From Happenings to Bio Art: The Body as Medium in Avant-Garde Practice

This content explores body and performance art involving physical endurance, pain, nudity, self-harm, trauma, and political violence, with graphic depictions that may be disturbing or triggering.

The following explores themes of body art and performance art, including content that addresses physical endurance, pain, nudity, self-inflicted harm, psychological trauma, and political violence. Some works discussed involve graphic depictions of bodily manipulation, ritualistic acts, and controversial performances that may be disturbing or emotionally triggering to some readers. Please proceed with care, and prioritize your well-being while engaging with this material.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a wave of radical innovation swept through the art world, leading to the development of Body Art and Performance Art. These artistic movements redefined the traditional boundaries of art by focusing on the human body and live action as central media for artistic expression. Influenced by earlier artistic concepts such as Allan Kaprow’s Happenings and the dematerialization theories of Conceptual Art, Body Art and Performance Art challenged institutional norms, probed identity and politics, and explored the limits of artistic media. Notable artists like Yves Klein, Carolee Schneemann, Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys, Vito Acconci, and many others pushed the boundaries of art-making, integrating corporeal actions, ritual, endurance, and even self-harm into their practices. These movements not only redefined the role of the artist and their body within the work but also laid the groundwork for future developments in Video Art, Relational Aesthetics, Bio Art, and digital new media.

At its core, Body Art uses the human body as the primary medium of expression, often involving endurance, abjection, or self-inflicted pain to confront the viewer with the artist's physical presence. It emerged as a response to the dematerialization of the art object seen in late-1960s Conceptual Art, where the focus shifted from material objects to the ideas and processes behind their creation. Body Art, therefore, collapses the traditional boundaries between the artist and their work, highlighting vulnerability and corporeality as crucial elements of the artistic process (Britannica).

Performance Art, on the other hand, refers to a time-based live presentation where the actions of the artist (or participants) constitute the artwork itself. Unlike Body Art, Performance Art encompasses a wide range of artistic activities, including theatricality, sound, and audience interaction. While Body Art focuses on the physical body as a site of transformation or confrontation, Performance Art can include ritualistic gestures, political statements, and experimental actions that extend beyond the body itself (Britannica).

****GRAPHIC IMAGES****

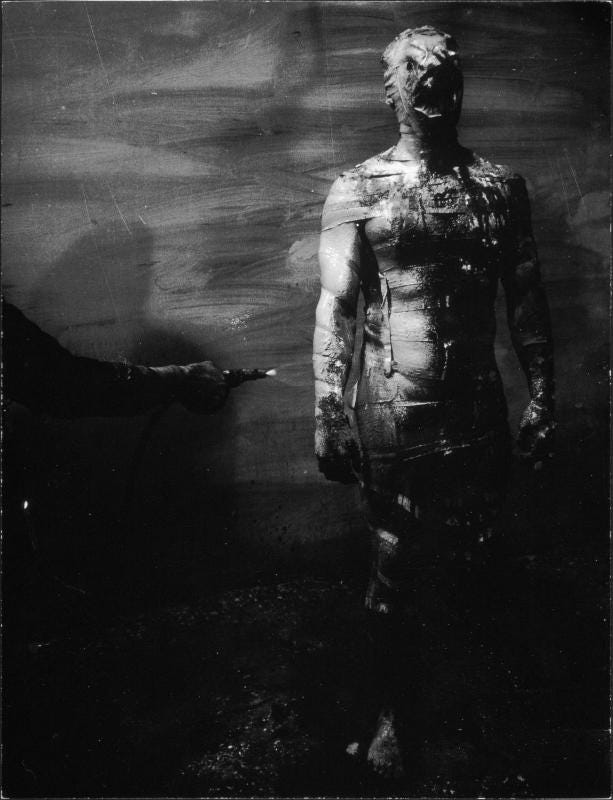

The roots of Body Art and Performance Art can be traced to earlier experimental practices such as Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings” in the late 1950s and early 1960s. These events broke down the traditional distinctions between art and life by inviting participation and occurring in non-traditional spaces, like streets or warehouses (Artsy). The Fluxus movement, with its embrace of chance, noise, and subversive play, further laid the groundwork for the development of body-centered art (Artsy). At the same time, Viennese Actionists like Hermann Nitsch and Otto Mühl engaged in extreme acts involving blood, violence, and body fluids to interrogate the boundaries between art, ritual, and human experience (Artsy).

