Morocco’s cultural and architectural heritage is exceptionally diverse, reflecting a long history of varied influences. Across millennia, the region absorbed elements from prehistoric civilizations, ancient Mediterranean colonizers, indigenous Berber (Amazigh) traditions, the Arab-Islamic world, and later European powers. This rich tapestry of influences produced an architectural legacy that spans Roman-era ruins and medieval Islamic monuments to vernacular earthen fortresses and 20th-century colonial designs. Hallmarks of Moroccan architecture, such as the horseshoe arch, serene riad courtyard gardens, and intricate geometric ornament in wood, plaster (stucco), and tile, emerged through a synthesis of indigenous North African forms with inspirations from al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) and the broader Middle East. The result is a unique style with recognizable motifs and techniques developed over more than a thousand years.

Archaeological evidence shows that the region of present-day Morocco has been inhabited since prehistoric times. Recent discoveries at Jebel Irhoud revealed fossil remains of early Homo sapiens over 300,000 years old, underscoring North Africa’s role in the deep human past. By the Neolithic period, various prehistoric communities left their mark in the form of rock art, megalithic tombs, and early settlements, although these fall outside the scope of architectural monuments in the classical sense. These early inhabitants nonetheless established a long continuity of human presence on the land that later civilizations would build upon.

By the first millennium B.C.E., Morocco’s shores drew the interest of seafaring civilizations from the eastern Mediterranean. Phoenician traders established coastal outposts such as Lixus (near modern Larache) by the 7th century BCE. Lixus, and later settlements like Tingis (Tangier) and Mogador (Essaouira), served as trading colonies linking North Africa to the Phoenician and Carthaginian networks. The ancient city of Lixus grew under Carthaginian influence and, after Carthage’s fall in 146 BCE, came under Roman control. It became an imperial Roman colony (reaching its peak during Emperor Claudius’s reign, 41–54 CE) and illustrates the early blend of Punic (Phoenician/Carthaginian) and Roman cultural layers along Morocco’s coast.

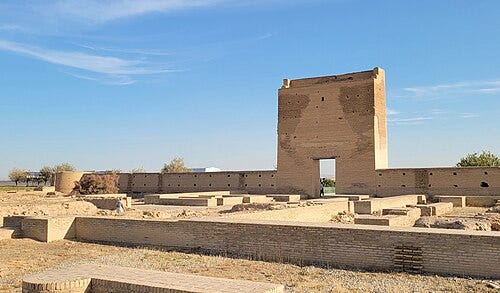

From the first century B.C.E. to the third century C.E., northern Morocco formed part of the Roman Empire’s province of Mauretania Tingitana. The archaeological site of Volubilis (near Meknes) offers the clearest window into this era. Volubilis began as the capital of the indigenous Mauritanian kingdom around the 3rd century BCE and later developed into a prosperous Roman city after the Mauretanian rulers were integrated into the empire. At its height, Volubilis was endowed with all the hallmarks of Roman urbanism: a regular grid plan (the decumanus and cardo streets) and monumental public buildings, including a forum, a basilica for civic administration, a triumphal arch, temples, bath complexes, and ornate townhouses with mosaic floors. Enclosed by a 2.3 km circuit of walls, the city commanded a fertile agricultural hinterland and stood as a distant but vital outpost of Roman civilization on Africa’s Atlantic fringe. The ruins of Volubilis, its Capitolium, triumphal arch of Caracalla, and dozens of mosaic-adorned villas, represent some of the richest archaeological remains of that period in North Africa.

Roman influence on Morocco was not limited to Volubilis. Other sites like Sala Colonia (Chellah in Rabat) and Tingis (Tangier) also bear remnants of Roman town planning and architecture, though often overlaid by later periods. These cities facilitated cultural and technological transfer, bringing features like stone construction, the Latin language, and Roman law into the region. Yet Roman control was relatively short-lived. By the late 3rd century CE, as the Roman Empire’s western frontiers contracted, cities like Volubilis were left to local rule and gradually declined. Nonetheless, the legacy of this “African Rome” endured: the very name Walili (Volubilis) lived on in local memory, and impressively, the site’s forum, basilicas, arches, and city grid remained visible to inspire later generations.

Importantly, Volubilis also provides a bridge to Morocco’s early Islamic history. After the collapse of Roman authority, the region saw a few centuries of political fragmentation (sometimes termed a “Dark Age” in North Africa). But when the Arab-Islamic conquest reached Morocco in the 7th–8th centuries, Volubilis found a new role. In 789 CE, the city became the initial seat of the region’s first Islamic dynasty under Idris I. For a brief period, Walila (Volubilis) was repurposed as the capital of Idris I’s nascent kingdom. Although Idris I’s son would soon found a fresh capital (Fez), the choice of Volubilis underscores continuity with the ancient past. In fact, Idris I’s mausoleum is in the nearby town of Moulay Idris Zerhoun, making Volubilis a unique site that encapsulates over ten centuries of occupation from the prehistory through Roman and into Islamic times. The confluence of Libyco-Berber, Roman, Christian, and early Islamic material at Volubilis stands as “an outstanding example of an archaeological and architectural complex” bearing witness to Morocco’s multicultural foundations.

Thus, by the end of antiquity, Morocco had inherited a set of urban and architectural traditions: fortified towns, monuments in stone, and a concept of the city as a political and economic center. The coming of Islam would both preserve some of these ancient legacies (for example, reusing Roman ruins or city-sites) and transform the architectural landscape with new forms and purposes. The stage was set for the next major era in Moroccan architecture; the Islamic conquest and the emergence of indigenous Muslim dynasties that would craft a distinctly Moroccan-Islamic architectural style atop these early foundations.

The Arab-Islamic arrival in the late 7th century brought a new religious and cultural paradigm that profoundly influenced Morocco’s urban development and architecture. Early Islamic historians note that Uqba ibn Nafi reached the Atlantic coast by 682 CE, but lasting Muslim rule was not consolidated until the early 8th century under the Umayyad governors of Ifriqiya (Tunisia). As centralized Umayyad control waned, autonomous local states began to form. The most significant was established by Idris I, a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad who fled the Abbasid East and arrived in Morocco around 788 CE. With local Berber support, Idris I founded the Idrisid dynasty (788–974), marking the start of Morocco’s first native Islamic state.

Idris I initially settled at Volubilis (Walila), but it was his son, Idris II, who in 808 CE founded the city that would become the spiritual and cultural heart of Morocco: Fez (Fès). Idris II established Madinat Fas on one bank of the Fez River and, according to tradition, invited refugees from Islamic Spain (al-Andalus) and Tunisia (Kairouan) to populate it. Across the river, a second settlement (al-‘Aliya) grew, largely populated by Kairouanese immigrants. These twin settlements, often called the Andalusian Quarter and the Kairouan Quarter, later merged to form Fez’s celebrated medina. The Idrisids’ role in Fez’s foundation is critical: it created a new urban nucleus that would endure as a center of religion, learning, and craftsmanship for over a millennium.

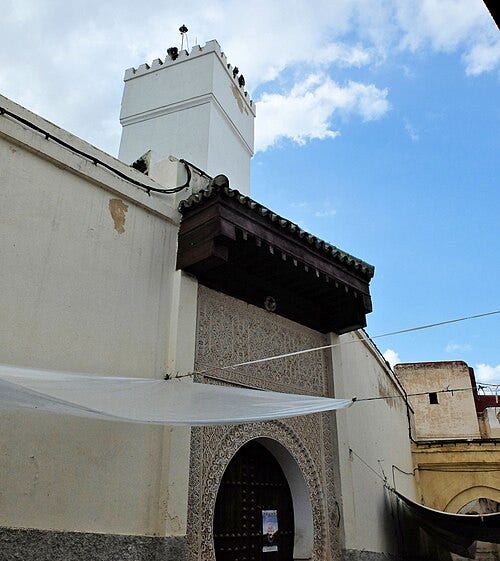

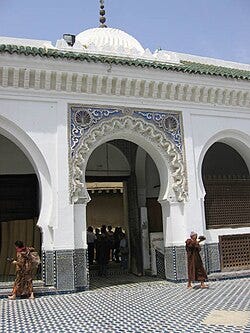

Fez under the Idrisids and subsequent dynasties exemplified early Islamic urbanism in Morocco. The medina (old city) developed as a dense maze of winding streets, crowded markets (souqs), residential quarters, and landmark monuments, all within a circuit of defensive walls. Notably, mosques and fountains became central architectural features under Islamic patronage. The Idrisids are credited with building some of the first mosques in Fez, such as the Mosque of the Sharifs (where Idris II himself was later buried, now the shrine of Moulay Idris) and the Al-Andalusiyyin Mosque (Andalusian Mosque) founded in 859 CE. Although these structures were later rebuilt or modified, their foundations signified the new faith’s imprint on the urban fabric. In 859 CE, a pious woman of Kairouan, Fatima al-Fihri, endowed the Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez, which grew into a major center of learning (often dubbed the oldest continuously operating university in the world). The Qarawiyyin’s early medieval structure, a classic hypostyle mosque with a courtyard, was continually expanded in later centuries, but its origin in the Idrisid period underlines the dynasty’s architectural legacy.

