Founded in 1972 at the height of the Asian American civil rights and cultural movement, Kearny Street Workshop (KSW) is the oldest continuously operating Asian Pacific American multidisciplinary arts organization in the United States. It began as a grassroots artists’ collective in San Francisco’s Chinatown/Manilatown neighborhood, initially sharing a storefront space in the landmark International Hotel (I-Hotel). The founders, Jim Dong, Lora Jo Foo, and Mike Chin, among others, were activists involved in the Asian American Movement and envisioned KSW as a community art space “locally run and for the people,” blending art with activism. Early on, KSW participants, guided by artists like Bernice Bing (a Neighborhood Arts Program liaison), established classes and workshops in photography, creative writing, and silkscreen printing for Asian American youth and activists. Within its first few years, hundreds of community members were attending salons, workshops, and exhibitions, reflecting a pent-up demand for Asian American creative outlets.

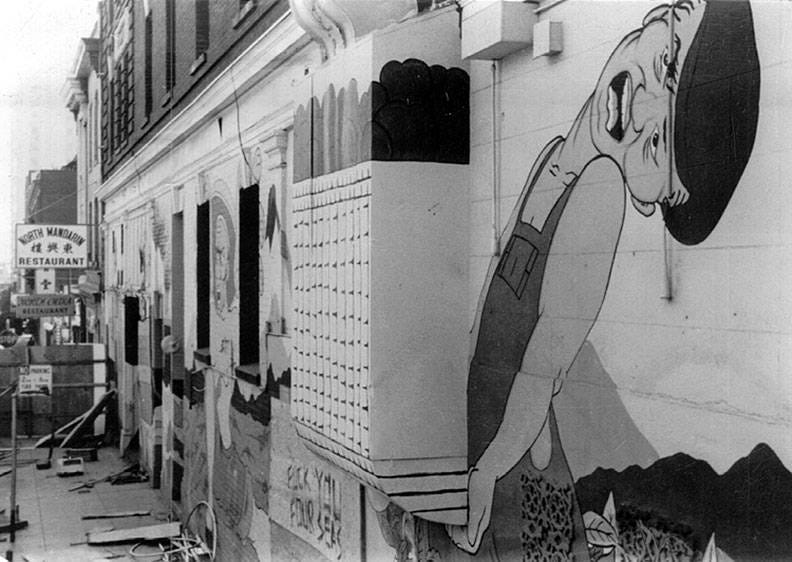

KSW’s inception in the 1970s was intrinsically tied to the era’s social movements, and it became a model for community-centered art practice. During the protracted struggle to save the I-Hotel, a low-income residence for many elderly Filipino and Chinese immigrants, KSW artists played a key role in developing Asian American activist iconography. They painted a block-long mural on the I-Hotel’s exterior and plastered Chinatown, Manilatown, and Japantown with silkscreen posters supporting the tenants’ anti-eviction fight. KSW members also organized rallies, poetry readings, and exhibits on housing justice, making art a form of protest and community storytelling. As former KSW director Nancy Hom observed, “the struggles of the neighborhood”, battles over low-income housing, labor strikes, and gentrification, directly defined the art produced by KSW in this period. In this way, the Workshop’s art historical significance lies in its pioneering synthesis of art and activism: it forged a distinctly Asian American visual language of resistance (through murals, prints, and graphics) and proved that community art could empower marginalized voices during the 1970s civil rights era.

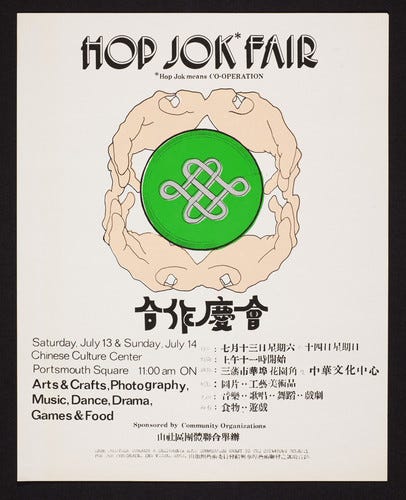

Beyond its visual arts output, KSW served as an anchor for Asian American cultural life in the Bay Area. It provided an inclusive gathering space at a time when Asian American artists were virtually absent from mainstream galleries and institutions. Notably, KSW quickly expanded from a primarily Chinese American focus to a pan-Asian Pacific American scope, holding workshops that brought together artists of Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, and other Asian backgrounds. This multiethnic inclusion fostered inter-community solidarity and helped define a broader Asian American identity in the arts. KSW also ventured into performing arts and literature: it hosted poetry readings (including early works by writers like Al Robles and Jessica Hagedorn) and music performances, and even launched its own press to publish Asian American writers. In 1981, KSW founded the Asian American Jazz Festival, which became a major annual event celebrating Asian Americans in music and continues to thrive decades later. Such programs not only nurtured artists but also introduced Asian American art and culture to wider audiences. KSW’s community festivals, for example, the “Hop Jok Fair,” which combined an art fair with social services outreach in Chinatown, exemplified its holistic approach to culture and community empowerment. By the 1980s, KSW had established itself as a “significant social force and locus of creativity” in San Francisco’s Asian American community.

Surviving challenges such as eviction from the I-Hotel (which was tragically demolished in 1977), KSW persisted and evolved. It relocated several times, from North Beach to Chinatown to South of Market, adapting its programming to the changing needs of the community. In 1995, KSW formalized its structure with a board of directors and non-profit status, ensuring its longevity as an institution. Entering the 21st century, KSW shifted from being primarily an activist workshop to also being an incubator for emerging Asian Pacific American artists. It launched APAture in 1999, an annual multidisciplinary arts festival dedicated to showcasing young APA artists in fields ranging from visual arts to music, film, comics, and performance. APAture was explicitly designed as a springboard for new talent, a place where artists could debut their work, build networks, and then “graduate” to successful careers in the broader arts industry. Indeed, several APAture alumni later rose to prominence: for example, comic artist Hellen Jo first exhibited at APAture 2005 before going on to work on the acclaimed show Steven Universe, and comedian Ali Wong recalls her “very first real show” being an APAture stand-up night, an experience she called “electric” and foundational to her career. Likewise, comedian Hasan Minhaj honed his craft at APAture’s 2008 showcase before achieving national fame. By cultivating such talents, KSW and APAture have created a self-determined space for APA creatives to find their voice and community. As KSW Artistic Director Jason Bayani has noted, giving artists of color a platform is inherently powerful: “Art made by people of color is inherently political… it gives us agency over our narratives”. After over 50 years, KSW remains a vital institution, “a nationally acclaimed non-profit… that continues to operate today” , proving the lasting impact of a community-based arts movement that began in a small Chinatown storefront. It stands as a living legacy of the 1970s Asian American movement, continuing to adapt and empower new generations in the arts while honoring its activist roots.

