Dancing Figures & Red Ribbons: Keith Haring’s Queer Imaginary

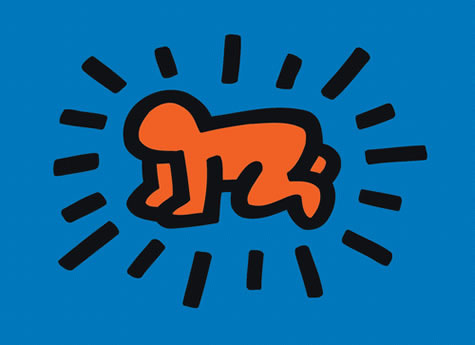

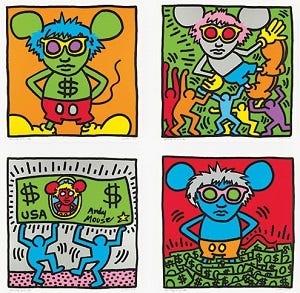

Keith Haring (1958–1990) emerged in the early 1980s as one of New York City’s most influential voices in contemporary art and social activism. From the black-papered walls of the subway to the gleaming facades of gallery spaces, Haring wielded his bold, graphic language to confront issues ranging from sexuality to AIDS awareness, from racial injustice to drug epidemics. Central to his visual lexicon was the Radiant Baby, a motif of simplicity and hope first sketched in chalk tunnels around 1982–83 and later adapted into large-scale projections and a rooftop mural on the RCA Building in 1984. In 1986, his collaborative silkscreens with Andy Warhol, collectively known as Andy Mouse, melded two generations of pop-driven imagery into a playful queer commentary on celebrity culture.

Born on May 4, 1958 in Reading, Pennsylvania, Haring’s childhood fascination with cartoons and commercial illustration laid the groundwork for the kinetic simplicity that would define his art. Immersed in Mad magazine and Disney comics, he learned early the power of immediate, iconic imagery. After high school, he attended the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh (1976–78), where he mastered technical drawing but chafed under its constraints. It was here that he produced Magic (1977–78), a series of experimental posters layering vivid color fields, a prescient testbed for the visual vibrancy that marked his later murals.

