Holy Saturday, situated between Good Friday and Easter Sunday, occupies a unique space in the Christian liturgical calendar. Often overshadowed in both popular observance and artistic representation, it nevertheless holds deep theological and spiritual meaning.

Holy Saturday is the final day of Holy Week and the third day of the Paschal Triduum, a period commemorating the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ. It is a day marked by silence, as Christ's body lies entombed. The Church refrains from Mass until the evening Easter Vigil, during which the new Paschal fire is blessed and the resurrection is anticipated. According to Paul F. Bradshaw, this liturgical stillness is rooted in early Christian practice, where the day was observed in fasting and quiet anticipation (Bradshaw 76–79). The solemnity underscores the paradox of death and expectation, serving as a bridge between despair and hope.

Central to Holy Saturday is the doctrine of the "descent into Hell," or the Harrowing of Hell, which is embedded in the Apostles' Creed: “He descended to the dead.” Early Christian writings and apocryphal texts such as the Gospel of Nicodemus elaborate on this moment, imagining Christ liberating the righteous from Hades. Caroline Walker Bynum interprets this descent as theologically critical for understanding Christ’s solidarity with human suffering and the totality of death’s defeat (Bynum 41–46). In patristic theology, particularly in the works of Irenaeus and Augustine, this descent was framed as a triumphant victory over death, further reinforcing Christ’s divine authority.

Holy Saturday is a profoundly liminal day. Alan E. Lewis, in Between Cross and Resurrection, explores the theological weight of this interstitial time. He argues that Holy Saturday represents the “suspension of salvation history,” where God's silence mirrors the existential despair of the disciples (Lewis 170–172). The term “liminality,” borrowed from anthropology, aptly characterizes the psychological and spiritual threshold between the devastation of Good Friday and the joy of Easter Sunday. This in-between state invites believers to meditate on absence, silence, and waiting; not as passive experiences but as the necessary crucible for transformative hope.

Holy Saturday’s lack of direct biblical narration posed a challenge for artists. Unlike the vivid imagery of the crucifixion or the resurrection, the tomb scene remains inherently static. However, artists across centuries have turned to apocryphal texts, homilies, and liturgical practices to animate this moment. These artworks often merge historical imagination with theological insight, producing deeply evocative representations of Christ’s entombment or descent.

One such masterwork is Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521), housed in the Kunstmuseum, Basel. Holbein’s striking depiction of Christ’s lifeless body, displayed in a stark, unadorned tomb, serves as an exemplary representation of Holy Saturday’s profound silence and the raw reality of death. The unidealized presentation of Christ’s body, viewed in extreme realism, invites the viewer into an intimate confrontation with death, offering a meditation on mortality while reinforcing the paradox of impending resurrection.

