Gluck, born Hannah Gluckstein in 1895, remains one of the most defiant and enigmatic figures in twentieth-century British art. Born into wealth as a member of the Gluckstein family behind the J. Lyons & Co. food empire, Gluck was afforded a degree of financial and personal independence that enabled a radical break from social expectations. But what distinguishes Gluck most profoundly is not only the quality of their paintings, meticulously executed portraits and still lifes, but the singularity of their personal and artistic identity. Gluck rejected traditional gender roles, names, and conventions. They demanded to be known solely as “Gluck,” a mononym without prefix or suffix, and refused all attempts to classify their work within movements or schools. Gender-nonconforming, masculine-presenting, and unapologetically lesbian, Gluck’s very existence was an affront to the binary norms of the early twentieth century, and their work has since been reclaimed as a cornerstone in the history of queer art.

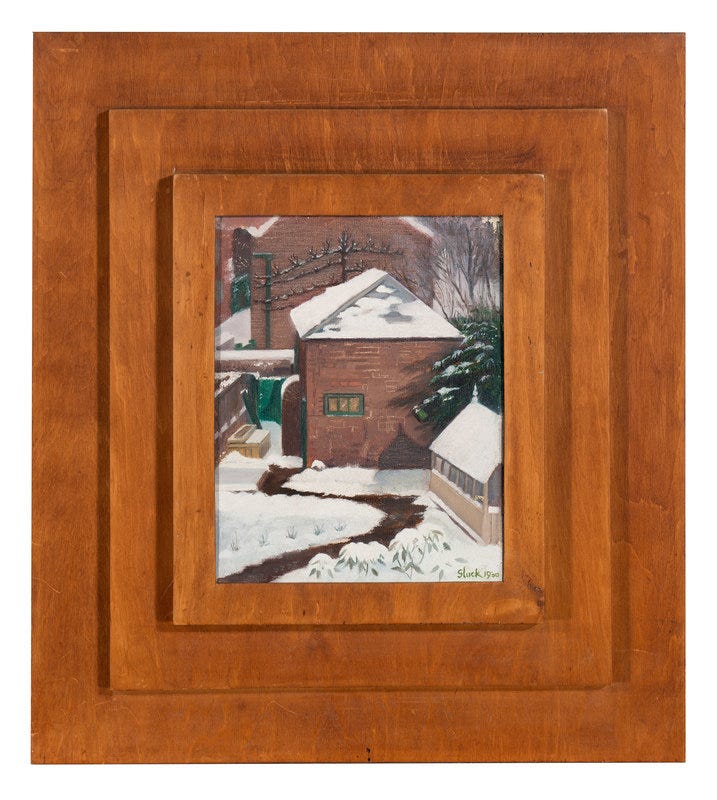

From the 1920s onward, Gluck made a conscious decision to eliminate all gendered references to their name, choosing instead to identify publicly and privately with only the name “Gluck.” This demand was not a superficial affectation but a radical political stance. Gluck insisted that exhibition catalogues, press releases, and all correspondence exclude any gendered honorifics. The artist’s gender nonconformity extended beyond the name: Gluck wore traditionally masculine clothing, had their hair cut short, and conducted themselves socially as male-coded, though they never publicly identified as transgender (Seymour 24–26). Their self-presentation blurred lines between lesbian identity and gender-nonbinary expression decades before either of those terms had wide cultural currency. Art historian Amy de la Haye notes that “Gluck’s stylistic self-determination was inseparable from their creative identity and artistic control” (123), pointing to their tailored suits and insistence on designing a custom frame, the so-called “Gluck frame”, to house their paintings. This frame, with its distinctive three-tiered structure, became a visual metaphor for Gluck’s demand to exist entirely on their own terms: aesthetically, professionally, and personally.