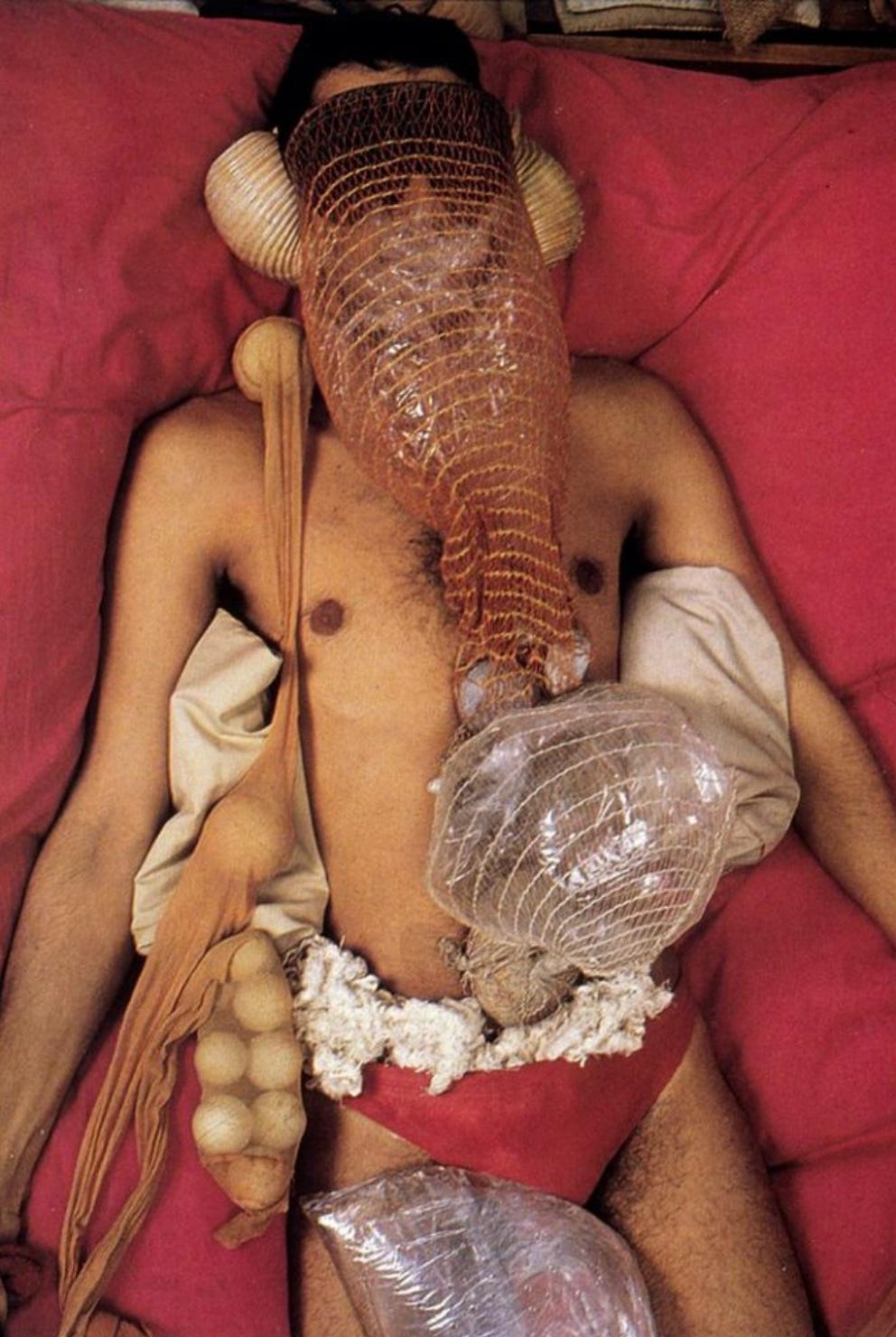

Neo-Concrete artists such as Lygia Clark in Brazil also integrated the body into their work in the late 1950s. Clark's participatory “relational objects” and sensorial exercises questioned the static nature of traditional sculpture and emphasized the interaction between the body and the art object (Tate). By the early 1960s, Yves Klein’s performances, such as his Anthropometries (1960), further eroded the traditional boundaries of painting by using the human body to create imprints on canvas, thus rejecting the primacy of the painted surface (Tate).

While Body Art and Performance Art share common ground in their rejection of traditional art objects and their focus on the artist’s body, they differ in emphasis. Body Art specifically centers on physical interventions with the body, often involving self-harm or endurance to highlight the artist’s corporeal presence. Performance Art, however, encompasses a broader range of live actions, including political performances, theatrical monologues, and participatory rituals, all of which may or may not involve the body in the same way (TheArtStory).