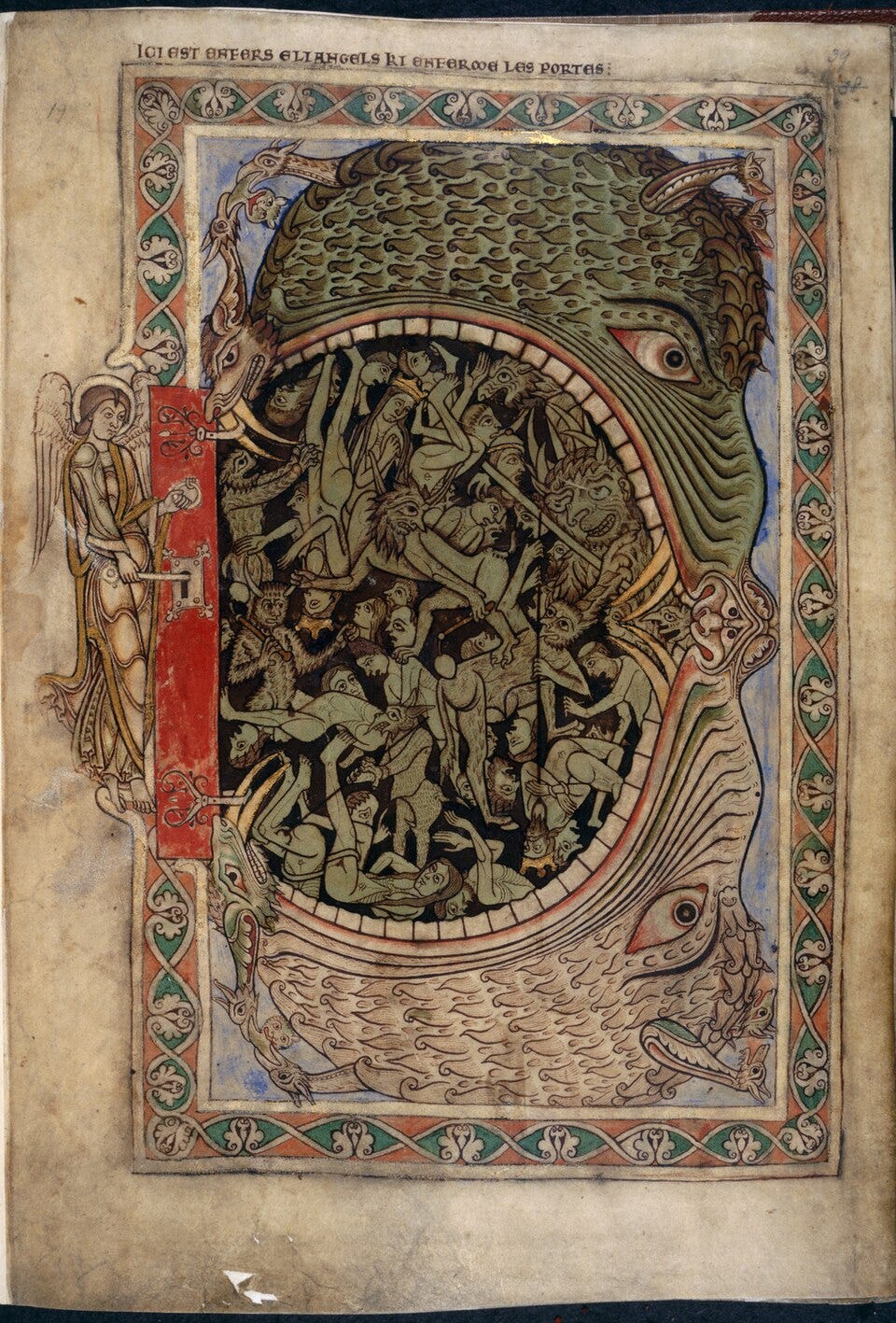

The Harrowing of Hell emerged as the most visually rich motif for Holy Saturday. Medieval illuminations, frescoes, and sculptures depict Christ breaking open the gates of Hell, leading a triumphant procession of patriarchs, including Adam, Eve, David, and John the Baptist. The 14th-century Anastasis fresco in the Chora Church (Istanbul) is a quintessential example, with Christ shown radiant in a mandorla, trampling the locks of Hades and grasping Adam and Eve by the wrists (Cormack 110–115). Western analogues include the Harrowing of Hell panels in the 12th-century Winchester Psalter and the Holkham Bible (c. 1327–35), where narrative illumination brings theological themes to life. In Giotto’s Descent into Limbo (c. 1304–06), painted for the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Christ’s compositional centrality and the emphatic gesture toward the just souls reinforce his salvific role.

The interplay between darkness and light is a recurring symbolic device in Holy Saturday art. Artists like Michelangelo and Caravaggio masterfully employed chiaroscuro to capture theological transition. Michelangelo’s The Entombment (c. 1500–01, National Gallery, London) is suffused with tension; Christ's lifeless body is lowered into the tomb, yet the composition's upward movement hints at eventual ascension (Hartt 214–217). Darkness envelops the scene, with subtle indications of light breaking through. The metaphor of Christ as light in darkness resonates with the Paschal Vigil and the Gospel of John (1:5): “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.”

In Orthodox Christianity, the Harrowing of Hell (Anastasis) is the central image of Pascha, and iconography reflects this doctrinal emphasis. The Eastern visual lexicon avoids depicting the crucifixion's suffering and instead focuses on resurrectional triumph. Icons from the 12th to 15th centuries show Christ dynamically rescuing the righteous from Sheol, surrounded by prophets and apostles. The figures are stylized, the colors vivid, and the spatial arrangements evoke heavenly transcendence. Bissera Pentcheva notes how these icons, particularly from the Macedonian and Paleologan periods, were designed to engage multiple senses through chant, incense, and procession (Pentcheva 94–98). The anastasis becomes a liturgical and aesthetic experience of cosmic victory.

