Cave paintings are prehistoric artworks created on the walls and ceilings of caves, representing a form of parietal art typically produced by early humans. In archaeological terms, these paintings are widely accepted as prehistoric in origin. The earliest known examples date back over 40,000 years to the Upper Paleolithic period and have been discovered across the globe. These images, primarily featuring animals, hand stencils, and geometric shapes, mark a profound milestone in human cognitive evolution and artistic expression. They offer a unique glimpse into the mental worlds of hunter-gatherer societies, illuminating their environments, belief systems, and creative impulses.

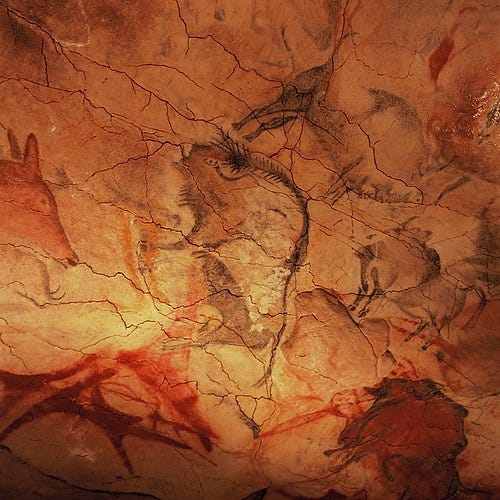

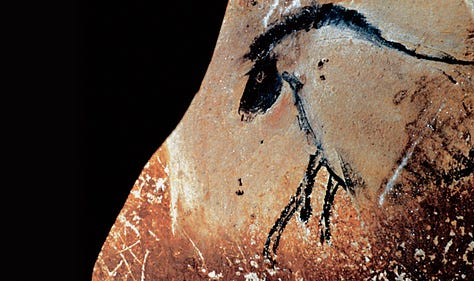

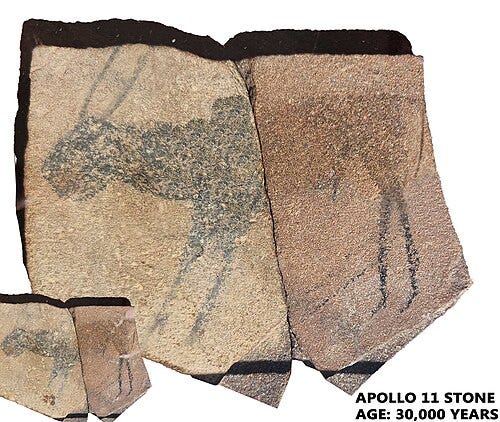

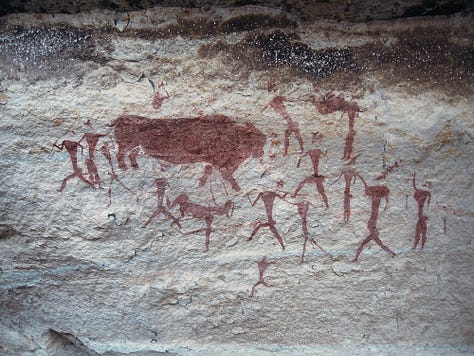

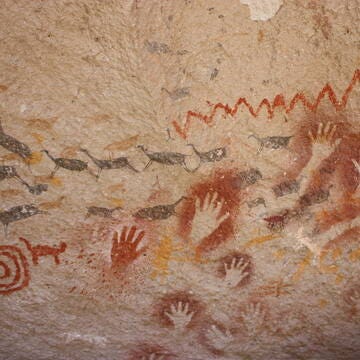

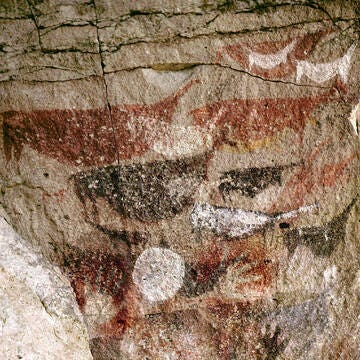

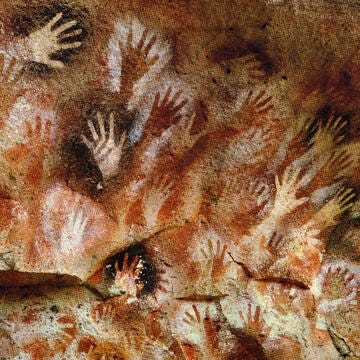

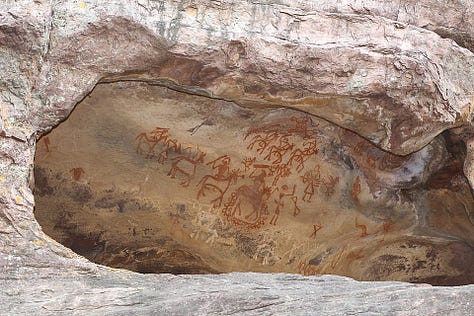

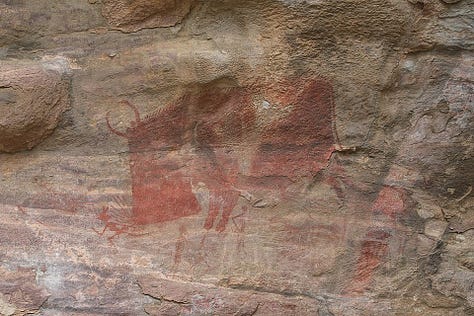

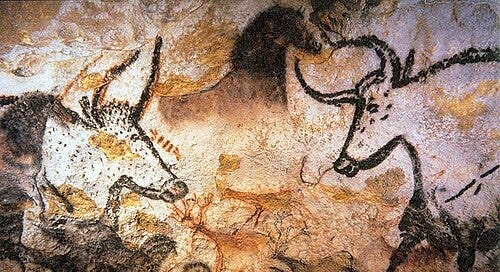

The phenomenon of cave art is truly global. In Europe, the Franco-Cantabrian region, encompassing areas of modern-day France and Spain, hosts hundreds of decorated caves. Among the most famous are Lascaux (France, approximately 17,000–22,000 years ago), Altamira (Spain, roughly 36,000 years ago), and Chauvet (France, circa 32,000–30,000 years ago). Additional decorated caves have been identified in regions like Italy and Britain, including Creswell Crags. In Asia, notable examples appear in Southeast Asia: Sulawesi’s painted caves in Indonesia date to around 40,000–44,000 years ago, while Borneo’s Lubang Jeriji Saleh boasts figurative scenes estimated at 51,000 years old. South Asia's Bhimbetka rock shelters in India span from the Paleolithic era into historical periods, with early examples (~10,000 BCE) depicting animals and hunting scenes. Africa also features a rich tradition of rock art, from the Apollo 11 Stones in Namibia (ca. 25,000 years ago) to South Africa’s Drakensberg paintings and Saharan masterpieces in Tassili n’Ajjer dating from the late Pleistocene to the Holocene. The Americas, too, hold important examples, such as Argentina’s Cueva de las Manos (c. 7000–3000 BCE), renowned for its thousands of stenciled handprints. Indeed, decorated caves and rock shelters have been discovered on every habitable continent, a phenomenon that highlights the global nature of early human symbolic behavior. Despite vast geographic distances, cave art around the world displays recurring motifs (animals, hands, and abstract symbols) that suggest a shared symbolic vocabulary among early hominins.

