Oscar Wilde emerged in late Victorian London “as the living embodiment of the Aesthetic movement,” promoting l’art pour l’art and a flamboyant dandyism that defied puritanical norms. His aphorisms and flamboyance made him a target of moral censure, yet his insistence on beauty and pleasure as life’s guiding values challenged the era’s sexual and artistic orthodoxy. Wilde’s art-for-art’s-sake ethos rejected utilitarian morality and turned Victorian social norms on their head. As the Encyclopedia Britannica notes, Aestheticism insisted that “art exists for the sake of its beauty alone” and “need serve no political, didactic, or other purpose”. Wilde internalized these ideas in life and work, embodying an aesthetic defiance of strictures against homosexuality. Indeed, his personal style, effeminate dress, sharp wit, devotion to beauty, made him a symbol of queerness itself, a “living embodiment” of aestheticism whose art and life “formed a formidable challenge to Victorian puritanicalism”. After his trial and imprisonment for “gross indecency,” Wilde became a martyr-figure of queer culture, canonized in modern memory. The “moral panic” over Wilde’s sexuality served only to cement his legend as a champion of personal and artistic freedom.

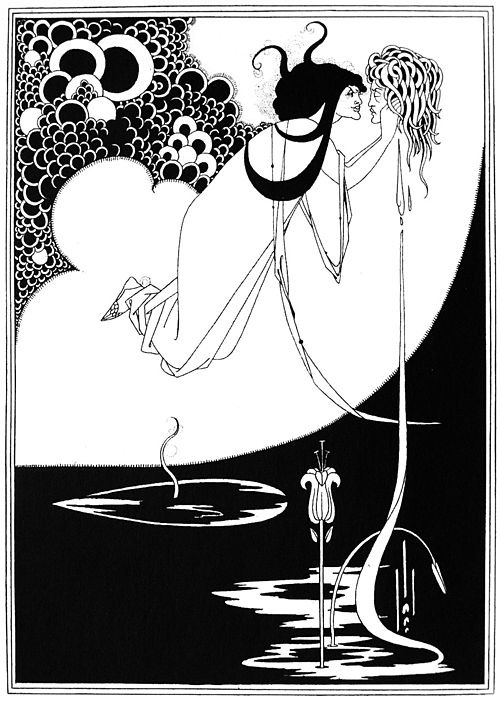

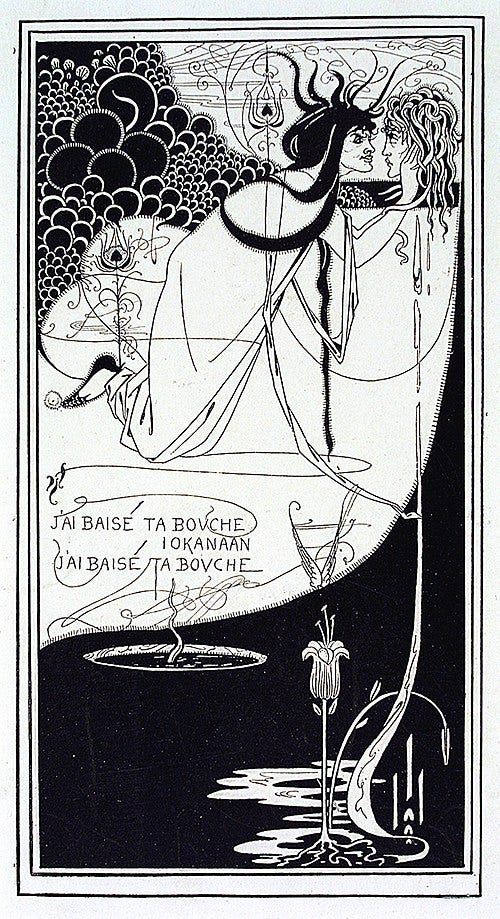

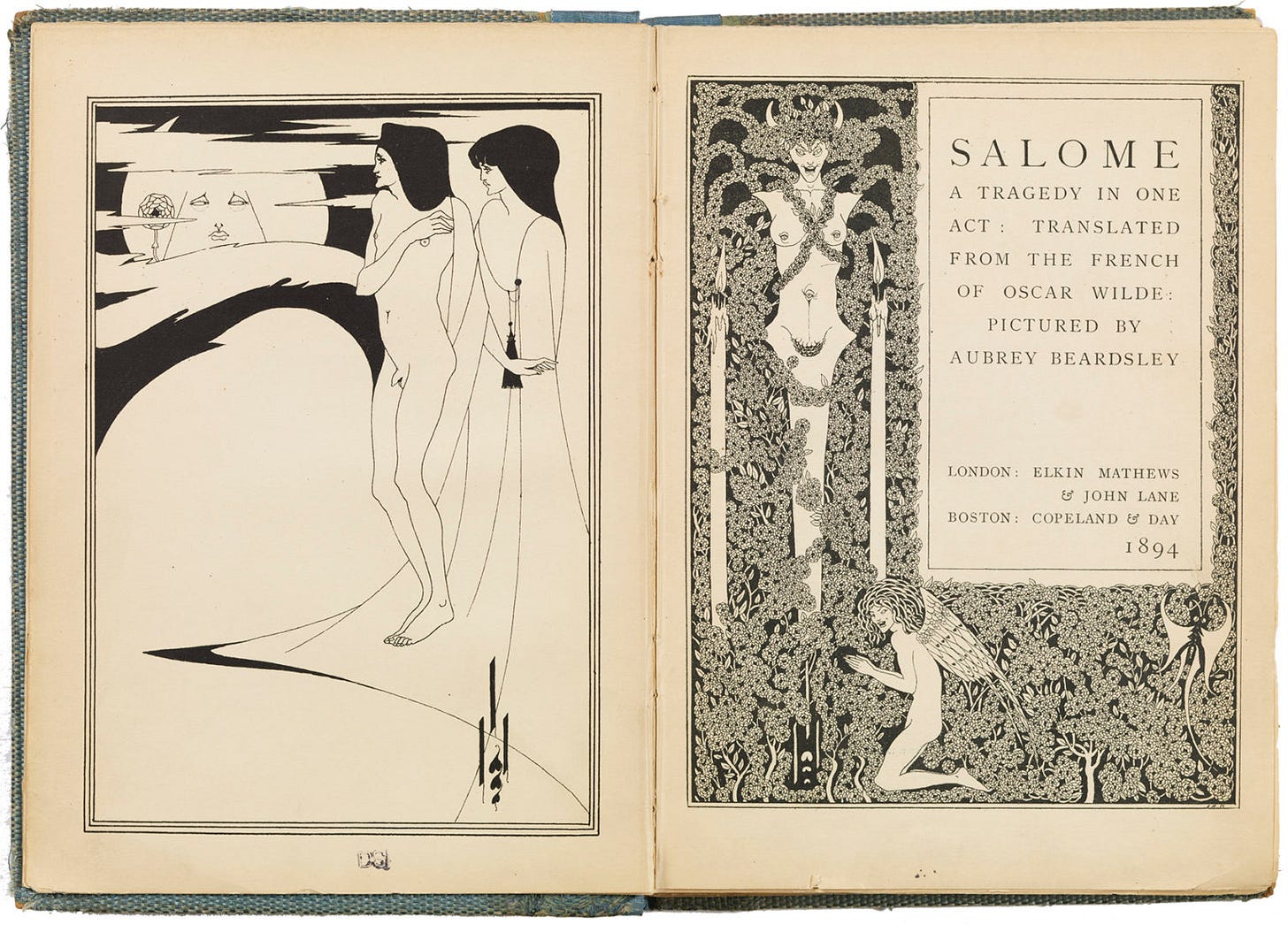

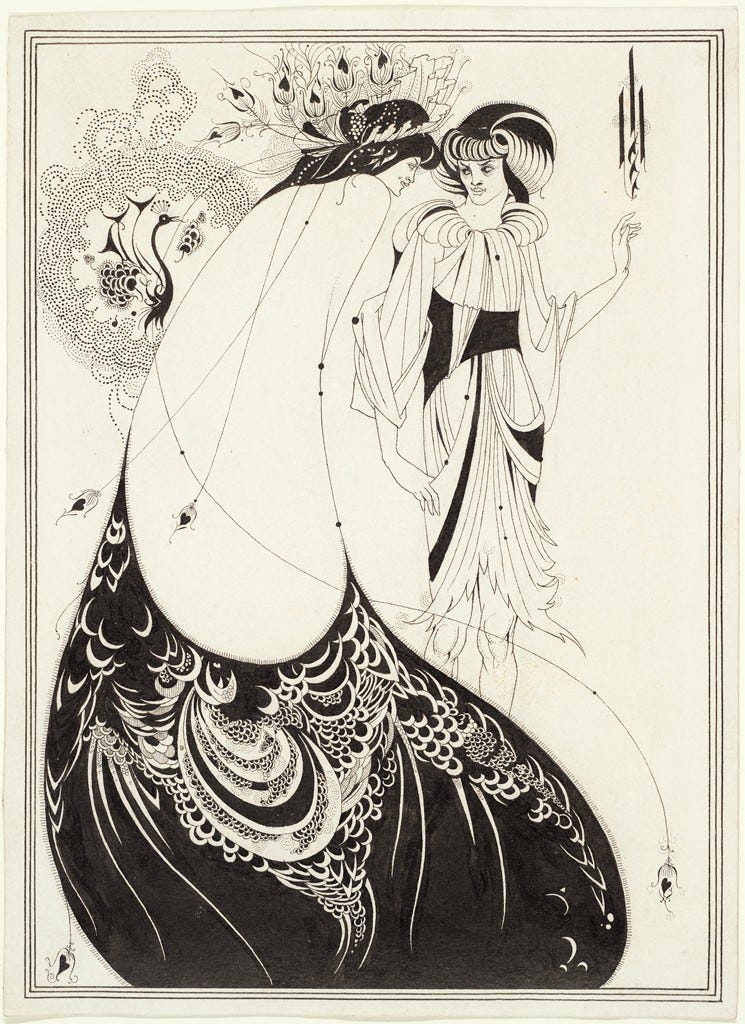

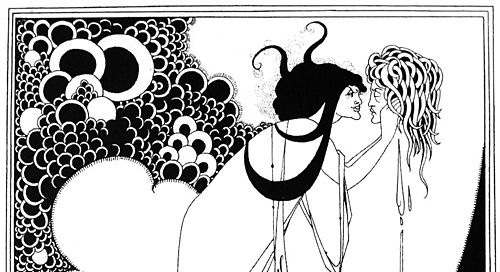

Wilde’s circle included The Yellow Book illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, whose 1893–94 illustrations for Salomé remain iconic. Beardsley’s stark black-and-white drawings for Wilde’s play blend exotic sensuality with grotesquery, creating a “disturbing framework” of cruelty, eroticism, and “deliberate ambiguity and blurring of gender”. Cooper Hewitt curator Matthew Kennedy observes that Beardsley’s Salomé imagery features “sexually assertive women and androgynous figures [that] represented new identity types in fin de siècle culture”; figures which defy the rigid gender polarity of Victorian society. In Beardsley’s work, heterosexuality is “one of many possibilities,” and gender boundaries are deliberately blurred into “fantastical androgyny”. In short, his illustrations queered Wilde’s play, as Kennedy writes, Beardsley’s visual style is itself “a queering of Victorian values,” supplementing Wilde’s textual themes by highlighting “transgressive sexual desires” and collapsing the traditional gender binary.

Beardsley’s aesthetic also pushed queer subtext through its exaggerated decadence. Donald Olson notes that many of Beardsley’s drawings have a grotesque, “diabolical subtext”; the artist himself quipping “If I am not grotesque, I am nothing”. His sinuous, black-ink figures (such as the peacock-skirted Salomé and her severed head) scandalized Victorian audiences. Yet these images implicitly challenge Victorian sexual morality: in Salomé, for example, Wilde’s own character of Jokanaan (John the Baptist) proclaims “By woman came evil into the world,” a line that Beardsley’s art undercuts by fetishizing Salomé’s, and indeed male, desire. Scholars have even drawn a parallel between Salomé’s illicit fascination with Jokanaan and Wilde’s “love that dare not speak its name,” given that both narratives dramatize forbidden desire under repressive laws. In sum, Beardsley’s partnership with Wilde exemplified aesthetic decadence “queer in the sense that it continually crosses genders and sexualities”, visually enacting the very subversion of Victorian gender norms that Wilde celebrated.