While the Harrowing motif waned in prominence after the Reformation, Renaissance and Baroque artists continued to grapple with Holy Saturday’s themes. Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ (1603–04, Vatican Museums) emphasizes corporeality and emotional weight. The diagonal positioning of Christ’s body and the downward motion suggests burial, yet the intensity of light on the figures anticipates resurrection (Langdon 205–210). In Titian’s Pietà (1575–76), painted for his own tomb, the pathos and tension between death and divine mercy embody Holy Saturday’s emotional and spiritual ambiguity.

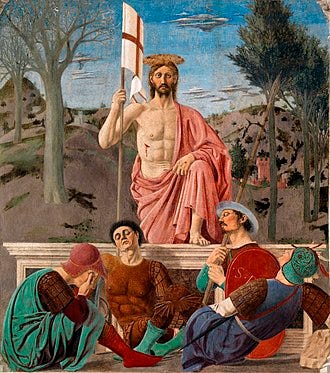

The Easter Vigil, rich in ritual symbolism, profoundly influenced Christian iconography. The ritual lighting of the Paschal candle, representing Christ’s light conquering darkness, is echoed in images that feature radiant halos or supernatural illumination. Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection (1460s, Museo Civico, Sansepolcro) captures this moment with calm grandeur: Christ emerges from the tomb at dawn, flanked by sleeping guards, as natural light floods the background. This visual language of awakening correlates with vigil readings from Genesis and Exodus, linking Christ’s resurrection to creation and liberation.

Despite its theological richness, Holy Saturday remains underrepresented in Christian art due to its narrative austerity. Exceptions appear in liturgical manuscripts and church sculpture. The tympanum at Vézelay Abbey (12th century) features Christ liberating souls; a rare monumental depiction of the Harrowing. The St. Albans Psalter (c. 1120–40) also includes visual references to the descent. These exceptions reveal a selective yet powerful visual engagement with Holy Saturday, particularly where theology demanded artistic amplification.