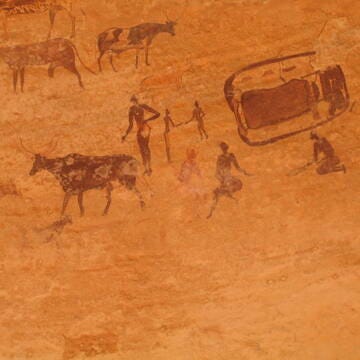

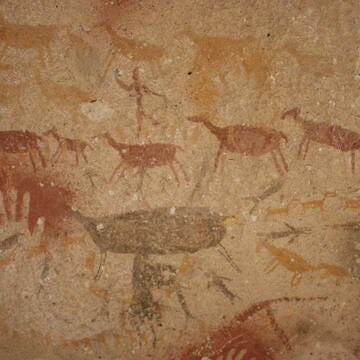

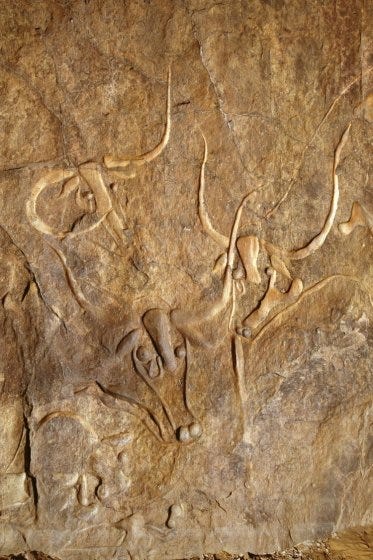

Each region offers unique contributions to this prehistoric legacy. Europe’s major sites like Lascaux, Chauvet, and Altamira are known for complex polychrome representations of animals such as bison, horses, and deer. In Asia, sites like Sulawesi and Borneo depict local fauna (including pigs and buffalo) alongside human and hybrid figures, sometimes in narrative form. Africa’s rock art emphasizes antelopes, elephants, and human hunting scenes; the Sahara’s depictions include domesticated cattle and early camels. The Americas provide vibrant examples such as hand stencils and guanaco figures from Argentina’s rock shelters. These case studies confirm that, regardless of region, early humans and hominin relatives expressed remarkably similar themes and styles in their rock art. This consistency across time and space underscores the universal role of cave painting in the prehistoric human experience.

The techniques and materials employed in creating cave paintings were both inventive and resourceful. Prehistoric artists relied on basic tools and naturally available materials. Pigments were typically derived from mineral and organic sources, such as red and yellow ochre (iron oxides), hematite, limonite, manganese dioxide (for black), charcoal or bone black, and occasionally lime for white. These materials were ground into powders and mixed with binders, ranging from water and animal fat to blood or plant juices, to ensure adherence to the rock surface. Brushes may have been crafted from twigs, moss, or animal hair, although many application methods required no brush at all.

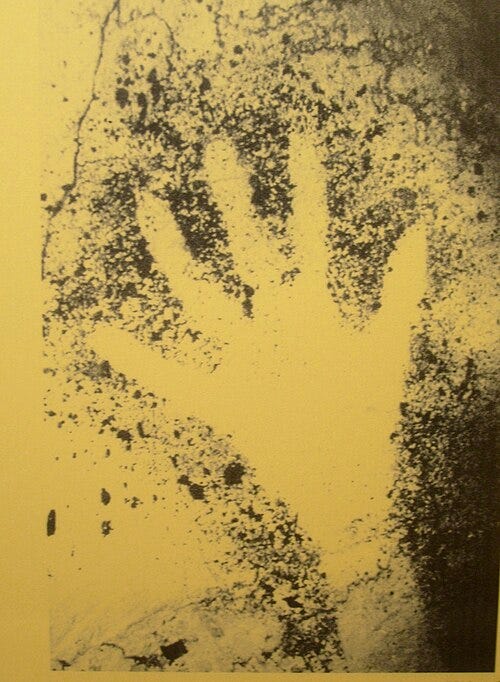

Artists used a wide array of techniques to apply pigment. Some employed fingerpainting or smearing, directly pressing or rubbing pigment onto the rock. Others utilized dabbing and stippling methods with pads or rudimentary brushes to create textured effects. One particularly innovative method involved spraying pigment through hollow bones or reeds, a technique often used to produce hand stencils by placing a hand against the wall and blowing pigment around it. Engraving was another common method, wherein flint or bone tools were used to scratch outlines into the stone before or after applying pigment. Highly skilled painters even manipulated the natural contours of the cave walls, using bumps and hollows to achieve three-dimensional effects that brought animal forms to life.

Scientific analyses of specific sites support these observations. At Lascaux, artists employed flint blades to carve contour lines and used ground ochre or charcoal for coloration. Pigments were often thinned with talc or water to create nuanced shading and chiaroscuro effects. At Altamira, studies revealed that charcoal and red ochre were combined and diluted to achieve tonal variation. Conservation reports have shown that prehistoric artists typically relied on a limited set of tools, perhaps only a few brushes or pads, and sometimes used stencils made from animal hide. Most outlines, however, were executed freehand, using fingers or porous applicators. In short, cave art reveals a basic but sophisticated “painter’s kit” composed of minerals, natural tools, and clever application methods, including the use of bone blowpipes, that together achieved astonishingly vivid and enduring results.