The contributions of individual artists to Body and Performance Art are numerous and varied, each adding unique dimensions to the movement. Yves Klein, for instance, used his Anthropometries (1960), in which models coated in his signature International Klein Blue paint pressed their bodies against canvas, to critique the male-dominated art world and explore the body as a medium of expression (Tate).

****GRAPHIC IMAGES****

Carolee Schneemann’s Meat Joy (1964) presented a visceral and erotic ritual involving raw fish, paint, and ecstatic performers, challenging conventional notions of sexuality and the body in art (MoMA). In her later work Interior Scroll (1975), Schneemann extracted a scroll from her body, confronting societal taboos around the female body and the objectification of women (Tate).

****GRAPHIC IMAGES****

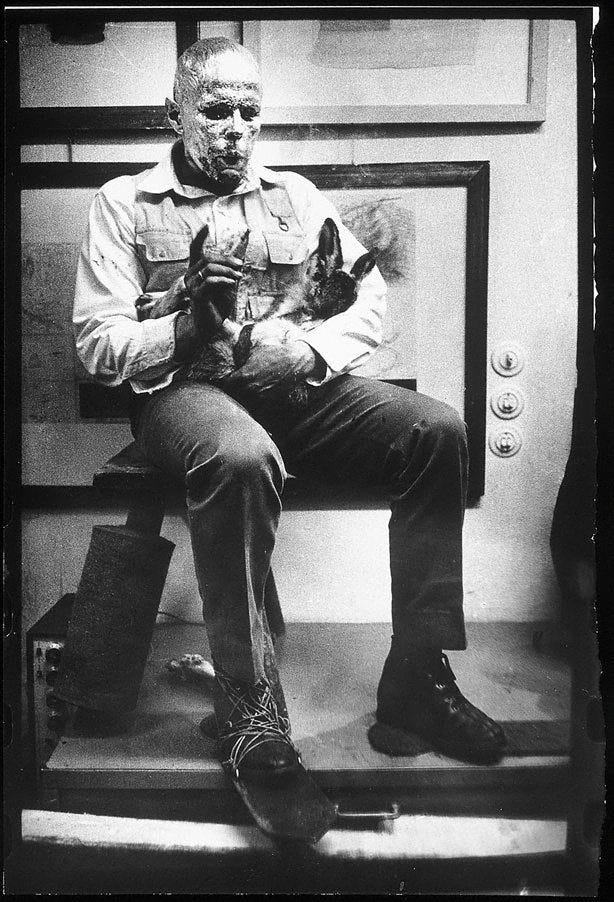

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964) invited the audience to cut pieces of her clothing as she sat silently, exploring vulnerability, the gaze, and the relationship between artist and viewer (MoMA). Joseph Beuys’s performances, such as How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965) and I Like America & America Likes Me (1974), explored themes of ritual, healing, and cultural exchange, while Vito Acconci’s Seedbed (1972) delved into voyeurism and power dynamics by positioning himself under a gallery ramp and vocalizing fantasies about visitors passing by (Tate).