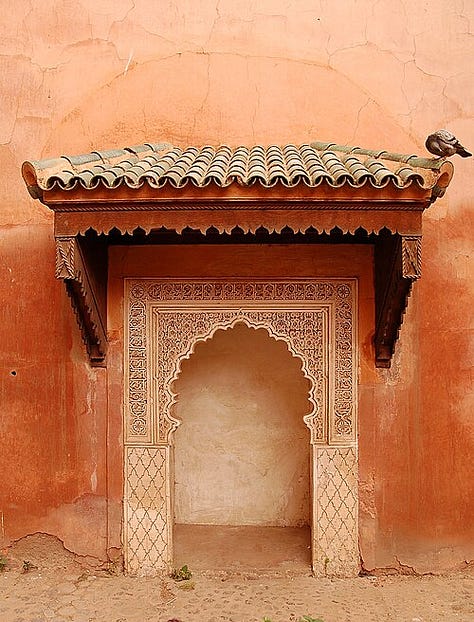

The medina of Fez still retains the imprint of these early centuries. It is characterized by a cellular urban layout, where residential cul-de-sacs lead off main market streets, and public fountains and baths dot the quarters. Many of the urban functions that define historic Moroccan cities, such as funduqs (caravanserais for merchants), hammams (bathhouses), and tanneries, were present in some form in early Fez. The Idrisids likely introduced or encouraged the use of horseshoe arches and simple floral or geometric motifs derived from Abbasid art, although the surviving examples in Fez today date mostly from later dynasties.

One of the Idrisids’ most enduring contributions was establishing Fez as a political and religious capital, which gave impetus to architectural patronage by later rulers. Even after the Idrisid dynasty faded in the 10th century, Fez remained prized; the city “preserves the memory of the capital founded by the Idrisid dynasty between 789 and 808 A.D.”. Its continuous development demonstrates an accumulation of styles over time. By the 11th century, the two original towns were enclosed together by new walls under the Almoravid dynasty, and in the 13th century the Marinids built Fez Jdid (New Fez) as a royal city adjacent to the old medina. Nonetheless, the core spatial arrangement of Fez’s medina, irregular street grids adapted to topography, inward-focused courtyard houses, and mixed-use neighborhoods each with a mosque, bath, bakery, and fountain, was an Idrisid foundation that persisted. The UNESCO World Heritage description of Fez notes that the city “constitutes an outstanding example of a medieval town created during the very first centuries of Islamisation of Morocco,” representing a formative period of Moroccan urban culture.

Beyond Fez, the Idrisids influenced other locales. They established or fortified towns such as Moulay Idris Zerhoun (which grew around Idris I’s tomb near Volubilis) and Chefschaouen (Chefchaouen) in the Rif Mountains, though little survives from that era in these towns’ architecture. The Idrisids’ zenith was relatively short-lived, later in the 10th century, they were eclipsed by the Fatimid and Cordoban caliphates’ influence, but they had set in motion the Arab-Islamic architectural vocabulary in Morocco: mosques with square minarets, enclosed medinas with souqs and city walls, and the integration of Andalusian stylistic elements brought by émigrés.

The Islamic conquest and Idrisid dynasty laid the groundwork for Morocco’s classical architectural heritage. They established new cities (preeminently Fez) and repurposed ancient ones like Volubilis, introduced Islamic forms like mosques and minarets into the built environment, and helped synthesize Berber and Arab urban traditions. The stage was now set for the great Berber empires, the Almoravids and Almohads, to unite Morocco and further develop its architectural tradition.

By the 11th century, Morocco saw the rise of powerful Amazigh (Berber) dynasties that not only unified the country after centuries of division but also launched imperial ventures across Northwest Africa and Iberia. Two successive Berber empires, the Almoravids (c. 1055–1147) and the Almohads (1147–1269), were especially pivotal in shaping the forms of Moroccan and Maghribi architecture. Their rule corresponds to one of the most formative stages of Moroccan and “Moorish” architecture, during which many of the archetypal structures, motifs, and techniques were either introduced or firmly established.

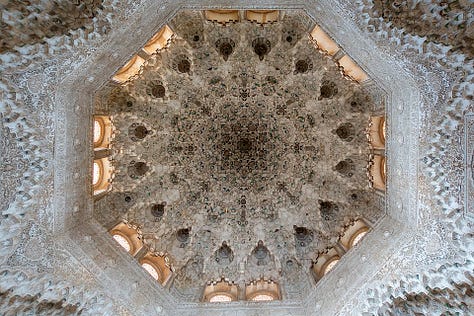

The Almoravids originated as a confederation of Sanhaja Berber tribes with a reformist Islamic zeal. By 1062 they had founded Marrakesh as their capital, and over the next decades they conquered all of Morocco and large parts of al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). This unprecedented unification allowed architectural ideas to flow freely across the Strait of Gibraltar, blending Andalusi and Maghribi traditions into a definitive “Hispano-Moorish” style. The Almoravids eagerly adopted the refined architectural concepts of al-Andalus,,for example, the complex interlacing arches that had evolved in the Great Mosque of Cordoba and the palace of al-Zahra, as well as polylobed (multifoil) arches and intricate carved decorations. At the same time, they brought in fresh influences from the eastern Islamic world, notably the introduction of muqarnas (stalactite or honeycomb carvings) as a decorative and structural element. Muqarnas domes and cornices, originally developed in Iran and Iraq, made their western debut under Almoravid patronage, such as in the prayer hall dome of the Qarawiyyin Mosque (added during its Almoravid expansion in 1120s) and the famous Almoravid Qubba in Marrakesh. The Almoravid Qubba Ba’adiyyin (c. 1117), a small ablutions pavilion that is one of the only Almoravid structures surviving intact, showcases these innovations: it features an elegant domed octagonal structure with horseshoe arches, jagged outline merlons, and muqarnas-carved interior vaulting, all elaborately decorated with carved floriated Kufic inscriptions and vegetal motifs. This fusion of Andalusi ornamental richness with new eastern techniques under the Almoravids set the stage for the “Moorish” aesthetic that would characterize Moroccan architecture henceforth.

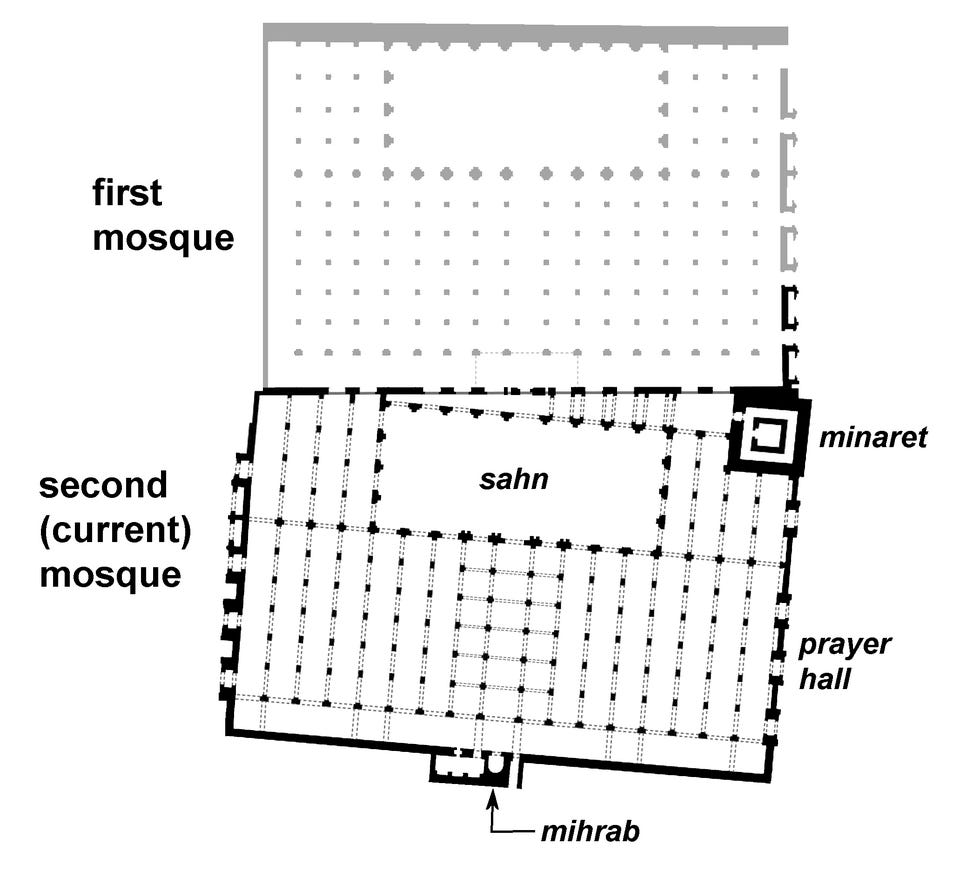

Functionally, the Almoravids standardized the hypostyle mosque form across their domain. Hypostyle (multi-columned) mosques with large rectangular prayer halls and courtyards had been typical of North Africa and al-Andalus since the earliest times, but the Almoravids undertook major mosque construction and expansion campaigns. In Marrakesh, they built the city’s first great mosque (the predecessor to the later Kutubiyya), and in Tlemcen (in present-day Algeria) they constructed another important mosque in 1082. They also famously enlarged the Qarawiyyin Mosque of Fez in 1129, giving it much of its present vast form. These mosques followed the classic hypostyle plan: a courtyard (sahn) leading to a covered hall of numerous rows of arches and columns oriented toward Mecca. Almoravid architectural planners often added a “T”-plan element, with a wider aisle leading to the mihrab (niche indicating the qibla) and a wider transverse aisle along the qibla wall, a layout seen in the Almoravid-expanded Qarawiyyin and later in the Almohads’ mosques. Almoravid mosques also began incorporating muqarnas-carved domes at significant points (like in front of the mihrab), a feature that became standard in later Moroccan mosques.