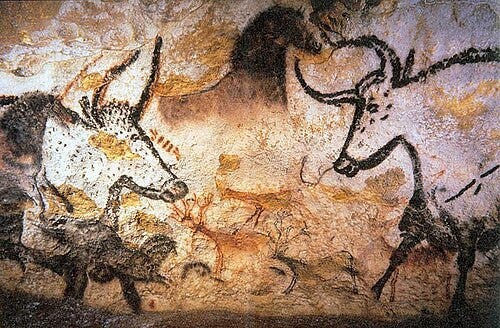

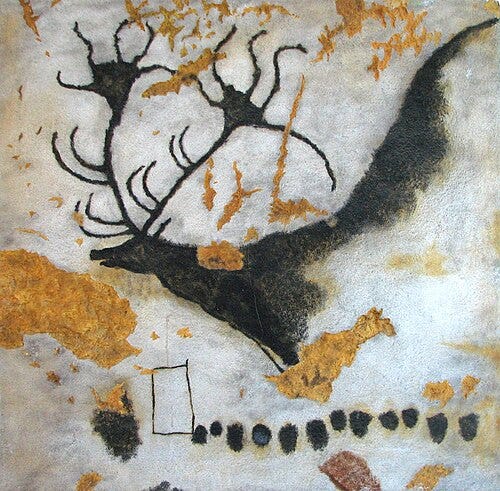

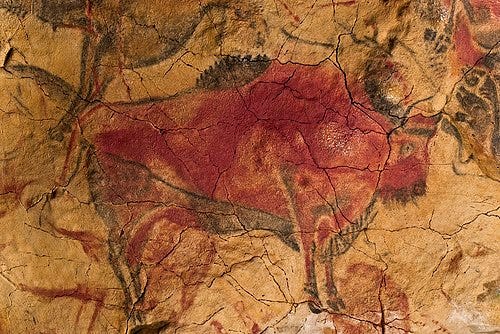

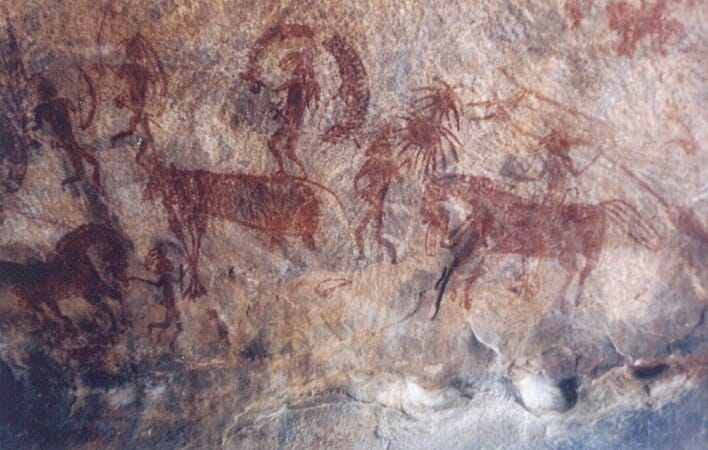

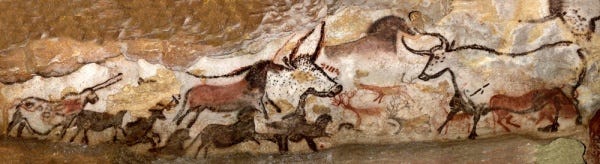

The most common subjects in cave paintings are large wild animals. In European caves these typically include aurochs (wild cattle), bison, horses, deer, ibex, mammoths, and big cats, animals that were significant to hunter-gatherers. Chauvet (France) is notable for depicting species that soon became extinct in Europe (e.g. woolly rhinoceros, cave lions), while Lascaux shows deer, horses, and bulls, and Altamira’s “polychrome ceiling” is famous for painted bison. In Asia and Africa, cave art features local fauna: for example, Sulawesi paintings show native warty pigs and anoas, and Bhimbetka’s shelters include tigers, deer and water buffalo. In the Americas, such as at Las Manos, animals like guanacos and fish appear alongside numerous hand stencils.

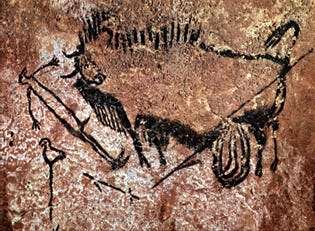

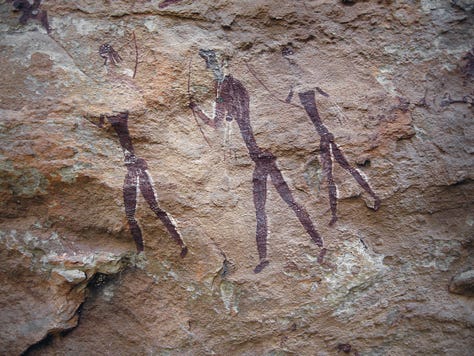

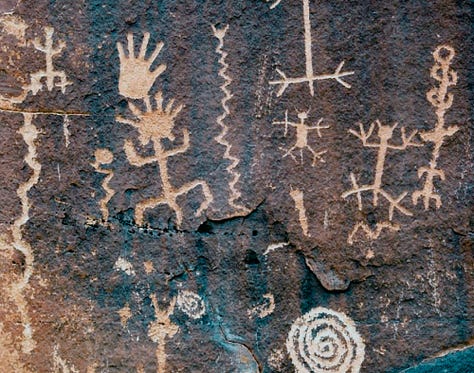

Human figures are relatively rare and usually stylized (stick figures or silhouettes). When present, they often serve as secondary elements or are shown in action (hunting or dancing), not usually as detailed portraits. One famous motif is the hand stencil or handprint: about two-thirds of cave sites worldwide include human hands (often left hands) imprinted on the wall by spitting pigment over them. These handprints are effectively anonymous signatures, hinting at group identity. Other abstract symbols and patterns (dots, lines, grids, and geometric shapes) occur frequently, though their meaning is unclear.

The themes represented in cave paintings are diverse but often follow strikingly similar patterns across regions. Animal imagery is perhaps the most prevalent, with notable examples including herds of horses and bison at Lascaux, depictions of extinct megafauna such as mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses at Chauvet, and deer and goats rendered in the Bhimbetka rock shelters. Human-related imagery also appears, though more sparingly; among the most iconic are the hand stencils found in Cueva de las Manos in Argentina and Chauvet in France. Occasionally, representations of hybrid or symbolic human forms, such as partial “Venus” figures, are found, including two such examples at Chauvet. Abstract marks are another frequent motif: dot clusters, zigzags, and cruciform signs are commonly found in French and Spanish caves. As The Guardian notes, decorated caves around the world consistently exhibit recurring motifs, including handprints, abstract lines and dots, and large animals, suggesting a shared symbolic language or cognitive impulse among prehistoric peoples.

Cave painters tended to focus on the wildlife around them and symbolic marks. Notably, some prey animals (e.g. reindeer) are underrepresented even where hunted, suggesting artists chose images for special reasons, not mere record-keeping. The contrast, many beasts, few humans, itself is a recurrent theme: as archaeologist Jean Clottes puts it, “humans were not at the center of the stage” in Paleolithic art, which overwhelmingly centers on animals.

Why did prehistoric people paint these images? Scholars have proposed many interpretations, but no single purpose is definitively proven. The paintings are rich in symbolism, and likely served multiple cultural functions. One common hypothesis is “hunting magic”; by depicting game animals, hunters could ensure fertility of the herds or success in future hunts. For example, drawing bison before a hunt might have been part of a ritual to exert power over prey. Another idea is spiritual or shamanic ritual: cave art often appears in deep, hidden recesses, perhaps the domain of shamans or ritual specialists. Some scenes (like the famous Sulawesi pig hunt mural) may represent mythic or trance visions. The presence of therianthropic figures (half-human, half-animal) in sites like Chauvet suggests belief in spirit helpers or transformation rites.

