, 2016, pp. 94-101.

Ryan, Judith. Spirit in Land: Bark Paintings from Arnhem Land. National Gallery of Victoria, 2005.

Te Awekotuku, Ngahuia. Māori Women and Culture in Tattooing. Reed Publishing, 2003.

A fascinating and at times gut-wrenching read. Hopefully the campaigns to return stolen sacred artwork from colonial museums to indigenous communities will bear fruit soon, thanks in part to voices like yours.

Thank you… Something to think about. I love the art and the colours. 💥