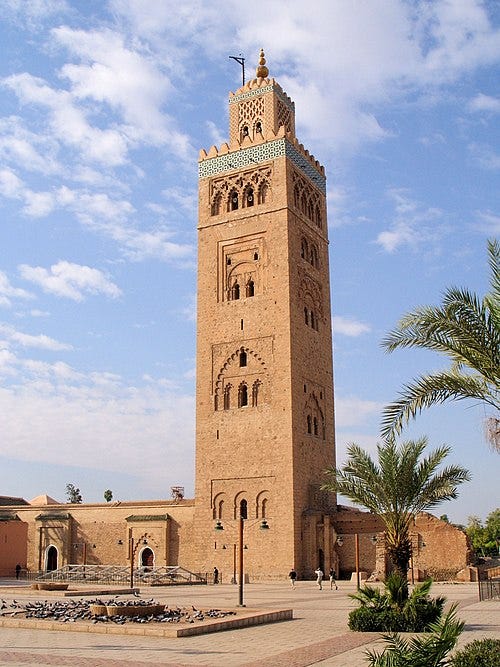

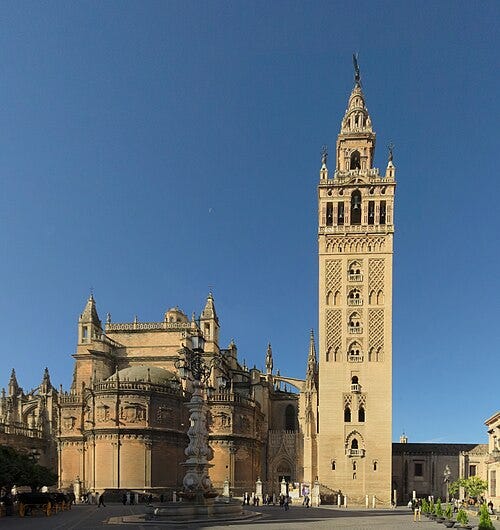

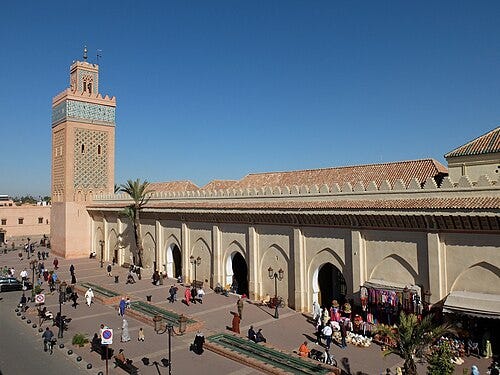

The Almohads, who supplanted the Almoravids in 1147, inherited this architectural legacy and amplified it on an even grander scale. The Almohad dynasty, also Berber (from the Masmuda tribes of the High Atlas), established Marrakesh as their capital as well and continued to use hypostyle mosque designs while emphasizing monumentality and austere grandeur in keeping with their reformist ideology. Under the Almohad caliphs, most notably Abd al-Mu’min (r. 1130–1163) and Ya’qub al-Mansur (r. 1184–1199), the empire reached its apogee, encompassing Morocco, western Algeria, and Muslim Spain. They embarked on building imperial mosques of unprecedented scale: the Kutubiyya Mosque in Marrakesh, the Giraldilla (Great Mosque) of Seville (in Iberia), and the Hassan Mosque in Rabat were all commissioned in the late 12th century. Each was planned to be the largest of its kind. For instance, the Kutubiyya Mosque (begun after 1147) features a vast hypostyle hall with 17 aisles and over 100 columns, allowing a capacity of some 20,000 worshippers. Its prayer hall is arranged in the familiar Almoravid/Almohad “T” pattern, with a broad central nave and transept emphasizing the mihrab axis. The Almohads’ architectural style in mosques favored slightly pointed horseshoe arches (an Almoravid innovation they continued), massive proportions, and relatively sparse ornament on walls, decoration was concentrated instead in carved minbars (pulpits) and mihrab areas, and in the form of the mosques’ most visible feature: their minarets.

Indeed, the Almohads are renowned for setting the prototype of the classic Moroccan minaret: a tall, square-section tower with minimal taper, often with two tiers of windows and crowned by a crenellated balcony and finial. The Kutubiyya minaret in Marrakesh (completed in the 1190s) stands ~77 m tall and became the model for countless others. It is noted for its harmonious proportions and subtle decoration, its facades have panels of blind horseshoe arches and interlacing polylobed arches in brick, as well as zellij (tile) ornament and a band of muqarnas near the top. The Almohads constructed two other monumental minarets on the same pattern: the Giralda of Seville (completed 1198, originally attached to the Great Mosque of Seville) and the Hassan Tower in Rabat (begun 1195). The Hassan Tower was intended to be the loftiest of the three, planned at 86 m high, as part of a grand mosque complex commissioned by Ya’qub al-Mansur. Although the mosque was left incomplete (al-Mansur died in 1199, with the minaret only reaching 44 m by then), the Hassan Tower remains a powerful symbol of Almohad ambition. Its red sandstone shaft, with ramps inside instead of stairs (an innovation inspired by the famed Lighthouse of Alexandria), and its severe but elegant exterior decoration (interlaced arches and geometric motifs on each face) strongly influenced later Moroccan minaret design. These Almohad minarets, visible for miles, announced the presence of the imperial faith and power; they also technologically demonstrated mastery of masonry and engineering, standing to this day as landmarks.

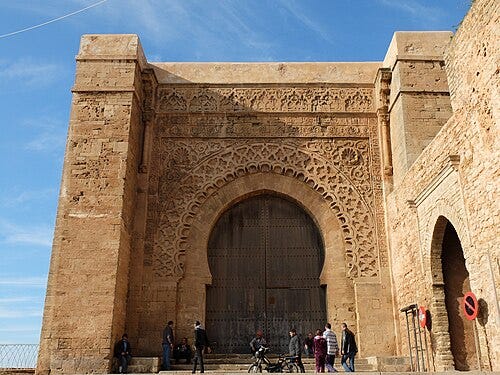

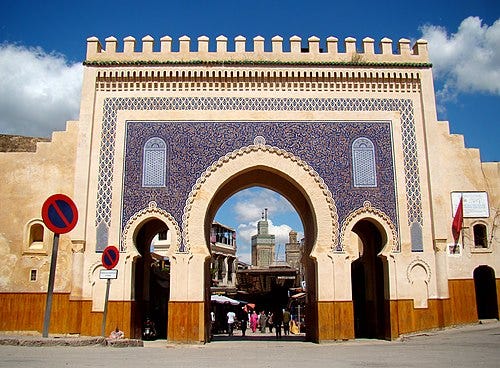

Another significant Almohad contribution was in fortification architecture. As rulers who faced frequent rebellions and invasions, the Almohads built and rebuilt city walls and gates on a grand scale. In Rabat, Ya’qub al-Mansur began constructing an enormous new imperial capital (Ribat al-Fath) with 5 km of walls, parts of which, including the majestic Kasbah of the Udayas gate, still exist. In Marrakesh, the Almohads strengthened the city’s enclosure and built a new royal citadel (kasbah) quarter (c. 1185) adjacent to the old city. The Bab Agnaou in Marrakesh is a famous Almohad-era gate that provided entry to this royal kasbah. Erected by Abd al-Mu’min around 1147 at the southwest of the city, Bab Agnaou showcases the Almohads’ combination of military solidity with ornamentation. It consists of a large horseshoe-arched opening flanked by solid towers. Uniquely, its limestone facade is richly carved: the arch is framed by multiple concentric bands of geometric pattern, the spandrels above the arch display intricate carved vegetal scrolls, and a bold rectangular Kufic inscription (Qur’anic verse) runs in a band above the arch, capped by a carved cornice with stylized merlons. The polychrome effect of the stone (alternating reddish and bluish-grey blocks) further accentuates the decoration. Bab Agnaou’s design, a horseshoe-arched gate enriched with geometric and epigraphic relief carving, was highly influential, echoing in later gates such as Fez’s Bab Boujeloud (20th-century), and stands as a testament to Almohad artistry within defensive architecture.

Under the Almoravids and Almohads, we also see the establishment of gardens and estates that integrated architecture with landscape. The Almoravids created the Agdal and Menara gardens in Marrakesh, and the Almohads continued the tradition of royal orchards and pleasure gardens (the Agdal Gardens in Marrakesh were expanded under them). These gardens often featured pavilions and water works, illustrating an early form of the indoor-outdoor architectural harmony that later Moroccan palaces would prize.

By the end of the 13th century, the Almohad Empire had fragmented, but their architectural legacy endured. Many structures from this era, mosques, minarets, walls, and gateways, survived to be inherited by subsequent dynasties. The Berber empire period unified the aesthetic of Morocco and al-Andalus, creating a coherent Andalusi-Maghribi style. Horseshoe and polylobed arches, muqarnas vaulting, zellij mosaic tilework (which the Almohads began to use in panel form), and the preference for certain forms (square minarets, fortress-like citadels with formidable gates) all became entrenched. The Almoravids and Almohads acted as both synthesizers and innovators: they fused prior influences and disseminated a mature Islamic architecture across Morocco, one characterized by the hypostyle mosque and its courtyard, the horseshoe arch motif, advanced decorative arts, and monumental engineering. Their imprint set the stage for the later flourish of Marinid and Saadian art, which would elaborate on these foundations.