Others argue for social or communicative roles. Cave paintings might record communal myths, mark group territories, or reinforce social cohesion. Alistair Pike and colleagues suggest scenes like the Sulawesi mammal hunt could be narrative storytelling, illustrating a specific event or legend. Symbolic thinking is evident: even Neanderthals in Spain created abstract hand stencils 64,000 years ago, implying language-like cognition. It is plausible that art functioned as a mnemonic aid or “message” for other group members. Other proposed functions include teaching or initiation (painting animals as a visual hunting lesson), or fertility/earth-mother rituals (though solid evidence is lacking).

In essence, many interpretations coexist. Cave art likely had diverse meanings: it could be a form of sympathetic magic related to hunting, a spiritual experience (shamanism or ancestor worship), a way of encoding knowledge or stories, or even “art for its own sake” reflecting aesthetic expression. As one summary notes, theories range from practical (documenting predators and prey for education) to religious (storytelling, entertainment, rituals). Crucially, the symbolism in the images provides insight into prehistoric worldviews: for example, animals clearly held profound importance in those societies. Yet without written records, interpretations remain hypotheses supported by context and anthropology rather than definitive facts.

Determining the age of cave paintings is challenging but essential for placing them in prehistory. Most techniques rely on dating either the pigments themselves or associated materials. Radiocarbon dating can be applied when charcoal or organic binders are present, or by dating soot from torches used inside caves. Early attempts yielded many dates (e.g. 80+ samples in Iberia by 2011), but researchers caution that contamination or layered deposits can “produce misleading results”. For instance, debris falling on top of paintings can skew C14 dates.

A major advance has been uranium-thorium (U-Th) dating of mineral deposits (calcite layers) that formed on top of images. Since calcite contains uranium but no carbon, it can be dated up to 450,000 years ago without removing pigment. In practice, scientists sample tiny speleothem crusts overlaying a painting: the date gives a minimum age for the art beneath. Using this method, an iconic result was obtained in Spain: a red disk in El Castillo cave was dated to >40,800 years ago (using overlying calcite), making it one of Europe’s oldest known artworks. Even more remarkably, a 2018 Spanish study applied U-Th to Maltravieso cave’s paint and found a minimum age of 66,700 years – far older than Homo sapiens’ arrival in Europe, implying Neanderthal authorship. These findings push cave art’s origins well into the Middle Paleolithic and have reframed human evolution debates.

Overall, the chronology of cave art centers on the Upper Paleolithic (roughly 40,000–10,000 years ago). Many well-known sites date to the Upper Paleolithic/Magdalenian era: e.g. Lascaux (~17–22 kya), Altamira (painted ~36 kya), Chauvet (~32 kya). Radiocarbon and U-Th dating largely concur that major bursts of art coincide with cold (glacial) periods when hunter-gatherers flourished in Europe. (Chauvet, for instance, has two Aurignacian panels at ~32–30 kya.) These dates align cave art with peak human cultural development in prehistory. Researchers continue to refine dating: for example, new radiocarbon on torch soot and pigment, and more U-Th samples, are narrowing age ranges. In all, dating evidence places cave paintings as ancient artifacts, created between 10,000 and 40,000 years ago (and some possibly older).

Cave paintings are extremely vulnerable, and preserving them is a major concern. Caves provide stable microclimates, which helped preserve the art for millennia, but even slight changes can be disastrous. Some caves closed soon after discovery to halt decay. For example, Lascaux was opened to tourists in 1948 but shuttered by 1963 when artificial lighting and carbon dioxide from visitors caused algal and fungal blooms. Similar crises occurred at Altamira (closed to the public by the 1970s) and other sites. Today, most original Painted Caves are protected by strict controls: entrances are sealed or alarmed, lighting is carefully regulated, and any human access is limited to essential experts. UNESCO and national authorities often oversee this. The Cave of Altamira is now typically visited via timed group tours only, with limits on group size and duration. In extreme cases, replicas have been built: e.g. Lascaux II/IV (1983 and 2016) and Chauvet 2 (Caverne du Pont-d’Arc) (2015) allow public viewing of facsimiles while keeping originals untouched.

Cave paintings face a number of serious threats that require careful conservation responses. One major threat is human impact: body oils, carbon dioxide, heat, and moisture introduced by visitors can create an environment conducive to microbial growth. To address this, conservation plans often enforce strict visitor limits and rely on guided tours to reduce the risk of contamination. For example, UNESCO reports that the Cave of Altamira now only permits controlled group visits with guides and fixed carrying capacities to minimize human impact. Biological growth poses another danger, as changes in environmental conditions can allow algae, bacteria, and fungi to colonize cave walls. At Lascaux, a well-intentioned ventilation system installed in 2000 inadvertently led to a fungal outbreak. In response, conservation teams now employ targeted biocides, regulate airflow, and conduct continuous monitoring to combat microbial threats. Environmental changes also pose risks: water infiltration, earthquakes, and salt crystallization can all cause damage to cave art. Recent studies have shown that fluctuating weather patterns, particularly cycles of wetting and drying, encourage salt crystal formation that can flake away the surface of the walls. UNESCO has warned that millennia-old rock paintings are increasingly at risk of erosion due to climate change. Finally, vandalism and accidental damage remain persistent threats. In 2022, vandals painted a large Spanish flag over a protected UNESCO site, while careless tourists have scratched or wetted paintings in attempts to photograph them. Such incidents highlight the urgent need for enhanced site security and broader public education to protect these irreplaceable artworks.

Modern conservation uses advanced tools. Digital monitoring (humidity, CO₂ sensors) is standard. Teams create high-resolution 3D scans of cave interiors (see next section) to detect minute changes over time. Preventive conservation is now the norm: as UNESCO notes, each cave site has a management plan involving constant monitoring and minimal physical intervention. International bodies (like UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre) also support research and climate resilience strategies for these sites. The goal is to balance scientific study and tourism with the art’s long-term survival. In sum, cave paintings are preserved through a combination of restricted access, replication (for visitors), environmental control, and cutting-edge documentation.

Cave paintings offer a unique window into Upper Paleolithic life. They reveal not only the fauna but hints of the people who made them. Archaeological evidence shows these artists were mobile hunter-gatherers with complex social structures. For example, excavations at Altamira uncovered Stone Age tools from the Solutrean and Magdalenian periods (c. 18,500–14,000 years ago). These artifacts indicate that successive groups repeatedly used the cave mouth for living and hunting in a landscape rich with red deer, bison, and marine life. The painted animals match the local fossil record, confirming the artists depicted familiar game.