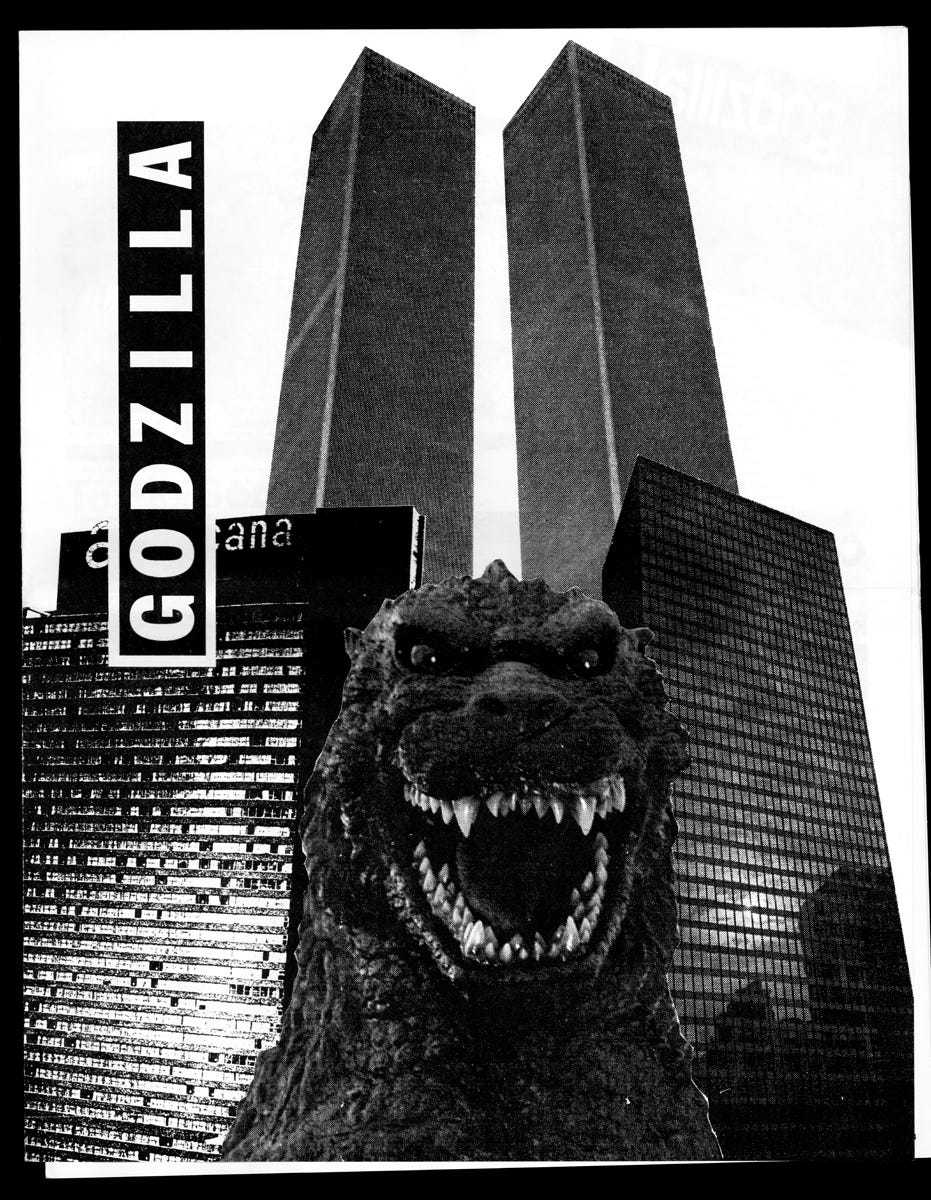

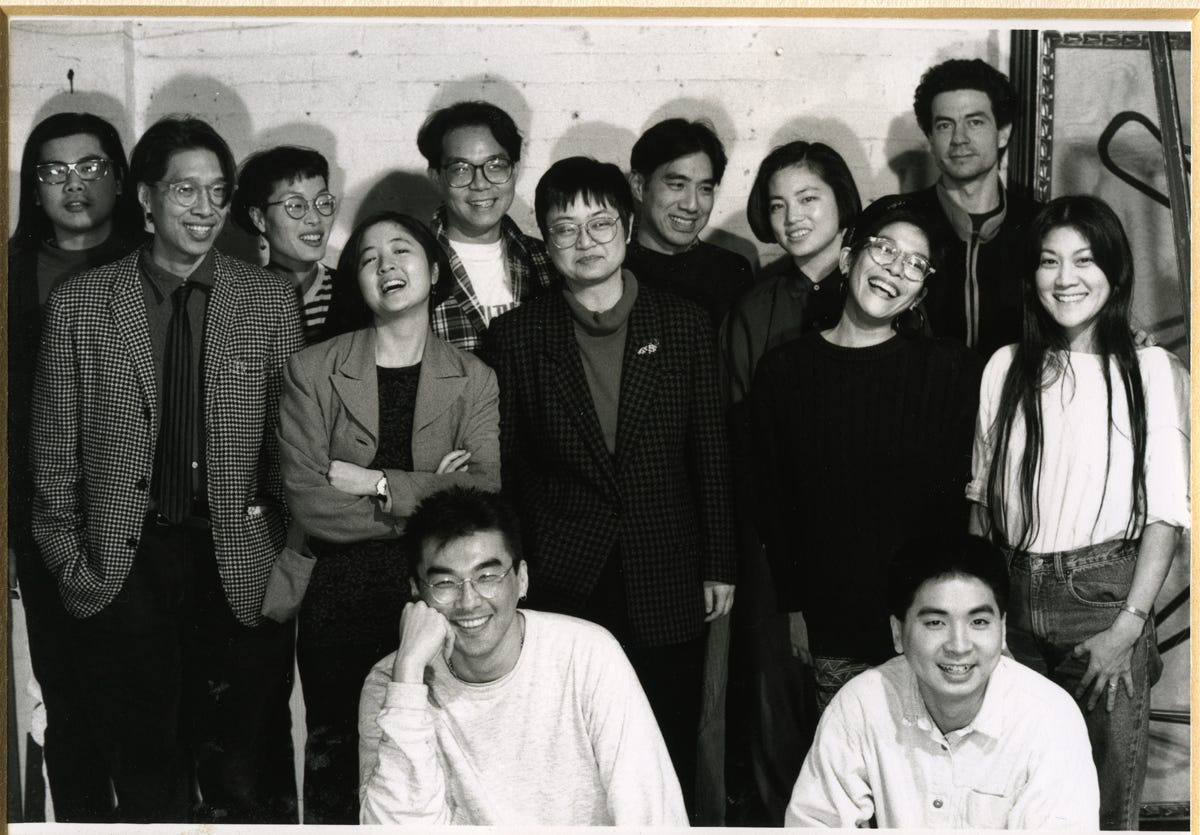

In the early 1990s, amid a growing debate over multiculturalism in the American art world, a group of New York–based Asian American artists, curators, and critics formed Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network. Established in 1990 by artists Ken Chu and Bing Lee and art historian Margo Machida (among others), Godzilla was created to address the historic exclusion of Asian American artists from mainstream galleries, museums, and critical discourse. The founders initially convened to discuss bold ideas, perhaps founding an Asian American contemporary art museum or journal, before settling on a pan-Asian advocacy network with a provocatively playful name: “Godzilla.” As described in a retrospective account, the collective adopted the moniker of the Japanese movie monster as a tongue-in-cheek symbol of disruptive power, “a monster that threatens to topple everything in its way”, endowing Asian Americans (often stereotyped as a “model minority”) with a pop-culture persona of force and visibility. This irreverent yet pointed stance set the tone for Godzilla’s approach to activism within the art world.