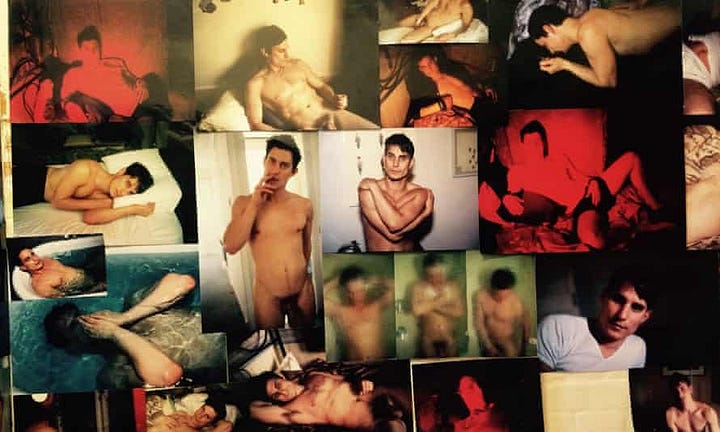

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, several prominent visual artists have explicitly invoked Wilde’s aesthetic spirit and themes in queer-inflected works. In 2016, the London arts organization Artangel mounted Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, an exhibition staged in the cells of the former Reading Gaol (where Wilde was incarcerated) that featured work by Marlene Dumas, Nan Goldin, Steve McQueen, Wolfgang Tillmans, and others. Each artist grappled with Wilde’s legacy in their medium. Photographer Nan Goldin, for instance, created an installation around Wilde’s old cell and curated excerpts from Salomé and Genet’s Un Chant d’Amour. Goldin has long cited Wilde as a formative influence: she told The Guardian that Wilde taught her “you can be who you pretend to be. You can remake yourself completely,” an idea that drove her own self-creation through art. In the Reading Prison project, Goldin included a video interview with a man seeking posthumous apology for a gay conviction, and she refers to Wilde’s “love that dare not speak its name” in curating images. She describes how she and her circle “worshipped Wilde”, “we read everything we could” of him, noting that it was Wilde’s flamboyance, wit and style that most deeply affected her, shaping not only her creative voice but her attitude toward life.

Marlene Dumas similarly engaged with Wildean themes in her art. In Inside, she exhibited diptych portraits of Wilde and his lover Lord Alfred Douglas (“Bosie”). Art critic Sue Hubbard notes that Dumas’s portraits of Wilde and Bosie act as “stark reminders” of the hypocrisy between Victorian public respectability and hidden queer lives. Dumas paints Wilde ethereally and Douglas demonic, unpacking “notions of complicity and victimhood” in their doomed relationship and suggesting that in a more tolerant age “Wilde could simply have been himself”. The Inside show even highlighted Dumas’s piece where Wilde and Bosie are “reunited in a diptych” of tabloid caricatures (one cell held a large gold-painted mosquito net by McQueen; an adjacent cell displayed a Dumas diptych of Wilde and Bosie). Overall, Dumas’s work combines the personal and political, by painting Wilde and Bosie as iconic queer martyrs, she extends his critique of moral orthodoxy into contemporary dialogue on identity, gender and public/private life.