****GRAPHIC IMAGES****

Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series (1973–80) used her body to create ephemeral earthworks, connecting identity, exile, and the natural world (MoMA). ORLAN’s controversial carnal art performances in the 1990s, which involved plastic surgeries as art, critiqued beauty standards and the medicalization of the body (TheArtStory). These artists, among many others, pushed the boundaries of art by involving the body as both subject and medium in the creation of meaning.

****GRAPHIC IMAGES****

Body Art and Performance Art also explored key theoretical themes related to the body, ritual, identity, and politics. The body as a medium allowed artists to collapse the distinction between artist and artwork, turning the human form into both subject and object (Britannica). Endurance and pain were central to many works, with artists like Gina Pane, whose Azione Sentimentale (1973) involved ritual self-cutting, testing the limits of physical and psychological endurance to evoke catharsis and confrontation (MoMA). Performance Art often intersected with identity politics, addressing issues of gender, race, and sexuality, as seen in the works of Schneemann, Ono, and Acconci.

****GRAPHIC IMAGES****

Performance Art also became a platform for political activism, as exemplified by Tania Bruguera’s performances on totalitarianism and immigration, and Joseph Beuys’s actions addressing the trauma of war (Britannica). These artists used the live, ephemeral nature of their works to interrogate contemporary social and political issues, embedding their personal narratives within the public sphere.

The legacy of Body Art and Performance Art is evident in the subsequent development of Video Art, Relational Aesthetics, and Bio Art. Video Art, particularly through its institutionalization in the 1980s at MoMA, embraced the principles of live action and interactivity, expanding the possibilities of performance into digital and networked realms (MoMA). Relational Aesthetics, as theorized by Nicolas Bourriaud, further developed the participatory nature of art, emphasizing social interaction as the core of the artistic experience (Wikipedia). Bio Art, as seen in works like Eduardo Kac’s GFP Bunny (2000), merged art with biotechnology, challenging ethical and environmental issues while continuing the tradition of body-centered artistic exploration (ekac.org).

Body Art and Performance Art revolutionized the art world by introducing the human body and live action as essential media for artistic expression. Through their explorations of identity, politics, and the body, these movements reshaped how art was understood, produced, and experienced. Their impact can still be seen in contemporary practices that blur the boundaries between artist and audience, physical and digital realms, and art and life.

Works Cited

Body and Performance Art – Western Painting. Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/art/Western-painting/Body-and-performance-art. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

Carolee Schneemann. Meat Joy. 1964. MoMA, www.moma.org/collection/works/126279. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

Cut Piece. MoMA, www.moma.org/audio/playlist/15/373. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

GFP Bunny. Eduardo Kac, www.ekac.org/gfpbunny.html. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare. Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/How_to_Explain_Pictures_to_a_Dead_Hare. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

I Like America & America Likes Me. Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Like_America_%26_America_Likes_Me. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

Kaprow, Allan. A Brief History of Happenings in 1960s New York. Artsy, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-what-were-1960s-happenings-and-why-do-they-matter. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

Lick and Lather. Janine Antoni, www.janineantoni.net/lick-and-lather. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica. Tate, www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern/display/lygia-clark-and-

helio-oiticica. Accessed 4 Feb. 2025.

😳

Cronenberg did a film very much in this vein recently; “Crimes of the Future” (2022)

I 🫡 give you top kudos for addressing this directly. I’m a bit squeamish so I do appreciate your top line warning.