Día de los Muertos is celebrated on November 1st and 2nd, coinciding with the Catholic observances of All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day. This multifaceted tradition honors deceased loved ones, blending pre-Columbian beliefs with Catholic customs. Andrew Chesnut, an authority on the subject, argues that Día de los Muertos serves not only as a day of remembrance but also as a manifestation of cultural identity and resistance against colonial narratives (Chesnut, 2017).

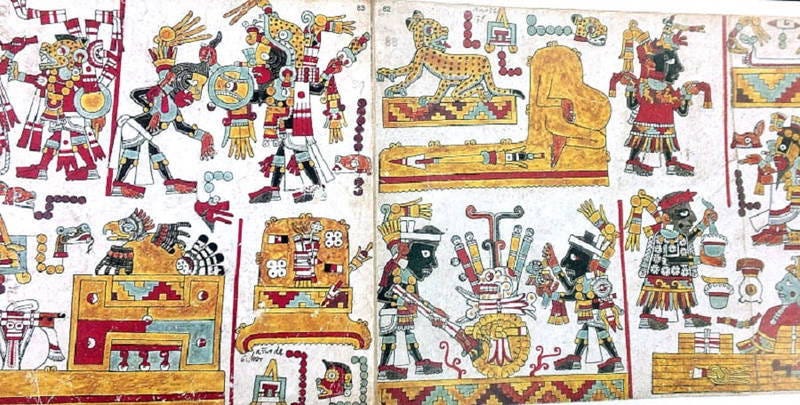

Día de los Muertos has deep roots in ancient Mesoamerican cultures, particularly among the Aztec civilization, which viewed death as a cyclical part of life. The Aztecs honored their ancestors through various rituals, including the creation of skulls and offerings (Miller, 2015). According to Diego Rivera, the Aztecs believed that the spirits of the deceased would return to visit their families, necessitating the preparation of altars and offerings (Rivera, 2003).

Following the Spanish colonization in the 16th century, Catholicism integrated with these indigenous practices, leading to the current celebration that merges both traditions. This syncretism is essential for understanding the contemporary significance of Día de los Muertos, marking it as a time for families to reunite with the spirits of their ancestors. Chesnut emphasizes that the blending of these beliefs demonstrates how indigenous people adapted to colonial influences while preserving essential elements of their culture (Chesnut, 2017).

At its core, Día de los Muertos is about remembrance and celebration. Families construct ofrendas (altars) adorned with photographs, mementos, and favorite foods of the deceased, symbolizing the belief that the dead return to visit their families during this time. Each element of the ofrenda serves a purpose: marigolds attract spirits, candles illuminate the way, and favorite foods nourish the souls of the departed (Nájera, 2019).

Chesnut (2017) asserts that the celebration acts as a powerful means of cultural preservation, allowing communities to maintain their identity amid globalization and cultural homogenization. The holiday underscores the importance of familial bonds and collective memory, emphasizing that death is not an end but a continuation of relationships. According to anthropologist Barbara Bader, this unique approach to death and remembrance reflects a profound cultural attitude towards life, where death is celebrated rather than feared (Bader, 2012).

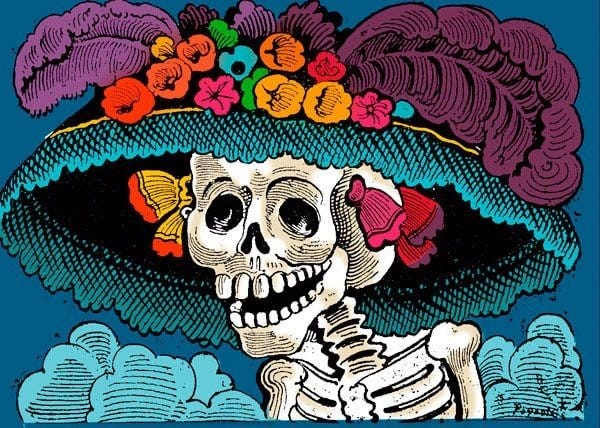

Moreover, figures such as La Catrina (a skeletal female figure dressed elegantly) have become iconic symbols of Día de los Muertos. La Catrina, originally created by José Guadalupe Posada, critiques social class and has evolved into a representation of the celebration itself. Chesnut (2022) explains how La Catrina embodies the fusion of humor and reverence in Mexican attitudes towards death, reinforcing the idea that death is an integral part of life’s journey.

In recent years, Día de los Muertos has gained international recognition, leading to a hybridization of practices. While traditional celebrations remain vital in many Mexican communities, urbanization and globalization have introduced new elements. Festivals, parades, and public altars are increasingly common, with cities like Los Angeles and Mexico City hosting large-scale events that attract participants from diverse backgrounds (Sánchez, 2018).

Chesnut (2022) notes that this globalization has sparked a “cultural renaissance,” as people worldwide seek to connect with Mexican heritage. The incorporation of Día de los Muertos into global cultural consciousness can be seen in various forms of media, including film and literature, which often romanticize the holiday while sometimes oversimplifying its complexities. The Disney film Coco (2017) is a notable example, celebrating the holiday while introducing it to a broader audience.

However, the commercialization of Día de los Muertos poses challenges. As it becomes commodified—through the sale of decorations, costumes, and food—the original significance may be diluted. Chesnut argues that maintaining the authenticity of the celebration amidst its global appeal is crucial for preserving its cultural integrity (Chesnut, 2017). Furthermore, as Jennifer M. Mendez points out, the rise of tourism has led to a transformation of traditional practices, sometimes resulting in a disconnection from their original meanings (Mendez, 2020).

Día de los Muertos serves as a powerful testament to the resilience and richness of Mexican cultural identity. By honoring the dead and celebrating life, this tradition fosters a sense of community and continuity. Andrew Chesnut's contributions illuminate the complexities of the celebration, highlighting its historical roots, cultural significance, and contemporary challenges. As Día de los Muertos continues to evolve in a globalized world, it remains essential for individuals and communities to navigate the balance between honoring tradition and embracing change.

References

Bader, B. (2012). The Living and the Dead: Cultural Memory in Mexican Society. University of California Press.

Chesnut, A. (2017). Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint. Oxford University Press.

Chesnut, A. (2022). Mexico’s Death Trio: La Catrina, Day of the Dead, Santa Muerte. Patheos. Retrieved from [Patheos Article Link](https://www.patheos.com/blogs/andrewschesnut/2017/11/02/mexicos-death-trio-la-catrina-day-of-the-dead-santa-muerte/).

Mendez, J. M. (2020). “Tourism, Heritage, and the Día de los Muertos: Navigating Authenticity in Mexican Culture.” International Journal of Heritage Studies, 26(6), 585-597.

Miller, M. (2015). The Aztec Calendar and the Day of the Dead. Journal of Ethnobiology, 35(2), 324-340.

Nájera, S. (2019). “Día de los Muertos: The Art of Memory.” Cultural Studies Review, 25(1), 53-74.

Rivera, D. (2003). The Aztec World: A History. University of Arizona Press.

Sánchez, A. (2018). “Reimagining Día de los Muertos: Global Influences on Local Traditions.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies, 27(4), 405-423.