Godzilla’s formation came at a pivotal moment in art history when institutions were being challenged to diversify their exhibits and collections. In 1990, the same year the group began, New York’s New Museum, Studio Museum in Harlem, and others co-presented The Decade Show, one of the first major exhibitions to acknowledge multicultural contemporary art. Machida’s essay “Seeing Yellow,” written for that show, articulated the need for a new framework to understand Asian American art beyond Eurocentric and orientalist tropes. Godzilla emerged to build that framework in practice. Its mission was to support the production of critical discourse around Asian American art and to increase the visibility of Asian American artists, curators, and writers who were navigating a predominantly white, exclusionary art establishment. In concrete terms, Godzilla functioned as a collective and a communications network. It organized group exhibitions, published newsletters and written symposia, and facilitated dialogue on issues of identity, racism, and representation in contemporary art. Importantly, Godzilla had an activist edge: the group penned open letters and protest statements to major museums and arts organizations, calling out the underrepresentation of Asian American artists and curators. Throughout the 1990s, Godzilla members consistently confronted topics such as Western imperialism in art, stereotypes of Asian sexuality and gender, and even urgent social crises like the impact of the AIDS epidemic on Asian American communities. This positioned Godzilla at the forefront of a broader multicultural activist movement in the arts, alongside peers like the Black and Latinx artists’ coalitions of the era.

A defining feature of Godzilla was its pan-Asian, diasporic scope. The collective welcomed Americans of East, Southeast, and South Asian descent (the membership included Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Filipino, South Asian, Pacific Islander, and other backgrounds) and explicitly discussed whether to emphasize a pan-Asian unity or highlight specific ethnic identities within the network. In 1995, reflecting an evolving understanding of pan-ethnic identity politics, Godzilla even broadened its official subtitle from “Asian American Arts Network” to “Asian American Pacific Islander Arts Network,” presaging the now-common “AAPI” term and acknowledging a more inclusive coalition. This expansive approach allowed Godzilla to explore a wide spectrum of aesthetic styles and cultural perspectives. The art associated with Godzilla and its members ranged from conceptual installations to traditional media, all filtered through the lens of diaspora experience. For instance, notable Godzilla-affiliated artists included Yong Soon Min, whose conceptual works examine Korean diasporic identity; Tomie Arai, known for community-based murals and printmaking; Byron Kim, whose abstractions (like Synecdoche, 1991) subtly invoke racial color politics; Mel Chin, blending environmental activism and sculpture; and Hung Liu, a Chinese American painter who incorporated historical imagery to challenge narratives. Many of these artists later entered the mainstream canon, a testament to the groundwork laid by Godzilla’s advocacy.

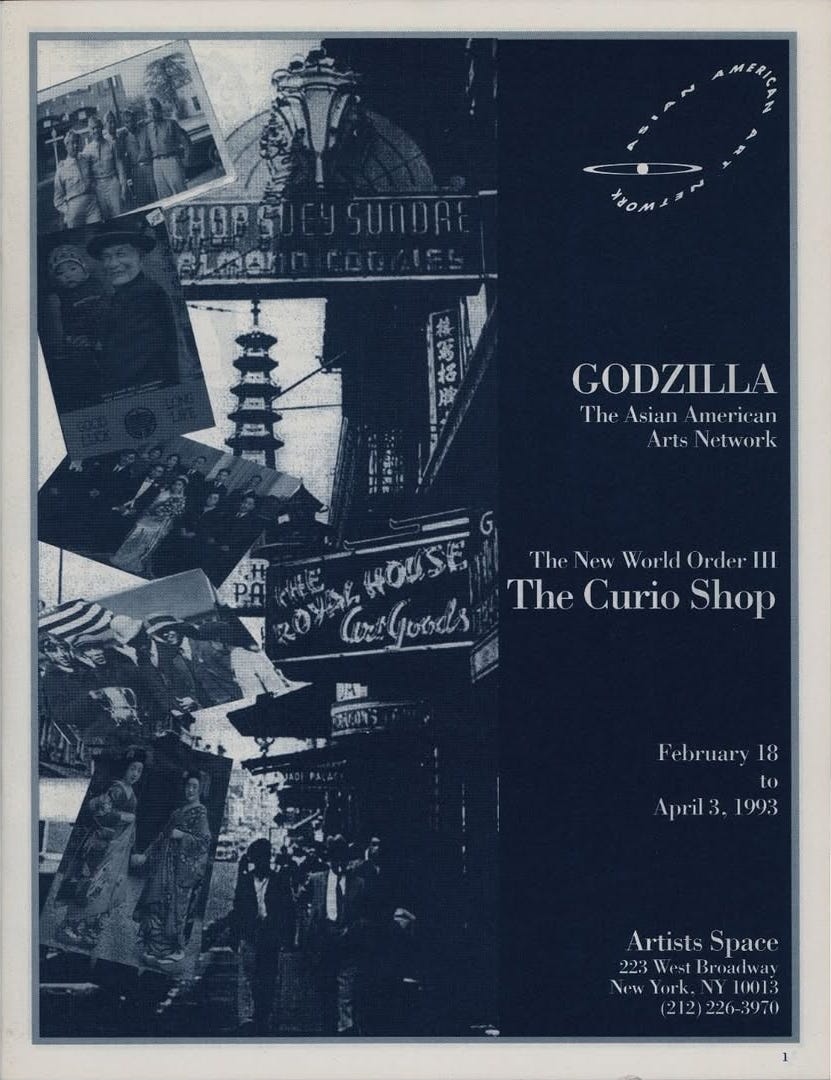

Godzilla’s impact on the cultural landscape was significant during its active decade and beyond. Operating out of New York City, the group served as both a support system and a pressure group. Internally, it was a nurturing community where emerging Asian American artists and curators could find mentorship and collaborators in an often-isolating art scene. Externally, Godzilla was highly visible through its events and interventions. One notable project was The Curio Shop, a 1993 installation presented at Artists Space as part of the exhibition New World Order: Fictionality and Community in Contemporary Art. In this satirical “shop” installation, Godzilla artists collectively critiqued racialized images of Asians, a direct attack on the exotification and commodification of Asian culture in Western society. The project’s intellectual framework drew from postcolonial theory (scholar Homi Bhabha contributed to the dialogue), demonstrating Godzilla’s engagement with contemporary critical thought. In addition to such exhibits, Godzilla galvanized public dialogue by addressing real-world events: for example, the group framed discussions around the legacy of the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin (a Chinese American man killed in a hate crime) and the wave of anti-Asian sentiment in the early 1990s. Members organized open forums and spoken word events, and in the late 1990s, a West Coast chapter “Godzilla West” was formed, indicating the network’s national reach.