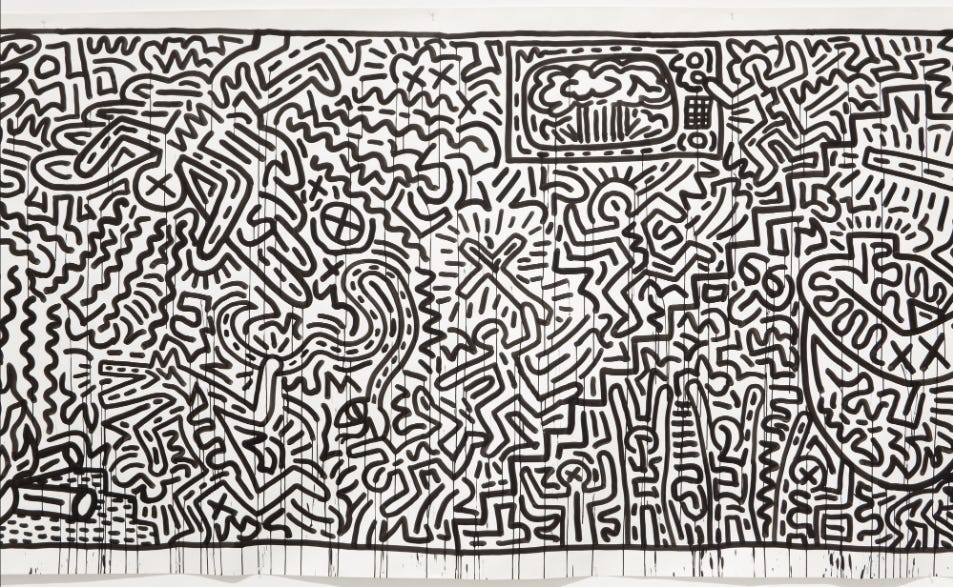

In 1978, seeking freedom and community, Haring enrolled at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York City. The downtown scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s was electric: Haring befriended Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf, collaborated in the Colab network, and became a fixture at Club 57. Inspired by subway graffiti and fueled by a do-it-yourself ethos, he began to chalk spontaneous drawings on the black-papered ad panels of the city’s subway stations. Over the next five years, Haring completed more than five hundred of these subway drawings, converting the daily commute into an open-air gallery and democratizing access to contemporary art. His first institutional nod came in 1982, when the Museum of Modern Art invited him into its Projects series with Untitled (1982), cementing his transition from street artist to museum-recognized figure.