In the 13th to 16th centuries, Morocco was ruled by two dynasties, the Marinids (1244–1465) and the Saadians (1549–1659), during which art and architecture reached new heights of refinement. These eras, especially under the Marinids in the 14th century and the Saadian sultan Ahmad al-Mansur in the late 16th century, saw a conscious florescence of culture often described as a golden age. Architects and craftsmen built on the structural forms established by the Almoravids/Almohads, but introduced greater decorative richness, new building types like madrasas, and innovative use of materials.

The Marinid dynasty, of Zenata Berber origin, made Fez their capital and presided over a particularly brilliant period of architectural patronage. While continuing to construct mosques and fortifications, the Marinids are most renowned for proliferating the madrasa (Arabic: madrasah, a college for Islamic theology and law) as a building type in Morocco. Prior to the 13th century, madrasas were uncommon in the Maghreb, but the Marinids, perhaps influenced by examples in Tunisia or by the desire to legitimize their rule through religious patronage, founded numerous madrasas in their cities. These institutions combined teaching facilities, student dormitories, and often a prayer hall, and they became showcases of ornamental craft.

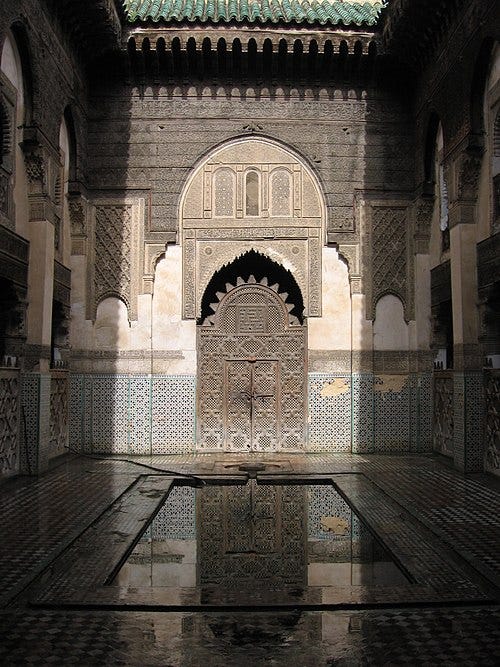

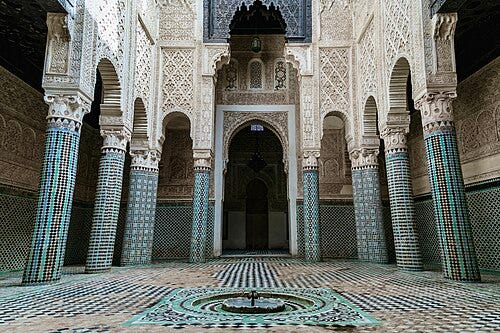

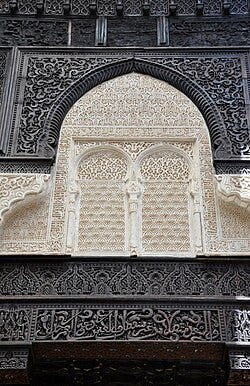

In Fez, the Marinids built at least a half-dozen major madrasas, many of which survive beautifully today. The Sahrij Madrasa (1321), Al-Attarine Madrasa (1325), and the crowning jewel, the Bou Inania Madrasa (1350–55), exemplify Marinid architecture’s splendor. The Bou Inania in particular is celebrated as “one of the largest Marinid buildings” and a masterpiece of design and decoration. Like other Marinid madrasas, it served both as an educational institute and a congregational mosque for its neighborhood, with a striking minaret signaling its presence. The Marinid madrasas typically follow a standard plan: a central courtyard (sahn) often with a small marble fountain, surrounded by a two-story arrangement of classrooms and dorm cells on the upper floor, and a prayer hall at the courtyard’s end. However, it was the decoration that Marinid patrons lavished upon these structures which sets them apart.

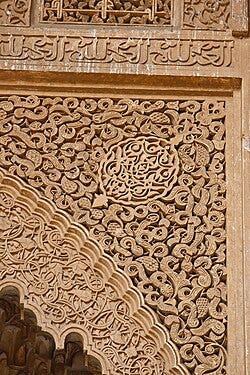

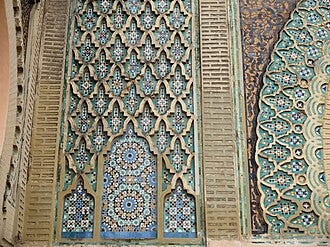

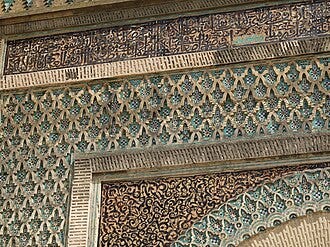

The Marinid decorative style can be seen as a sophisticated continuation of the Andalusian Nasrid style (from the contemporaneous Nasrid Kingdom of Granada) translated into religious edifices. In these madrasas, virtually every surface of the courtyard and prayer hall was ornamented. Lower walls were lined with polychrome zellij tile mosaics arranged in complex geometric patterns (often in star polygons and strapwork designs). Above the tiles ran bands of carved stucco plaster, densely covered with arabesques, muqarnas cornices, and Quranic inscriptions in elegant Maghribi script. Carved cedar wood was used for doors, screens, and the horizontal friezes, featuring lacy vegetal motifs and muqarnas carving in wood as well. The Bu Inania Madrasa’s courtyard is a showpiece of this work: its floors are marble and tile, its walls a tapestry of zellij and stucco, and its cedar cupola ceilings intricately painted and carved. The abundance and finesse of decoration are so great that one contemporary remarked the madrasa seemed “a bridal gown” of carved ornament. Crucially, Marinid decoration often incorporated Nasrid motifs from the Alhambra, for example, the use of muqarnas vaulting in the mihrab or porch, but adapted them to a purely Moroccan context (a small college rather than a grand palace). As one analysis notes, the Marinid madrasas demonstrate an “extreme delicacy and abundance of decorative treatment….characteristic of Marinid architecture,” taking what the Nasrids did in Granada and applying it to a pious, urban setting.

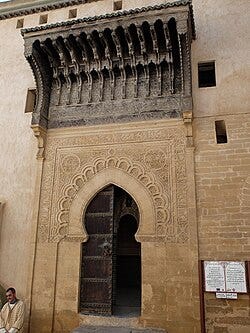

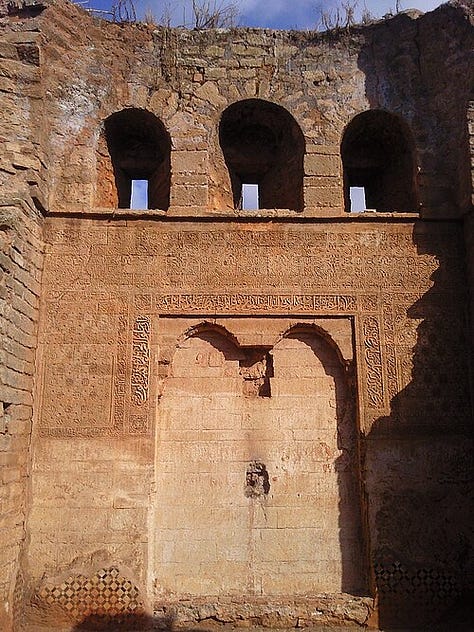

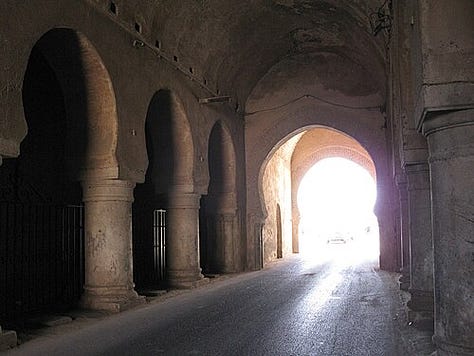

The Marinids also continued to build and embellish more utilitarian structures: Fez was at its zenith under their rule, and they endowed it with new city walls, forts, and a new royal city called Fes Jdid (New Fez) in 1276 to house the palace and garrison. In Fes Jdid, they built the grand Royal Palace and administrative facilities (most of which were later rebuilt by Alawites), as well as the Mellah (Jewish quarter) indicating the city’s plural makeup. The Marinid period is also known for the development of elaborate hydrraulic systems: they improved water supply with norias (waterwheels) and channels to feed fountains and baths in Fez. In terms of funerary architecture, the Marinids left evocative ruins of their necropolis on a hill overlooking Fez (the so-called Marinid Tombs), where large mausoleums once stood (now in ruin, but showing traces of zellij and carved plaster). In Rabat, the Marinids converted the old Roman/punic site of Chellah into a royal burial ground (Chellah Necropolis), adorning it with a zawiya (religious complex) whose elegant gate, minaret (with geometric tile decoration and stork nests today), and garden enclosure convey the melancholic charm of Marinid art in ruin. These show that Marinid architecture was not confined to madrasas; it permeated cityscapes with aesthetic and spiritual intent.