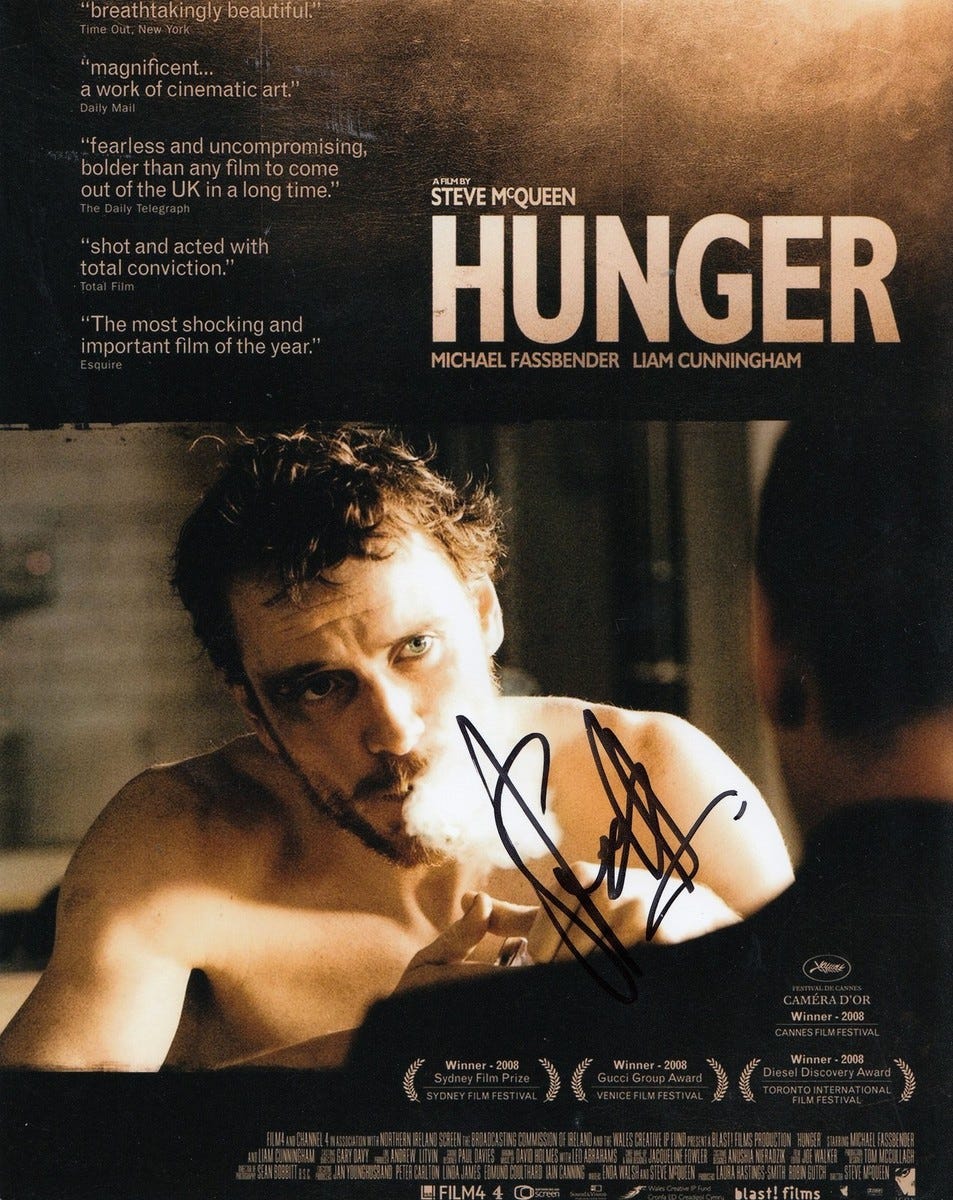

British artist (and filmmaker) Steve McQueen contributed a sculptural installation to the same project. In one Reading Gaol cell he draped a gold-plated mosquito net over the prison bunk bed, a ghostly cocoon that invokes both brutality and opulence. McQueen’s art often explores power, labor and identity (his films Hunger and Shame are critical portraits of gay subjectivity), and in Inside his gilded net references the colonial commodity (sugar) brought by indentured West Indian laborers, a subtle parallel to Wilde’s imprisonment for the “crime” of homosexuality. The Inside guide notes McQueen’s background as a Turner Prize-winning filmmaker and conceptual artist, and his historical engagement with resistance (e.g. Caribs’ Leap, Western Deep). By placing his work in Wilde’s own cellblock, McQueen underscores the idea that aesthetic beauty (a mosquito net) can exist amid institutional cruelty, a poetic nod to Wildean paradox.

Wolfgang Tillmans, a German-born photographer known for intimate queer imagery, also participated. Though he did not install a new piece in 2016, he contributed to Inside by exhibiting a large self-portrait shot into a broken mirror found in the prison. Tillmans’s practice, as Artangel notes, “pairs intimacy and playfulness with social critique and the persistent questioning of existing values and hierarchies”. (He had previously made a similar fractured mirror portrait in 1990.) In a broader sense, Tillmans, whose photographs of queer life and youth culture have been internationally celebrated, embodies Wilde’s aesthetic of personal image-making; his work collapses public and private, art and documentation, echoing Wilde’s own persona as living art. Though less explicitly about Wilde, Tillmans’s participation in Inside places his intimate, morally-challenging vision in direct dialogue with Wilde’s legacy of aesthetic dissent.