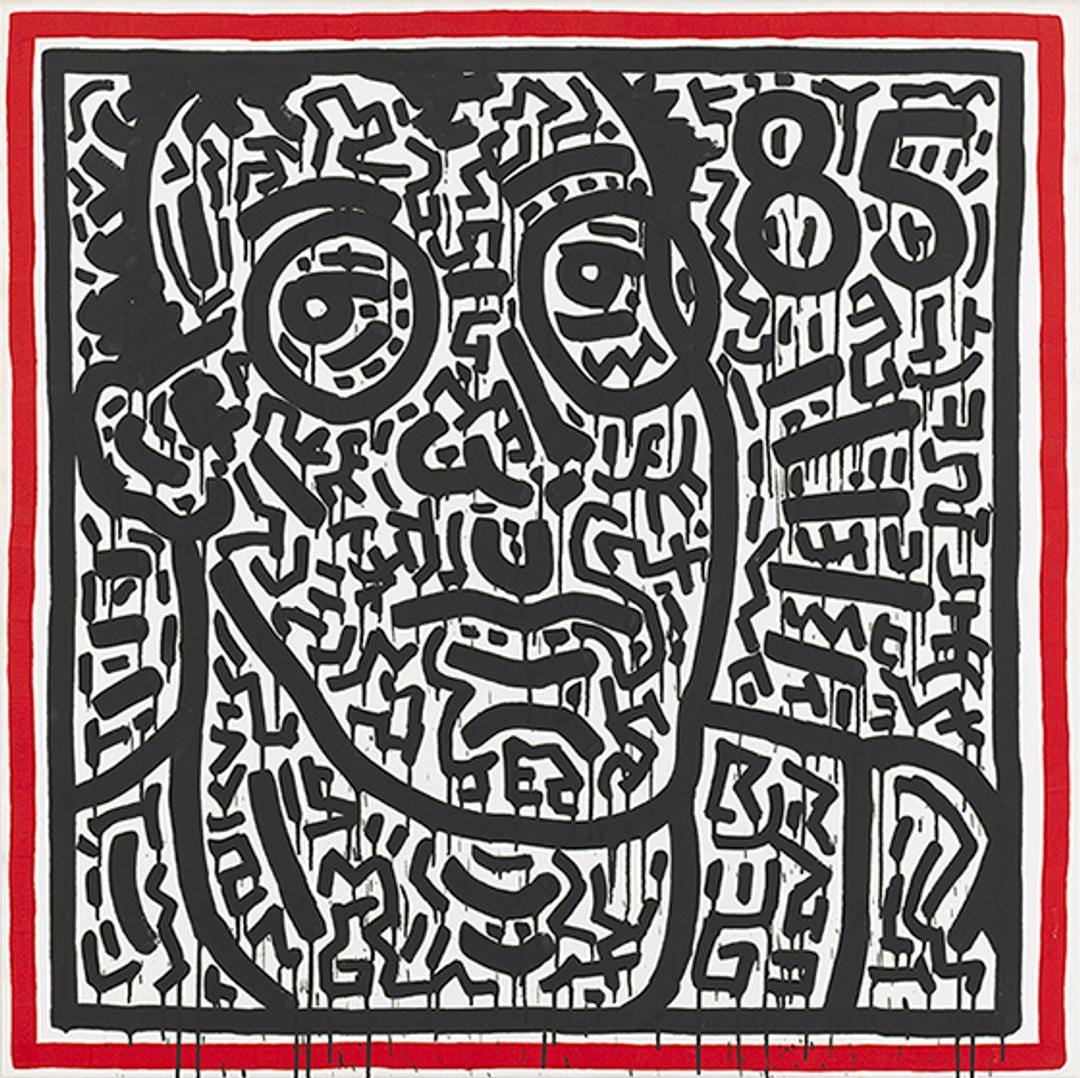

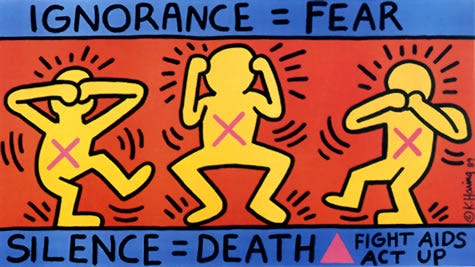

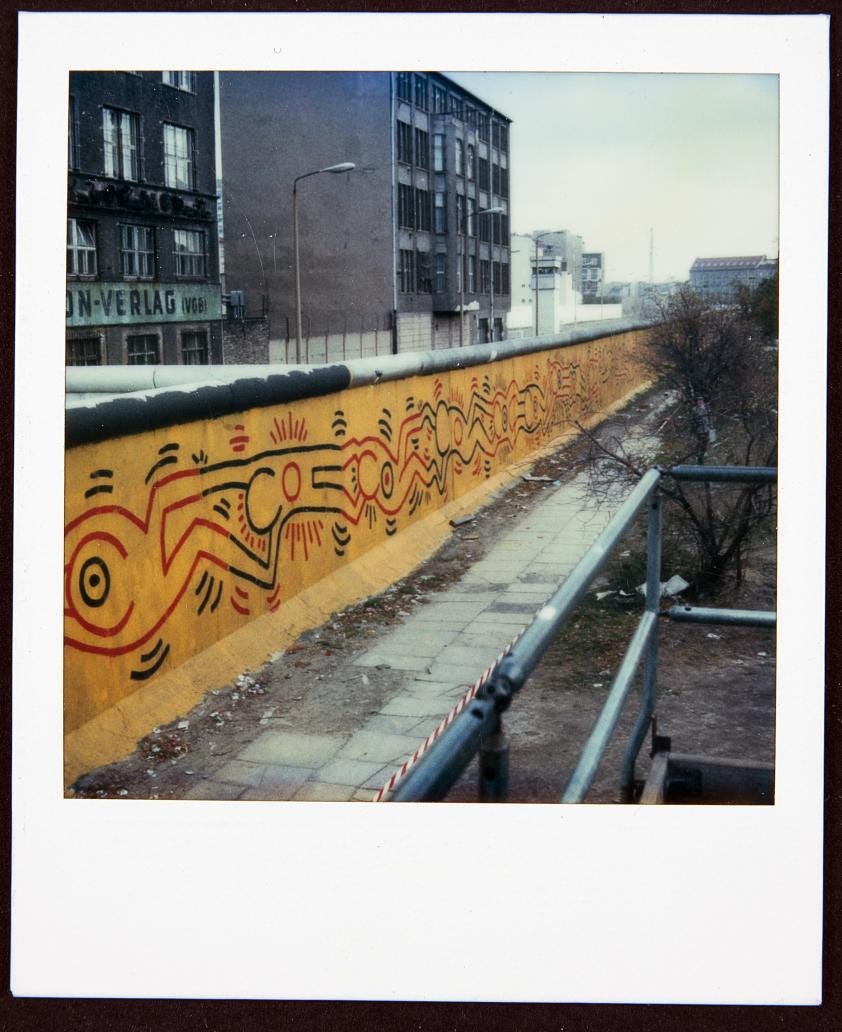

While Haring’s early subway work was largely apolitical, by the mid-1980s he embraced his identity as a gay man and the social urgency it carried. His private journals, filled with reflections on desire, community, and hope, offer a candid roadmap to his creative evolution. In Self-Portrait (1985), Haring reduces his likeness to a single, monumental head rendered in thick black lines, its stylized eyes and mouth emerging from a frenetic field of his own calligraphic motifs. The entire composition is contained within a hand-painted red border, whose paint drips onto the white ground, emphasizing the work’s raw immediacy. When AIDS ravaged New York’s LGBTQ communities, Haring refused to turn away. He painted Ignorance = Fear/No Fighting (1987), a billboard variant that merged anti-Apartheid and AIDS-awareness messaging, donating the proceeds to activist groups such as ACT UP. That same year, aware of the need for sustained support, he founded the Keith Haring Foundation, vesting all royalties and profits to fund AIDS organizations and children’s programs. His 1989 mural in Barcelona, Todos Juntos Podemos Parar el Sida, featured entwined figures encircling a red ribbon, a universal call for compassion and collective action.

Arguably Haring’s most enduring emblem, the Radiant Baby first flickered to life in subway tunnels before exploding onto public walls and stages. Composed of a simple crawling infant silhouette surrounded by emanating rays, the motif encapsulates innocence, hope, and the possibility of renewal. Installed as a rooftop mural on the RCA Building in 1984 and projected in light-shows, Radiant Baby served as a beacon of optimism amid the grim realities of the AIDS crisis. Its repeated appearance across media, from paintings to T-shirts, underscored Haring’s belief that art should transcend gallery walls and reach everybody.