One of the most defining relationships in Gluck’s life was with Nesta Obermer, a married upper-class woman whose beauty and presence became central to Gluck’s artistic expression. Their romance was not merely personal, it was rendered visible through one of Gluck’s most iconic paintings, Medallion (1936), which depicts Gluck and Obermer in profile, faces nearly touching, their expressions serene and connected by shared light. Gluck referred to it as the “YouWe” picture, a name which underscores the intimacy and collapse of separate identity into shared emotional space (Gluck qtd. in Hall 84). Painted in luminous tones, the work eschews allegory or symbolic metaphor often found in depictions of queer love; instead, it presents two women in full, unapologetic presence. Scholar Emmanuel Cooper has called Medallion “a declaration of love, a record of intimacy and emotional intensity that dares to speak the unspeakable” (59). Unlike other contemporary works that coded queer relationships through mythological or exoticized frameworks, Medallion offers a stark, proud image of lesbian love. Notably, it was exhibited without explanation or obfuscation; a bold act of resistance during a period when same-sex desire between women was often erased or relegated to the shadows.

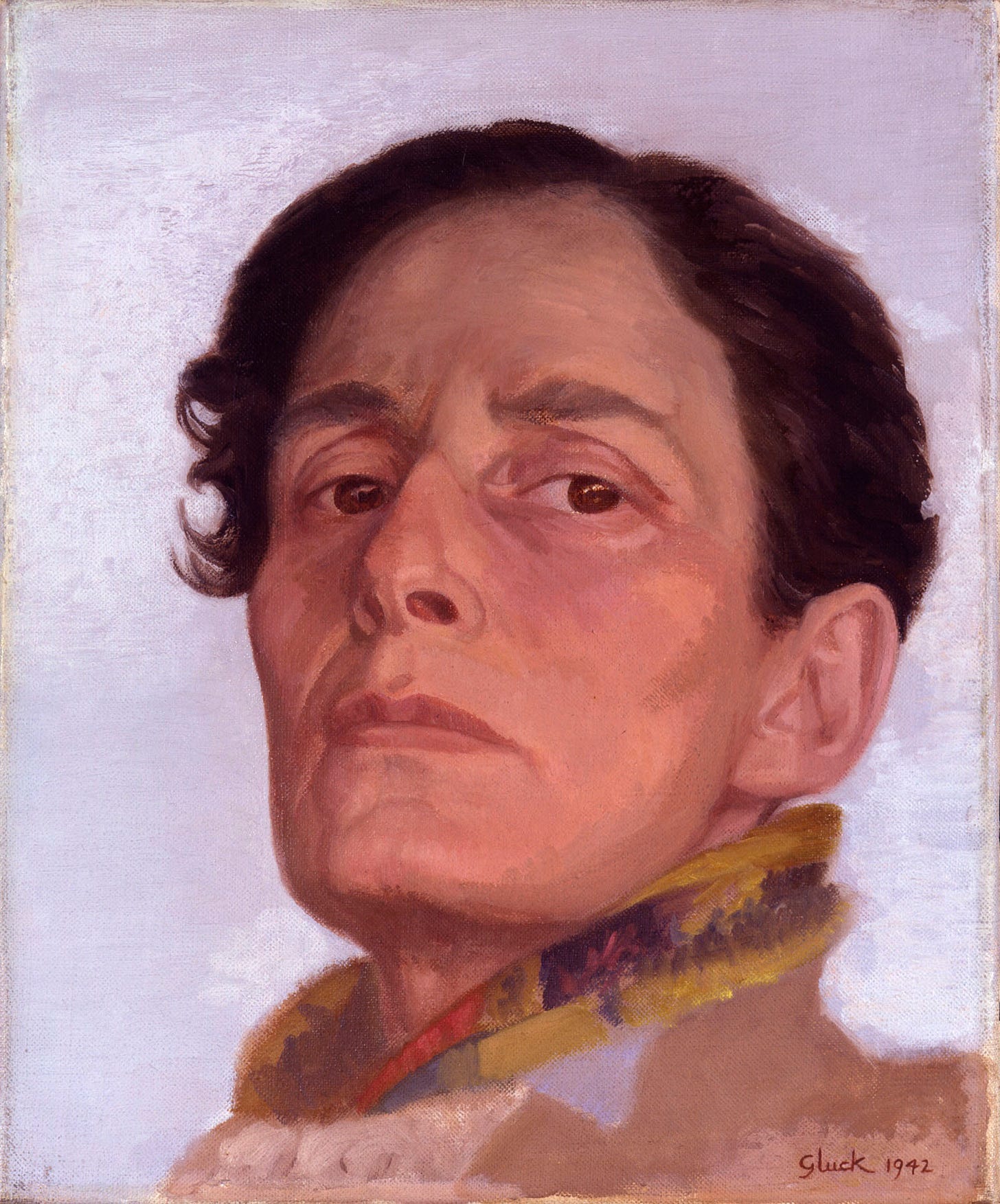

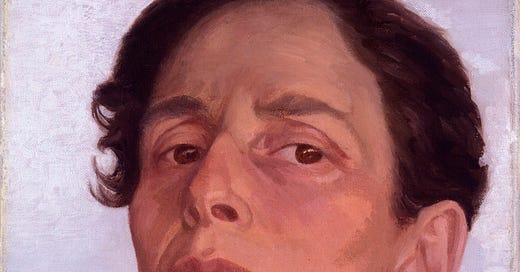

Portraiture remained central to Gluck’s practice, and perhaps no work exemplifies their ethos more than their 1942 Self-Portrait. The painting presents Gluck wearing an overcoat and collared shirt, their hair slicked back, and their gaze direct and unflinching. There is no trace of femininity in the traditional sense; instead, the image projects strength, defiance, and autonomy. Whitney Chadwick observes that this portrait resists the traditional objectifying gaze: “The portrait’s gaze is unflinching, denying the objectification of the viewer and presenting a subject who resists classification” (204). Gluck’s self-portraits, like their insistence on the custom Gluck frame, operate as assertions of complete visual and social self-determination. Unlike many female artists of the time who contended with the double marginalization of being both women and creators, Gluck refused to engage with gendered expectations of either beauty or vulnerability. Their self-representation aligned more closely with that of male painters asserting their mastery of craft and control over their public image.