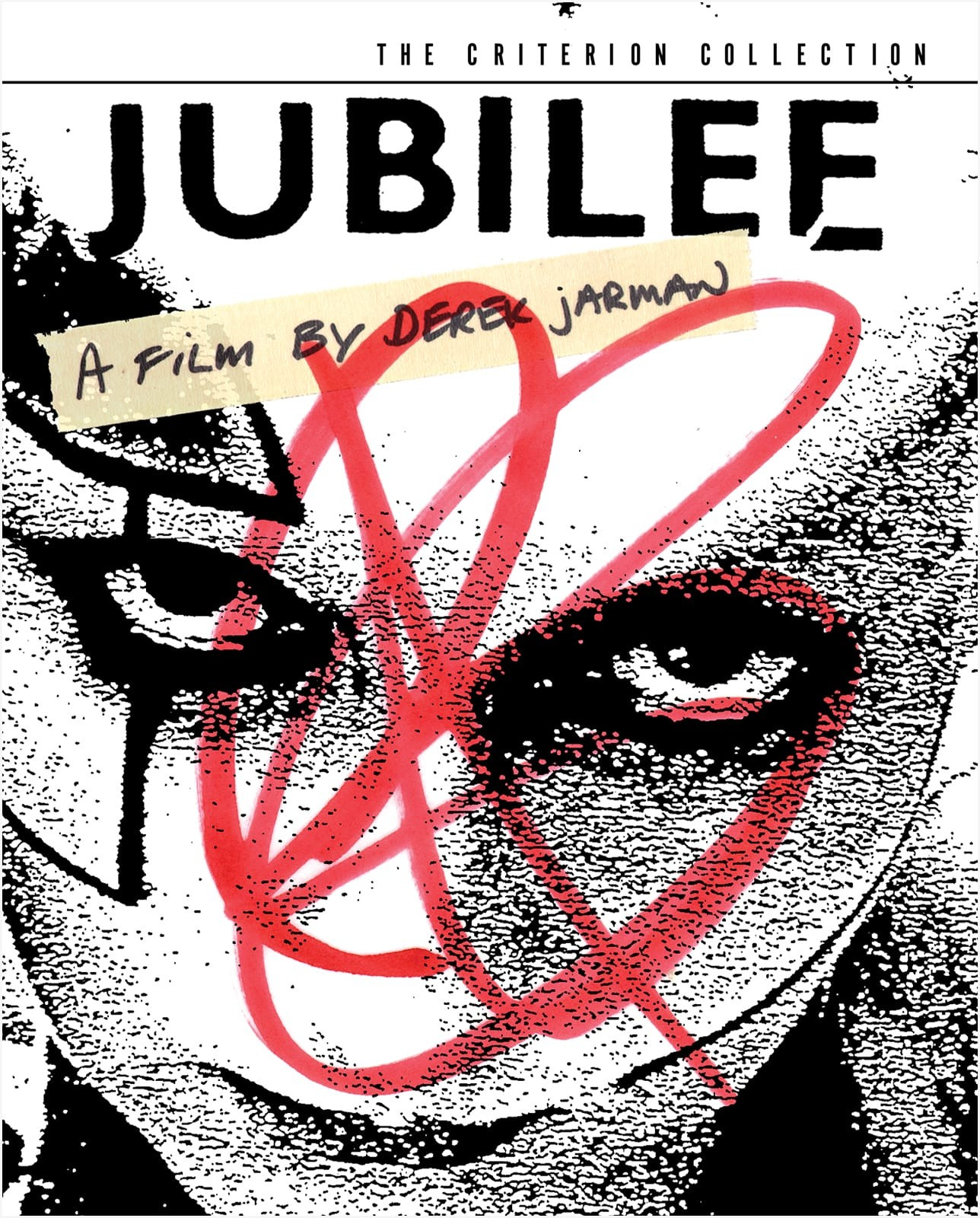

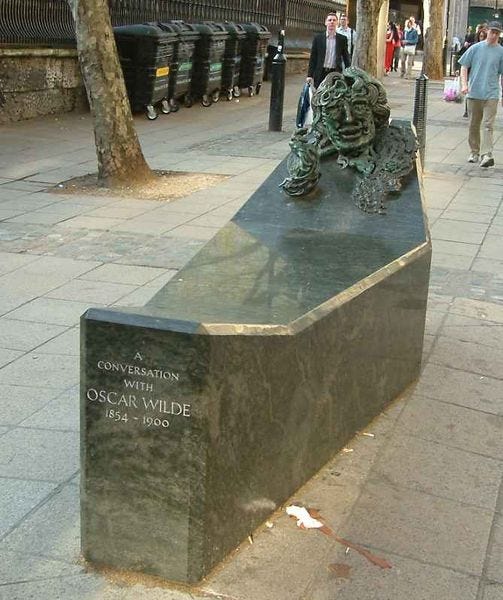

Derek Jarman (1942–1994) – the British film director turned painter and installation artist; was one of the earliest contemporary figures to valorize Wilde’s life and image. Jarman was openly gay and worked at the forefront of queer art in the 1970s–90s; he directed the first biopic of a gay martyr (his 1977 Jubilee featured a scene with a dying Queen Victoria imagining young Oscar Wilde) and his final major film Wittgenstein (1993) cast Wilde’s intimate group of friends. But Jarman’s visual art and activism also carried a Wildean stamp. The Independent notes that it was Jarman’s dying wish to see a statue of Wilde erected in London. He long campaigned for such a memorial, co-founding (with others) a group to raise funds and select a design. (The result Maggi Hambling’s green bench-sarcophagus statue, was unveiled in 1998, two years after Jarman’s death.)