Godzilla also drew attention to the historical continuity of Asian American artistic activism. The collective often acknowledged its predecessors in Asian American arts organizing. Chief among these was New York’s own Basement Workshop, the first Asian American arts and media collective founded in 1970 during the grassroots community movements of that era. Many Godzilla members had ties to Basement Workshop or were inspired by its example of merging cultural work with activism. In 1998, the New Museum of Contemporary Art underscored this lineage by featuring an installation titled “From Basement to Godzilla” in its Urban Encounters exhibition, literally tracing the trajectory from the 1970s pioneers to the 1990s generation. This institutional recognition of Godzilla’s role was itself a cultural milestone: it meant that mainstream curators were finally taking note of the Asian American art movement as an important force. Lucy Lippard, a prominent critic, lauded the 2021 anthology Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001 as “an extraordinary compendium” of the collective’s letters, ephemera, and essays that doubles as a chronicle of evolving Asian American identity. She noted that reading it “is a reminder that community building is itself a form of resistance,” emphasizing that Godzilla’s model of artist-organizing was as significant as any individual artwork.

By 2001, Godzilla as an active network gradually dissolved, partly as many members advanced into prominent careers and partly due to the natural life cycle of activist groups. However, its legacy endures strongly in multiple ways. First, the individual successes of its alumni can be directly linked to the doors Godzilla helped pry open. Artists who were once “emerging” in Godzilla’s mailing list or group shows became exhibitors in the Whitney Biennial, Venice Biennale, and major gallery circuits by the 2000s. Curators like Margo Machida and the late Karin Higa (a early Godzilla participant who became a curator at the Japanese American National Museum) went on to shape academic and museum narratives about Asian American art. Secondly, Godzilla’s archival record, the documents of its meetings, protests, and publications, has become a valuable scholarly resource. The publication of the Godzilla: 1990–2001 anthology (edited by Howie Chen in 2021) has ensured that new generations can learn from its strategies and debates. This is especially pertinent in the present day, as renewed waves of anti-Asian racism (for instance, the post-2020 surge in hate crimes) have prompted Asian American artists to organize once again, often citing the 1990s activism of Godzilla as inspiration. Finally, Godzilla significantly influenced subsequent organizations and networks. Its pan-Asian approach prefigured groups like the Asian American Women Artists Alliance and the Diasporic Asian Art Network (DAAN) in the 2000s, which operate nationally among artists and art scholars. In essence, Godzilla helped demonstrate that Asian American artists could collectively assert their presence in the American art narrative, not as a marginal add-on, but as active shapers of contemporary art and its discourses. Its name, once a witty provocation, is now enshrined in art history as a symbol of how a “monster” network of dedicated artists can challenge and transform institutional norms.

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed the flowering of a distinct Filipino American arts and culture movement, as Filipino Americans, a growing segment of the Asian Pacific diaspora due to post-1965 immigration, began to organize cultural institutions and creative projects that affirmed their unique identity. Earlier in the 20th century, Filipino Americans had engaged in labor and civil rights struggles (notably the farmworker movement led by Larry Itliong and others), and individual artists and writers were present in the Asian American movement of the 1970s. However, it was in the 1980s that a cohesive Filipino American artistic voice gained momentum, fueled by a younger generation coming of age and a desire to bridge Filipino heritage with American life. This movement did not coalesce around a single organization, but rather through a network of artists, collectives, festivals, and community arts groups across the country. Its centers of activity were often in cities with large Filipino populations, such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Seattle, and its scope encompassed visual arts, theater, dance, music, and literature.

A pivotal figure in framing a Filipino American art historical consciousness was the late artist and educator Carlos Villa (1936–2013). Villa, a San Francisco native, had been active in the 1960s New York art scene but returned to San Francisco in 1969, inspired by the Third World liberation movements and the burgeoning ethnic studies programs on the West Coast. By the 1970s, as a professor at the San Francisco Art Institute, Villa began incorporating non-Western art forms and multicultural perspectives into his work, well before multiculturalism became a buzzword. He encouraged students to explore their own ethnic identities in art. According to artist Jenifer K. Wofford, who was one of Villa’s students, “Carlos was the first person to start talking about the importance of Filipino-American art history… All of a sudden I could see myself reflected in work and ideas by other Filipino-American artists. That had never happened before”. This quote highlights how groundbreaking Villa’s perspective was, he insisted that Filipino American artists had a history and a place in the broader art canon at a time when they were nearly invisible. Villa’s own artworks from the 1970s–90s often drew on Filipino indigenous traditions (for example, his mixed-media performances using feathers, bones, and body prints evoked tribal rituals) and on the history of Filipino immigration. In the 1990s, he created a series of installations called “Doors” that symbolically recreated the tiny hotel rooms that Filipino immigrant laborers (the manong generation) lived in upon arrival, complete with references to the Panama hats they wore, a humble garment Villa elevated to icon status as a “badge” of the pioneer Filipino migrants. By merging personal and cultural memory with contemporary art, Villa laid intellectual groundwork for a Filipino American aesthetic that was self-aware and decolonizing in intent.

Alongside Villa, many other Filipino American artists and cultural workers emerged in the 1980s–90s. Visual artists like Pacita Abad, who incorporated Filipino textile motifs into her painting, and Manuel Ocampo, who gained international notoriety in the 1990s for his provocative paintings blending Catholic iconography and colonial critique, brought Filipino voices to the global art stage. In literature and performing arts, figures such as Jessica Hagedorn (whose 1990 novel Dogeaters and multimedia performances depicted the Philippines and its diaspora) and Nora Okja Keller (a Fil-Am theater artist in California) created new narratives. Theatre and dance groups also formed: for example, Ma-Yi Theater Company, founded in 1989 in New York, originally focused on Filipino American plays before expanding to Pan-Asian work; and Kularts, founded in 1985 in San Francisco by Alleluia Panis, centered on contemporary and tribal Filipino dance and music. On college campuses, students organized Pilipino Cultural Nights (PCNs), annual shows blending drama, traditional dance, and modern commentary, which by the 1980s had become popular forums for young Filipino Americans to artistically explore their identity and history (a phenomenon so widespread it has since been studied as a rite of passage in Fil-Am student communities). These grassroots and institutional efforts collectively formed a movement that asserted Filipino American identity in the arts as something distinct yet integral to Asian America.