Overall, the Marinid era represented a flourishing of high culture. Fez in the 14th century became a renowned intellectual center of the Maghreb, thanks in part to the madrasas that “made the Maghrib, and especially Fez, a celebrated intellectual centre”. The Marinid sultans consciously sought to rival the splendors of Granada or Cairo, and while their resources were more limited, they succeeded in creating a legacy of uniquely Moroccan architecture that balanced elegance with restraint. As one historian put it, Marinid Fez “reached its height” during this period, with its principal monuments (madrasas, fondouks, palaces, mosques, fountains) dating from the Marinid zenith.

Following the Marinids and a brief interlude of Wattasid rule, the Saadian dynasty rose to power in the 16th century. The Saadians were an Arab-descended Sharifian dynasty, and under their most famous ruler, Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur (r. 1578–1603), Morocco experienced another cultural blooming. The Saadians, ruling from Marrakesh, are noted for their opulent architectural projects that in many ways revived and expanded the Marinid style, with some new influences due to the burgeoning global connections of the 16th century (including contact with Europe and the Ottoman Empire).

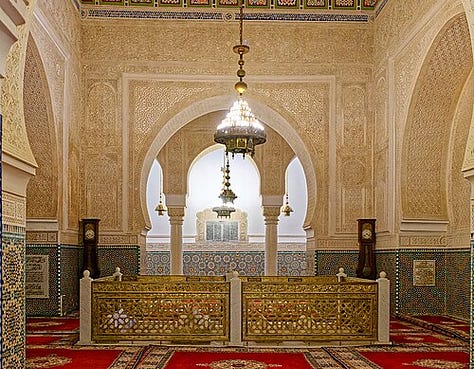

One of the Saadians’ greatest architectural legacies is the creation of the Saadian Tombs in Marrakesh. Although royal necropolises were not new (the Marinids had theirs at Chellah, as noted), the Saadian Tombs are exceptional in artistry. Located in the Kasbah district of Marrakesh (next to the Kasbah Mosque), this mausoleum complex was used by the Saadian family from the mid-16th century. Sultan al-Mansur greatly enlarged and embellished it after 1578, turning it into a lavish monument to his dynasty. The tomb complex centers on the so-called Hall of Twelve Columns, the mausoleum chamber of Ahmad al-Mansur himself. This chamber is renowned for its breathtaking combination of materials: twelve slim Carrara marble columns (imported from Italy) support an exquisitely carved cedar wood dome adorned with gilded muqarnas, a true fusion of Moroccan and international craftsmanship. No expense was spared; historical accounts and modern analysis confirm that Italian Carrara marble was imported in quantity, fine Indian teak and Sudanese gold were used for ornament, and the best local artisans were employed for the zellij and stucco work. Every surface of the Saadian tomb chambers is decorated: from the mosaic-tiled floors and lower walls, to the carved plaster with poetic inscriptions extolling the deceased, up to the cedar cupolas with intricately painted and gilded patterns. The effect is one of jeweled richness; a far cry from the austere simplicity favored by the earlier Almohads. The tomb complex was so sumptuous that when the succeeding Alawi dynasty took over, Sultan Moulay Isma’il felt it prudent to wall it off rather than destroy it (perhaps out of superstition or unwillingness to defile a sacred burial site). Thus, the Saadian Tombs survived intact, hidden behind walls until their “rediscovery” in 1917 by French authorities. Today they stand as a major attraction and a high point of Moroccan funerary art.

The Saadians also left their mark with secular architecture, most famously the El Badi Palace in Marrakesh. Built by Ahmad al-Mansur in the 1570s–1590s, reportedly funded by the hefty ransom paid by Portugal after the Battle of the Three Kings, El Badi was intended as a grand statement of Saadian power and sophistication. Contemporary descriptions marvel at its vast courtyard (with a massive central pool flanked by sunken gardens), its audience pavilion adorned with Italian marble columns (gifts from the Medici in Florence, it is said), and glittering tiles and gilded cedar ceilings. The palace’s name “al-Badi” means “The Incomparable,” and for a time it surely was, a triumph of Moroccan-Andalusian palace design influenced by the Alhambra and other Islamic palaces. Sadly, El Badi’s glory was short-lived: in the 17th century, Moulay Isma’il systematically dismantled it, carrying off its materials to his new capital Meknes. Today, the vast red-earth shell of El Badi, with its intact layout and some surviving fragments of decoration, gives an evocative sense of the scale of Saadian ambitions.

In addition to these iconic projects, the Saadians also contributed to religious architecture by restoring and enhancing mosques. For example, they renovated the 12th-century Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh and the Great Mosque of Taza, and they built new zawiyas (saint’s shrines) including one for the prominent Sufi sheikh Sidi ben Slimane al-Jazuli in Marrakesh. They also continued the madrasa-building tradition in a limited way: the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh, originally founded by the Marinids in the 14th century, was rebuilt in splendid form by the Saadians around 1565. The Ben Youssef Madrasa’s design and decoration closely parallel the Marinid models (courtyard with zellij, stucco, cedar, etc.), demonstrating how Saadian art was essentially a continuation and elaboration of Marinid-Moorish art. One could say the Saadians ushered in a renaissance of Moroccan architecture, refreshing traditional forms with even more opulence thanks to the global connections (European diplomats, Ottoman neighbors) that provided new materials and ideas.

Stylistically, Saadian architecture shows some new twists: for instance, more extensive use of morçarb (painted wood) ceilings with figurative-like geometric designs, possibly an influence from Ottoman or Persian arts. They also showed a taste for expansive gardens and public works, Ahmad al-Mansur built aqueducts and refurbished the Marrakesh water supply, and promoted urban beautification. Yet fundamentally, the Saadians revered the past; they saw themselves as inheritors of the Almoravid and Marinid legacy (even going so far as to patronize Fez and refurbish Qarawiyyin, etc., despite Marrakesh being their base).

The Marinid and Saadian periods were times of cultural flowering in Morocco, when architecture became a primary vehicle of royal patronage and prestige. The Marinids, ruling in a still-medieval context, focused on pious foundations like madrasas and managed to create an “architectural jewel” out of structured ornamentation. The Saadians, coming at the cusp of the early modern period, blended that inherited craftsmanship with new luxury, creating some of Morocco’s most famous showpieces like the Saadian Tombs. Both dynasties experimented with materials, the Marinids with abundant use of tile mosaic and carved stucco, the Saadians adding imported marble and gold, and both maintained the backbone of Moroccan design: the horseshoe arches, the serene courtyards, the arabesque and geometric motifs, and the balanced integration of architecture with its environment. Material innovations (such as the influx of Italian marble) and stylistic refinements (thinner carved patterns, more naturalistic floral motifs in Saadian plasterwork, etc.) enriched the palette of Moroccan artisans. By the end of the 16th century, Morocco possessed an architectural heritage as splendid and historically layered as any in the Islamic world.

In 1631, Morocco came under the rule of the Alawi (Alaouite) dynasty, a Sharifian line that continues to reign into the present day. The rise of the Alawis marked a new chapter in Moroccan architecture, one of both continuity and adaptation to changing times. Early Alawi rulers, especially the famed Moulay Isma’il (r. 1672–1727), sought to modernize and centralize the kingdom, and in doing so they left a distinct architectural imprint. At the same time, from the late 19th century and particularly after 1912, Morocco’s encounter with European colonial powers (France and Spain) introduced new architectural influences such as Art Deco and Neo-Moorish styles. The Alawi period thus spans from the 17th-century imperial constructions in Moroccan style to the 20th-century colonial and hybrid architectures that set the stage for modern Morocco.

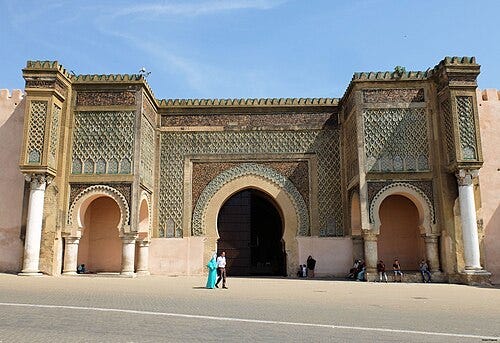

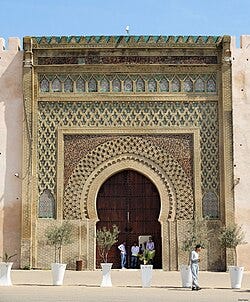

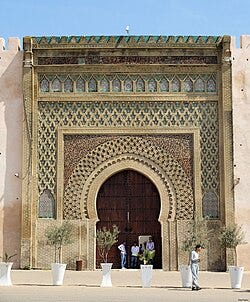

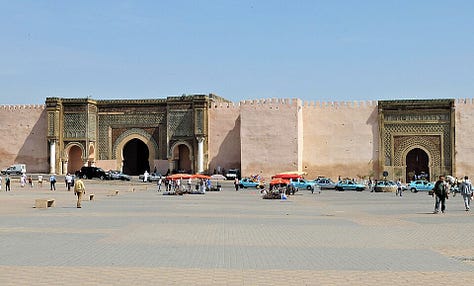

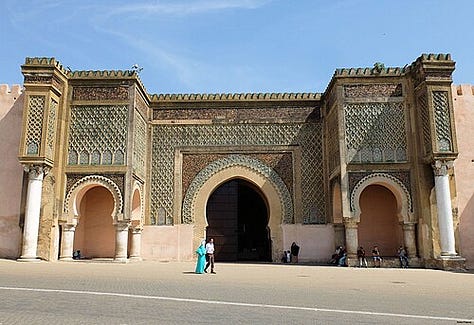

One of the early Alawi dynasty’s monumental projects was the creation of a new imperial capital by Moulay Isma’il. In 1672, he chose the city of Meknès to build his Versailles-inspired court, transforming it from a provincial town into a vast imperial city. Meknès under Moulay Isma’il was surrounded by over 25 km of formidable ramparts, some up to 15 m high, punctuated by monumental gates like the famous Bab Mansur al-‘Alj. This gate, completed around 1732, features a grand horseshoe arch flanked by massive semi-circular towers and is decorated with zellij tilework in a stunning zigzag and interlaced pattern, as well as panels of Arabic inscriptions praising the sultan. With its scale and confident embellishment, Bab Mansur is often cited as one of the masterpieces of Maghribi gateway architecture, synthesizing earlier Almohad gate design with a more exuberant coloristic effect via tiles.