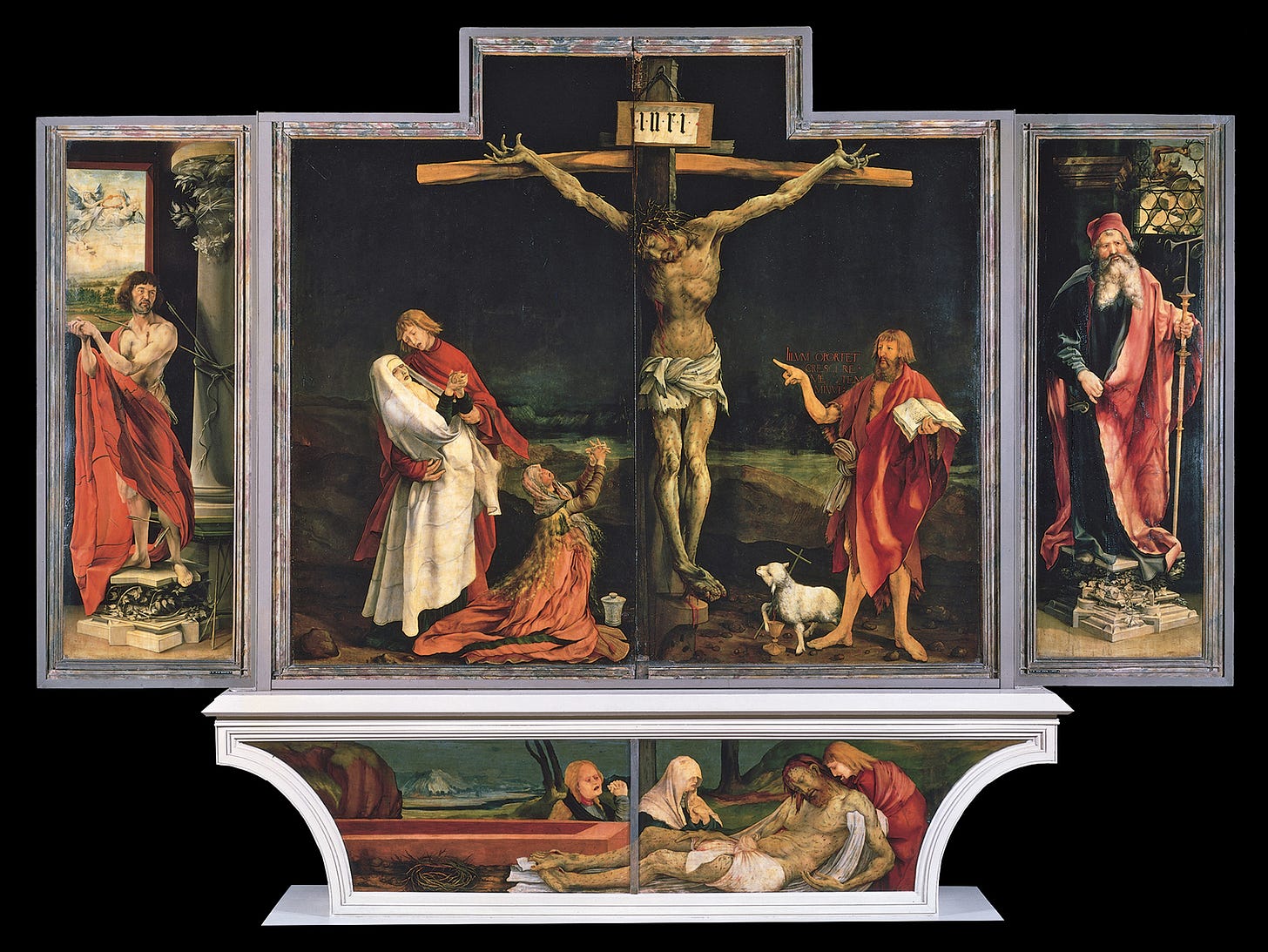

Artistic representations of Holy Saturday occupy a tonal midpoint. Good Friday’s art is raw and tragic; Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512–16) embodies grotesque suffering; while Easter art often bursts with triumph and color, as in Fra Angelico’s Resurrection of Christ and Women at the Tomb. Holy Saturday art is somber yet restrained. Its silence is often depicted through closed space, downcast figures, or barren landscapes. This restrained approach deepens its emotional resonance, drawing the viewer into contemplation rather than action.

Contemporary artists have embraced Holy Saturday’s themes through abstraction, performance, and multimedia. British-Indian sculptor Anish Kapoor’s void works, such as Descent into Limbo (1992), play with absence and interiority, reflecting theological emptiness. Makoto Fujimura, in his Silence and Beauty series, combines Nihonga materials with Christian iconography to depict waiting as spiritual discipline. Contemporary liturgical artists and video installations during Easter Vigil services also use slow pacing, minimal sound, and shifting light to evoke the passage from death to life.

Holy Saturday, often overlooked in both theology and art, offers a profound lens through which to explore Christian ideas of waiting, hope, and divine absence. From the triumphal images of the Harrowing of Hell in Byzantine icons to the psychological depth of Renaissance entombments and the abstract voids of modern sculpture, Holy Saturday's themes continue to inspire. The silence of the tomb, far from being empty, resounds with the promise of resurrection.

References:

Bradshaw, Paul F. The Origins of Feasts, Fasts, and Seasons in Early Christianity. Liturgical Press, 2011.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200–1336. Columbia UP, 1995.

Cormack, Robin. Byzantine Art. Oxford UP, 2000.

Hartt, Frederick. History of Italian Renaissance Art. Prentice Hall, 2002.

Kessler, Herbert L. Seeing Medieval Art. Broadview Press, 2004.

Langdon, Helen. Caravaggio: A Life. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999.

Lewis, Alan E. Between Cross and Resurrection: A Theology of Holy Saturday. Eerdmans, 2003.

Pentcheva, Bissera V. The Sensual Icon: Space, Ritual, and the Senses in Byzantium. Penn State UP, 2010.

Additional Sources: Jensen, Robin M. The Harrowing of Hell: A Visual Tradition. Fortress Press, 2021.

Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. 2: The Passion of Christ. Lund Humphries, 1972.

Weitzmann, Kurt. The Icon: Holy Images—Sixth to Fourteenth Century. George Braziller, 1982.

That Caravaggio is extraordinary!

Thank you! So interesting!!