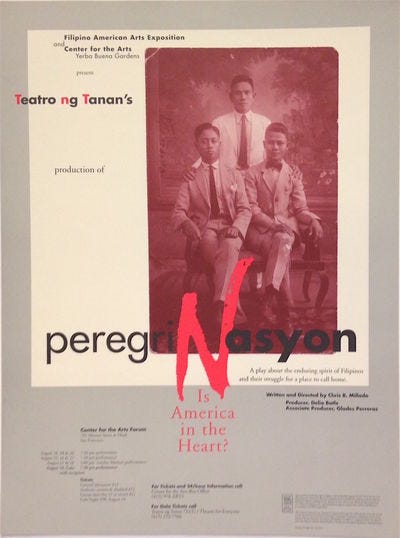

The Filipino American arts movement had a profound cultural impact, especially in fostering pride and solidarity within the community. During the 1980s, Filipino Americans often felt doubly marginalized, underrepresented in mainstream American culture and sometimes overshadowed within the broader Asian American umbrella (which historically had been led by East Asian narratives). The rise of Fil-Am arts organizations and events helped change that. In San Francisco, for example, Filipino American artists often collaborated with the Kearny Street Workshop and other APA groups but also carved out their own space. They organized “Ap-atong-a-baak” Filipino cultural street fairs and showcased Filipino music and dance at Chinatown festivals. The culmination of these efforts was the establishment of large public celebrations of Filipino culture. In Los Angeles, the Festival of Philippine Arts and Culture (FPAC) was launched in 1992 and became an annual event drawing thousands to celebrate Filipino heritage through performances, visual arts, and cuisine. In San Francisco, community leaders organized the Filipino American Arts Exposition (FAAE) in 1994, a milestone event that solidified the Fil-Am arts movement’s visibility. The inaugural FAAE event was a multi-week, multidisciplinary arts festival held at the brand-new Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, notably one of the first times a major American arts venue spotlighted Filipino American artists on such a scale. Curated by Carlos Villa and his colleagues, this 1994 Filipino American Arts Exposition featured visual art installations that paid homage to the manong immigrant generation and the legacy of the demolished I-Hotel (located just a few blocks away). The choice of Yerba Buena Gardens was symbolic: that area of downtown San Francisco had been part of the old “Manilatown” before redevelopment, so staging the Filipino Arts Exposition there represented a reclaiming of space through art. The exposition’s ambitious goal was to bring together the diverse Filipino communities of the Bay Area, from San Francisco to Daly City to Stockton, and invite the public to experience Filipino American art, music, dance, film, and history. It was a grassroots celebration that also doubled as an “artistic interrogation” of what it means to be Filipino in America, occurring at a time (the early 1990s) when the Philippines’ People Power revolution and subsequent waves of immigration had renewed Filipino American political consciousness.

The success of the 1994 exposition had lasting ripple effects. It provided the catalyst for subsequent and ongoing collaborations between Filipino American artists and major civic institutions, ensuring that Fil-Am cultural heritage gained a regular place in the city’s cultural calendar. In fact, the FAAE became an annual nonprofit organization that continues to produce the Pistahan Parade and Festival every August in San Francisco; an event now regarded as one of the largest annual Filipino American celebrations in the U.S., attracting tens of thousands of attendees. Through such festivals, as well as Filipino film festivals, art exhibits, and literary readings in the 1990s, the community fostered a sense of pride and unity. The arts movement also engaged with sociopolitical issues: many works from this era confronted themes like the legacy of Spanish and American colonialism in the Philippines, immigration and the search for “home,” and the daily experiences of the diaspora (from nursing and navy traditions to activism against the Marcos dictatorship). By expressing these narratives, Fil-Am artists helped educate both Filipino Americans and the broader public about Filipino history and identity, filling a gap in the American cultural mosaic.

The Filipino American arts and culture movement of the 1980s–90s left a durable legacy that can be seen in both community institutions and the trajectory of individual artists’ careers. On the institutional side, several organizations born in that era are still active today. The Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS), while founded in 1982 with an initial focus on history, also became a platform where cultural performances and arts were featured in its conferences and local chapters, reinforcing the importance of art in preserving history. The aforementioned FPAC festival in Los Angeles continues under the stewardship of FilAm ARTS, and San Francisco’s Pistahan (FAAE) festival endures as a vibrant hub of Fil-Am art, music, and community outreach. Additionally, physical spaces dedicated to Filipino American culture have emerged – for instance, the I-Hotel Manilatown Center, opened in 2005 on the site of the old I-Hotel, serves as a community gallery and performance space carrying forward the spirit of the 1970s activism into contemporary arts programming.

The movement succeeded in inserting Filipino American perspectives into the broader narrative of Asian American art. Exhibitions focusing on Filipino American artists have been mounted in museums, for example, “PAST FORWARD: Filipino American Artists” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1996, or the more recent retrospectives like “Carlos Villa: Worlds in Collision” at the Asian Art Museum and SFAC Gallery in 2022, which “proved that Filipino art history very much exists” and honored Villa’s role in creating a path for Fil-Am artists. The mentorship and community networks built in the 80s/90s are now bearing fruit in the form of mid-career Filipino American artists who were directly influenced by that pioneering generation. Villa’s former students and mentees, for example, include Michael Arcega, an installation artist whose work often satirizes colonial histories, and Paul Pfeiffer, who achieved international acclaim in contemporary art (and notably was part of a collective called Mail Order Brides with artists Eliza Barrios and Reanne Estrada, a trio that Villa himself introduced to each other). These artists, among others, represent the continuity of Fil-Am artistic innovation into the 2000s and beyond.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the 1980s–90s Fil-Am arts movement is the sense of cultural confidence and identity it instilled. What started as community poetry readings, punk rock shows at Mabuhay Gardens (a famous Filipino-run club), or campus cultural shows evolved into a recognized segment of American art. Filipino Americans today can point to a body of work, visual art, novels, plays, music, that reflects their experiences, much of it generated in that fertile period. By asserting “We are here, and our stories matter” through creative expression, the movement not only empowered those who participated in it but also laid a foundation for the current generation of Filipino American creatives. In the 2020s, Fil-Am artists and writers such as Joey Ayala, Catherine Ceniza Choy, Evelina Galang, or younger visual artists like Kristen Osorio continue to explore identity, often invoking the history and heroes of the 80s/90s movement as inspiration. The Filipino American arts & culture movement helped transform Filipino Americans from what Wofford described as a previously “invisible” presence in art into a visible, dynamic force with its own history and legacy.

Entering the 21st century, another significant facet of Asian American art emerged through the rise of South Asian American arts circuits. “South Asian American” generally refers to diasporic communities originating from the Indian subcontinent, primarily India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives, including those of South Asian descent born or raised in the United States. While individual South Asian artists and writers have been present in American arts since at least the mid-20th century, it was largely in the 2000s that South Asian American artists began forming networks, collectives, and recurring platforms to support their work and articulate their unique identities. This development coincided with the dramatic growth of South Asian immigration in the 1980s–90s, the coming-of-age of second-generation South Asian Americans, and the post-9/11 socio-political context that galvanized many in the community to assert their cultural presence in response to ignorance and bias. The term “arts circuits” suggests not one centralized movement but an interconnected web of festivals, organizations, exhibitions, and informal networks that together have brought South Asian American creativity to the fore.