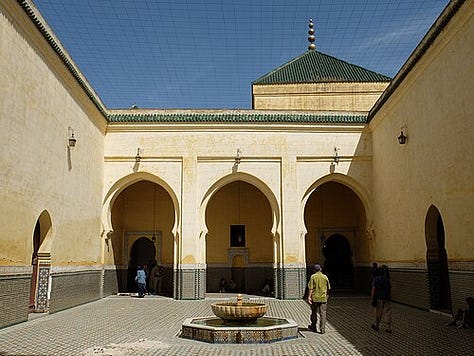

Inside Meknès, Moulay Isma’il’s royal Kasbah (citadel) was a vast complex containing palaces, audience halls, harems, gardens (some designed in the traditional Andalusian garden style with fountains and fruit trees), armories, and immense storage facilities. The so-called Heri es-Souani granaries and stables, for example, are engineering marvels, a series of high-vaulted chambers designed to store grain and house thousands of royal horses, cooled by thick earth walls and an ingenious water cistern system. In keeping with tradition, many buildings were of rammed earth (pisé) and brick, with whitewashed or lime-plastered exteriors, creating a austere facade to the outside. But courtyards and interior rooms could be lavishly decorated: Moulay Isma’il imported Italian marble columns (famously, some pillars in Meknès came from the ruins of Volubilis nearby and others from quarries via the port of Rabat) and had artisans create carved and painted wood ceilings and zellij floors for his palaces. The design of Meknès was clearly Hispano-Moorish (Spanish-Moorish) in style, meaning it followed the layout logic of a sprawling Islamic royal city but also absorbed some contemporary European influence in planning and decoration. For instance, the concept of very long straight avenues within the Kasbah and the enormous scale of certain structures indicate awareness of Baroque architecture (Moulay Isma’il notably maintained correspondences with France’s Louis XIV, even seeking European engineers). The Royal Palace of Meknès included a grand courtyard reportedly inspired by European models, yet ornamented with Moroccan tile and carving, a “harmonious fusion of Islamic and European styles in the Maghreb of the 17th century”. UNESCO describes Meknès as “an impressive city of Hispano-Moorish style, surrounded by high walls pierced by monumental gates,” which shows “the harmonious blending of Islamic and European architectural and town-planning elements” in that era. Meknès is thus considered the first great work of the Alawite dynasty, reflecting the grandeur of its creator Moulay Isma’il and the continuity of the Moroccan imperial architectural tradition into early modern times.

Elsewhere in Morocco, the Alawi sultans also left their mark. Moulay Isma’il repaired or strengthened many old cities’ defenses, renovated mosques (he is credited with refurbishing the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez and adding to the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II there), and built kasbahs (forts) at strategic locations. The Kasbah of Moulay Isma’il in Meknès, as mentioned, is the chief example, essentially an entire walled city. In northern Morocco, he constructed a series of forts to secure against Ottoman influence coming from Algeria. Subsequent Alawi rulers, like Sidi Mohammed ben Abdallah (Mohammed III, r. 1757–1790) and Moulay Hassan I (r. 1873–1894), continued a policy of architectural patronage but often on a smaller scale, restoring rather than radically building anew (partly due to more limited resources and constant military challenges).

One exceptional Alawi project in the 18th century was the foundation of Essaouira on the Atlantic coast. Sultan Mohammed III, wishing to create a modern port city to increase trade (especially with Europe), commissioned in 1765 a French engineer, Théodore Cornut, to design the fortifications and plan of Essaouira (then called Mogador). The result was a unique example of an 18th-century fortified town built according to European military architecture principles in a North African context. Essaouira’s layout has straight orthogonal streets (a grid much unlike traditional medinas) and a system of bastions and ramparts along the sea, resembling French or Vauban-style forts. Yet the city still incorporated Moroccan elements: an internal kasbah (for the governor’s residence), mosques and synagogues, and the typical white-and-blue painted houses of Atlantic Moroccan towns. Essaouira thus embodied the Alawi willingness to integrate European expertise while maintaining a distinctly Moroccan character, the city’s very name in Berber means “the little fortress,” and it successfully linked Morocco’s interior with the world as a major seaport. UNESCO recognizes Essaouira as “an outstanding example of a late-18th-century European fortified seaport town translated to a North African context”. Its impressive sea walls (the Skala), complete with European cannons, and the grid-pattern streets lined with arcaded shops differentiate it from older cities and foreshadow the coming colonial urbanism, yet it was an Alawi royal endeavor.

By the late 19th century, Morocco’s relative isolation was diminishing as European powers increased their economic and political penetration. This culminated in the establishment of the French Protectorate (1912–1956) over most of Morocco (and a smaller Spanish Protectorate in the north and southern Western Sahara region). The colonial period brought a new wave of architectural and urban development that both contrasted with and drew from Morocco’s traditional forms. Under General Hubert Lyautey, the first French Resident-General, a policy of building “villes nouvelles” (new towns) adjacent to the old medinas was implemented. French urban planners like Henri Prost designed modern cities with wide boulevards, parks, and administrative quarters, intentionally preserving the historic medinas alongside. This dual-city structure left a lasting mark on Morocco’s urban centers.

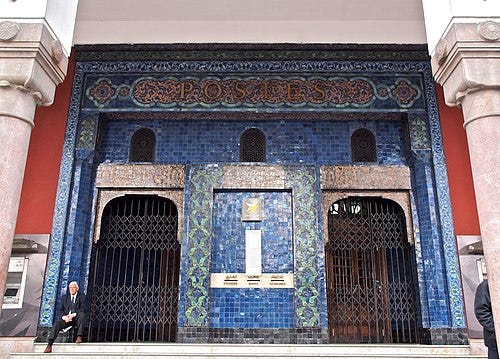

In terms of style, the early 20th century saw the creation of what is often termed the “Mauresque” (Neo-Moorish) style, a colonial architectural style that fused European modern construction with decorative motifs inspired by Moroccan tradition. Lyautey encouraged architects to respect Moroccan architectural idioms, which led to public buildings that incorporated horseshoe arches, zellij decoration, mashrabiya-style screens, and so on, within fundamentally European Beaux-Arts or Art Deco forms. The city of Casablanca became a showcase of this experiment. During the interwar period, Art Deco flourished in Casablanca’s rapidly expanding city center, but often with a Moroccan twist: buildings featured zellij friezes, twisted columns or merlons resembling those of Marrakech, and other local design elements grafted onto streamlined modern silhouettes. For example, the Grande Poste (Main Post Office, 1918) in Casablanca has an Art Deco symmetry but is adorned with mosaic tilework and has keyhole arches on its facade, blending the two aesthetics. The Palais de Justice (Courthouse, 1925) in the same city similarly mixes a modern civic monument layout with Moroccan-inspired courtyards and decor. This trend of Neo-Moorish architecture under the French is sometimes also called Moroccan Art Deco or Arabesque Deco. As one travel writer quipped, Casablanca became a “living museum of Art Deco architecture, blending Moroccan craftsmanship with European modernism”. Indeed, entire neighborhoods in Casablanca, often nicknamed “Petit Paris”, feature apartment buildings from the 1930s with geometric wrought iron balconies alongside Islamic geometric tiles and stucco work. National Geographic Traveller notes that “neo-Moorish buildings merging Islamic and Art Deco elements” are highlights of Casablanca, such as the Wilaya (Governorship) building with its clocktower, the Post Office, and even the 1930 Cathedral of Sacré-Coeur which, while European-gothic in function, sported horseshoe arches and detailing that echo Moroccan forms.

In the capital Rabat, the French also constructed official buildings in a neo-Moorish idiom, for example, the Rabat railway station and the Bank of Algeria building had classic Islamic arches and green-tiled roofs but were essentially modern facilities. Entire new towns like Ville Nouvelle of Rabat and Nouaceur district in Casablanca were laid out with geometric precision. Yet the Protectorate regime also undertook restoration of historic monuments (a mixed legacy, but sites like the Bab Boujeloud gate in Fez were actually built anew in 1913 in “Moorish” style to beautify the old city entrance). Meanwhile, in northern Morocco under Spanish control, Tetouan saw Spanish architects produce an Andalusian-inflected Neo-Islamic style (e.g., the Hassan II Square arcade in Tetouan with elegant horseshoe arches and decorative tilework shows this blend).