Similarly, Lascaux’s horses, deer and bulls correspond to Ice Age fauna known from that region and era. Bhimbetka’s shelters show that early Indian peoples followed herds of animals and later adopted horseback riding (as seen in later paintings). The placement of art deep in caves, away from daily living areas, suggests ritual significance. Many researchers believe caves were special places, possibly temples or ceremonial halls. There may have been gatherings where rituals or storytelling happened by firelight.

In terms of social structure, cave art implies organized groups with symbolic traditions. The collaborative effort to paint large cave walls indicates coordinated communal activity. The sophistication of the art implies apprenticeship and passing down of techniques over generations. As a cultural artifact, cave art stands alongside contemporaneous portable art (carved ivory figurines and decorated tools) as evidence of a highly symbolic Paleolithic society. These societies appear to have revered animals, perhaps viewing them as spiritual entities or clan symbols. The near absence of weapons or mundane daily scenes in the art highlights a focus on the sacred or important aspects of life rather than routine events.

As historian Sarah Wright notes, even Neanderthals, long thought devoid of symbolism, were making abstract cave marks around 64,000 years ago, implying language and culture were already evolving. Thus cave paintings form part of a broader human heritage: they inform us about diet (which animals were hunted), technology (evidence of oil lamps, pigments, scaffolds) and beliefs (spiritual or mythic imagery). Cave art is embedded in the cultural life of prehistoric peoples; they are the murals of Paleolithic society, reflecting its economy (hunter-gathering), spirituality, and social collaboration.

While cave art shares global traits, distinct regional styles emerged, influenced by local culture and ecology. In Western Europe (France/Spain), the so-called Franco-Cantabrian style is famous for polychrome naturalism. Artists used multiple colors and shading to render animals with volume and motion (e.g. Lascaux’s “Chinese Horses” panel). They often composed dynamic herds or hunting scenes across large wall panels. In contrast, Central Asian rock art (e.g. Mongolia, Siberia) often emphasizes single large figures and stylized motifs, reflecting steppe ecology (e.g. deer, ibex). The San rock art of southern Africa (much later in time) features slender human and eland figures painted in white and red, often illustrating trance dances and mythic narratives.

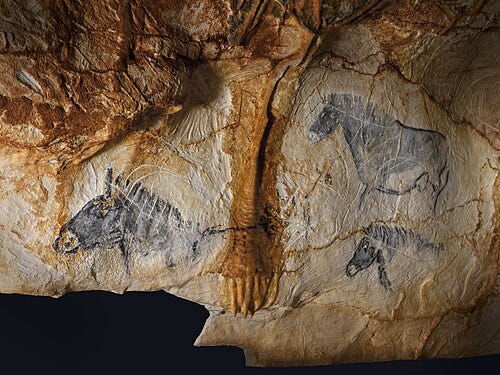

In India (Bhimbetka), the style is multi-period. Early paintings are reddish silhouettes of antelope, boar, and horses; later ones (Mesolithic/Chalcolithic) use multiple colors and depict human dancers, deer herds, and eventually Bronze Age horsemen. Northern African rock shelters (Tassili) show plump cattle and faint line figures, a style quite different from European art. Even within Europe, there is variation: Chauvet’s art (France) is noted for bold engraved lines and chiaroscuro in red/black, and for unusual predators (lions, hyenas), whereas Spanish Levantine art (open shelters) tends toward schematic red-ochre bison and horses drawn more simply.

Some stylistic differences arise from environment; cave shape and surface determined how art was placed. In deep, damp caves, paint has vivid brightness; in dry open shelters, images often fade to monochrome. Scholars also see regional motifs: e.g., a “tectiform” (cross-hatched motif) appears in many Mediterranean caves but not in Africa. Modern analyses suggest that while broad themes (big game, humans, hands) recur everywhere, local conventions (art tools, color palette, composition) yield distinct “schools” of cave art. As a UNESCO summary notes, despite the parallels, each region’s paintings are “unique testimonies to different prehistoric communities,” reflecting varied traditions even within the Paleolithic artistic phenomenon.

The scientific study of cave art began in earnest in the 19th century. In 1879, the Cave of Altamira (Spain) was discovered by Modesto Cubillas and investigated by amateur archaeologist Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola. Their 1880 publication first proposed a prehistoric age for the art, but this claim sparked fierce skepticism among experts, who initially dismissed it as forgery (due to prevailing beliefs that early humans lacked imagination). It took over two decades and the discovery of more sites before Altamira’s authenticity was accepted (an event famously summarized by Émile Cartailhac’s 1902 “mea culpa”).

In France, other major finds followed. In 1940, four teenagers led by 18-year-old Marcel Ravidat stumbled upon the Lascaux cave. They uncovered over 600 paintings, including the famous Hall of Bulls, dating to ~17–20 kya. Lascaux’s importance was immediately recognized; researcher Henri Breuil was invited to authenticate it, and he later became a champion of Paleolithic art. Mid-20th-century scholars like Breuil and later André Leroi-Gourhan pioneered systematic study: Breuil examined and categorized sites, while Leroi-Gourhan (1911–1986) developed theories of iconography (noting patterns like “masculine/feminine” animal pairs) and stylistic phases (Aurignacian through Magdalenian) in cave art.

The Chauvet cave was found much later: on December 18, 1994, three speleologists (Chauvet, Brunel-Deschamps, Hillaire) discovered a massive decorated cavern in Ardèche, France. Its Upper Paleolithic paintings, dated ~32–30 kya, were the oldest and best-preserved known, prompting a new wave of research (including expedition documentaries). Other significant discoveries include Cosquer Cave (Marseille, found 1985, now underwater entrance) and galleries at El Castillo and La Pasiega (northern Spain) containing the oldest pigment-dated art (40–65 kya).

From the first finds to today, scholarly perspectives have evolved. Early 20th-century researchers viewed cave art largely as hunting propaganda or sympathetic magic. By the late 20th century, it was understood as complex symbolic expression. Today, multidisciplinary teams (archaeologists, chemists, climatologists) study caves. Ethical and conservation concerns (e.g. closing sites to the public) now shape discovery. The history of study moved from initial denial of authenticity to enthusiastic preservation and high-technology research, but the art itself remains the same silent testimony of prehistory.

Recent decades have seen revolutionary technologies applied to cave art. Digital 3D scanning and imaging now document paintings at microscopic detail. For example, Lascaux has been fully laser-scanned: a 2014 project used a sub-millimeter resolution 3D scanner capturing ~500,000 points per second, producing color images of 25–32 million pixels. This ultra-high-resolution model enables virtual tours and scientific study without human presence. It formed the basis for Lascaux IV’s facsimile and climate simulations. Similarly, Chauvet and other caves have been photogrammetrically mapped; these digital archives help monitor changes and create VR exhibits for education.

