Art has been a central part of human culture for millennia, serving as both a tool for personal expression and a means of communication. The question of how art creates meaning is complex, touching on various aspects of symbolism, context, technique, and personal experience. At its core, art generates meaning by engaging the viewer on a deep, often subconscious level, where visual elements, cultural references, and emotional responses combine to create a unique interpretive experience.

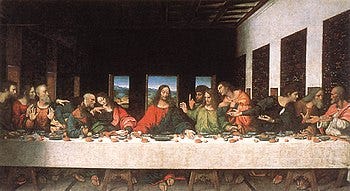

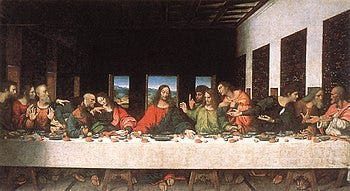

One of the most important ways art creates meaning is through symbolism. Artistic works are filled with symbols (objects, colors, figures) that represent broader themes or ideas. For example, in Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, the positioning of the figures, the use of light and shadow, and even the choice of materials all contribute to the theological and philosophical meaning of the piece. Jesus’s outstretched arms, symbolizing his impending sacrifice, and the different emotional responses of the apostles emphasize the themes of betrayal, faith, and redemption (Kemp, Leonardo da Vinci). Similarly, in literature and visual art, objects such as a dove (peace), a skull (mortality), or a snake (temptation) transcend their literal meanings to embody significant ideas about the human experience. Art's reliance on these symbols allows for rich, layered interpretations that extend beyond the specific moment of creation, connecting the artwork to broader cultural, historical, and spiritual contexts.

Another significant factor in how art creates meaning is the relationship between the artist's intention and the viewer's interpretation. Art is a form of communication that requires both the sender (the artist) and the receiver (the viewer) to actively engage. As noted by art historian Hans-Georg Gadamer, art cannot be understood simply through the artist's intention; rather, it exists as an event where meaning is generated in the act of viewing (Gadamer, Truth and Method). The meaning of a piece of art, then, is not fixed but evolves with each viewer's personal experiences, social context, and cultural background. This dynamic interaction between the artist and the viewer is evident in works such as Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, which was painted in response to the bombing of a Spanish town during the Spanish Civil War. While Picasso’s intention was to protest the violence, the piece’s fragmented forms, chaotic lines, and somber tones evoke a range of emotions in viewers, depending on their own perceptions and experiences with violence and war (Gombrich, The Story of Art).

In addition to symbolism and the artist-viewer dynamic, the formal elements of art—composition, color, texture, and technique—also contribute to the creation of meaning. These elements are not merely aesthetic; they actively shape how the viewer engages with the artwork. For instance, the use of contrasting colors in Caravaggio’s works, such as the dramatic interplay of light and dark in The Calling of St. Matthew, serves not only to create visual impact but also to symbolize the conflict between light and darkness, good and evil, within the human soul (Cole, Caravaggio: A Life). Similarly, the brushwork and texture in Van Gogh’s Starry Night evoke a sense of movement and emotional turbulence, amplifying the themes of isolation and existential longing that the painting conveys (Naifeh & Smith, Van Gogh: The Life). These formal choices invite the viewer to engage with the emotional and conceptual depths of the work, guiding them toward a deeper understanding of its meaning.

The role of emotion in art is equally significant in how meaning is created. Emotion is both a central element of artistic creation and a powerful force in how art is experienced. Artists often use their work as a means to express personal emotions or comment on societal issues. This is particularly evident in the works of artists like Edvard Munch, whose painting The Scream is an exploration of existential fear and anxiety (Cohen, Art and Emotions). The swirling forms and vibrant colors in The Scream are not just visual elements—they are emotional expressions that resonate with viewers, evoking feelings of unease and vulnerability. The emotional content of art, therefore, plays a crucial role in its capacity to engage the viewer, providing a direct emotional experience that adds depth to the work's meaning.

Furthermore, art's ability to evoke emotion is not limited to its content or form; it is also shaped by the viewer’s own emotional state. As noted by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the emotional impact of art is often influenced by the viewer’s psychological and cultural background (Csikszentmihalyi & Robinson, The Art of Seeing). This explains why different individuals may experience the same work of art in radically different ways, depending on their personal histories, emotions, and experiences. This emotional response, therefore, is part of the meaning-making process. The viewer’s engagement with the emotional aspects of the artwork allows them to make personal connections to the work, and in doing so, they are actively involved in generating its meaning.

In sum, art creates meaning through a combination of symbolic representation, formal elements, the interaction between the artist and the viewer, and emotional engagement. These factors contribute to art’s power to communicate complex ideas, evoke deep emotions, and reflect the human condition. Art is not simply a static object to be observed; it is an active process that invites the viewer into a dynamic exchange, where meaning is created through personal experience and collective cultural understanding. By exploring how these elements work together, we gain insight into the profound role that art plays in shaping both individual and societal consciousness.

References:

Cohen, Jon. Art and Emotions. Harvard University Press, 2010.

Cole, Michael. Caravaggio: A Life. HarperCollins, 2005.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, and Robinson, Rick. The Art of Seeing: An Interpretation of Art in Terms of Human Experience. University of California Press, 1990.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Truth and Method. Continuum, 2004.

Gombrich, E. H. The Story of Art. Phaidon Press, 2006.

Kemp, Martin. Leonardo da Vinci. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Naifeh, Steven, and Smith, Gregory White. Van Gogh: The Life. Random House, 2011.