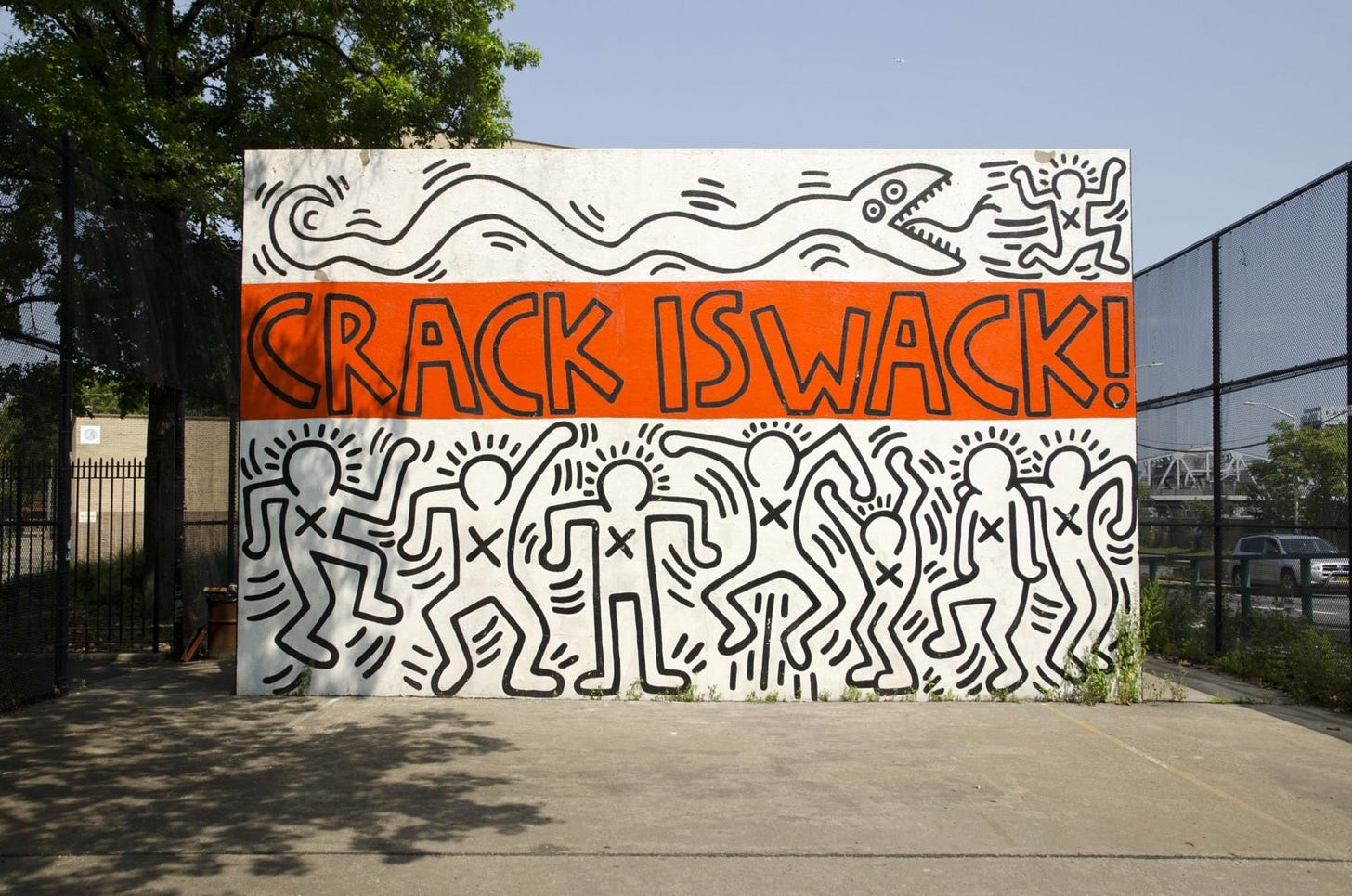

In October 1986, after completing an unauthorized mural on a handball court adjacent to the FDR Drive, Haring was commissioned by New York City Parks to recreate the work as Crack Is Wack. With its bold, cartoon-inflected lettering and animated figures, the mural confronted the city’s crack-cocaine epidemic head-on. Though its primary message was anti-drug, Crack Is Wack also resonates with LGBTQ histories of substance dependency, reflecting layered social vulnerabilities. Its bright palette and clear iconography demonstrate Haring’s knack for transforming public spaces into sites of urgent civic discourse.

Commissioned in 1989 by the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan, Haring’s The Life of Christ (completed February 1990) takes the form of a monumental triptych altarpiece cast in bronze and plated in white gold. Across its three panels, he distills fifteen key episodes, from the Annunciation and Nativity through the Crucifixion to the Resurrection and Ascension, into his signature rhythmic lines and densely packed silhouettes. The gleaming white-gold surface becomes a field for Haring’s animated halos, simplified figures and radiating marks, forging a dialogue between medieval iconography and the vernacular energy of New York street art. Installed on the cathedral altar just weeks before his death, the work embodies a final testament to universal compassion, renewal and spiritual hope.

As part of the Artists United Against Apartheid campaign, Haring designed the Free South Africa poster to galvanize public opposition to South Africa’s racial segregation. Its stark depiction of chained figures bursting free beneath the slogan paralleled the struggles for both racial and sexual liberation. Through this piece, Haring drew an explicit line between global systems of oppression and the fight for LGBTQ equality, reinforcing art’s capacity to foster solidarity across movements.