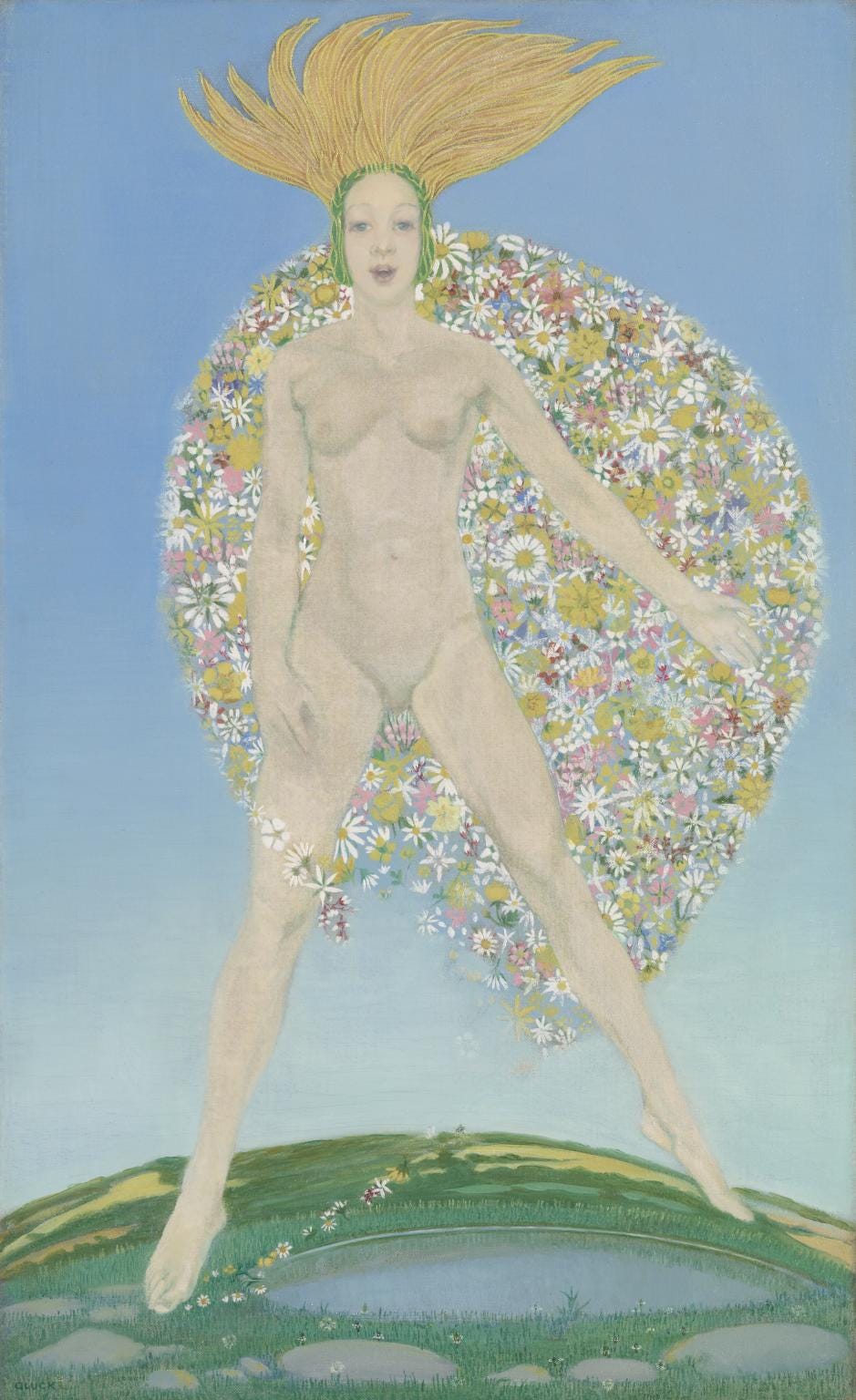

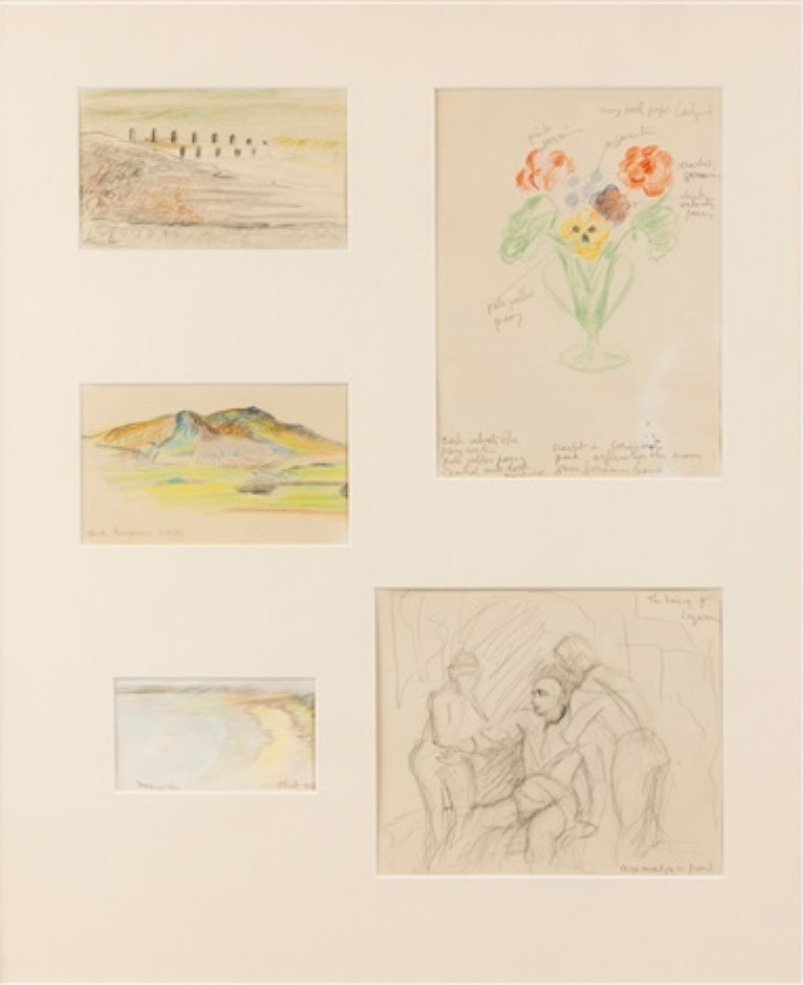

Alongside these powerful portraits, Gluck also produced a remarkable series of floral still lifes. Although at first glance these may seem to exist within a more “feminine” artistic tradition, Gluck’s treatment of florals is anything but decorative or domestic. Works such as Lilac and Guelder Rose (1932), Nature Morte (1937) and The Devil’s Alter (1932) display botanical precision alongside sensual intensity. Each petal and stem is rendered with reverence, yet there is an erotic tension and boldness in the composition that subverts the genteel history of the floral still life. Laura Doan has argued that Gluck’s flower paintings represent “a floral eroticism; a queering of the still life that resists domestication” (146). The still life, long dismissed in academic art circles as trivial or feminized, is here reclaimed and reinvested with power and complexity. Much like the artist themself, the flowers in Gluck’s paintings defy reduction to conventional categories. They are sensual without being sentimental, assertive without being aggressive. This subversion of genre was another way in which Gluck infused their work with a queer aesthetic, challenging not just gender norms, but hierarchies of artistic value.

Despite the early acclaim Gluck received in the interwar period, their later career was marked by increasing withdrawal. Disillusioned with the changing tides of the art world, especially the rise of abstraction and what they perceived as a decline in artistic standards, Gluck became reclusive after World War II. They remained exacting in all things, especially in how their past works were shown or reproduced. Gluck continued to live and paint in a cottage in Sussex, often isolated but never passive. Even in obscurity, they retained complete control over their image and their legacy.

It was not until the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries that scholars and curators began to reevaluate Gluck’s contributions. The growing field of queer art history, with its focus on reclaiming overlooked LGBTQ figures, has placed Gluck at the center of discussions about gender nonconformity and lesbian representation in