In the decades following Abstract Expressionism, American art was propelled by cycles of rebellion and renewal. From the 1950s onward, artists broke away from previous paradigms, embracing popular culture, reductive forms, the natural landscape, ideas over objects, and new media, to challenge established definitions of art.

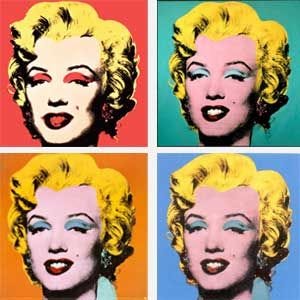

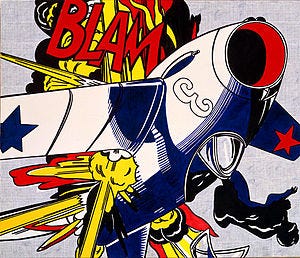

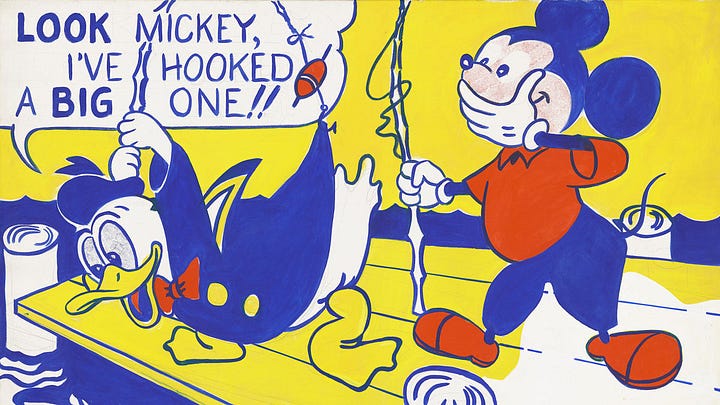

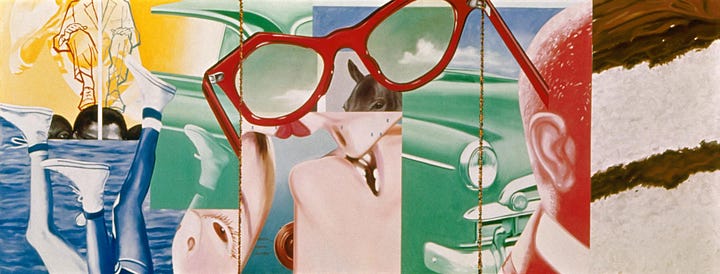

Pop Art exploded onto the scene in the late 1950s and 1960s as a direct challenge to the high-brow seriousness of earlier modern art. Originating in Britain and quickly embraced in the United States, Pop artists drew their subjects from advertisements, comic books, consumer products, and celebrities; the vivid stuff of mass media. By incorporating popular imagery into fine art, they blurred the boundary between “high” and “low” culture, rebelling against the elitist notion that only certain subjects or styles were fit for art. American Pop artists like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Claes Oldenburg became the movement’s most famous champions. They favored flat, graphic painting techniques, mechanical reproduction, and deadpan irony; strategies that “presented a challenge to traditions of fine art” by treating “mundane mass-produced” visuals as worthy subjects. For example, Warhol’s canvases of Campbell’s Soup cans and Lichtenstein’s comic-strip panels elevated everyday commercial images to the status of museum art. Pop Art’s cool detachment and penchant for kitsch also marked a rebellion against Abstract Expressionism’s emotional intensity: as one account notes, whereas the Abstract Expressionists mined the soul for trauma, “Pop artists searched for traces of the same trauma in the mediated world of advertising, cartoons, and popular imagery”. By the late 1960s, Pop Art had become one of the most recognizable styles of modern art, its bold appropriation of popular culture a symbol of postwar optimism and critique in equal measure.

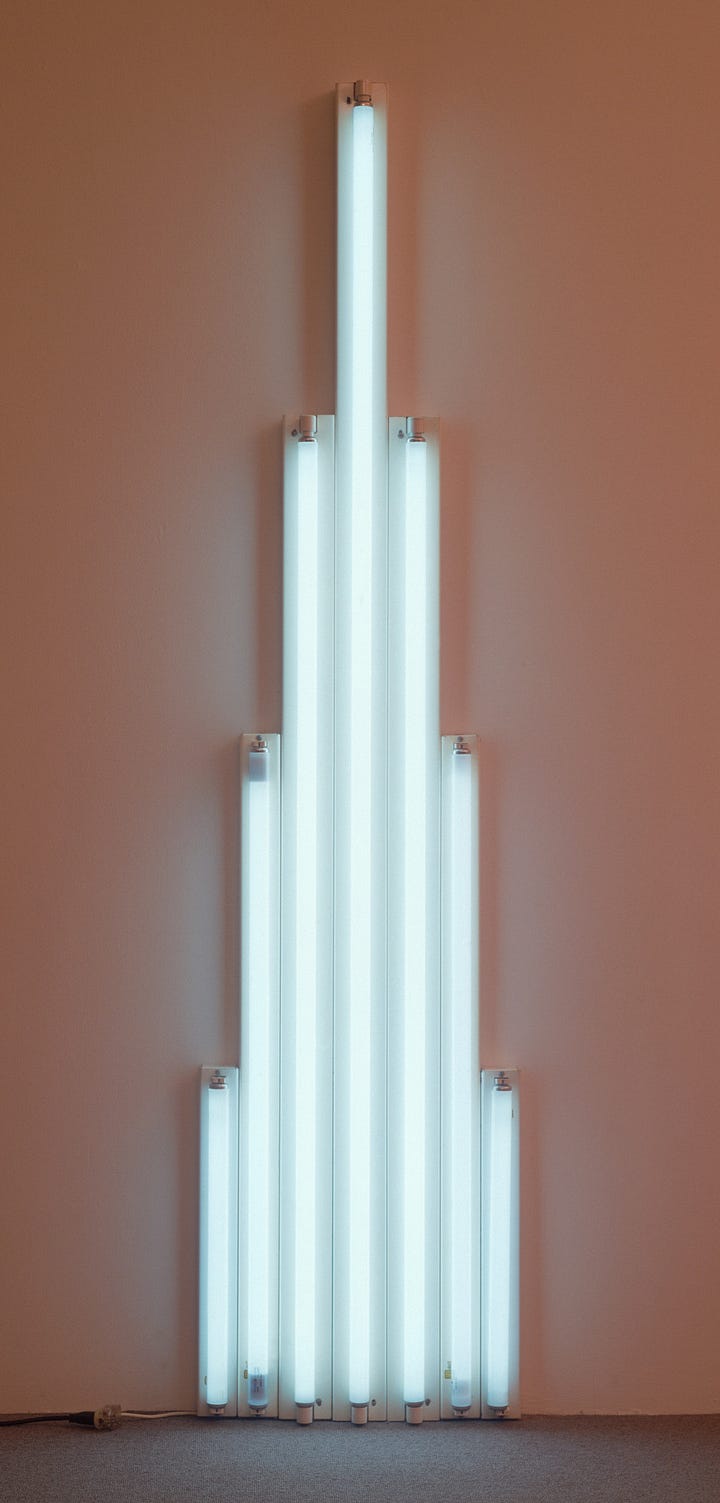

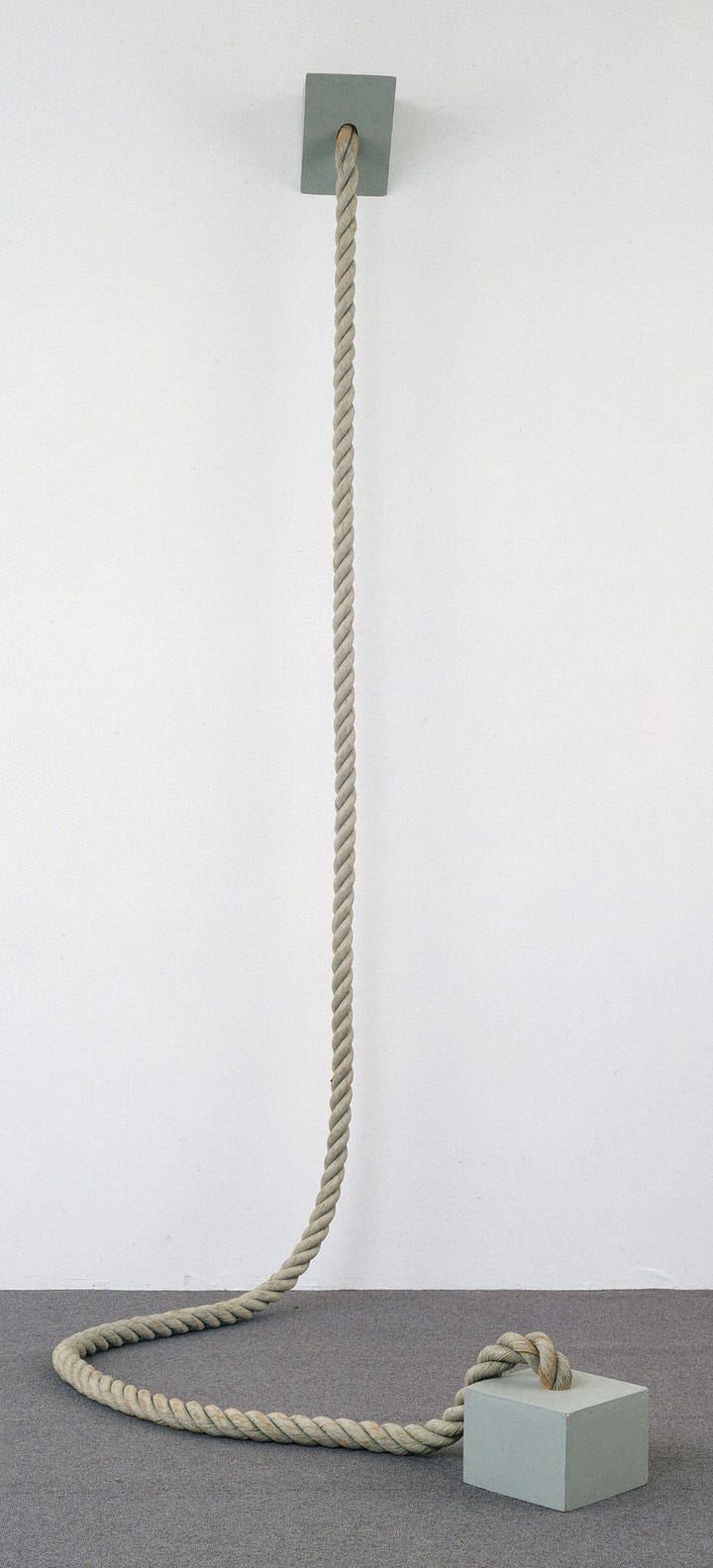

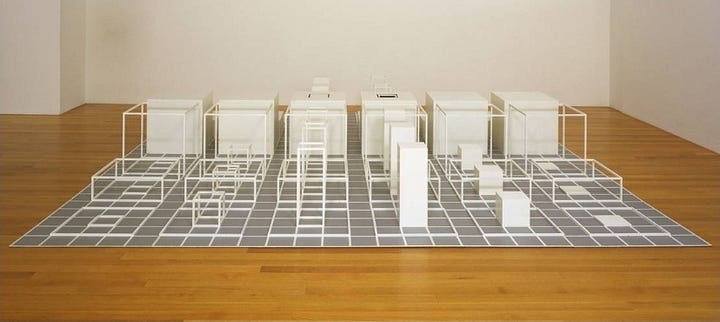

In stark contrast to Pop’s colorful consumer imagery, Minimalism arose in 1960s New York as a revolt against both Abstract Expressionism’s emotional drama and traditional craftsmanship in art. Minimalist artists pared art down to its essentials of form, material, and space, rejecting personal expression and illusion. In lieu of painted gestures or figurative imagery, they presented “literal” geometric structures, simple cubes, grids, and repeated units, often fabricated from industrial materials like steel, fluorescent light tubes, or bricks. This movement was explicitly interpreted as a reaction against Abstract Expressionism and modernism. Pioneers such as Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, Robert Morris, and Agnes Martin created works that “omit any extra-visual association” and refer to nothing outside themselves. For example, Judd’s rectangular plywood boxes and Flavin’s neon light installations are simply what they are, objects or lights in space, thereby “stripping away conventional characterizations of art” and forcing viewers to confront the pure experience of form. This cool, impersonal approach was rebellious in its austerity; Minimalism renounced the artist’s hand and the art market’s emphasis on unique, emotive masterpieces. Instead, it offered “a reaction to abstract expressionism” that declared art should be nothing more than itself. By reducing art to basic elements, Minimalism in effect renewed modern art’s vocabulary, introducing the gallery public to pristine blank canvases, mirror cubes, and fluorescent-lit rooms that challenged perceptions of space and objecthood.

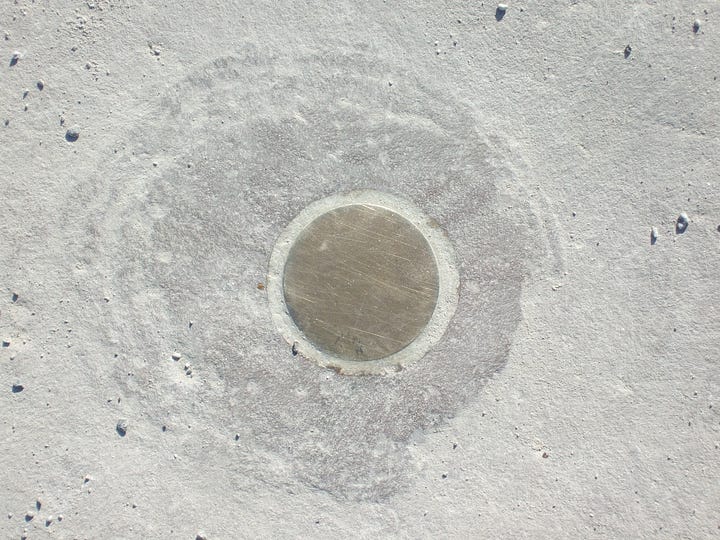

Amid late-1960s counterculture and ecological awareness, some American artists literally moved art out of the studio and into the land. The Earthworks (Land Art) movement sought to create monumental sculptures in remote natural sites, using the Earth as canvas and medium. This expanded the boundaries of art in radical ways: artists like Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Michael Heizer, and Walter De Maria sculpted deserts, lakeshores, and fields with soil, rocks, and other on-site materials. By doing so, they rebelled against the commodification of art and the confines of museums and galleries. Large-scale works such as Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (a giant rock spiral built in a Utah salt lake) and Heizer’s Double Negative (a pair of massive trenches cut into a Nevada mesa) could not be bought or easily exhibited; they exist in nature, often far from population centers. This anti-commercial stance was central to Land Art; the movement explicitly arose from a “rejection of the commercialization of art-making” and an enthusiasm for newly emergent environmental consciousness. The art often required photographic documentation for urban audiences, but the works themselves were site-specific and sometimes ephemeral (eroding with weather and time). Land artists also viewed their interventions as a return to primal or spiritual connections with the Earth; their renewal of art’s scope paralleled rising 1970s concerns with ecology and “the planet Earth as home to humanity”. By the 1970s, iconic Earthworks like Spiral Jetty had redefined sculpture, expanding it into the environment, and underscored a rebellious refusal to treat art as a portable commodity. This art-making “outside” signaled a profound renewal; galleries now had to consider maps and mud as much as marble and paint.

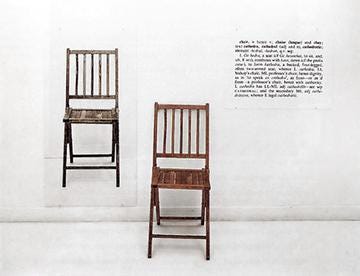

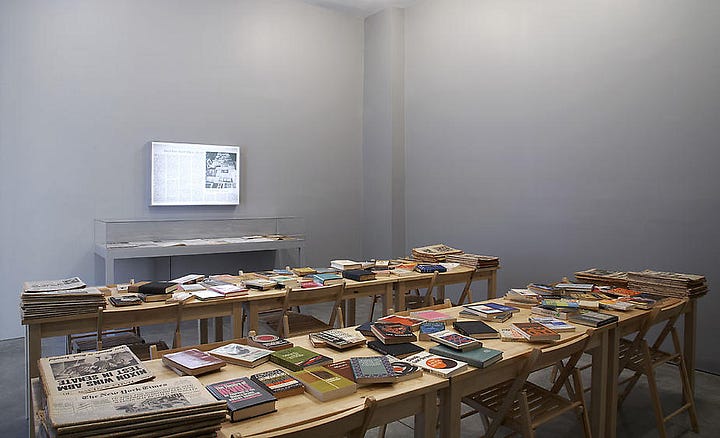

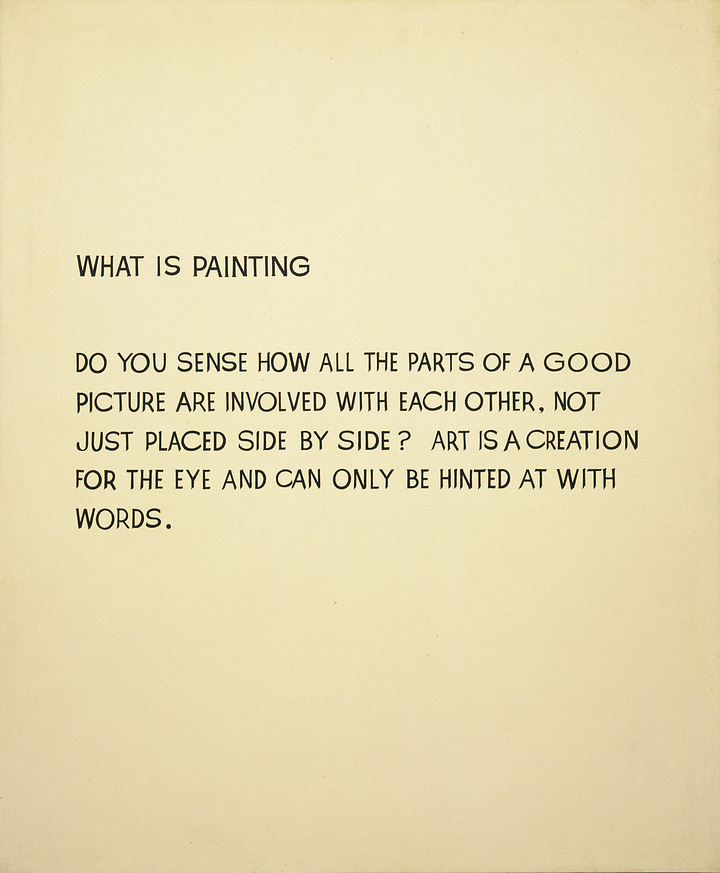

By the late 1960s, a provocative idea had gained currency; what if the idea behind a work mattered more than its physical form? This question drove the rise of Conceptual Art, a movement that prized concepts over traditional aesthetics or materials. In Conceptual Art, “the concept(s) or idea(s) involved in the work are prioritized equally to or more than the finished art object”. Early Conceptualists, including Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, John Baldessari, and the Art & Language group, produced art in the form of written statements, instructions, documented actions, or simple readymade objects. They radically asserted that the invisible idea itself is the true artwork, while any tangible output is secondary. This was a bold rebellion against the commercial art market and the notion of the artist as craftsman. As one summary notes, Conceptual Art “originated in the mid-to-late 1960s, and prizes ideas (concepts) over the aesthetic and commercial properties of artworks”. Many Conceptual works were deliberately dematerialized, for instance, Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965) presents an actual chair, a photo of that chair, and a dictionary definition of “chair,” prompting viewers to consider the concept of “chairness” rather than admire a handcrafted object. Instruction-based art (like LeWitt’s written directions for wall drawings) allowed works to be executed by others or merely imagined. Such strategies questioned authorship and the preciousness of art objects, aligning with the era’s anti-materialist, anti-institutional ethos. Conceptual artists often issued biting institutional critiques as well, exposing the political and economic structures of the art world within their work. While critics accused Conceptual Art of being esoteric or “elitist” intellectual games, its influence has been profound. It renewed art by expanding it into philosophy, language, and action, opening the door to installation, performance, and socially engaged art that followed. In essence, Conceptual Art in the 1960s–70s completed the rebellion begun by Duchamp’s readymades: it declared that the mind of the artist is the true site of art, not the canvas or sculpture displayed in a gallery.

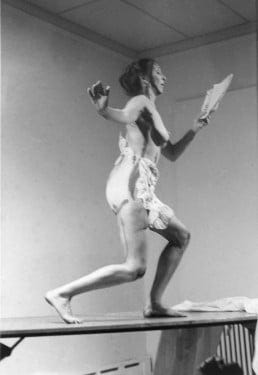

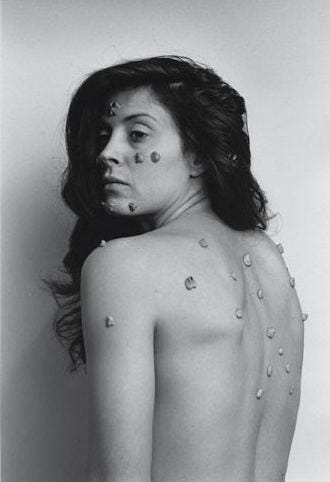

In the 1960s, many artists began to experiment with art forms that unfold in time and action, giving rise to the twin phenomena of Performance Art and Video Art. These new media represented a rebellion against static, saleable art objects and an embrace of ephemeral experience. Performance Art is broadly defined as “an artwork or art exhibition created through actions executed by the artist or other participants”, which may be live or documented. It emerged from happenings and theatrical experiments around 1960: for example, Allan Kaprow’s Happenings (starting in 1959) were live events in which performers and sometimes the audience enacted unscripted scenarios in lofts or streets, breaking down barriers between art and life. Yayoi Kusama, Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneemann, and Chris Burden were among those who pushed performance’s boundaries in the 1960s–70s, using the artist’s body and risky actions as media. Schneemann’s 1964 Meat Joy or Burden’s 1971 Shoot (in which he was voluntarily shot in the arm) exemplified Performance Art’s shocking immediacy and its “active role for the spectator”. What made performance radical was its insistence that art could consist of transient actions, not lasting objects; a direct affront to the commercial art system. It invited audience participation and often addressed social or personal themes (from feminist body politics to trauma) in ways traditional painting could not. By making the process and presence the artwork, performance artists essentially “turned art viewing into an inclusive experience,” a trend that has only grown since the 1990s with participatory and socially engaged art.

Parallel to performance’s rise was the advent of Video Art, pioneered by artists who saw the newly affordable video camera as an artistic tool. Nam June Paik, often called the father of video art, famously used a Sony Portapak camera to film Pope Paul VI’s 1965 visit to New York and played the tapes the same day; an event often cited as the birth of video art. By the late 1960s, artists like Paik, Wolf Vostell, Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, and Bruce Nauman were exploring the possibilities of video technology as a medium, incorporating real-time recordings, TV screens, and closed-circuit feeds into their works. Video art could be screened, installed, or manipulated live, and it differed from cinema by often lacking narrative or actors. Early video pieces were frequently extensions of performance or conceptual art; for instance, Acconci’s Centers (1971) simply shows him pointing at the camera for 20 minutes, creating an unsettling confrontation with the viewer. Video art’s rebellious significance lay in its embrace of mass-media tools to make art, subverting television’s conventions and democratizing media production. It also resisted commodification: videotapes could be copied or broadcast freely, further undermining the uniqueness of the art object. From the 1960s onward (and especially with the explosion of digital video later), video and performance became accepted forms in museums, heralding a “redefinition of artistic expression” beyond painting and sculpture. Together, Performance and Video Art reflected a profound renewal of art’s purpose, bringing it closer to lived experience, technology, and social critique, and expanding the definition of what art can be.

During the 1970s and 1980s, many American artists turned their rebellious energy toward interrogating the structures of the art world itself and recycling existing images to expose cultural myths. This broad trend can be seen in two intertwined practices; Institutional Critique and Appropriation Art.

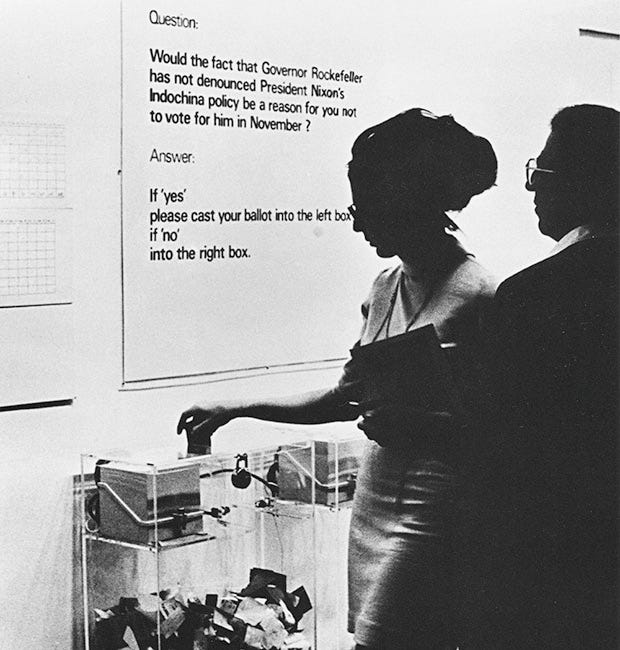

Institutional Critique emerged from late-1960s conceptual art and took explicit aim at museums, galleries, and the art market. Artists like Hans Haacke, Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Fred Wilson, and Andrea Fraser created works that revealed the hidden politics and biases of art institutions. For example, Haacke’s controversial 1971 survey piece (MoMA Poll) asked museum visitors whether a political figure’s reelection was desirable, directly confronting the museum’s supposed neutrality. As a movement (active especially in the 1970s–80s), Institutional Critique “makes the unacknowledged mechanics of art world funding, curation and acquisition explicit”. These artists questioned; Who decides what art is shown? What power dynamics or corporate interests lurk behind cultural institutions? Their works often consisted of research, documentation, or subversive tweaks to exhibitions that forced viewers to consider the economic and social frameworks of art. In doing so, they aimed to change those institutions or at least illuminate their “controversies, problems and blind spots”. This was a rebellion from within; many institutional critique artworks were, ironically, presented in the galleries they were critiquing; truly “biting the hand that feeds”, as some critics noted. Yet this practice ultimately renewed critical dialogue in art, making transparency and self-reflection part of contemporary art’s ethos. By the 1990s, a second wave of institutional critique merged with activism, targeting issues like toxic philanthropy or the lack of diversity on museum boards; causes that remain pressing in the art world today.

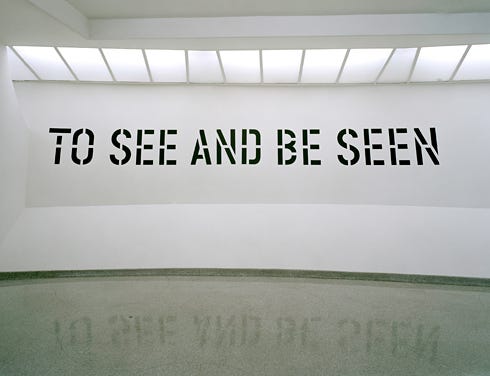

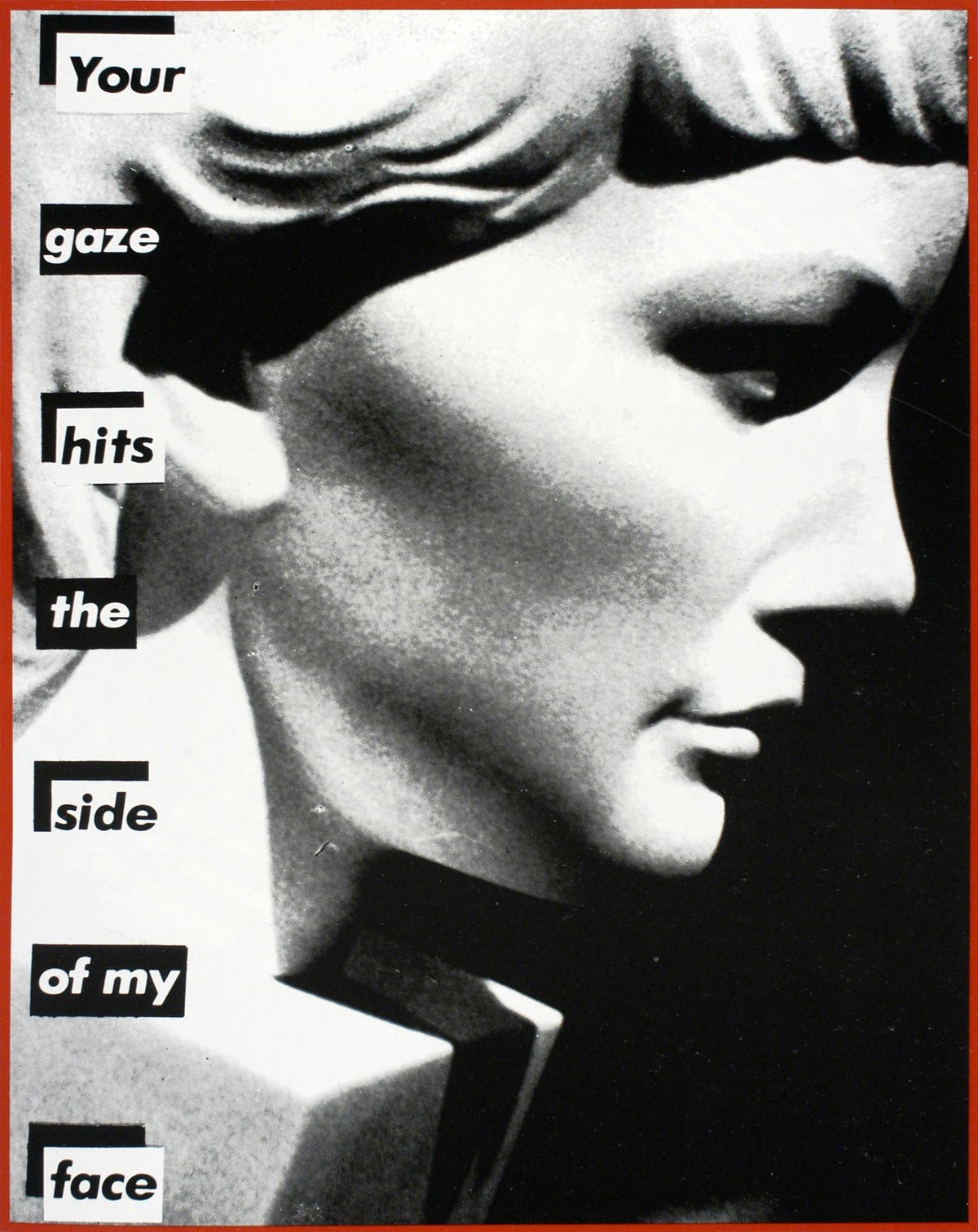

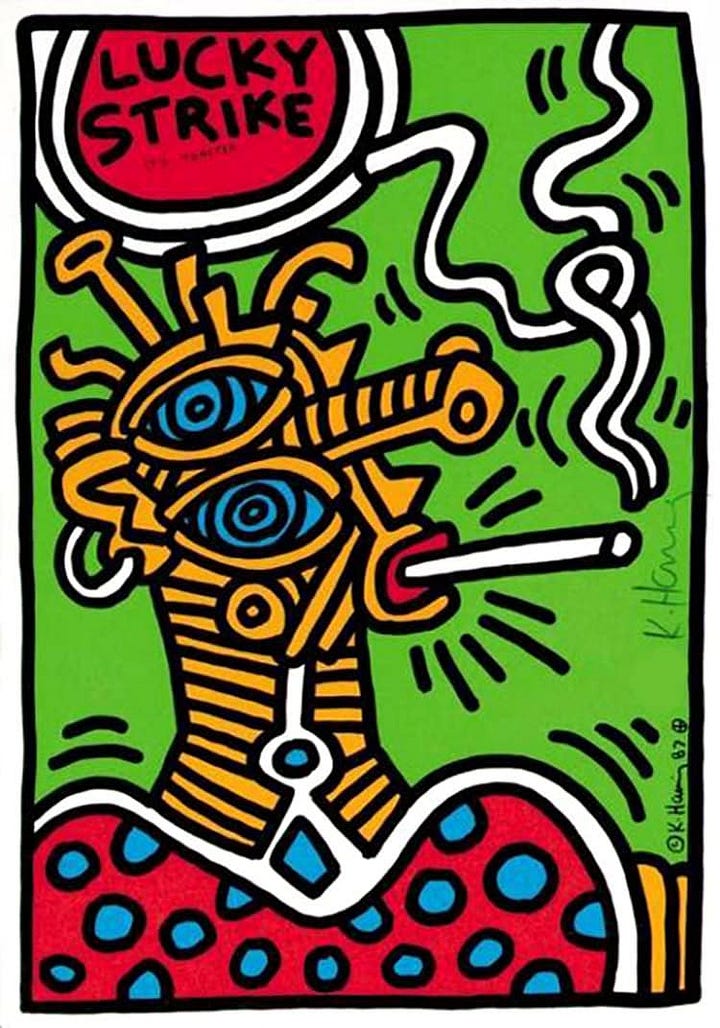

At the same time, a wave of artists in the late 1970s and 1980s developed Appropriation Art as a strategy to critique originality and mass media. Appropriation in art means deliberately borrowing or copying existing images, from advertising, art history, or popular culture, with minimal transformation, in order to make new works. This method was itself not new (Duchamp had appropriated a urinal as Fountain in 1917), but it became a hallmark of 1980s postmodernism. Sherrie Levine famously re-photographed Depression-era images by Walker Evans in 1981, presenting them as her art to question authorship and the aura of the original. Barbara Kruger lifted marketing photos and added bold text (“Your gaze hits the side of my face”) to lay bare the messages embedded in media images. As one analysis succinctly states: “Appropriation art debunks modernist notions of artistic genius and originality”, instead being “both critical and complicit” in subverting the meanings of its source material. This ambivalence was deliberate: by reproducing the very images that saturate society (fashion models, Hollywood icons, corporate logos, etc.), appropriation artists exposed how those images shape identity and desire. The so-called Pictures Generation, figures like Levine, Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, and Robert Longo, used appropriation to critique consumer culture, gender roles, and art itself. For example, Sherman’s staged self-portraits mimicked film stills to examine female stereotypes, while Prince’s re-photographs of Marlboro cigarette ads (removing the text to leave the cowboy image) highlighted the artifice of advertising and were themselves sold for high prices, blurring commerce and commentary. By the 1990s, appropriation had entered the mainstream of art, raising debates about copyright but firmly establishing that remixing imagery is a valid creative act. In sum, both Institutional Critique and Appropriation were postmodern rebellions: they rejected the modernist ideal of the solitary artistic genius and renewed art by treating context and content itself as raw material to be questioned. The result was art that made viewers more aware of the forces, institutions, media, history, that shape what we see and value as “art.”

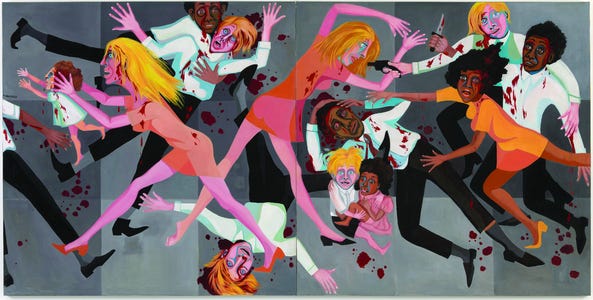

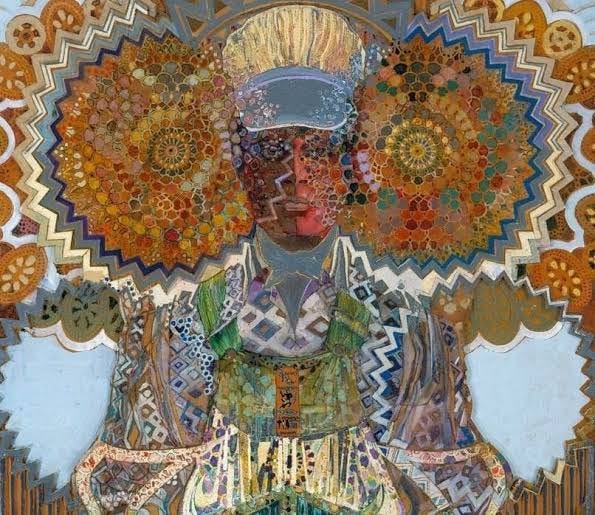

During the civil rights era of the 1960s and the rise of Black Power, African American artists launched what came to be called the Black Arts Movement (BAM), a cultural counterpart to the political movements for Black liberation. The Black Arts Movement was an African American-led art movement active roughly 1965–1975, dedicated to creating a new Black aesthetic and new cultural institutions. Through art and activism, BAM artists sought to uplift Black pride, celebrate African heritage, and directly address the Black experience in America. This was inherently a rebellion against both racial oppression in society and exclusionary practices in the art world. Prior to the 1960s, Black artists had often been marginalized or expected to conform to mainstream (white) styles. The Black Arts Movement rejected that tokenism. As writer Larry Neal famously declared, BAM was the “aesthetic and spiritual sister of Black Power”, applying Black nationalist and Pan-African ideas to art. In practice, this meant art by, for, and about Black people; art that spoke directly to Black communities and asserted new standards of beauty and relevance. Visual artists associated with BAM (many overlapping with the broader community of Black writers and musicians) included figures like Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar, Jeff Donaldson, Emma Amos, and members of collectives such as AfriCOBRA in Chicago. Their work often depicted Black heroes (historical or contemporary), used African motifs, or engaged with political topics like urban poverty and resistance. For instance, Ringgold’s 1967 American People Series paintings portrayed racial conflicts in bold, expressive style, while Saar’s 1972 assemblage The Liberation of Aunt Jemima transformed a mammy figurine into a Black power warrior, both works exemplify how BAM artists reclaimed images of Black identity. Importantly, BAM also founded new Black-run art spaces, theaters, and publications to nurture Black creativity outside white institutions. This infrastructural “nation within a nation” included community galleries, the Black Arts Repertory Theatre (founded by poet Amiri Baraka in 1965), and journals like Black Dialogue. Such institutions ensured that Black artists had platforms to present work on their own terms, which was itself a lasting legacy. In short, the Black Arts Movement represented a powerful renewal of American art through the lens of Black consciousness; making art more inclusive, politically engaged, and reflective of America’s diversity. Though the formal movement waned by the late 1970s, its influence endured in later generations of African American artists and in the increased visibility of Black art in museums.

By the early 1970s, the second-wave feminist movement had inspired a profound upheaval in the art world: women artists began organizing, creating work about female experience, and demanding equal recognition. The Feminist Art Movement (sometimes simply called the Women’s Art Movement) emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s with the conviction that art history and the contemporary art scene had overwhelmingly ignored or marginalized women. Feminist artists set out to change this by rewriting a male-dominated art history, challenging the existing art canon, and creating opportunities for women’s voices. This was both a rebellion and a renewal; a rebellion against sexist exclusion and a renewal of culture through inclusion and re-examination. Notably, feminist art was not defined by a single style but by an approach: it deliberately centered women’s perspectives and often addressed issues like the body, domestic labor, sexuality, and identity. As artist Suzanne Lacy said, the goal was to “influence cultural attitudes and transform stereotypes” through art.

One landmark of feminist art was Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974–79), a monumental installation honoring 39 historical and mythical women with elaborately symbolic place settings on a triangular table. This collaborative work, incorporating traditionally “feminine” crafts like needlework and ceramics, directly challenged the art establishment’s dismissal of such media and literally gave women a seat at the table of history. Feminist artists often embraced alternative materials and collaborative methods, consciously rejecting the macho “paint-slinging” myth of the solitary male genius. They turned to textile arts, performance, video, and body art, media with less entrenched male traditions, as vehicles to express female experience. For example, Miriam Schapiro incorporated quilting and fabric in her collages (coining the term “femmage”), elevating craft to high art. Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke used performance and the naked female body to reclaim female sexuality from the male gaze, as in Schneemann’s taboo-breaking performance Interior Scroll (1975) where she read from a scroll extracted from her body. Ana Mendieta created earth-and-body works addressing themes of violence against women and spiritual connection to the earth. These works demanded viewers to consider art from women’s intimate, sometimes taboo perspectives; an unprecedented shift.

Feminist artists also fought structural sexism by forming their own organizations and agit-prop groups. In 1972, Chicago and Schapiro started the Feminist Art Program in California, and that same year a pioneering women’s cooperative gallery, A.I.R. Gallery, opened in New York to showcase women artists. Perhaps the most famously rebellious were the Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous collective of women artists formed in 1985 who donned gorilla masks and used witty posters to call out sexism and racism in museum exhibitions (e.g., their poster stating “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”). By such actions, feminist art activism directly confronted the “boys’ club” of the art world.

The impact of the Feminist Art Movement was transformative. It opened museums and markets to women artists, recovered the forgotten contributions of women in art history, and infused contemporary art with new content about gender, personal narrative, and social justice. In effect, it expanded art’s definition to include half of humanity’s experiences. The movement also laid groundwork for later explorations of identity (intersecting with race, sexuality, etc.), as feminist art increasingly became intersectional from the 1990s onward. In sum, the feminist art movement of the 1970s–80s was both a necessary rebellion against an unjust system and a joyous renewal, unleashing a wealth of creativity that continues to shape art up to the present.

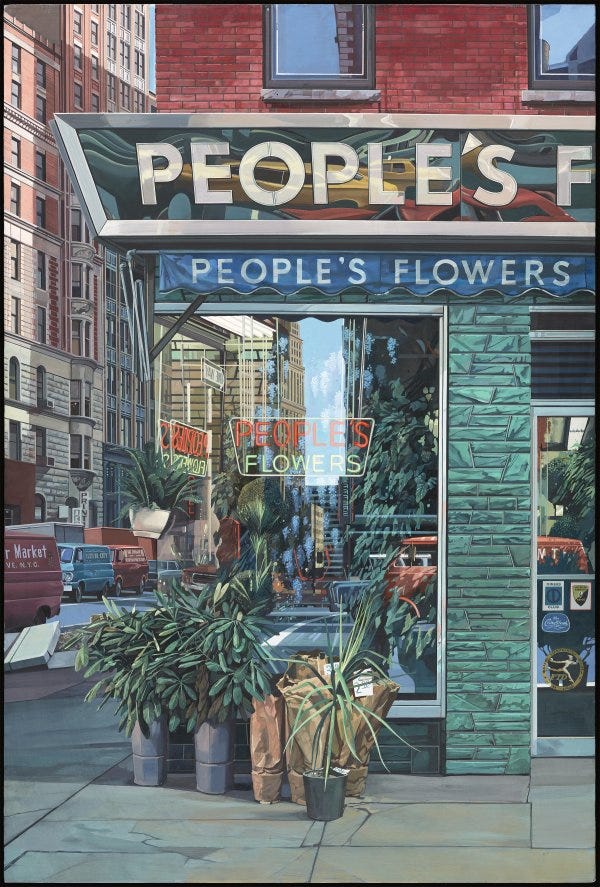

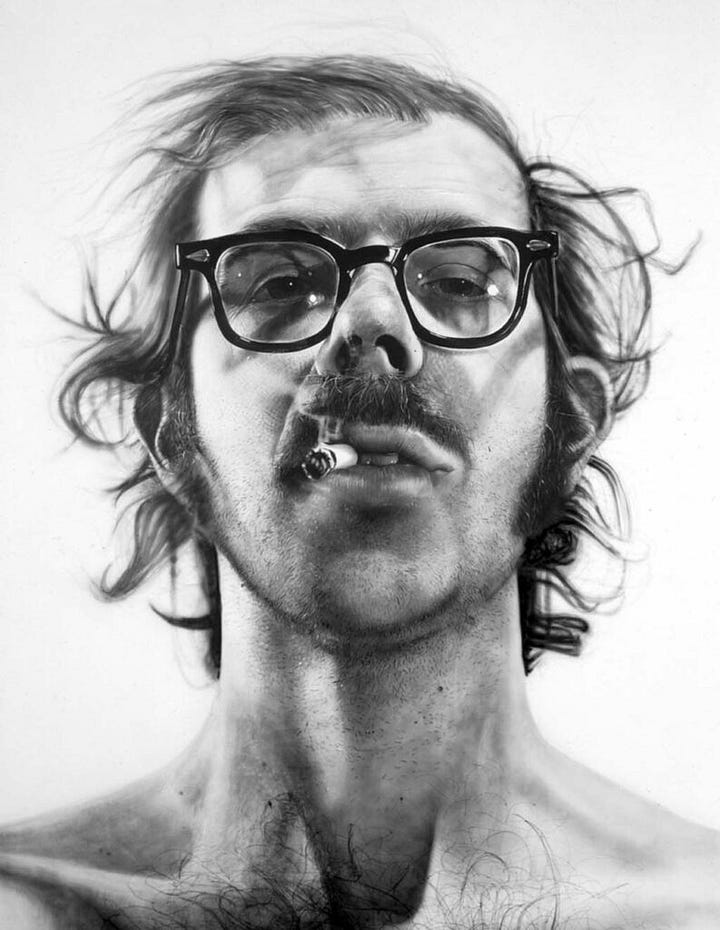

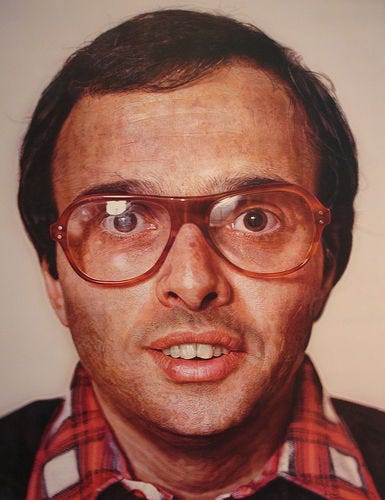

At the height of late-1960s abstraction and conceptualism, a group of American painters turned to an unlikely source for inspiration: the photograph. Photorealism (or Hyperrealism) was a movement in which artists used photographs as the basis to paint highly realistic, almost uncanny images that often looked more like large color photos than paintings. The movement began in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the U.S., evolving out of Pop Art and as a countercurrent to dominant abstract styles. In a sense, Photorealism represented a renewal of representational painting in an era that had largely forsaken it; yet it did so in a distinctly contemporary, even rebellious way. Rather than returning to academic realism or romantic subjects, Photorealists depicted the prosaic scenes of modern life (city streets, diners, motorcycles, suburban houses) with the impersonal sharpness of a camera. Richard Estes painted the reflective storefronts and neon of New York; Chuck Close made monumental, pore-by-pore portraits based on mug-shot-like photos; Audrey Flack produced vibrant still lifes loaded with glossy surfaces and Pop-cultural references. These artists would project or meticulously grid out a photograph and then reproduce the image as precisely as possible in paint; every gleam of chrome, every blur or grain of the source photo rendered by hand. The results were technically dazzling and often had a deadpan, documentary quality.

Critics initially bristled at Photorealism, questioning whether copying a photo was a legitimate artistic act. But Photorealists argued that by embracing the camera and photographic vision, they were simply acknowledging the reality of seeing in the 20th century. Indeed, the rise of mass photography and media was central to Photorealism’s purpose: one analysis notes that Pop Art and Photorealism both reacted to the “ever-increasing abundance of photographic media” in mid-century life. While Pop artists parodied commercial imagery, Photorealists “were trying to reclaim and exalt the value of an image” in the face of image overload. In this way, Photorealism can be seen as both rebellion and revival; a rebellion against the nonrepresentational orthodoxy of modern art (it was sometimes dismissed as retrograde by critics), but also a revival of intense craftsmanship and observation. Yet it was a decidedly modern kind of realism: filtered through photos, often devoid of overt emotion or narrative, and keenly attuned to the look of contemporary environments. Photorealism’s legacy has been significant. It presaged later hyperrealist art and foreshadowed postmodern discussions about simulation and reality. By the 1970s it proved, contentiously, that painting could still innovate by looking backward to reality, or at least to the mediated reality of the camera lens. In doing so, Photorealism reaffirmed the power of imagery at a time when many thought the idea had eclipsed the image in art.

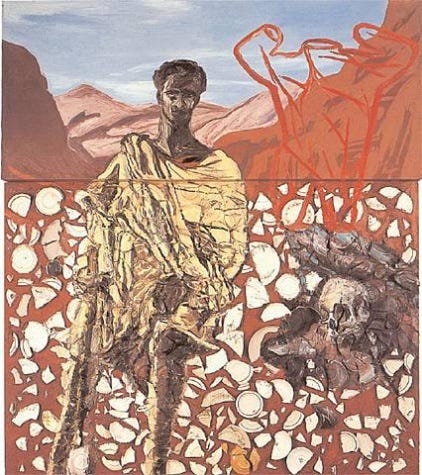

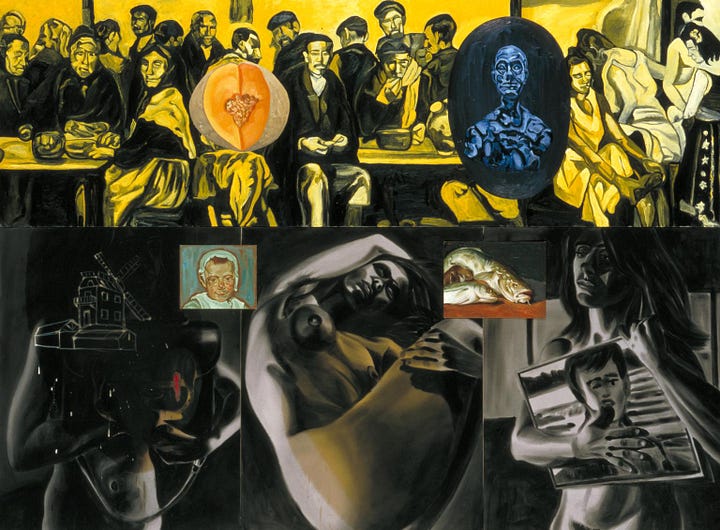

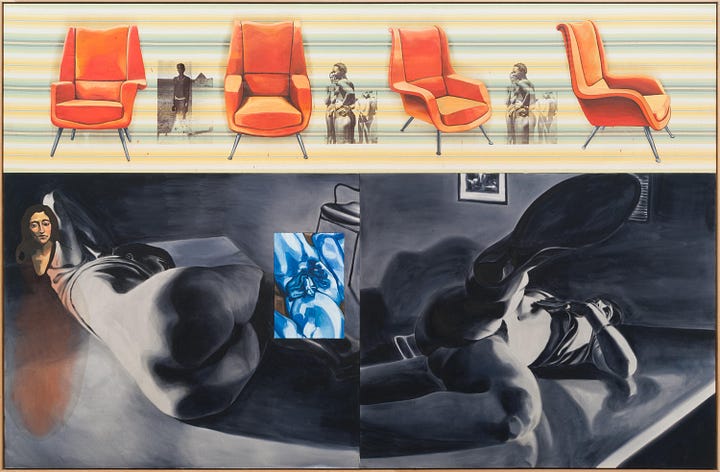

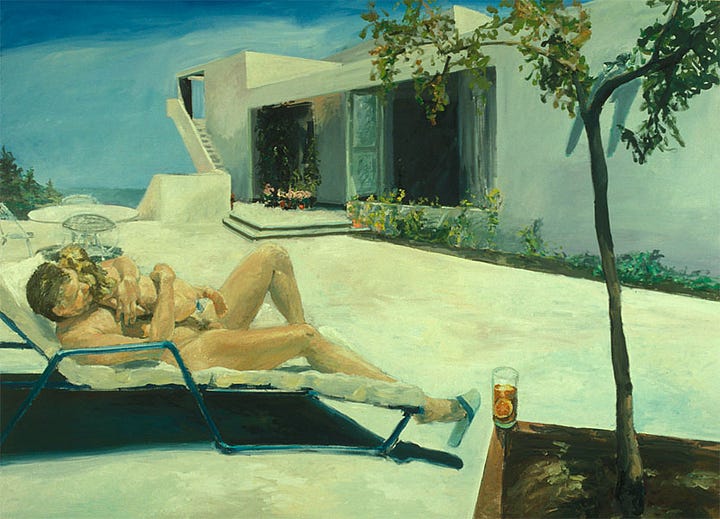

After a decade dominated by minimal, conceptual, and Pop art, the late 1970s and 1980s witnessed a dramatic return to expressive, narrative painting on a global scale. Labeled Neo-Expressionism, this movement saw artists re-embrace vigorous brushwork, intense color, and personal symbolism, in a manner reminiscent of early 20th-century Expressionists, yet with a postmodern twist. Neo-Expressionism “developed as a reaction against conceptual art and minimal art of the 1970s”, with painters returning to recognizable objects (often the human figure) portrayed in a rough, emotionally charged way. The movement emerged first in Europe (notably among the “Neue Wilden” or “New Fauves” in West Germany like Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Markus Lüpertz) and soon had parallel currents in the United States and elsewhere. In the U.S., prominent Neo-Expressionists included Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Eric Fischl, and Jean-Michel Basquiat (though Basquiat’s raw, graffiti-inflected style defies easy categorization). Their works were often large-scale, brashly painted canvases teeming with fragmented figures, mythic or pop-culture references, and a palpable sense of angst or absurdity. This new painting style was a rebellion against the cerebral detachment of the previous era; critics like Robert Hughes saw it as a resurgence of passion in art, while others lambasted it as a regression or a capitulation to the booming art market of the ‘80s. Indeed, Neo-Expressionism dominated the art market until the mid-1980s, with a frenzy of collectors driving up prices for these flamboyant paintings. The movement was not without controversy: it was criticized for marginalizing women (few female painters were initially included) and for basking in a kind of macho “bad boy” persona. Nonetheless, from an art historical perspective, Neo-Expressionism renewed interest in narrative and the visceral possibilities of paint after a period of cool, systematic art.

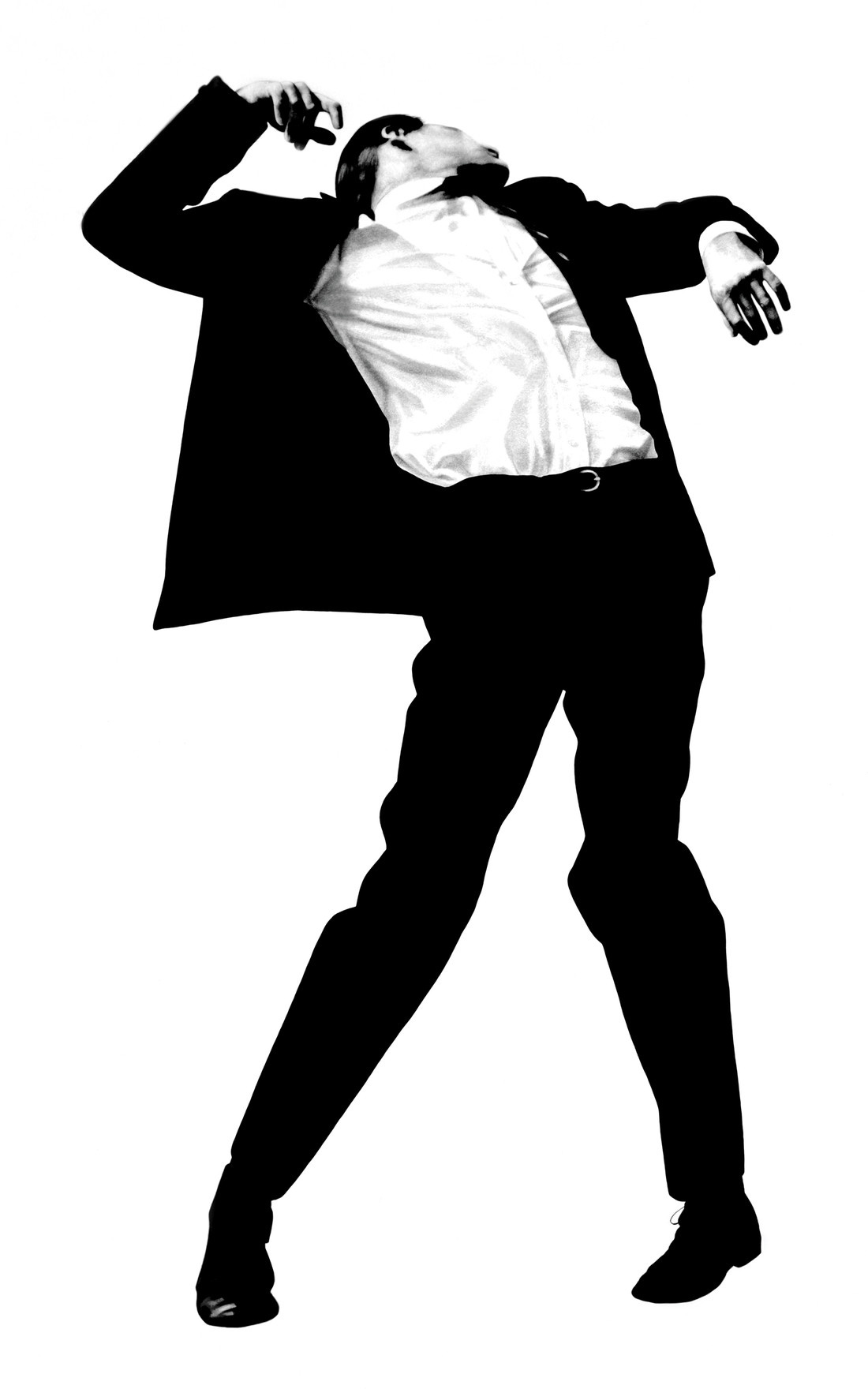

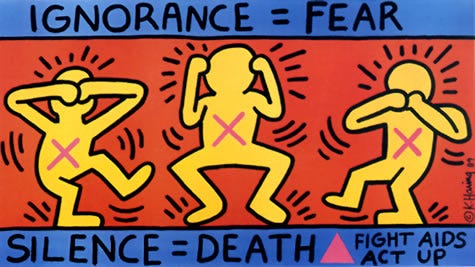

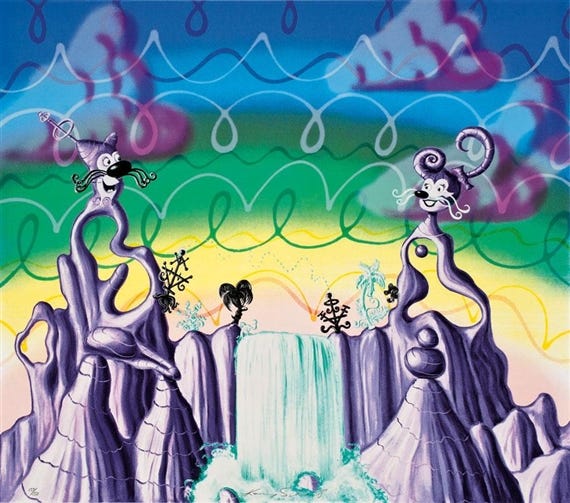

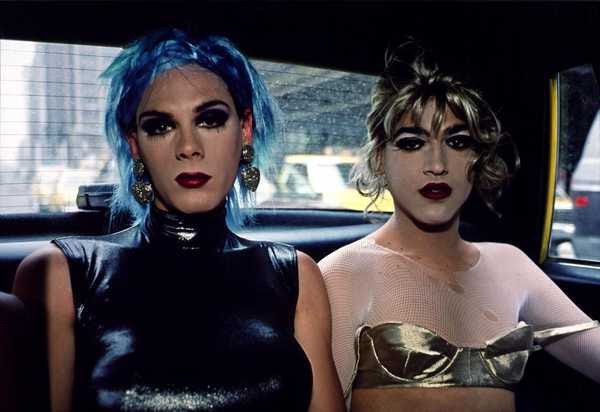

In New York, the East Village art scene of the early-to-mid 1980s became the breeding ground for many of America’s Neo-Expressionist and otherwise unconventional young artists. Amid the derelict, culturally vibrant East Village neighborhood, a cluster of artist-run galleries (such as Fun Gallery, Gracie Mansion Gallery, and ABC No Rio) sprang up starting around 1981, showcasing work that was edgy, unorthodox, and often infused with street culture. The East Village scene was a true artist community of “misfits and rebels”, where graffiti writers, punk musicians, and art school graduates collided. It nurtured now-legendary figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat, who rose from street graffiti poet to international art star; Keith Haring, who moved from chalk drawings in the subway to vibrant murals and gallery shows; Kenny Scharf, known for his day-glo comic-surreal canvases; and Nan Goldin, whose raw photographic chronicles of bohemian life defined an era. These artists often drew from graffiti, hip-hop, pop culture, and DIY aesthetics, gleefully disregarding distinctions between “high” and “low” art. The East Village scene’s do-it-yourself ethos and embrace of marginalized voices (LGBTQ artists, artists of color, etc.) made it a hotbed of experimentation. Wild, expressionistic painting was one prominent mode, for instance, Basquiat’s paintings mashed up crudely drawn figures, jazz and comic book references, and scrawled text, embodying a kind of neo-expressionist street energy. Haring’s bold graphic figures, originally drawn illicitly on subway station walls, became emblematic of 1980s New York art’s democratic spirit. In essence, the East Village was less a stylistic movement than an attitude of rebellion and community. As participant Marc Miller recalled, “young artists, misfits and rebels came together to create art in their own way”, borrowing from graffiti and collage and “provid[ing] the original context” for some of late 20th-century’s biggest names. By the late ’80s, the East Village art scene had largely dispersed; many artists were snapped up by mainstream galleries, and a 1987 market crash shuttered most local galleries. But its legacy was huge: it injected art with downtown subculture and helped launch movements like Street Art into the broader art discourse.

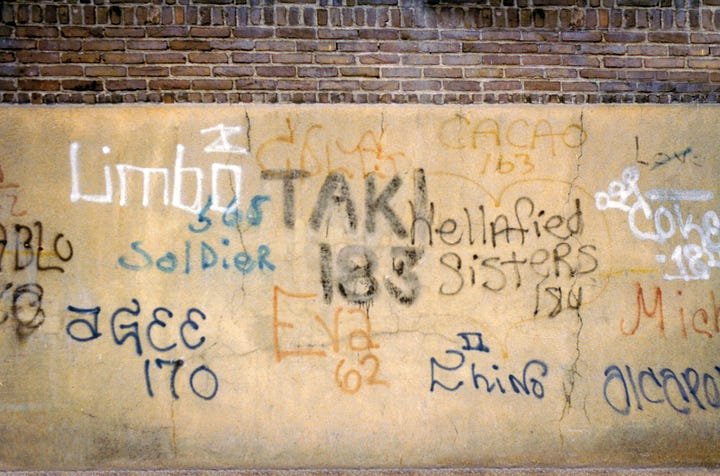

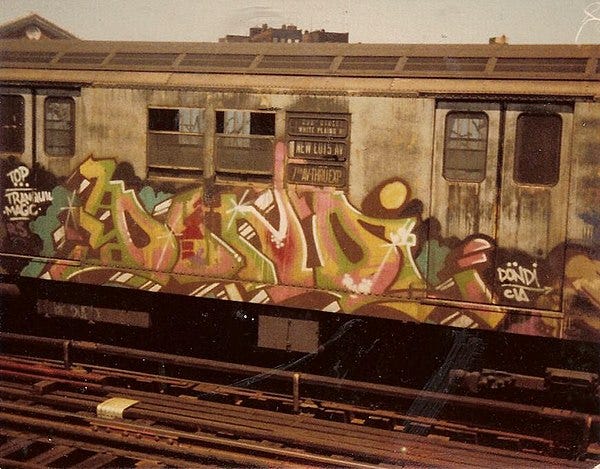

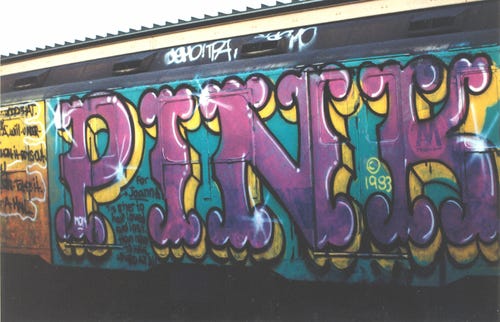

Born in the marginal, often illegal practices of urban youth, Graffiti Art (and later, Street Art) evolved from a subcultural expression in the 1970s into a global art phenomenon by the 2000s. Graffiti, in its classic form, refers to spray-painted names and designs on public surfaces; notably the stylized “tagging” and murals that proliferated on New York City subway cars and buildings in the early 1970s. Young artists from disadvantaged neighborhoods (many of them Black or Latino youths) created an entire visual culture on the city’s walls and trains, adopting nicknames like Taki 183, Dondi, and Lady Pink and competing to “get up” (have their work seen) all city. At first considered mere vandalism, graffiti gained artistic credibility over time as its complexity and creativity became evident. By the early 1980s, New York’s “Wild Style” graffiti, with its interlocking letters, bright fills, and cartoon imagery, had attracted the attention of downtown art patronage. Pioneering gallery shows (such as the 1980 Times Square Show and exhibitions at Fashion Moda and Fun Gallery) brought graffiti writers into dialogue with the formal art world. Moreover, some graffiti writers themselves, like Jean-Michel Basquiat (who began by tagging “SAMO” on Soho walls) and Keith Haring (who drew chalk murals in subway stations), successfully transitioned to gallery careers without losing their street sensibility. By incorporating graffiti into galleries, the art establishment started treating it “seriously” from the 1980s onward.

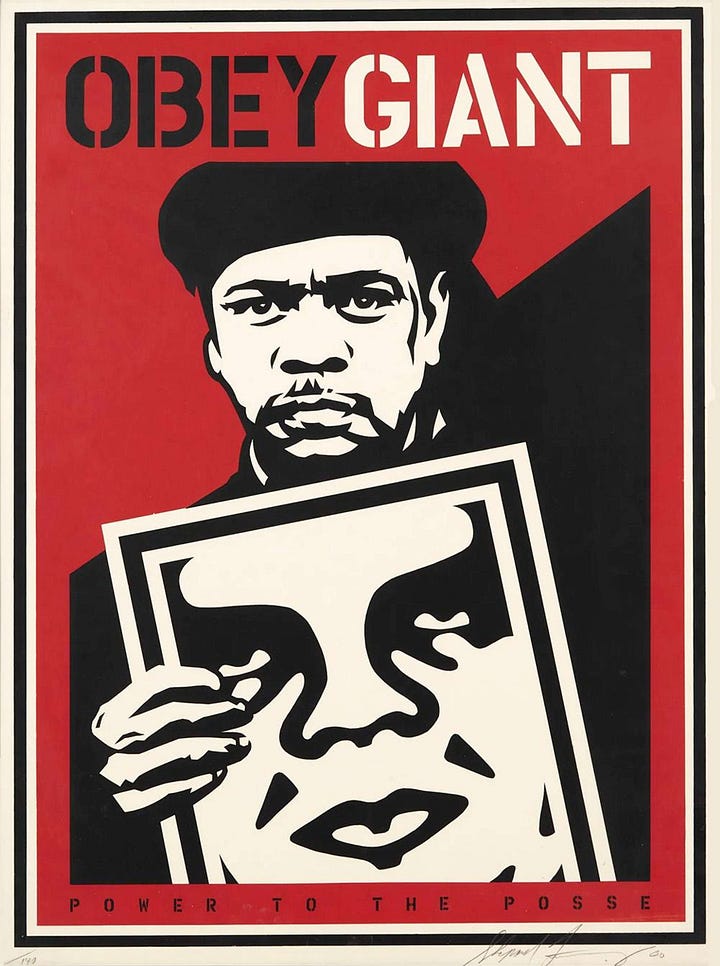

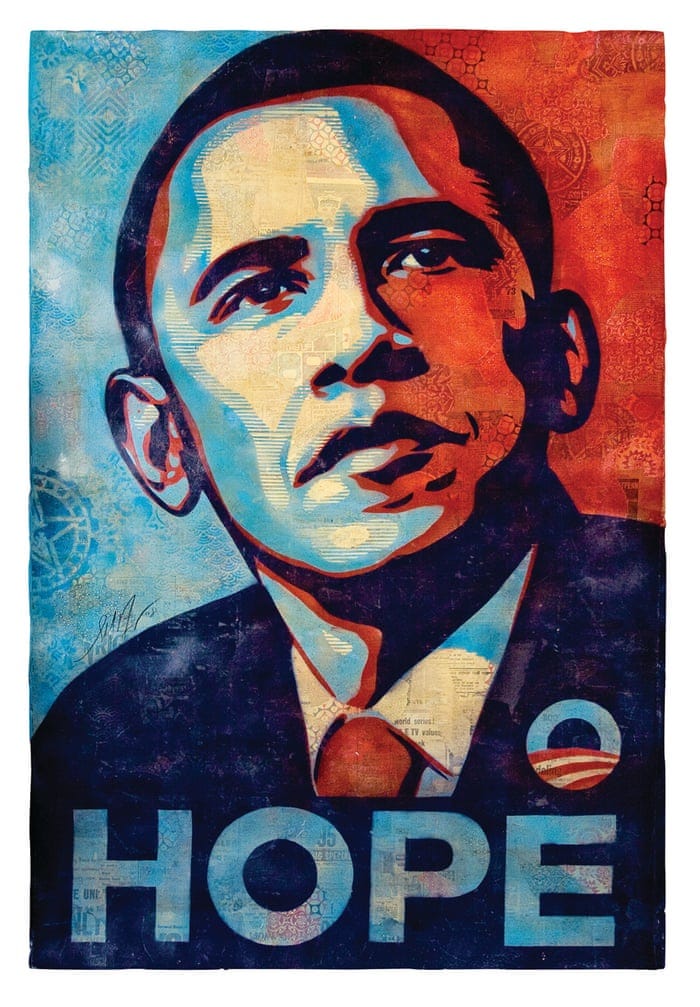

Street Art is a broader term that emerged in the 1990s and 2000s, encompassing not only graffiti-style writing but also stencil art, wheatpasted posters, sticker art, and urban installations; essentially, any unsanctioned art in public spaces. Street artists often convey overt social or political messages, blending bold visuals with subversive wit. International figures like Banksy (UK), Shepard Fairey (US), and Invader (France) became famous for their guerrilla art campaigns that reached massive audiences outside traditional venues. In the U.S., Street Art continued the lineage of ’70s graffiti while expanding its techniques: for instance, Shepard Fairey’s ubiquitous OBEY posters and later the Barack Obama HOPE image (2008) showed how street graphics could permeate mainstream culture. By the 2000s, cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Philadelphia had thriving mural and street art scenes, and major museums were beginning to showcase street-born artists.

The trajectory of Graffiti/Street Art is one of rebellion turned renewal. In its early days, tagging was a literal rebellion against the urban environment; a way for disempowered youth to assert presence (“I was here”) in a city that ignored them. It was often done in defiance of law (New York authorities fought a “war on graffiti” in the ’80s) and societal norms of property, which underscores its anti-establishment roots. Yet as it evolved, graffiti demonstrated remarkable artistry and fueled a renewal of visual culture with its fresh typography, characters, and energy. Graffiti crews brought an almost jazz-like innovation to lettering and spray-paint technique. When some of these artists moved to canvas or sculpture, they carried that energy into fine art, injecting new life into an art world some saw as stagnant. Importantly, graffiti and street art also democratized art; the city itself became a gallery, accessible to all, with murals addressing community concerns or adding beauty to neglected spaces. In recent decades, city governments that once scrubbed graffiti now commission street artists to create sanctioned murals; meanwhile, works by graffiti legends have fetched high prices at auction, marking a full ironic cycle from street to elite. Still, many street artists remain committed to activism – using murals to protest injustice or to celebrate local heritage.

To summarize, Graffiti/Street Art’s journey from subway tunnels to MoMA’s walls exemplifies the blend of rebellion and renewal: it began as outsider art rejecting the rules of both art and society, and it ended up expanding the very definition of art to include spray paint, stickers, and public intervention. As one historical account notes, by the 1980s even museums started treating graffiti as art, and artists like Basquiat and Haring proved that “graffiti art had become real art” worthy of critical and commercial attention. Today, street art is a global language, one that continually rejuvenates urban visual culture and keeps art in dialogue with the public sphere in a vibrant, if still sometimes controversial, way.

The advent of personal computers, digital imaging, and the internet in the late 20th century opened vast new frontiers for artistic creation. New Media Art is an umbrella term for the many forms of art that use emerging technologies, and from the 1990s onward, it has grown into one of the most dynamic areas of contemporary art. In general, “new media art refers to all forms of contemporary art made, altered, or transmitted using new forms of media technology”, including digital art, video and computer animation, virtual reality, Internet-based art, interactive installations, 3D printing, and even biotechnology art. This represents a profound renewal of art’s tools and experiences: artists are no longer limited to paint, stone, or film, but can create in cyberspace, manipulate genetic code, or build robotic sculptures.

The 1990s saw an explosion of such work, coinciding with the spread of the World Wide Web. Suddenly, artists could use the internet as both a medium and a distribution platform, reaching global audiences instantly. Early Net Art collectives (like JODI or äda’web) made web pages as art, filled with code glitches or playful interfaces that challenged how we experience the online world. Digital imaging allowed artists like Lynn Hershman Leeson or Cao Fei to create video works and avatars exploring identity in virtual realms. Interactive installations became popular; works that respond to viewer input or environmental data, exemplified by pieces like Camille Utterback’s motion-tracking projections or Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s large-scale public light installations controlled by participants. The rise of gaming and simulation inspired art as well: for instance, Cory Arcangel hacked Nintendo games to produce minimalist digital animations, and virtual reality experiences became artworks themselves, immersing viewers in artificial worlds.

What unites New Media Art is an ethos of experimentation with technology and a critical engagement with digital culture. Many new media artworks are interactive, inviting the viewer to be a participant or “user,” thus breaking the passive viewing mode of traditional art. They often comment on how technology is reshaping society, from surveillance and AI to social media and virtual relationships. For example, Nam June Paik’s 1995 installation Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii (a monumental map of America outlined in neon and filled with hundreds of flashing TV screens) presciently symbolized the connectivity and information overload of the digital age. Such works illustrate how new media artists both use technology as a tool and critique its impact, embodying the double-edged nature of our electronic era.

From a rebellious standpoint, Digital/New Media Art challenges long-held notions of art’s materiality and uniqueness. A digital file can be copied infinitely; interactive art shifts authorship partly to the audience; internet art bypasses galleries entirely by existing in the open online. In these ways, it subverts the traditional art market and forces institutions to adapt (e.g., how to collect a website or a piece of code-based art?). At the same time, it represents a renewal by embracing the zeitgeist: as the world becomes ever-more digital, artists ensure art remains at the cutting edge of human experience. By the 2020s, new media art has further expanded into realms like AI-generated art, blockchain and NFTs, and augmented reality, continuing the trajectory begun in the 1990s. It stands as a testament to art’s ability to reinvent itself through each technological wave, often critically, often playfully, but always in conversation with the future.

In the late 20th century, many artists began to question whether one even needed a fixed studio or permanent art objects to make meaningful art. The term “post-studio art” refers to practices that decenter the traditional studio creation of discrete art objects, favoring instead site-specific works, social processes, and ephemeral experiences. While the roots of post-studio thinking go back to the 1960s (think of Happenings, Fluxus events, and Conceptual Art that existed as ideas or actions), it wasn’t until the 1990s that such approaches gained broad acceptance under labels like participatory art, social practice, or relational aesthetics. Essentially, Post-Studio Art is art that can happen anywhere and often involves collaboration or community, rather than solitary studio labor. For example, Rirkrit Tiravanija became known in the 1990s for cooking meals for gallery visitors; an art of hospitality and social interaction that left no object, only the memory of shared time. Thomas Hirschhorn created temporary “monuments” in urban housing projects, built with local residents out of everyday materials, sparking neighborhood dialogue. These works embody a shift where the process and engagement are the art, not a final collectible product.

Simultaneously, the notion of Process Art, focusing on the act of making and the transformation of materials, has seen a resurgence in contemporary art. In the late 1960s, Process Art was associated with anti-form and ephemeral materials (e.g., Richard Serra’s splashed lead, Eva Hesse’s latex sculptures). In the present context, process-oriented art has expanded to include any art where change, duration, or the viewer’s participation is central. For instance, Andy Goldsworthy creates natural installations that are intentionally left to erode, so the process of nature reclaiming them is part of the piece. Olafur Eliasson often involves natural phenomena in real time (melting ice, drifting fog) as art, emphasizing flux.

What unites these trends is a rebellion against art as static commodity and a renewed emphasis on art as an activity or experience. “Participatory art in the western world has its roots in the 1960s… [but] it wasn’t until the 1990s that this form was broadly accepted as participatory or socially engaged art,” art historian Claire Bishop notes. By the 1990s and 2000s, museums and biennials began highlighting works where viewers might help build the artwork, attend a workshop, or be part of a performance; blurring the line between artist and audience. This reflects the influence of an increasingly networked, interactive society. One could say post-studio/process artists see art not as a precious object but as a catalyst, for community, conversation, or reflection.

Importantly, this approach often carries a political or utopian charge. If the 1960s gave us “happenings” as radical play, the contemporary era gave us social practice art aiming to address social issues. Artists like Suzanne Lacy orchestrate participatory events around topics like violence or poverty (for example, Lacy’s 1993 The Roof Is on Fire involved teens discussing stereotypes atop parked cars). The art is measured in impact and interaction rather than aesthetic finish. Such work can frustrate traditionalists, but it undeniably extends art’s scope. It also necessitates new ways for institutions to support and evaluate art, sometimes involving documentation, residencies, or collaborations with civic entities. In all, Post-Studio and Process Art represent a continued rebellion against art-as-commodity and a revival of art’s role as lived experience. They ensure that contemporary art remains dynamic and processual, much like life itself, rather than confined to static displays. This ongoing trend speaks to a broader impulse in 21st-century art: to connect with audiences in real time, outside elite spaces, and to trust that the journey of making or engaging can be as meaningful as any finished artwork.

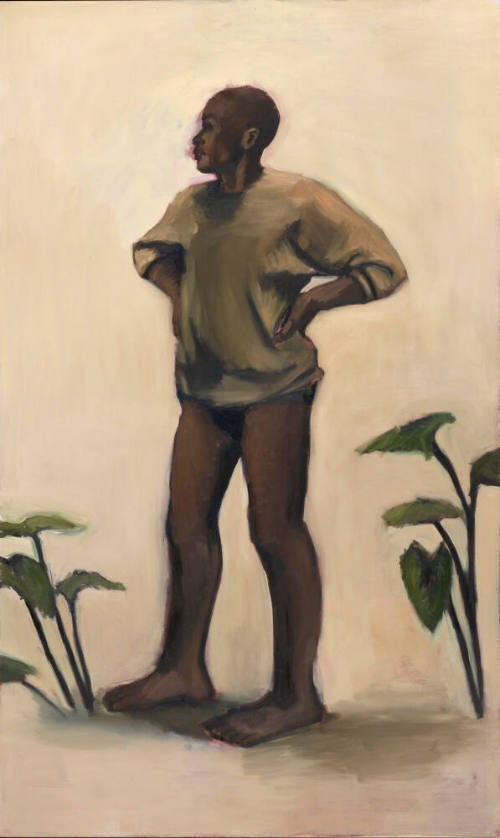

In the opening decades of the 21st century, painting, particularly figurative painting, made a notable comeback on the international art stage after a period when it was overshadowed by conceptual and media-based art. This resurgence of figurative painting in the 2000s–2010s can be viewed as a renewal of interest in storytelling, imagery, and the human figure, blended often with contemporary sensibilities. Observers noted that “since the early 2000s, figurative painting has gradually returned to the front of the scene, after years of dominance by conceptual and abstract art”. This revival was initially driven by established painters like Alex Katz (known for his cool, pared-down portraits since the ’60s) and George Condo (who paints grotesque yet classically-influenced figures) serving as godfathers to a new generation. By the mid-2000s, a wave of younger artists began engaging with figuration in fresh ways and achieving significant critical and commercial success.

Several factors underpinned this trend. One was a broader postmodern pluralism: by the 2000s, the art world had shed the dogma that painting was “dead,” embracing a “anything goes” mentality that allowed painters to reclaim the figure without irony. Additionally, a rising interest in identity, narrative, and historical reckoning; partly stemming from feminist, queer, and post-colonial discourses; found natural expression in figurative imagery. Artists sought to depict bodies and stories that had been marginalized, from the experiences of people of color to queer bodies to personal autobiography. For example, Kerry James Marshall, though active since the ’90s, gained wide recognition in the 2000s for his large paintings portraying Black figures in everyday and art-historical scenarios, explicitly correcting the absence of Black subjects in Western painting. Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley brought Black portraiture to new heights (famously painting official portraits of Michelle and Barack Obama in 2018), blending realism with stylization to assert Black presence and style. Elizabeth Peyton and John Currin, two New York painters who rose to prominence in the late ’90s, continued to paint figures in the 2000s; Peyton with intimate, wistful portraits of pop culture figures and friends, Currin with controversial, mannerist depictions often riffing on sexual themes, showing that figuration could be intimate, subcultural, or provocative.

Meanwhile, the market warmly embraced figurative painting, perhaps in part because collectors understood and coveted the traditional appeal of painting with a “twist.” Auction data from 2000–2015 showed a boom in sales of figurative works by artists like Peter Doig (whose dreamlike scenes evoke Gauguin and Munch), John Currin, George Condo, Alex Katz, and Elizabeth Peyton; five artists who together amassed roughly $399 million in sales over that period. This financial indicator underscores that the art world was not only intellectually but economically revaluing figurative painting. Moreover, a new generation of figurative painters emerged in the 2010s, often from diverse backgrounds and engaging boldly with identity and politics. Artists such as Njideka Akunyili Crosby (mixing Nigerian and American imagery in collaged domestic scenes), Toyin Ojih Odutola (exploring Black diasporic identity through rich portraiture), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (imagining elegant figures of African descent in timeless settings), Salman Toor (depicting queer Brown youth in tender, moody vignettes), and Dana Schutz (known for her expressive, sometimes grotesque figurations) gained prominence. These painters share a confidence in blending representation with personal or cultural narratives, often with vibrant palettes and stylistic references ranging from Old Masters to comic books. Their success reflects “common characteristics” of the new figurative scene: many are women or artists of color, and they infuse figurative painting with themes of gender, race, and sexuality that were once outside its mainstream.

In short, the resurgence of figurative painting in the 2000s–2010s stands as both a rebellion and a renewal. It rebelled against the late 20th-century critical bias that viewed painting (especially figurative painting) as exhausted or reactionary. These artists proved that depicting the figure could be as radical as any conceptual gesture when approached with fresh eyes and voices. And it renewed the centuries-old medium of painting by bringing in contemporary content and previously excluded perspectives. As a result, gallery walls in the 21st century are once again populated by faces, bodies, and stories; a reminder that even as art evolves through technology and abstraction, the human figure retains a perennial power to convey meaning. This cyclical return to figuration highlights art’s ongoing dialogue with its own history, continuously revitalized by new generations who make the old form speak in new tongues.

From the Pop artists who turned soup cans into icons, to the digital artists who conjure virtual worlds, American art since the 1950s has been defined by bold acts of rebellion and continual renewal. Each movement, whether embracing minimal form, the earth itself, feminist collaboration, street graffiti, or cyberspace, broke with convention to address the urgencies of its time. Together, these movements chart a course through an era of dizzying change, reflecting how artists responded to (and often anticipated) societal shifts; the consumer boom, identity politics, technological revolution, and beyond. Crucially, these movements did more than just reject previous art; they reinvented what art could be, expanding its subjects, methods, and participants. American art from Pop to the present thus reveals a dynamic ecosystem wherein rebellion against the old generates renewal in the new. This pattern continues today, as artists carry forward the legacy of innovation; ever ready to challenge norms and imagine fresh possibilities for art in contemporary life.

References:

Alloway, Lawrence. American Pop Art. Macmillan, 1974.

Broude, Norma, and Mary D. Garrard, editors. The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. Harry N. Abrams, 1994.

Cotter, Holland. Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott. The New York Times, 11 Sept. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/09/11/arts/design/robert-colescott-new-museum-review.html.

Crow, Thomas. The Rise of the Sixties: American and European Art in the Era of Dissent. Yale University Press, 1996.

Deutsche, Rosalyn. The Question of 'Public Art': Curating the City. October, vol. 70, 1994, pp. 35–54.

Doss, Erika. Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Finkelpearl, Tom. Dialogues in Public Art. MIT Press, 2000.

Heartney, Eleanor. Postmodernism. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Jones, Amelia. Body Art: Performing the Subject. University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

Kaprow, Allan. Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. Edited by Jeff Kelley, University of California Press, 2003.

Kwon, Miwon. One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. MIT Press, 2004.

Lucie-Smith, Edward. Race, Sex and Gender in Contemporary Art. Art Books International, 1994.

Molesworth, Helen, editor. Work Ethic. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003.

Nochlin, Linda. Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? ARTnews, Jan. 1971.

Owens, Craig. The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism. October, vol. 12, 1980, pp. 67–86.

Pindell, Howardena. The Heart of the Question: The Writings and Paintings of Howardena Pindell. Midmarch Arts Press, 1997.

Rose, Barbara. American Art Since 1900: A Critical History. Praeger Publishers, 1967.

Sandler, Irving. The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism. Harper & Row, 1970.

Stiles, Kristine, and Peter Selz, editors. Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings. University of California Press, 1996.

Taylor, Brandon. Avant-Garde and After: Rethinking Art Now. Harry N. Abrams, 1995.

Thompson, Nato. Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the 21st Century. Melville House, 2015.

Walker, Hamza. Basquiat and the Bayou. Ogden Museum of Southern Art, 2014.

Wollen, Peter. Raiding the Icebox: Reflections on Twentieth-Century Culture. Verso, 1993.

I love this piece. Honestly, I can and should do an essay on each of these movements as a jumping off point because it’s the last frontier of real art movements that moved the needle. Now we live in an excuse of art being made into a movement instead of the other way around.

There is a lot to think about here. In the way you have put these together as a flowing thought to contrast and flex against one another is perfect. Well curated writing, dear Rogue.

This was a thorough and enlightening recap of the fine art movements from the mid-twentieth century on; in other words, during my lifetime. I was especially interested in what is happening in the digital age. Thank you for this!