Between the mid-1960s and early 1980s, LGBTQ artists and communities in New York City and beyond forged an insurgent aesthetic that rejected assimilation into mainstream institutions and instead claimed public space through posters, performance, video, sculpture, and, parallel to these, codified drag and voguing culture. Building on Stonewall’s revolutionary energy, these intertwined movements, Gay Liberation Art (c. 1970–1980) and the contemporaneous crystallization of ballroom and drag aesthetics, developed collective authorship, media appropriation, and unapologetic visibility as tools of resistance, self-creation, and community building.

The June 28, 1969, Stonewall uprising catalyzed both street-level protest and a burgeoning queer aesthetic. Gay Liberation Front (GLF) pamphlets invoked feminist and Black Power rhetoric, insisting that “the personal is political”, and urged queers to appropriate mass-media tools to resist state violence and build community . Jonathan Weinberg’s Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989 situates Gay Liberation Art within the broader sweep of post-1968 protest movements, demonstrating how artists swiftly adopted screen printing, Xerox, and Super 8 film to bypass gallery gatekeepers and circulate work through community centers, bookstores, and pride marches .

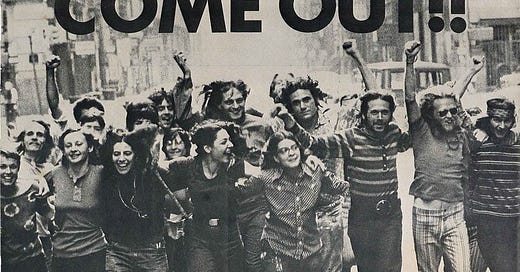

Poster-making became a cornerstone of Gay Liberation’s visual arsenal. In New York, the GLF’s 1970 “Come Out! Fight! Win!” poster, photographed by Peter Hujar, paired stark black-and-white portraiture with bold sans-serif typography, demanding queer visibility as protest (Gay Liberation Front) . In London, the U.K. GLF staged theatrical “zaps,” such as the 1971 Festival of Light interruption, converting homophobic lectures into spontaneous street theater via costumed interlopers and mass paste-ups (“Ball Culture”) . Simultaneously, Los Angeles’s Woman’s Building hosted the Lesbian Art Project (1977–1979), whose An Oral Herstory of Lesbianism anthology of text and image was photocopied and distributed at women’s centers nationwide .

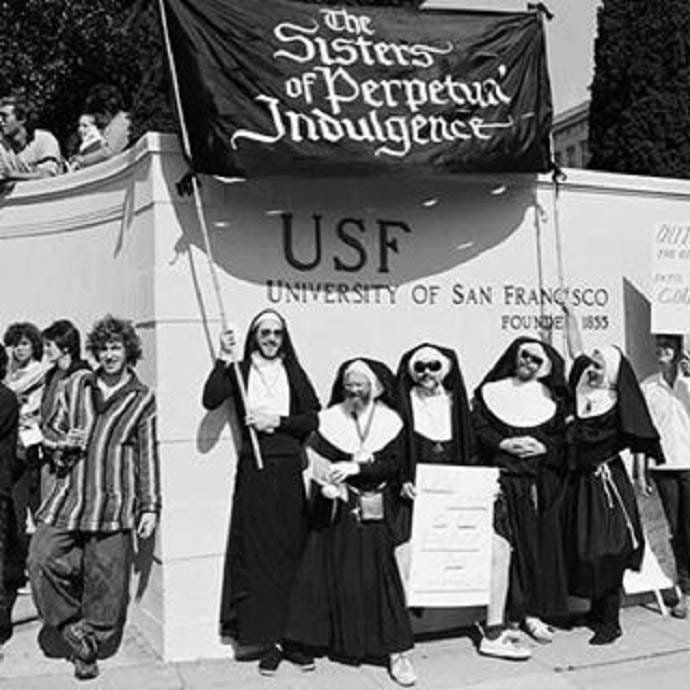

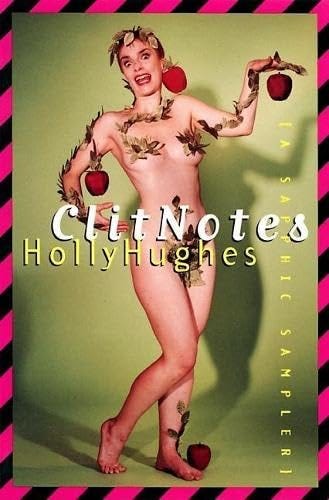

Performance foregrounded the body as political site. Stephen Varble’s “Trash Couture” actions (c. 1975–1977) saw him parade through Midtown Manhattan in sculptural garments made of refuse and drag, confronting audiences with simultaneous critiques of environmental neglect and queer erasure (Varble) . In San Francisco, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence (est. 1979) donned habits and clown makeup to parody religious authority, deliver AIDS education, and fund-raise, an early model of drag as radical street performance (“Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence”) . In New York, Holly Hughes’s one-woman shows at the Women’s One World Café, My Life as a Glamour Don’t (c. 1980) and later Clit Notes (1996), wove camp, autobiography, and lesbian eroticism into feminist critique, prefiguring NEA controversies (Hughes) .