By the mid-20th century, Morocco thus had a layered architectural environment: intact medieval cities, new colonial quarters with eclectic styles, and early modernist buildings. The influence of the Protectorate period on architecture was significant in terms of introducing new materials (reinforced concrete, for instance) and styles (Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Streamline Moderne), but it often came with an orientalist appreciation of Moroccan motifs. Even after independence in 1956, this cross-pollination persisted. Some postcolonial public architecture, like the Mausoleum of Mohammed V in Rabat (completed 1971), continued the Neo-Moorish style with sumptuous traditional craftsmanship (its exterior of white marble and green tiled pyramidal roof, and interior of carved cedar and stucco, were done by traditional artisans). The spectacular Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, completed in 1993, likewise is a modern structure that proudly revives historical Moroccan forms on an immense scale (featuring a 210 m minaret, the world’s tallest, ornamented with traditional motifs).

The Alawi era from the 17th through mid-20th centuries represents both a continuity of indigenous architecture, through projects like Meknès and the sustained use of Moroccan decorative arts, and a period of transition under foreign influence, leading to new hybrid styles. The Alawite sultans like Moulay Isma’il entrenched the classical Moroccan aesthetic in imperial projects (Meknès being the prime example of a city “harmoniously combining Islamic and European conceptual elements” of its time). Later, the Protectorate introduced European architectural modernity, yet often filtered through a “Moorish Revival” lens. By 1950, one could find in Morocco Art Deco boulevards and Neo-Moorish civic buildings in the new cities, and still step into a perfectly preserved medieval medina next door. This juxtaposition has become a defining feature of Moroccan cityscapes. The colonial encounters added Art Deco and Modernist layers onto Morocco’s architectural palimpsest while also sparking renewed appreciation for the craftsmanship of Moroccan artisans, which the French touted in their Mauresque works. The result was an architectural heritage enriched rather than erased by colonialism, setting the stage for post-independence developments that Part Two will explore, including how modern Moroccan architects negotiate the balance of tradition and innovation.

Across the long span of Moroccan history covered in this part, several major architectural typologies emerged and endured as defining features of the built environment. Understanding these forms is key to understanding the functional and cultural significance of Morocco’s architecture. Among them are the hypostyle mosque, the horseshoe arch, the kasbah, the ribat, and the riad. Each of these is not a single building but a type, a template that appeared repeatedly (with variations) over time, serving specific needs and symbolisms in Moroccan society.

The hypostyle mosque is the classic early Islamic mosque type, characterized by a prayer hall supported by numerous columns forming a grid, often with a large open courtyard (sahn) adjacent. In Morocco, this remained the dominant mosque form from the 8th century through the 20th century. The great mosques of Fez, Marrakesh, Rabat, and other cities are hypostyles. For example, the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez (founded 859 and expanded in the 10th and 12th centuries) has a vast hypostyle hall of rows upon rows of horseshoe arches, and the Kutubiyya Mosque in Marrakesh (1158) similarly has 17 aisles of columns. Culturally, hypostyle mosques facilitated communal worship by allowing scalable expansion, one can extend the hall by adding more bays as needed (as happened at Qarawiyyin and other mosques over time). The forest of columns creates a sacred rhythm and modular space that can accommodate many worshippers. The courtyard serves for ablutions and overflow prayer space, reflecting a climatic adaptation (an open-air component for light and ventilation). In Moroccan society, the mosque was not only a place of prayer but often an anchor of the neighborhood. The hypostyle design, with its straightforward repetitive structure, meant mosques could be constructed relatively quickly and with local materials (brick, stone, or palm trunks in earlier centuries). Over time, these mosques accrued great spiritual significance, e.g. Qarawiyyin became a university, and mosques like the Grand Mosque of Meknès helped legitimize rulers who built or refurbished them. Architecturally, the hypostyle form also allowed insertion of decorative domes (like those with muqarnas) at focal points such as in front of the mihrab, showcasing artistry without altering the overall layout. In summary, the hypostyle mosque type symbolized the unity of the worshippers (all rows equally facing Mecca) and the continuity of the faith; a visual metaphor of an “Islamic community” under the roof of the house of God. Its persistence in Morocco attests to conservatism in sacred architecture and the importance of communal religious practice.

If one motif could be called the “signature” of Moroccan and Moorish architecture, it is the horseshoe arch (semi-circular or slightly pinched arch that continues beyond the semicircle). Horseshoe arches were used by the Visigoths in Iberia and then adopted and adapted by early Islamic builders in al-Andalus in the 8th century. This form entered Morocco both through Idrisid connections to al-Andalus and via the Aghlabids of Ifriqiya; by the 9th–10th centuries, it had become predominant in the Maghreb. A horseshoe arch, more curved than a half-circle, creates an aesthetically pleasing, bulbous shape that became ubiquitous, from mosque arcades and palace courtyards to city gates. In Moroccan culture, the horseshoe arch came to signify Islamic identity and patrimony; it visually sets Islamic architecture apart from classical Roman arches or Gothic pointed arches. Functionally, horseshoe arches can be structural but often are used decoratively or symbolically (for instance, blind horseshoe arches on a facade for ornament). Many horseshoe arches in Morocco are “broken” or pointed horseshoes (a variation that emerged under the Almoravids and Almohads) which have a slightly ogival shape. The persistence of the horseshoe arch, one can see it in the 9th-century ruins of Sijilmasa as well as the 20th-century Casablanca courthouse, speaks to a cultural continuity. It evokes the great age of Córdoba and Marrakech, and thus architects continue to use it as a nod to heritage. The arch’s form also has practical advantages: it can carry load well and when poly-lobed or interlaced, it allows creation of perforated screens and sophisticated transitions in structural bays. Beyond its utility, Moroccans imbued the horseshoe arch with an artistic language: often outlined with voussoirs of alternating colors or with carved voussoirs, it frames space like a gateway into the serene interiors of mosques and palaces. As a result, the horseshoe arch is both an engineering element and a cultural symbol, synonymous with Moroccan-Islamic art itself.

The term kasbah (Arabic: qasaba) refers to a fortress, typically the fortified quarter of a city or a stand-alone fortress in a strategic location. In Morocco, kasbahs have been integral since antiquity in providing defense and asserting authority. Every major historic city had a kasbah; a citadel often on elevated ground, housing the governor’s residence and barracks. Examples include the Kasbah of Marrakesh (the royal district created by the Almohads in the 12th century), the Kasbah of the Udayas in Rabat (an earlier Almoravid/Almohad fort overlooking the river and ocean), and the numerous kasbahs built by Moulay Isma’il across the land. In more rural or tribal contexts, “kasbah” can also mean a fortified mansion or small keep of a local chieftain (often seen in southern oases, like Kasbah Amridil in Skoura, which is a mudbrick mini-fortress home). The cultural significance of kasbahs is tied to power and protection. They were the centers of administrative control, in a city, whoever held the kasbah held the city. Their walls offered refuge in times of strife. Architecturally, kasbahs in Morocco are typically characterized by thick defensive walls, crenellations, angle towers, and a lack of exterior ornament (aside from perhaps a monumental gate). They are often constructed in rammed earth or mud brick, especially in the south, giving them a reddish, organic appearance blending with the landscape. The Kasbah of Ait Benhaddou (a famous fortified village or ksar) demonstrates the iconic silhouette of kasbah towers and merlon crenellations rising from a hillside. In Morocco’s memory, kasbahs symbolize the feudal and tribal strongholds, hence the phrase “the Casbah” often romanticized in literature as the labyrinthine old fortress quarter. Many kasbahs also contained palaces and were centers of art (for instance, the Alawi kasbahs in Meknès had elaborate palatial quarters). As Morocco entered the modern era, some kasbahs lost military function and became neighborhoods (e.g., Tangier’s Kasbah is now largely residential and touristic), yet the word still evokes secure, old-world authority. Even during the Protectorate, the French often repurposed kasbahs for their garrisons or offices (recognizing their strategic value). In short, kasbahs are the physical embodiment of defensive architecture and governance in Moroccan history, from which the surrounding town often grew.

A ribat is a type of fortified convent or frontier fortress, initially established during the early spread of Islam for pious soldiers (Murabitun) guarding the frontier and often serving as centers of spiritual retreat or missionary activity. The very name Rabat, Morocco’s capital, derives from an original Ribat al-Fath (“Camp of Victory”) founded by the Almohads in the 12th century at the site. While ribats were more common in Tunisia (e.g., the famous ribats of Sousse and Monastir), Morocco had its share. Early accounts speak of ribats along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts where warrior-monks kept watch for Christian naval incursions and also spread Islam among local Berbers. One notable example is Ribat Shalla in Salé, and Ribat al-Malik near Asilah. Many such structures have vanished or were absorbed into later fortifications (for instance, the Kasbah des Udayas in Rabat began as a ribat). The concept of the ribat in Morocco also evolved into the zawiya or marabout lodge, places where Sufi fraternities would establish a base, often fortified lightly, serving both spiritual and sometimes defensive roles. Culturally, ribats and later zawiyas played a role in educating and integrating society, they were early centers of learning, as well as sanctuaries. The ribat’s architectural plan was generally a small fort with a square or rectangular layout, thick walls, maybe a tower, and internal rooms for living and worship. Over time, the need for ribats as military frontier posts declined as the frontiers moved or stabilized (after the Reconquista, the coast was no longer a frontier in the same way). But the legacy lives in language and urban morphology, any fortified monastery-like complex might be called a ribat, and many Moroccan cities (Rabat, Rbita in place names) recall these origins. In essence, the ribat typology signifies the unity of military and spiritual endeavor in early Islam, a place where one could serve God and defend the community simultaneously. In Moroccan memory, it underscores how the faith was spread and defended in its formative years.