Non-invasive chemical analysis (portable X-ray fluorescence, Raman spectroscopy) reveals pigment composition without sampling. For instance, these tools distinguish mineral ochres and trace mixtures, informing us how artists mixed colors. Reflectance imaging (infrared, UV) can uncover faded or overpainted details invisible to the eye. Portable drills equipped with fiber-optic scopes allow access to narrow fissures to photograph art. In some cases, small pigment micro-samples are taken for radiocarbon or U-Th dating (with extreme care to avoid damage).

Virtual Reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are used to engage the public. The French Centre international de l’art pariétal (“Lascaux IV”) uses projection and VR to simulate visits. Digital databases compile rock art worldwide (e.g. Traceological databases in Europe). Artificial intelligence and pattern-recognition software are beginning to assist in motif classification, by scanning caves for handprints or counting species frequency automatically.

These technologies profoundly impact research: they allow scholars to study fragile caves remotely and to share sites globally without physical travel. They also enhance conservation: 3D models let scientists simulate the microclimate of caves and test interventions in silico. In sum, modern tech has transformed cave art from static relics into dynamic digital records, broadening both analysis and public access.

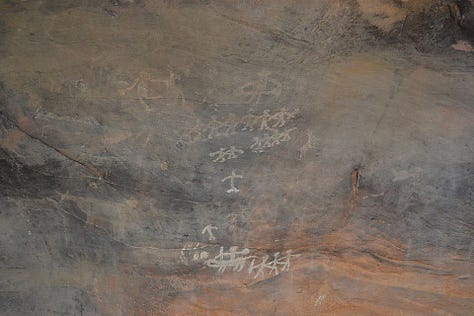

Cave paintings are one expression of Paleolithic art, alongside rock engravings (petroglyphs) and portable art. Petroglyphs, images pecked or carved into rock faces, often appear in open-air shelters and have different themes (e.g. cupules, geometric patterns, or more recent symbolic carvings). Portable art includes carved figurines (such as the Venus of Willendorf, ~28 kya) and decorated tools or bone plaques. These portable objects were often made from ivory, stone or bone and could be carried; they usually depict animals or human forms on a smaller, 3D scale. By contrast, cave art is fixed to place and tends to be larger and more schematic.

Despite differences, all these art forms share the mark of symbolic thinking. For instance, engraved and painted patterns likely held meaning beyond mere decoration. Cave murals can be related to these other arts: some niches in caves contain prehistoric statuettes or decorated bones, suggesting an overlap of artistic tradition. Many researchers see a continuum: a painted bison on a wall, an engraved reindeer antler, and a carved figurine all reflect the same impulse to symbolically record important subjects. In that sense, cave painting fits into a broad development of human artistic expression. Archaeologists note that “rock art, painted or engraved, provides an enduring glimpse into prehistoric life”, and the cognitive leap to create any of these (whether on cave walls or bone) was a shared step in human evolution. However, cave paintings are often the most spectacularly preserved and richly detailed of these art forms, making them iconic representatives of our earliest art.

The appearance of cave art marks a key moment in human cognitive evolution. The capacity to create and comprehend symbolism is a hallmark of modern cognition. By depicting non-utilitarian images, early humans demonstrated advanced planning, memory, and abstract thought. In fact, the presence of cave art is often cited as evidence of behaviorally modern humans. Discoveries of very ancient art push this even further: for example, hand stencils and simple shapes dated to ~64–65k years ago in Spain show that Neanderthals also engaged in symbolic painting. This implies that the cognitive abilities (symbolism, possibly language) required for art were present not only in Homo sapiens but in Neanderthals too.

Thus, cave art is intertwined with questions of human evolution. The capacity to paint suggests complex social communication and possibly ritual. Jean Clottes argues that Paleolithic cave art shows us “the essential role played by animals” and the early humans’ perception of their place in the world. The very fact that people could light fires deep in caves, build scaffolds, and work in darkness to create these images suggests significant cultural and intellectual development. As one science writer notes, art may have been among our ancestors’ earliest forms of communication, hinting at proto-language. In short, cave paintings are not just pretty pictures; they are archaeological evidence that by ~40,000 years ago, humans (and perhaps Neanderthals) possessed the self-awareness and creativity that set us apart from other animals. They represent a cognitive milestone; evidence of abstract thinking, planning, and shared culture in prehistoric mankind.

Studying cave art poses unique difficulties. First, dating and authenticity can be fraught. Radiocarbon results for a single image may vary widely depending on sample and contamination. One archaeologist notes that “wildly varying radiocarbon dates from the same painting” are not uncommon. This makes establishing exact chronologies tricky. Interpreting the meaning of images is also speculative. We lack written explanations, so every theory (ritual, magic, narrative) is a hypothesis that can be hotly debated. For example, the claim that a 42,000-year-old painting in Spain was made by Neanderthals was challenged because it relied on dating cave debris rather than the paint itself. Such controversies illustrate how easily evidence can be misinterpreted.

Another issue is preservation vs. study. Direct sampling (even of mineral overgrowths for U-Th dating) involves taking material from a delicate site, which some argue is unethical if it risks damage. The accessibility of sites adds complexity: many paintings are high on walls or in narrow pits, limiting photography and analysis. Data transparency can also be a problem; for example, Lascaux’s scientific results were initially kept from some researchers, prompting UNESCO to demand open data sharing.

Finally, there are practical obstacles; caves are dark, cold, and hazardous. Researchers can spend only limited time inside (hours total in Chauvet, for instance). The very act of documenting can endanger art (flash photography can alter pigments, bodies in caves raise humidity). All these factors, dating uncertainties, interpretive ambiguity, and preservation constraints, mean cave painting research requires extreme caution. New non-invasive methods help, but some “big questions” may remain open simply because definitive proof (like a written explanation from the artist) is impossible to obtain.

Cave paintings raise important ethical questions about access, ownership, and heritage. There is no single “owner” of these ancient images; they are part of humanity’s shared heritage. Most major sites are on national land or protected as UNESCO World Heritage sites (e.g. Lascaux, Altamira, Bhimbetka). UNESCO explicitly calls places like Altamira “masterpieces of creative genius” and “an extraordinary testimony to a cultural tradition now extinct”, emphasizing collective stewardship. Legally, modern nations and international bodies manage the sites; in practice, governments or heritage agencies (often with input from local communities) set access rules.

Debates sometimes arise over how to balance public interest versus preservation. Is it ethical to allow tourism if it risks damage? Most countries have erred on the side of protection: for example, the original Lascaux cave remains closed, with only a replica open to the public. Altamira’s paintings are similarly off-limits, seen only via replicas or limited guided tours. This reflects a principle that these fragile paintings must not be subjected to uncontrolled exposure or commercialization. At the same time, there is an ethical duty to educate: many argue facsimiles, virtual tours and high-quality photographs should make cave art as accessible as possible without harming the originals.