Portable video democratized queer media. The Videofreex collective (1969–1978) captured both liberatory street actions and intimate portraits in their 1976 short Gay for a Day, positing queer joy and protest as inseparable (Videofreex) . On the West Coast, Barbara Hammer’s 1975 film Dyketactics used montage and voice-over to assert lesbian identity as radical performance (Hammer). Concurrently, New York’s Women’s Interart Center (est. 1971) offered video workshops led by Susan Milano, enabling women and lesbians to appropriate broadcast aesthetics for grassroots organizing (“Women’s Interart Center”) .

By 1980, queer artists claimed public form. George Segal’s Gay Liberation (1979–1980), sited in Christopher Park opposite the Stonewall Inn, was the first U.S. monument to honor same-sex affection: four life-size white-bronze figures, two male, two female, in tender embrace, directly contesting heteronormative norms of public display (Segal). Abroad, Rosa von Praunheim’s 1971 film It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives screened at MoMA and the Berlin International Film Festival, spurring German gay-rights activism alongside poster campaigns and public debate (von Praunheim).

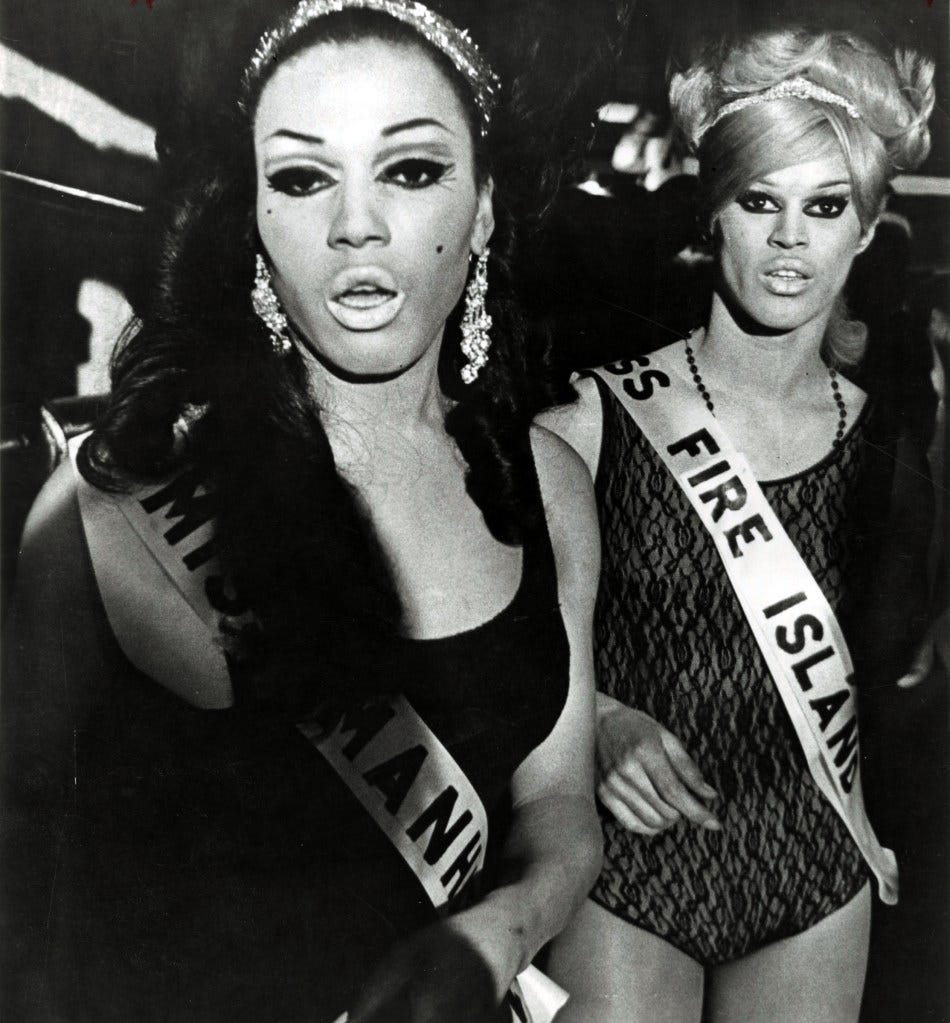

In parallel, New York’s ballroom culture crystallized into a rigorously codified performative subculture. Predominantly Black and Latinx LGBTQ people formed “houses”, chosen families led by “mothers” and “fathers”, to provide mutual support and identity amid racism and homophobia (Peabody Ballroom Project) . Houses such as LaBeija (1968), Xtravaganza (1974), Aviance (1979), and Ninja (mid-1970s) collaborated on DIY couture, choreographed group walks, and designed flyers that became ephemeral artifacts of resistance (Samuels) .