In his own paintings and mixed-media work, Jarman often quoted Wilde and evoked Victorian iconography. For example, a 1989 mixed-media assemblage titled Household God V (Molière) famously features a handwritten Wilde quotation from De Profundis: “The faith that others give to what is unseen, I give to what one can touch and look at”. This line, about valuing tangible, sensual experience over metaphysical creed, captures both Wilde’s and Jarman’s materialist aesthetics. More broadly, Jarman’s late paintings (often large canvases splattered with bright tar and pigment) draw on symbols like boats, tombs, and angels in ways that recall Wilde’s spiritual and romantic questioning. Art historians have described Jarman’s art as blending camp wit with ache, an “archaeology” of queer history. While explicit critical writing on Jarman directly invoking Wilde is scant, his career-long idolatry of Wilde is clear: as Goldin remarked, she and her generation “worshipped Wilde” for his attitude and style, and Jarman was of that ilk. In sum, Jarman’s visionary queer art, like Wilde’s, mixed beauty with defiance, martyrdom with play, and helped cement Wilde’s enduring resonance in queer visual culture.

Across more than a century, Oscar Wilde’s aesthetic and ethical provocations have proved fertile ground for queer artists. From Victorian book illustrator to modern gallery, Wilde’s ethos of beauty over morality continues to inspire work that subverts norms. Beardsley’s decadent, gender-queer drawings for Salomé set an early precedent, consciously “queering” a biblical tale and Victorian art itself. In recent decades, artists of diverse media, painters like Marlene Dumas, photographers like Nan Goldin and Wolfgang Tillmans, filmmakers like Steve McQueen and Derek Jarman, have explicitly acknowledged Wilde’s influence. Whether by recreating Wilde’s visage or words, staging queer narratives in his former cell, or simply echoing his rebellious spirit, these artists reinforce Wilde’s status as an icon of artistic freedom and queer identity. In each case, they highlight how Wilde’s “glittering talent” and defiant persona continue to animate contemporary explorations of identity, desire, and resistance. In the interplay of art history and queer theory, Wilde stands as a nexus: his life and work, once vilified, now offer a model of how beauty and dissent can intertwine to challenge any age’s moral conventions.

References:

Barker, Vicki. Reading Gaol, Where Oscar Wilde Was Imprisoned, Unlocks Its Gates For Art. NPR, 20 Oct. 2016. .

Goldin, Nan. Interview by Sean O’Hagan. The Guardian, 5 Sept. 2016. Nan Goldin: banged up in Reading gaol with Oscar Wilde.

Hubbard, Sue. Marlene Dumas: Oscar Wilde and Bosie – Significant Works. Artlyst, 18 Dec. 2021.

Kennedy, Matthew J. There’s Something About Salome. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 22 June 2021.

Olson, Donald. The Fall of Aubrey Beardsley. The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, vol. 27, no. 4, July–Aug. 2020, pp. –, glreview.org/article/the-fall-of-aubrey-beardsley. .

The Inside Project: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison. Artangel, 2016, artangel.org.uk/project/inside.

Wilde, Oscar. De Profundis. Penguin Classics, 2005.

Wollen, Peter, editor. Oscar Wilde and Modern Culture: The Making of a Legend. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Wilde at heart (review of Maggi Hambling’s Wilde exhibition). The Independent, 22 May 1997. Andrew Lambirth, Wilde at heart.

It seems the argument between art as aesthetic and art for art sake, encompassing political purpose—this battle has gone on a lot longer and more in-depth than many would care to admit. The struggle between coded imagery and Victorian culture would be comedic in today’s terms. It seems the curse of isolated spaces our publications is everyone had too much time to dwell on them! Like the walls of the prison, if you paste enough bodies in a pattern, soon they aren’t individual things any longer. They become averages. Normalized.

This is the fear of the extreme conservative and fundamentalist—the normalization of what is going on anyway!