Community Networks and Platforms: A key early node in this web was the founding of the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective (SAWCC) in 1997. SAWCC was initiated in New York City by artist-curator Jaishri Abichandani as a response to the lack of representation and support for South Asian women in the arts. Starting as a small gathering in Abichandani’s apartment, it quickly grew into a nonprofit organization providing both physical and virtual spaces for South Asian American female artists, writers, and creative professionals to share and showcase work. By 2000, SAWCC had an online listserv of over 500 members, and throughout the 2000s it organized monthly salons, annual exhibitions, open mic nights, and panels addressing themes of gender, cultural heritage, and racism. SAWCC’s programming, which highlighted visual artists like Chitra Ganesh and Swati Khurana, and writers like Jhumpa Lahiri (before she became a Pulitzer Prize winner), was instrumental in building a community of practice among South Asian American artists and in asserting that South Asian narratives (particularly women’s perspectives) belonged in the broader discussion of American art. SAWCC also forged alliances with other arts entities (e.g. it collaborated with Asian American Writers’ Workshop and 3rd I South Asian film society), thereby situating South Asian artists within the broader Asian American cultural coalition while still voicing distinct concerns (for instance, addressing Islamophobia or the experiences of diaspora Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus post-9/11).

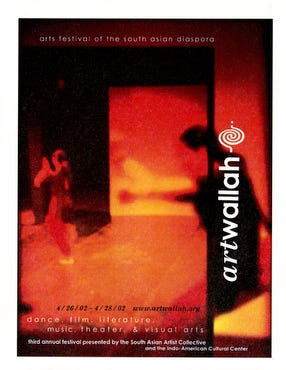

On the West Coast, similar impulses led to the creation of ArtWallah in Los Angeles. ArtWallah (from “art-wallah,” implying a person who does art) was founded in 1998 by a collective of young South Asian Americans who dreamed of an annual festival to “make ourselves and our work…visible in America” and to express “the vastness of the South Asian diasporic experience.”. The first ArtWallah Festival took place in 2002 and became a yearly multidisciplinary arts festival, featuring music, dance, theater, literature, film, visual arts, spoken word, and even stand-up comedy by South Asian Americans. As described by co-founder Shilpa Agarwal, by sharing work with each other and then with the public, the artists were “voicing who we were as people in this society… with roots in another country”, claiming space in America while honoring their heritage. ArtWallah’s impact grew as it partnered with local arts institutions (like the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center in LA) and featured performers both local and national. Notably, ArtWallah carved out a supportive environment for experimentation: artists from different disciplines would collaborate, fusing, say, spoken word poetry with classical Kathak dance or rock music with Bollywood influences. This cross-genre synergy mirrored the hybrid identities of the diaspora itself. By its 20th anniversary in 2018, ArtWallah had become a beloved community tradition in Southern California, demonstrating the power of a grassroots circuit to nurture emerging talents and culturally enrich the larger community.

In addition to SAWCC and ArtWallah, the 2000s saw an expansion of South Asian film festivals (such as 3rd i in San Francisco and NYU’s MIAAC film festival), literary networks (the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA) began collecting stories in 2008), and campus organizations (e.g. national South Asian student associations hosting arts showcases). Collectively, these circuits offered South Asian Americans avenues to celebrate and interrogate their dual identities at a time when external events – from the profiling of South Asians as “terrorist” threats after 9/11 to the explosion of Bollywood’s global popularity, made cultural representation both politically urgent and ripe for creative exploration.

South Asian American artists in the 2000s–present have engaged with a range of themes that reflect their complex identities. Common motifs include the idea of home and belonging, migration and displacement, the inheritance of partition and colonial histories, religious identity, gender and sexuality within South Asian cultures, and the negotiation of stereotypes (from Apu-like caricatures to model minority myths). A generation of visual artists began to make waves in contemporary art by infusing these themes into cutting-edge art practices. For instance, Shahzia Sikander, originally from Pakistan, pioneered a neo-Mughal painting style in the 1990s and by the 2000s her work, deconstructing Islamic and Hindu iconography, gained widespread acclaim, establishing her as a prominent figure in contemporary art (and influencing many Asian American artists on intercultural aesthetics). Rina Banerjee, an Indian American artist, creates fantastical sculptures out of South Asian materials like sari fabric and bindi pigments to comment on globalization and identity; Naeem Mohaiemen, of Bangladeshi origin, uses film and installation to revisit postcolonial political histories. By the 2010s, a critical mass of such artists led mainstream art institutions to take notice of the South Asian American experience as an important part of American art. A landmark moment was the exhibition “Fatal Love: South Asian American Art Now” at the Queens Museum of Art in 2005. Fatal Love was groundbreaking as the first major group exhibition in a U.S. museum dedicated specifically to contemporary South Asian American artists. Co-curated by Jaishri Abichandani (SAWCC’s founder) and others, the show featured artists like Shazia Sikander, Chitra Ganesh, and Alia Mamdouh, and explicitly addressed the climate after September 11, 2001, when South Asian Americans (Sikhs, Muslims, and others) faced intense scrutiny and hate crimes. The exhibited works tackled issues of surveillance, profiling, and the resilience of the community. Fatal Love not only made visible an artistic community that had been growing since SAWCC’s inception in 1997, but also asserted that South Asian Americans had “a strong presence in the New York art world” that deserved institutional support and national dialogue.

Following Fatal Love, South Asian diaspora art only gained in prominence. The Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center and Asia Society (two significant cultural institutions) both launched initiatives focusing on this field. In 2017, Asia Society in New York mounted “Lucid Dreams and Distant Visions: South Asian Art in the Diaspora,” showcasing 19 contemporary artists of South Asian descent who live and work in the U.S.. The exhibition noted that these artists, spanning four decades of activity, collectively have made a “significant impact on the development of contemporary art in the United States,” while exploring issues of home, migration, race, and memory. The roster included artists across generations, from veteran printmaker Zarina Hashmi, who distilled themes of exile in minimalist maps, to younger multimedia artists like Mequitta Ahuja and Baseera Khan. The same week, a symposium titled “Fatal Love: Where Are We Now?” was convened (at Asia Society and Queens Museum) to assess the state of South Asian American art after another decade of growth. There was recognition that while the community of South Asian artists had expanded and diversified, challenges remained, such as the relative scarcity of South Asian curators in major museums and the need for more national platforms to connect artists beyond local scenes. Nonetheless, social media and globalization have allowed South Asian American artists to connect with peers internationally (many operate between the U.S. and South Asia or other diaspora hubs like London or Toronto). Thus, the “arts circuits” today are truly transnational, blurring the line between “American” and “South Asian” art in productive ways.