visual culture. Curator Stephen Calloway wrote in the definitive 2017 exhibition Gluck: Art and Identity that Gluck was “above all else, an artist of uncompromising identity. In every stroke, every frame, every gaze, we see the assertion: ‘I exist. I am not what you say I am’” (311). This legacy resonates deeply with contemporary audiences, especially those navigating fluid or nonbinary identities. Although the language to describe Gluck’s identity has evolved, their defiance of binary categorization remains as vital today as it was radical then.

In reclaiming Gluck as a queer icon, we do not impose modern identity labels retroactively, but rather acknowledge the artist’s lifelong refusal to conform to heteronormative or gendered expectations. Their insistence on control, of name, image, frame, and form, was itself a declaration of independence. Through their portraits, florals, and unyielding sense of self, Gluck forged a space in British art that was defiantly their own. Today, that space continues to expand, as new generations look to Gluck not only for artistic inspiration but for the courage to live and create beyond the margins.

References:

Calloway, Stephen. Gluck: Art and Identity. Yale University Press, 2017.

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. 5th ed., Thames & Hudson, 2012.

Cooper, Emmanuel. The Sexual Perspective: Homosexuality and Art in the Last 100 Years in the West. Routledge, 1994.

de la Haye, Amy. Gluck’s Clothing and the Visual Politics of Nonconformity. A Queer Little History of Art, edited by Alex Pilcher, Tate Publishing, 2017, pp. 120–129.

Doan, Laura. Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture. Columbia University Press, 2001.

Donoghue, Emma. Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature. Vintage, 2011.

Hall, Donald. Queer Theories. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Seymour, Claire. Gluck and the Art of Androgyny. Oxford Art Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, 2009, pp. 22–38.

I like the flower studies^^

I have to start by saying one of my X’s name was Glucksman and they called him Lucky Glucky. So when this popped up in my phone I nearly had a heart attack. I thought he was on Substack. Like oh no!