By the early 1970s, ballroom categories were rigorously defined. “Realness” categories tested contestants’ ability to pass as mainstream archetypes, businesspeople, military officers, or runway models, while “Femme Queen Realness” celebrated hyper-feminine drag performance (Ball Culture) . “Vogue” dancers translated static poses from Vogue magazine into kinetic sequences of spins, dips, and sharply angled hand gestures. Scholars distinguish “Old Way” voguing (pre-1981), characterized by rigid lines and floor work, from later “New Way” and “Vogue Femme,” which introduced fluid contortions and elaborate dramatics (Jackson 30) .

Ballroom performers mastered an ethos of camp and extravagance: runway walks fused model poise with theatrical flair; mid-floor costume changes showcased ingenuity in repurposed garments; judges assessed “charisma,” “uniqueness,” and “nerve” as much as technical skill (Grinnell College Subcultures Project) . Camp’s irony and parody, rooted in drag tradition, enabled participants to critique both heteronormative and racist cultural norms while forging collective joy (“The Ballroom Scene”) .

Willi Ninja (1964–2006) coined “voguing” and pioneered the “butch queen” aesthetic and hand-performance techniques exemplified in his 1979 piece “Shimmy,” documented in community newsletters like Marcel Christian’s Idle Sheets (Ninja) . Costume designer Howard Crabtree’s theatrical drag couture for the stage piece Home Movies (1979) exemplified the DIY elegance of ballroom fashion, as documented in his costume-design papers at the New York Public Library (Crabtree) .

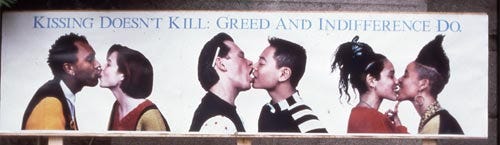

Although Gran Fury formally emerged in 1988, its graphic insurgency, most notably Kissing Doesn’t Kill (1989), drew directly from Gay Liberation poster tactics, repurposing Marlboro-style ads to critique media silence around AIDS (Gran Fury) . The Lesbian Art Project’s participatory archiving anticipated ACT UP’s billboard takeovers and gallery installations documenting the pandemic’s devastation. Holly Hughes’s ongoing blend of autobiography, satire, and bodily display in Clit Notes (1996) underscores the through-line from Stonewall’s insurgent ethos to the culture-war flashpoints of the 1990s (Hughes) .

Between 1970 and 1980, LGBTQ communities in New York and beyond erected a radical visual and performative lexicon. From photocopied manifestos and guerrilla poster campaigns to video manifestos, public monuments, and codified drag battles, these intertwined movements insisted on queer humanity as a political force. Their legacy endures,.in contemporary murals, digital flash mobs, runway shows, and film, reminding us that art and performance remain vital frontlines in the ongoing struggle for sexual and gender justice.

References:

Ball Culture. Ball Culture. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.

Gran Fury. Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do. Poster series, 1989.

Hammer, Barbara. Dyketactics. Film, 1975.

Hughes, Holly. My Life as a Glamour Don’t. Performance, Women’s One World Café, New York, c. 1980.

Jackson, Sherry Thomas. Strike a Pose, Forever: The Legacy of Vogue and its Recontextualization. European Journal of American Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 2017, pp. 26–42.

Lesbian Art Project. An Oral Herstory of Lesbianism. Photocopied anthology, Woman’s Building, Los Angeles, 1979.

Ninja, Willi. Shimmy. Performance, New York City, 1979. TGI Archives.

Peabody Ballroom Project. Ballroom History. Johns Hopkins University, 2023.

Praunheim, Rosa von. It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives. Bavaria Film, 1971.

Segal, George. Gay Liberation. White bronze sculpture, Christopher Park, New York, 1979–1980.

Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. Performance collective, San Francisco, est. 1979.

Videofreex. Gay for a Day. 16 mm film, 1976.

von Praunheim, Rosa. It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives. Film, 1971.

Varble, Stephen. Trash Couture performances, Midtown Manhattan, 1975–1977.

Weinberg, Jonathan, editor. Art After Stonewall, 1969–1989. Rizzoli, 2019.

Women’s Interart Center. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation.