Edmonia Lewis was a pioneering sculptor of African American and Native American heritage who overcame tremendous racial and gender-based obstacles to achieve international acclaim. As the first professional Black and Indigenous woman sculptor to gain widespread recognition, she carved a path for future generations of artists while producing some of the most compelling neoclassical sculptures of the 19th century. Her work, which often drew on themes of identity, freedom, and resilience, continues to be studied and celebrated in art history.

Mary Edmonia Lewis was born on July 4, 1844, in Greenbush (now Rensselaer), New York, to a Black father and a Chippewa (Ojibwa) mother. Her mother was a skilled craftswoman, and her father worked as a gentleman’s servant. Orphaned at a young age, Lewis and her older brother, Samuel, were raised by their maternal aunts in the Ojibwa tradition near Niagara Falls. She spent her childhood immersed in their customs, learning beadwork and other traditional crafts that would later influence her artistic style (Buick 21).

Recognizing her potential, Samuel, who had become a successful entrepreneur in the gold rush, financed Edmonia’s education. In 1859, she enrolled at Oberlin College in Ohio, one of the few higher education institutions at the time that accepted women and students of color. Oberlin was a progressive school, yet Lewis still encountered racism and prejudice. In 1862, she was accused of poisoning two white classmates and was brutally beaten by a white mob before standing trial. Though acquitted, the incident, followed by another false accusation of theft, ultimately led to her expulsion before she could complete her degree (Romero 117).

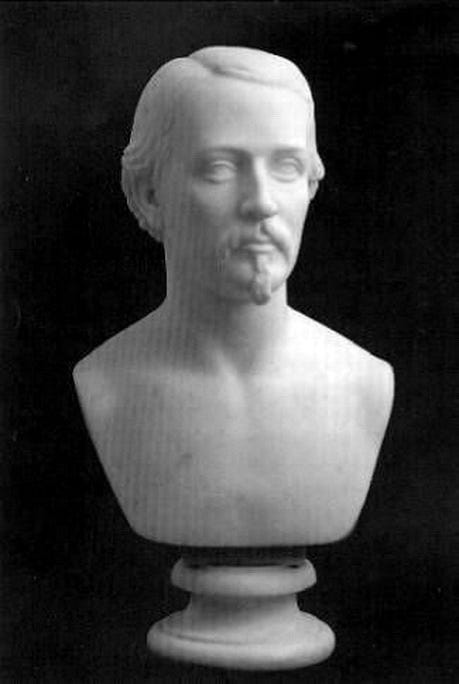

After leaving Oberlin, Lewis moved to Boston in 1863, determined to pursue a career in sculpture. She initially struggled to find formal training, as racial and gender barriers limited her access to established studios. However, she found a mentor in Edward A. Brackett, a prominent sculptor known for his abolitionist sympathies. Under his guidance, she honed her craft and began sculpting busts and medallion portraits of notable abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, and Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (Child 72).

Her bust of Colonel Shaw, the leader of the all-Black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, was particularly well received and became a commercial success. She sold numerous copies, using the proceeds to fund her move to Europe in 1865 (Holland 182).

In 1866, Lewis traveled to Rome, where she found a more supportive artistic environment compared to the racial prejudices she had experienced in the United States. Italy, and particularly Rome, was home to a thriving community of expatriate artists, including women sculptors such as Harriet Hosmer and Anne Whitney. These artists embraced the neoclassical tradition, a style that idealized the human form and often depicted historical, biblical, and mythological subjects.

Lewis established her own studio and quickly gained recognition for her ability to sculpt marble with remarkable skill, an unusual feat at the time, as most sculptors relied on assistants to execute their designs. She prided herself on working directly with the material, a testament to her technical prowess and commitment to artistic authenticity (Ferrari 41).

Her works from this period often explored themes of freedom, resilience, and cultural identity. One of her earliest major sculptures, Forever Free (1867), depicted an emancipated Black man and woman, symbolizing the triumph of abolition. Inspired by the passage of the 13th Amendment, the piece celebrated newly won freedom while maintaining a solemn dignity (Reynolds 138).

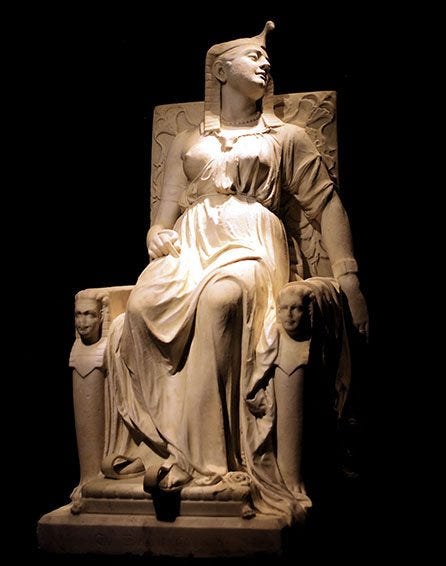

Edmonia Lewis’s most famous and ambitious work, The Death of Cleopatra (1876), was exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Unlike traditional portrayals of Cleopatra’s demise as a graceful and romanticized event, Lewis presented a strikingly realistic and dramatic version, capturing the moment after the Egyptian queen’s suicide. The life-sized sculpture defied Victorian sensibilities and shocked many viewers with its unflinching portrayal of death (Child 118).

After the exposition, The Death of Cleopatra was lost for decades, only to be rediscovered in a Chicago storage yard in the late 20th century. It is now housed in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where it remains one of Lewis’s most celebrated works (Holland 210).

Another important piece, Hagar (1875), depicted the biblical figure Hagar, a concubine cast out into the wilderness. Many scholars interpret the sculpture as an allegory for Lewis’s own struggles as a marginalized artist, navigating themes of displacement and survival (Romero 145).

Lewis also created works that reflected her Indigenous heritage, such as The Old Arrow Maker (1872), which depicted a Native American elder and his daughter. This sculpture reinforced her commitment to representing both aspects of her cultural identity (Buick 39).

Despite her international recognition, Lewis faced financial difficulties later in life. As neoclassicism declined in popularity and modernist movements took hold, patronage for her work diminished. By the early 1900s, she faded into obscurity. Her later years remain somewhat mysterious, but records indicate she moved to London, where she lived until her death on September 17, 1907 (Ferrari 57).

Edmonia Lewis’s groundbreaking career opened doors for artists of color and women in the field of sculpture. As the first African American and Native American sculptor to gain international acclaim, she navigated immense obstacles to establish herself in a field dominated by white men.

Today, her surviving works are housed in prestigious institutions, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Howard University Gallery of Art. Her sculptures continue to inspire contemporary artists and scholars, serving as powerful symbols of perseverance and artistic excellence.

In recent years, scholars and museums have worked to reintroduce Lewis’s contributions to a broader audience, acknowledging her role as a trailblazer in American art history. The renewed interest in her work underscores the significance of her achievements and the enduring relevance of her themes of identity, freedom, and resilience (Reynolds 165).

Edmonia Lewis’s story is one of triumph over adversity. Despite the racial and gender biases of the 19th century, she carved out a space for herself in the art world, leaving behind a body of work that continues to captivate and inspire. As art institutions and historians continue to recover and celebrate her legacy, Lewis’s sculptures stand as lasting testaments to her vision, talent, and determination.

References:

Buick, Kirsten P. Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject. Duke University Press, 2010.

Child, L. Maria. The Freedmen's Story. The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 23, no. 136, 1869, pp. 70-81.

Ferrari, Gabriele. Edmonia Lewis: Wildfire in Marble. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Holland, Juanita. African American Women Artists: A Historical Perspective. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2004.

Reynolds, C. J. Neoclassicism and Race: The Work of Edmonia Lewis. University of California Press, 2015.

Romero, Patricia. Profiles in Perseverance: Women of Color in the Arts. Routledge, 2002.

I think that’s probably the most impressive thing — her immense body of work. This woman must have had a chisel in hand ALL THE TIME! Between traveling and opening her own studio she truly was a woman far ahead of her period. Few had the ability to overcome race and gender in such a fluid way. It must truly have been because her talent was so extraordinary ❤️🔥

Love, love, love Ms. Lewis' work...and pioneering ways. Such a classic in so many ways!