Another ethical aspect is local and indigenous respect. While Paleolithic cave art predates any modern ethnicity, in some cases local cultural or spiritual traditions have emerged around sites. For instance, Aboriginal Australian communities treat certain rock art sites (though often younger than Paleolithic) as sacred, and their permission is needed for research. In general, however, prehistoric cave art is regarded as part of a universal prehistoric heritage rather than owned by any one group.

Finally, handling and publishing research data involves ethics. Scientists must ensure findings are accurate and responsibly communicated, avoiding sensationalism. The controversy over Neanderthal art shows how easily the public can be misled by overclaiming. In recent years, UNESCO and research councils emphasize that cave art studies follow strict conservation ethics: minimal sampling, peer review, and respect for site preservation. In summary, the ethics of cave art revolve around protecting a nonrenewable heritage while permitting responsible study and public appreciation, guided by principles of stewardship and respect for the human legacy these images represent.

Cave paintings continue to captivate and inspire modern society. In art and literature, they are seen as the roots of creative expression. Famous artists have directly engaged with Paleolithic motifs; Pablo Picasso was profoundly influenced by Lascaux’s images, famously remarking that after seeing them “we have invented nothing!”. He and others (e.g. Jean Cocteau, Stephen Alvarez) created works echoing cave themes. Contemporary artists continue this legacy; the French painter Pierre Soulages cites an Altamira bison as pivotal to his use of black light and shadow. The aesthetic power of cave animals resonates in sculpture, film, dance and even video games.

Cave art also appears in modern storytelling and education. Jean Auel’s “Earth’s Children” novels (e.g. The Clan of the Cave Bear) brought them into popular fiction. Documentaries (like Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams) and museum exhibits (e.g. Lascaux and Chauvet facsimiles worldwide) introduce millions to these images. In academia, cave art shapes disciplines from anthropology to neuroscience: neuroscientists study brain activity as people view prehistoric art, and education curricula use cave paintings to teach evolution and art history.

Today’s global heritage and tourism industries revolve around prehistoric art too. Sites like Altamira and Bhimbetka are UNESCO World Heritage destinations that draw international visitors (virtually or via replicas), making these Paleolithic images part of modern identity. Many see cave paintings as a reminder that humans have long been storytellers and artists. The enduring fascination is captured by a Google Arts & Culture summary: prehistoric art “portrays subjects and issues that speak across the millennia to other fellow artists”. In short, cave art’s legacy lives on – as masterpieces of human creativity that continue to influence contemporary culture and remind us of our shared past.

Several key cave painting sites stand out for their historical significance, artistic achievement, and contributions to our understanding of prehistoric cultures. Lascaux, located near Montignac in the Dordogne region of France, was discovered in 1940 and contains over 600 paintings; most of which are strikingly realistic renderings of Ice Age animals such as horses, deer, and bulls. These images correspond closely with the local Pleistocene fauna and demonstrate a remarkable level of sophistication, particularly in scenes like the "Hall of the Bulls," where some figures reach four to five meters in length and feature careful shading. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979, Lascaux was closed to the public in 1963 due to damage from excessive visitation. Today, high-fidelity replicas (Lascaux II and IV) allow the public to experience the art while preserving the original. Archaeological evidence indicates that the cave's entrance was used by humans equipped with tools from the Magdalenian period. Lascaux has since become emblematic of Paleolithic art and is often cited as a pinnacle of early human creativity.

Altamira, another renowned site, is located near Santillana del Mar in Cantabria, Spain. Discovered in 1868, Altamira's main hall features a famous polychrome ceiling that depicts a herd of bison alongside horses, deer, and handprints. These paintings date to the Upper Paleolithic period, approximately 36,000 years ago. Altamira was the first European cave found to contain prehistoric paintings, and although its authenticity was initially contested, it was later validated and played a foundational role in establishing the study of Paleolithic art. Excavations within the cave revealed Solutrean and Magdalenian artifacts, indicating successive periods of use. In 1985, UNESCO inscribed Altamira and its associated northern Spanish caves as World Heritage Sites. Like Lascaux, the original cave is now closed to the public to prevent deterioration, with visitors instead viewing a museum replica of the bison ceiling.

In South Asia, the Bhimbetka rock shelters in Madhya Pradesh, India, represent the region’s most extensive Paleolithic art complex. Inhabited since roughly 100,000 years ago, more than 750 shelters contain paintings ranging from the Mesolithic through historic periods. The earliest artworks, dating to around 10,000 BCE, depict wild animals such as tigers and deer, human hunters with bows, and ritualistic dance scenes. Later periods, including the Chalcolithic, added imagery of horses and elephants, while the notable "Warrior Cave" features figures on horseback dated to between 10,000 and 4,000 BCE. Bhimbetka’s art showcases a wide stylistic range, from red-ochre silhouettes to polychrome compositions. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003, Bhimbetka offers a rare visual continuity that spans from the lives of early hunters to the dawn of historical kingdoms.

Together, these sites exemplify the diversity and cultural richness of prehistoric cave painting. Lascaux’s dynamic herd scenes, Altamira’s advanced pigment use, and Bhimbetka’s long, layered artistic record collectively demonstrate how cave paintings capture different prehistoric traditions, reflecting the shared impulses and regional distinctions of early human societies across the globe.

Building on the symbolic significance of cave paintings, scholars have proposed various hypotheses regarding their function, ranging from practical to spiritual interpretations. One of the most enduring theories is that of hunting or ritual magic, which suggests that depictions of prey animals were part of sympathetic magic intended to ensure successful hunts. Ethnographers have likened this practice to shamanistic rituals, where creating images is believed to influence reality. Another perspective views the art as communicative or educational; in this interpretation, prehistoric artists may have used visual narratives to teach young hunters, record notable events, or share knowledge about seasonal animal movements. Some scholars have likened these paintings to early comic strips or storyboards that preserved collective memory across generations.

A third hypothesis emphasizes the symbolic or religious function of cave art. Many researchers believe that caves served as sacred spaces, and the act of painting deep within them was part of initiation rites or spiritual communion. In this view, animals may have represented clan totems or spiritual guides, and the repeated visits to painted sites, along with associated ritual items such as bones and oil lamps, suggest ceremonial use. Another theory posits that cave paintings functioned as social or identity markers, akin to tribal emblems, which allowed groups to assert territorial claims or reinforce alliances. Finally, some propose that the motivation behind cave painting was simply artistic or playful; a manifestation of the innate human drive to create. While this explanation is more difficult to confirm without cultural context, it remains an important consideration within the broader spectrum of interpretive theories. Taken together, these hypotheses illustrate the complexity and richness of prehistoric life, underscoring the likelihood that cave art served multiple overlapping purposes depending on time, place, and community.