The term riad (Arabic riyad, meaning “garden”) in Morocco refers to a traditional house or palace organized around an inner courtyard garden. The riad is a hallmark of Moroccan domestic architecture in medinas and also of palace design. A riad’s typical features include a central open-sky courtyard, often rectangular or square, with a sahrij (shallow fountain or pool) in the middle for reflection and cooling; around this courtyard, four sides of living quarters with galleries or arcades open inward. High walls on the exterior of the house present a plain facade to the street, while the interior is focused on the courtyard, which is often lush with greenery, citrus trees, palms, jasmine, and decorated with zellij floors and carved stucco. The riad form maximizes privacy, in line with Islamic cultural norms: the house turns inward, so all windows and balconies face the secure central space rather than the public street. This served to protect the family’s private life from outside view and also created a quiet oasis within the noisy, narrow streets of the medina. Culturally, the riad reflects the concept of home as an introverted paradise, a mini-Eden in the middle of the city. The garden and fountain symbolically evoke the Quranic vision of paradise (“gardens with running water”), a theme cherished in Islamic art. Functionally, riads were also well-adapted to climate: the courtyard provided light and air circulation, while the thick exterior walls shielded from heat and noise. Many grand historical mansions (e.g., the 19th-century Bahia Palace in Marrakesh) are essentially large riads with multiple courtyards. Even modest traditional houses followed the riad concept on a smaller scale, a central patio used for family gatherings, often open to the sky or with a removable cover. The persistence of the riad layout over centuries shows its resonance with social structure: it facilitated the extended family living together, with rooms around the courtyard for different family branches, all centered on a common space. In recent decades, many old riads have been restored and converted into guesthouses, which speaks to their enduring appeal; visitors marvel at stepping from a chaotic street through a small door into a tranquil courtyard with zellij, carved wood, and greenery. The term “riad” itself has thus become synonymous with Moroccan hospitality and design. In summary, the riad typology encapsulates how Moroccan architecture creates serene, intimate spaces hidden within robust, unassuming exteriors, a physical metaphor for the value placed on family, hospitality, and the subtle enjoyment of beauty in private life.

These five typologies (mosques, arches, kasbahs, ribats, and riads) each had specific roles: spiritual, structural, defensive, ascetic-military, and residential. Together, they form a core vocabulary of Moroccan architecture. Their recurrence across historical periods demonstrates continuity (for instance, the horseshoe arch appearing in Idrisid Fez and 20th-century Rabat, or kasbahs from medieval to Alawi times). Yet each type also evolved: e.g. mosques gained embellishments and grew larger; kasbahs shifted from pure forts to sometimes palatial enclaves; riads in the modern era sometimes feature new materials like iron and glass but retain the concept. Importantly, these forms often intersect in single complexes, a royal kasbah might contain a mosque with horseshoe arches, and a palace within might be a series of riads; a ribat might evolve into a kasbah or zawiya with an internal garden. This interconnectedness underscores that Moroccan architecture is integrative: defensive needs, climatic responses, social norms, and aesthetics all weave together. The typologies listed were not static schemas but living traditions that catered to the needs of Moroccan society: faith, security, community, and family. Their cultural significance is evident in the way they are cherished and preserved. As Morocco modernized, new typologies (like theaters, train stations, high-rises) emerged, but even those often borrow elements from these traditional types (a modern hotel might be designed around a riad-like atrium, a parliament building given a kasbah-style outline, etc.). In essence, the endurance of these forms speaks to a deep continuity in Moroccan culture, where the past dialogues constantly with the present through architecture.

From prehistoric habitation through antiquity and the Islamic Middle Ages to the dawn of modernity, Morocco’s architecture evolved on strong historical foundations. In this first part of our study, we traced how the interplay of indigenous Berber traditions and successive external influences, Phoenician and Roman classical styles, Arab-Islamic and Andalusian aesthetics, and finally European interventions, produced a distinctive architectural identity by the early 20th century. Key structural and artistic concepts were established in the first millennium of Morocco’s built history. The Romans left the idea of the planned city with its arches, basilicas, and infrastructure, as seen at Volubilis. The advent of Islam added new functions and forms: the mosque and minaret, the medina with its labyrinthine urbanism, and the qasba (citadel) as an emblem of authority. Under Berber dynasties like the Almoravids and Almohads, Moroccan architecture was unified and endowed with the emblematic horseshoe arch, ornate dome, and geometric art, a legacy continued by later dynasties. The Marinids and Saadians ushered in eras of cultural fluorescence, refining decorative arts (zellij tilework, carved stucco, wood marquetry) to a pinnacle and creating institutions like madrasas that enriched the architectural landscape. The Alawis maintained continuity, erecting monumental complexes such as Meknès that blended traditional Hispano-Moorish style with Baroque-scale planning. And even as European powers arrived, they too paid homage to the established motifs, incorporating Moorish arches and Moroccan craftsmanship into colonial-era designs.

In short, by the mid-20th century Morocco had achieved a remarkable layering of architectural heritage. The structural foundations, thick pisé walls, hypostyle halls, courtyard-centric layouts, and aesthetic foundations, horseshoe arches, riad gardens, mastery of geometric and arabesque decoration, were all in place, having been perfected over centuries. These became the wellspring from which contemporary Moroccan architecture could draw inspiration. The enduring presence of these forms attests that the first millennia of dynastic evolution in Morocco established not only the physical monuments of cities like Fez, Marrakesh, and Meknès, but also a design ethos recognizable in everything from humble homes to grand imperial works.

By laying these foundations, Morocco’s early builders ensured that future generations could innovate without severing ties to the past. Part Two will explore how, upon this foundation of form and technique, Moroccan architects and artisans developed a dazzling repertoire of ornament (tile mosaic, carved plaster, woodwork), how they approached urbanism (from the medina model to modern city planning), and how the country’s architecture adapted in the modern era and post-independence, from neo-traditional revivalism to cutting-edge contemporary designs. The story of Moroccan architecture is thus one of continuity and creativity: a long tradition capable of renewal in each era.

References:

Archaeological Site of Volubilis. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. whc.unesco.org/en/list/836/. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Medina of Fez. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. whc.unesco.org/en/list/170/. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Historic City of Meknes. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. whc.unesco.org/en/list/793/. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Medina of Essaouira (formerly Mogador). UNESCO World Heritage Centre, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. whc.unesco.org/en/list/753/. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. Lixus. Britannica, britannica.com/place/Lixus. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Wong, Kate. Ancient Fossils from Morocco Mess Up Modern Human Origins. Scientific American, 8 June 2017. www.scientificamerican.com/article/ancient-fossils-from-morocco-mess-up-modern-human-origins/. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Wikipedia. Hassan Tower. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hassan_Tower. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Archnet. Bab Agnaw (Bab Agnaou), Marrakech, Morocco. Archnet (MIT & Aga Khan Trust for Culture), archnet.org/sites/2847. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Archnet. Madrasa al-Bu’inaniya, Fez, Morocco. Archnet (MIT & Aga Khan Trust for Culture), archnet.org/sites/1725. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Roller, Sarah. The Saadian Tombs. History Hit, 24 Nov. 2020. historyhit.com/locations/the-saadian-tombs/. Accessed 4 March 2025.

National Geographic Traveller (UK). Dhuga, Amelia. Why Casablanca is the Best Moroccan City for Architecture Fans. NatGeo Traveller, 7 June 2025. nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/best-moroccan-city-for-architecture-casablanca. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Discover Islamic Art - Museum With No Frontiers. The Muslim West: Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (Artistic Introduction). museumwnf.org, 2010. islamicart.museumwnf.org/gai/isl/page.php?theme=4. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Metropolis Magazine. Fleisher, Elan. The Art of the Moroccan Riad. Metropolis, 23 Dec. 2013. metropolismag.com/projects/the-art-of-the-moroccan-riad/. Accessed 4 March 2025.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archaeological Site of Volubilis - Outstanding Universal Value. (Content License: CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0). whc.unesco.org/en/list/836/. Accessed 4 March 2025.

Wikipedia. Architecture of Fez. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Architecture_of_Fez. Accessed 4 March 2025.

My dearest Rogue— how I admire thy endurance.

My first cup of coffee was left over from yesterday’s pot as I began this journey. I was engaged as I put up my next pot, which is a perk, adding water, assembling the pot, etc, as I continued. I set the timer. I like 8 minutes. I listened to it peeking, comforted my cup would soon be refilled. The alarm went off. I let it sit for a few as o set a marker where I left off. I go to pour the cup—clear water! Hot, yes, but NOT coffee. I had forgotten to put the grounds! Mesmerized by your work I managed to perk a pot of hot water.

So I add the coffee this time. The water is already hot so it starts to perk immediately. I set another timer. I return to this post. On, on, on… no buzzer yet. FINALLY! the fresh coffee has finished! I let that sit as I finish another section to cool so I may sip… sip… sip…

Still. More time. Another cup. Now I am hungry. I gather something to eat—still engaged…

And finally!!! Over 45 minutes later and 4 cups in—Fini!

This should be a recorded library—There is a listen mode on Substack. I believe it is a good way to study and learn from these epic posts. To listen then read, scanning detailed parts. I highly recommend trying this method for future subscribers. In fact, I think I will go back to other of your posts and just listen again. We learn in multiple ways. Substack offers all of them. How wonderful!

Absolutely spectacular! You captured the evolution of Moroccan architectural history so beautifully that I may have to delve a little deeper. I’m especially intrigued by the urban elements you describe (and those decorations!). Thanks for posting.