The South Asian American arts circuits of the 2000s–present are still unfolding, but certain legacies are already evident. For one, these networks have firmly inserted South Asian stories into the American cultural tapestry. Twenty-five years ago, a South Asian character on TV or a contemporary Indian diasporic artist in a museum was a rarity; today, the influence ranges from Hollywood (witness the success of South Asian directors like Mindy Kaling or Aziz Ansari) to literary circles (Jhumpa Lahiri, Salman Rushdie, etc.) to fine arts. Pioneering curators such as Deepali Dewan in Canada and Iftikhar Dadi in the U.S. (who co-curated Lines of Control on partitions) have also contributed scholarly frameworks that tie South Asian American art into global art history. The community-driven approach, festivals like ArtWallah or collectives like SAWCC, has ensured a pipeline for new talent and a supportive environment where artists can explore themes like hybridity or social justice. Many artists who gained early exposure through these circuits have progressed to mainstream recognition. For example, Shahzia Sikander received a MacArthur “Genius” grant in 2006, Hari Kondabolu (a comedian) used the stage to challenge pop culture representations (like Apu from The Simpsons), and visual artist Anila Quayyum Agha won international art prizes for installations that reflect Islamic architectural art in a contemporary feminist context (she was featured in the 2017 Asia Society diaspora show).

The concept of what constitutes “American art” has broadened as a result of these movements. Major American museums like the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Whitney have begun to collect works by South Asian American artists, recognizing their place in the national story. For instance, SAAM’s collection now includes pieces by artists of Indian and Pakistani descent, signaling institutional validation. At the same time, South Asian American artists often operate in multiple contexts, participating in Asian American exhibitions, South Asian diaspora events, and general contemporary art venues, thus breaking down siloed categories. The circuits that once had to operate on the margins (community centers, niche festivals) have, in some cases, influenced the center.

As we look at the ongoing trajectory, one can say that South Asian American arts circuits have matured from a fledgling subculture into a dynamic, interconnected presence that continues to evolve. They emphasize dialogues across generations, pairing established and emerging artists, and maintain a transnational mindset, with ideas flowing back and forth between South Asia and the diaspora. In recent years, topics like the LGBTQ experience in South Asian communities, or the caste and colorism issues, have been bravely taken up by diaspora artists, showing the continuing growth in subject matter. The legacy of the 2000s–present circuits will likely be measured by how successfully they cultivate the next generation of artists and thinkers. Given the robust platforms already in place (from New York’s SAWCC and Brown Girls Webseries to Houston’s Shunya Theater or Chicago’s Silent Rhythm Ensemble), the outlook is one of increasing visibility and impact. As one assessment succinctly put it, for immigrants and children of South Asia, seeing an exhibit of South Asian American art can be “no less than a love letter to you”, a validation of belonging. These circuits have written many such love letters, asserting that South Asian Americans are not outsiders looking in at American culture, but active creators and authors of it.

Examining these movements side by side, Kearny Street Workshop, Godzilla, the Filipino American arts surge, and South Asian American arts circuits, reveals a rich tapestry of Asian American artistic activism that spans geography, generations, and ethnic specificities. Each movement arose in response to a distinct historical moment and set of challenges, yet all share underlying commonalities in their goals and outcomes. Collectively, they chronicle the evolution of Asian American art from the early 1970s community grassroots to the global, digitally-connected networks of today.

One common thread is the drive for self-representation and agency. All four movements responded to a sense of marginalization by creating their own spaces to tell their stories. In the 1970s, KSW’s founders literally built a workshop because mainstream art institutions had no room for Asian Americans; in the 1990s, Godzilla’s members organized as a coalition to demand visibility in galleries and museums that ignored them; Filipino American artists in the 80s/90s and South Asian American artists in the 2000s similarly established festivals and collectives when they did not see themselves in the cultural mainstream. By asserting “we will create our own platforms,” these artists transformed their outsider status into empowered action. This community-building ethos, the idea that artists can achieve more together, especially when navigating issues of race and representation, is itself a form of cultural resistance and resilience. It echoes across time: the solidarity of KSW’s Chinatown activists painting a mural for the I-Hotel is not unlike the solidarity of South Asian poets and dancers convening an ArtWallah showcase, both are about carving out a place where their community’s narrative is front and center.

Another shared aspect is the interplay of art and politics/activism. These movements consistently leveraged art as a means of activism or social commentary. KSW directly merged with the Asian American civil rights movement, producing protest art and fostering activists; Godzilla engaged in institutional critique and took on issues like anti-Asian violence and censorship; Filipino American artists addressed post-colonial identity and immigrant rights (even the choice to celebrate cultural heritage publicly was a political statement against erasure); and South Asian American artists confronted post-9/11 racism and reimagined colonial histories. In doing so, they expanded the definition of American art to include social issues and the lived realities of minority communities. The idea that “art made by people of color is inherently political” (as Jason Bayani of KSW put it) resonates through all these cases. Yet, the art was not narrowly propagandistic; it was often deeply personal, imaginative, and formally innovative. For example, the aesthetics ranged from the bold graphic posters of the 70s to the conceptual installations of Godzilla members, from the ritual-inflected performances of Carlos Villa to the digital multimedia of contemporary South Asian artists. Each movement contributed new aesthetics and techniques, enriching American art with diverse influences (be it Chinese calligraphy, Filipino tribal art, Indian miniature painting, etc.) while speaking to the conditions of diaspora life.

Differences among the movements highlight the diverse experiences within Asian America. Kearny Street Workshop and Godzilla were pan-Asian in composition, bringing together multiple ethnic Asian groups under one umbrella. This model fostered interracial solidarity and reflected a broader Asian American identity politics that emerged from the 1960s–90s. In contrast, the Filipino American and South Asian American movements were more ethnically specific, arising in part because those communities wanted to assert their particular cultural identities which they felt were overlooked even within the pan-Asian discourse. The Filipino American movement intersected with pan-Asian efforts (Filipinos were active in KSW and Godzilla too), but also followed a slightly different timeline, hitting its stride in the 80s/90s, a bit later than the East Asian–led 70s movement, due to different immigration patterns and socio-political contexts (e.g. many Filipino Americans are Catholic and carry a Spanish-influenced heritage, distinguishing their cultural expression). South Asian Americans, often not included in the term “Asian American” until more recently, largely built their own parallel circuits in the 2000s, though they have increasingly linked up with broader Asian Pacific American initiatives (e.g. AAPI umbrella organizations). Despite these differences, there has been cross-pollination: for instance, Godzilla’s pan-Asian membership did include South Asians, and KSW’s programs eventually included South and Southeast Asian artists as well. The comparative legacy is that Asian American art discourse has become more inclusive and pluralistic over time; moving from a perhaps Chinese/Japanese-dominated narrative in the early years to a panorama that now readily embraces Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, South Asian, Pacific Islander, and other voices under the AAPI arts umbrella. Each movement contributed to this widening of the lens, ensuring that “Asian American art” is not monolithic but richly varied.