These functional hypotheses are not mutually exclusive; cave art might have served different purposes at different times or places. In any case, each theory underscores the pictures’ potential roles in prehistoric society: as part of ritual practice, cultural education, communication, or simply the human impulse to symbolize. The diversity of imagery, from handprints to complex hunts, suggests multiple layers of meaning and use, leaving us with compelling but tentative insights into why our ancestors painted their world.

Cave art has survived for millennia, but past and present climate factors have influenced its fate. In the past, glacial and interglacial cycles affected where humans lived and what they painted (for instance, many European caves were accessible during lower sea levels in Ice Age). Changing ecosystems likely influenced subject matter (for example, megafauna in glacial times). More directly, climate change poses threats to existing cave art today.

Warming temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, and extreme events can damage cave walls. UNESCO warns that “millennia-old rock paintings….are at risk of erosion” due to climate impacts. For instance, increased humidity swings cause salt (halite) to crystallize on cave surfaces. A 2021 study of Indonesian caves found salt crystals expanding and contracting with weather cycles, literally flaking the rock and making art vanish inch by inch. Similar salt-driven decay likely threatens caves worldwide, especially in monsoon or Mediterranean climates.

Rising sea levels also endanger coastal cave sites. A subaqueous cave in southern France containing Ice Age marine animal art is gradually being lost as sea level rises, making the paintings unreachable and at risk of dissolution. Elsewhere, intensifying storms or floods could inundate low-lying caves. Even human responses to climate (like groundwater extraction or changes in land use) might alter cave microclimates inadvertently.

Conservationists now include climate modeling in their plans. Some regions are investigating desalination or dehumidification to stabilize caves. For example, Lascaux has advanced climate control systems to prevent condensation. Globally, researchers are mapping vulnerable sites. The key point is that cave art, though ancient, is not immune to 21st-century environmental change, indeed, rapid climate shifts may be the most urgent threat to these artworks since their creation.

Cave paintings continue to matter profoundly in the modern world. They remain our earliest visual records of human imagination and serve as reminders of the deep antiquity of art. These images have shaped our understanding of human history, for example, they decisively showed that early humans had symbolic thought long before the advent of writing. UNESCO language reflects this enduring legacy; cave art sites are “masterpieces of human creative genius” and crucial links to humanity’s past.

Culturally, cave paintings have inspired generations. As Google Arts & Culture observes, they “portray subjects and issues that speak across the millennia”, bridging prehistoric and modern sensibilities. By studying cave art, archaeologists, artists, and philosophers explore timeless themes: our relationship to nature, the origins of belief, and the universality of artistic expression. Even today, people are moved to stand before these ancient works (or their replicas) and feel a connection to “the people of this other, unreachable world”.

In science, cave paintings fuel research into human cognition and culture. They appear in museum exhibits, textbooks, and media worldwide, educating new audiences about early human life. In art, they influence contemporary creators (e.g. Picasso, Soulages) and feature in popular imagery (pictogram logos, movie cave scenes). The continued discovery of new sites keeps pushing back our timelines, showing that the human capacity for art arose even earlier than thought.

Ultimately, cave paintings’ legacy lies in their combination of beauty and mystery. They shape our identity by confirming that the desire to create and communicate images is an innate human trait. As one modern artist put it, beholding these works can humbly convey that “we have invented nothing” beyond what was already expressed in the caves. By connecting us to our distant ancestors, cave art enriches our sense of what it means to be human; a legacy that will endure as long as we continue to ask how art, culture, and history intertwine.

References:

Bahn, Paul G. Prehistoric Rock Art: Polemic and Progress. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Bahn, Paul G., and Jean Vertut. Journey Through the Ice Age. University of California Press, 1997.

Clottes, Jean. Cave Art. Phaidon Press, 2008.

Clottes, Jean, and David Lewis-Williams. The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance and Magic in the Painted Caves. Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

Conard, Nicholas J., et al. Evidence for the Earliest Musical Instruments and Their Implications for the Evolution of Musical Behavior. Nature, vol. 460, no. 7256, 2009, pp. 737–740.

David, Bruno, and Meredith Wilson, editors. Inscribed Landscapes: Marking and Making Place. University of Hawai‘i Press, 2002.

Gárate Maidagan, Diego, et al. The Origins of Parietal Art in the Iberian Peninsula. Science, vol. 359, no. 6378, 2018, pp. 912–915.

Gowlett, John A. J. The Discovery of Fire by Humans: A Long and Convoluted Process. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, vol. 371, no. 1696, 2016.

Henshilwood, Christopher S., et al. Emergence of Modern Human Behavior: Middle Stone Age Engravings from South Africa. Science, vol. 295, no. 5558, 2002, pp. 1278–1280.

Hoffmann, Dirk L., et al. U-Th Dating of Carbonate Crusts Reveals Neandertal Origin of Iberian Cave Art. Science, vol. 359, no. 6378, 2018, pp. 912–915.

Leroi-Gourhan, André. Prehistoric Man: The Myth and the Reality. Thames and Hudson, 1982.

Lewis-Williams, David. The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art. Thames & Hudson, 2002.

McDermott, LeRoy. Self-Representation in Upper Paleolithic Female Figurines. Current Anthropology, vol. 37, no. 2, 1996, pp. 227–275.

Pettitt, Paul. The Palaeolithic Origins of Human Burial. Routledge, 2011.

Pike, Alistair W. G., et al. U-Series Dating of Paleolithic Art in 11 Caves in Spain. Science, vol. 336, no. 6087, 2012, pp. 1409–1413.

Rappenglück, Michael A. Ice Age People Find Their Place in the Cosmos: The Pleiades and Taurus in the Cave of Lascaux. Journal of Scientific Exploration, vol. 11, no. 4, 1997, pp. 471–485.

Rossi, Andrea. Prehistoric Art: Signs and Symbols of the Ice Age. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Prehistoric Sites and Decorated Caves of the Vézère Valley. whc.unesco.org/en/list/85/. Accessed 14 March 2025.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka. whc.unesco.org/en/list/925/. Accessed 14 March 2025.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain. whc.unesco.org/en/list/310/. Accessed 14 March 2025.

Walsh, John. Virtual Reality and the Preservation of Paleolithic Cave Art. Journal of Digital Heritage, vol. 3, no. 4, 2019, pp. 230–244.

Whitley, David S. Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit: The Origin of Creativity and Belief. Prometheus Books, 2009.

Wright, Sarah. Neanderthal Symbolism and the Artistic Mind. Antiquity, vol. 92, no. 366, 2018, pp. 896–911.

The art is astounding and in many ways has never been surpassed.

Uh oh. It is very tempting.