Another difference is in structure and longevity. KSW, being an institution, offers an example of longevity and adaptation (50+ years and running), whereas Godzilla was a time-bound collective (roughly 11 years of activity) that intentionally dissolved as its mission was absorbed by the mainstream. The Filipino American and South Asian initiatives were/are more diffuse; not a single organization but multiple nodes, some of which (like festivals) recur annually, others (like short-term collectives) that formed and disbanded. This suggests that some efforts needed to institutionalize to survive (KSW becoming a nonprofit), while others benefited from remaining fluid and project-based (Godzilla never had a physical center or formal hierarchy, which allowed flexibility but also meant it sunset when it had run its course). In comparative terms, the institutionalization of Asian American arts has its pros and cons: a stable org like KSW can provide continuity and archival preservation (e.g. KSW’s archives at UCSB and its sustained mentorship via APAture), whereas ephemeral groups like Godzilla or pop-up festivals capture the energy of a moment and can spark change quickly but may leave fewer long-term structures. Notably, the impact of the ephemeral groups often leads to later institutional recognition or incorporation, for example, what Godzilla fought for in the 90s (museum inclusion) gradually happened in the 2000s and 2010s; what South Asian festivals did at a grassroots level eventually spurred big museums to host South Asian shows and conferences. Thus, both approaches were necessary in the ecosystem.

Finally, is their legacy and continuity. Each successive movement built on the successes and lessons of those before it. The Asian American movement of the 1970s (with KSW and Basement Workshop) laid the groundwork of community arts organizing and identity assertion that Godzilla’s generation referenced and took forward into the professional art world realm. Filipino American artists, active in those earlier movements, realized by the 80s that they could both work within pan-Asian spaces and also highlight their own narratives, in essence expanding the canvas of Asian American art. South Asian Americans, who in the 70s were a very small portion of the Asian American population, by the 2000s had the critical mass and inspiration (seeing how Chinese, Japanese, Filipino Americans had done it) to mobilize their own arts networks, while also aligning with the broader “people of color” and Asian American frameworks, especially in post-9/11 solidarity contexts. The movements are chapters of a larger story: one can trace a line from the I-Hotel mural painters of 1977 to the Desi slam poets of the 2000s; both, in their times, declared, “We will not be unseen.” Each chapter has made Asian American artists more visible and American art more inclusive.

The histories of Kearny Street Workshop, Godzilla, the Filipino American arts movement, and South Asian American arts circuits collectively illustrate how marginalized communities can transform the culture around them through sustained creative and organizational efforts. From community art classes and protest posters to avant-garde exhibitions and global diaspora collaborations, Asian American artists have used every tool at their disposal to express multifaceted identities and to demand space in the American cultural narrative. They have founded workshops and festivals, written letters and manifestos, danced in the streets and hung paintings in major museums – enabling dialogues that were previously silenced. The legacy of these movements is visible not only in archives, citations, or works of art, but in the very fact that a young Asian American artist today can take for granted the existence of mentors, galleries, and community support that did not exist half a century ago. They stand on the shoulders of those earlier trailblazers. And in a society still grappling with issues of representation and equity, the story of these movements serves as a powerful reminder that culture can be reclaimed and reinvented by those whom it has excluded. As Margo Machida wrote in 1990, America is not a “melting pot” but “a loose confederation of autonomous subgroups in dynamic interaction”, a description vividly borne out by these dynamic Asian American arts subcultures. Their interactions with each other and with the broader society have irrevocably changed the landscape of American art, making it more honest, diverse, and inclusive.

References:

Abichandani, Jaishri, et al., editors. Fatal Love: South Asian American Art Now. Queens Museum of Art, 2005.

Bayani, Jason. Quoted in Cabanatuan, Michael. How Kearny Street Workshop Created a Platform for Asian American Artists in the Bay Area. San Francisco Chronicle Datebook, 23 Oct. 2019, datebook.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/how-kearny-street-workshop-created-a-platform-for-asian-american-artists-in-the-bay-area.

Chen, Howie, editor. Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001. Primary Information, 2021.

Filipino American Arts Exposition (FAAE) – About FAAE. Pistahan Parade and Festival, Filipino American Arts Exposition, www.pistahan.net/faae. Accessed 17 Feb. 2025.

Gavino, Julianne, et al. Placemaking and Posters: The Imprint of Kearny Street Workshop at the I-Hotel. Visions and Voices of the I-Hotel: Urban Struggles, Community Mythologies and Creativity, Community Arts Perspectives (MICA), 2017, archived at web.archive.org/web/20180215023443/https://www.mica.edu/.../Visions_and_Voices_of_the_I-Hotel.html.

Hom, Nancy. Quoted in Kearny Street Workshop. UCSB Library, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives (CEMA), 2008, www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections/cema/kearny.

Lippard, Lucy. Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001. The Brooklyn Rail, Apr. 2022, brooklynrail.org/2022/04/art_books/Godzilla-Asian-American-Arts-Network-1990-2001.

Machida, Margo. Unsettled Visions: Contemporary Asian American Artists and the Social Imaginary. Duke University Press, 2008.

Manilatown’s I-Hotel & Kearny Street Workshop. Visions and Voices of the I-Hotel, interviews by Julianne Gavino, Maryland Institute College of Art, 2017.

Raphael, Michele. ArtWallah Festival Gives a Voice to South Asian Artists and Performers. LA Weekly, 31 May 2018, www.laweekly.com/artwallah-festival-gives-a-voice-to-south-asian-artists-and-performers/.

Tagle, Thea Quiray. After the I-Hotel: Material, Cultural, and Affective Geographies of Filipino San Francisco. 2015. University of California, San Diego, PhD dissertation.

South Asian Women’s Creative Collective. Wikipedia, updated 23 Jul. 2022, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Asian_Women%27s_Creative_Collective.

Uncle Carlos: Carlos Villa’s Legacy. SF Standard, 24 June 2022, sfstandard.com/arts-culture/erasing-erasure-two-historic-exhibits-cement-the-legacy-of-late-filipino-artist-carlos-villa/.

University of California, Santa Barbara. Guide to the Kearny Street Workshop Archives, CEMA 33. Online Archive of California, 2008, oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt62903498/.

This is impressive scholarship; many thanks for that. But this is some powerful nostalgia for me, and has completely distracted me. I have lived in SF since before the International Hotel came down, before Dan White assassinated Harvey Milk and George Moscone, and just before the Golden Dragon massacre (I attended the entire trial of Melvin Yu, the youth gang member who wielded the machine gun that he blasted inside the restaurant). Warren Hinckle said of these last years of the 70's, that they were "the most emotionally devastating years in San Francisco’s fabulously spotted history." And the Mabuhay Club on Broadway, just down the street from the blinking anatomy of Carol Doda, was the scene of midnight madness on a 4th of July that provided the drama for one of my earliest trial victories, one that makes me boastful, a victory that still astonishes me. Like I said, this is some powerful nostalgia for me. Indulge me just a little further, remembering:

At the Rainbow Tunnel

1 December 1976

5:05 p.m.

On the eastern horizon

The full moon dawns

Over the Berkeley hills

And when I look back

I see the sun

In glistening destiny

Beginning to set

In the west

Just so they were

It is said

At the creation

And so they will be

At the twilight of time