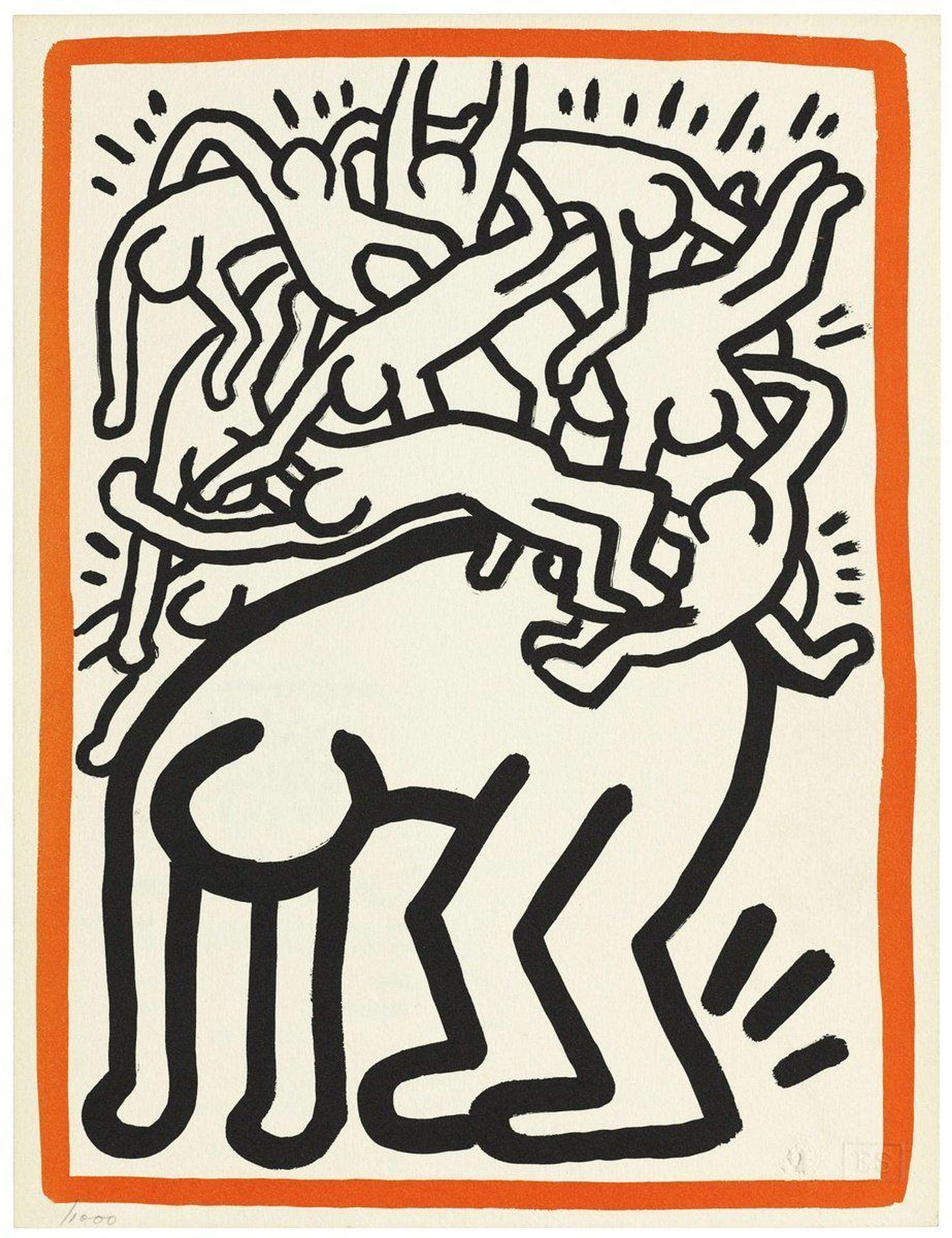

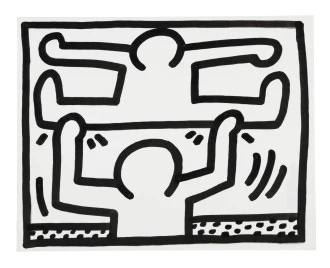

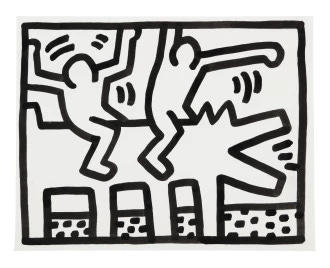

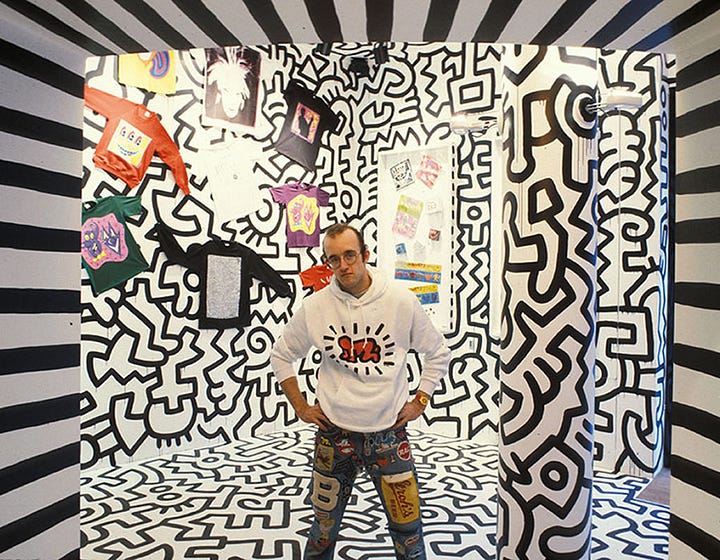

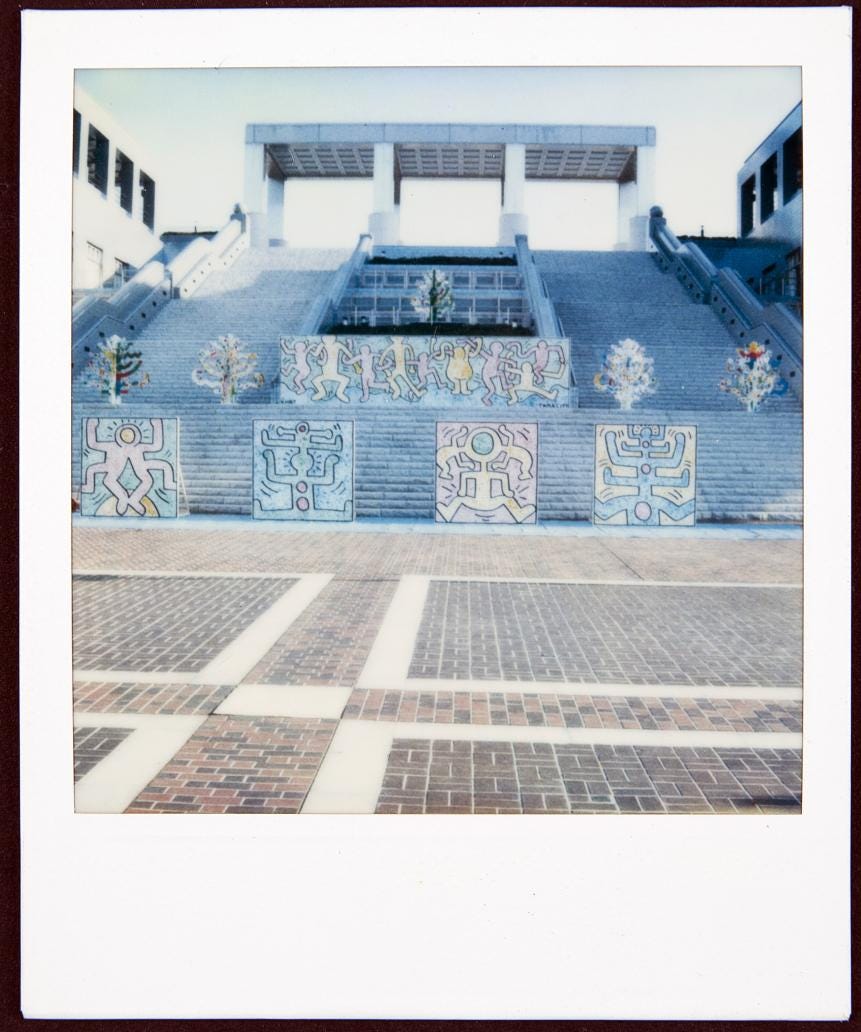

In his 1986 Pop Shop Drawings, Haring unleashes an effusive celebration of queer youth culture. Exuberant, sausage-limbed figures outlined in his signature black line stride across a stark white field alongside barking dogs, acrobats, and his iconic “best buddies.” By assembling these kinetic dancers and motifs into a unified series of drawings, Haring crafts a manifesto of joy and resilience; affirming the right of LGBTQ youth to love freely and live unburdened by fear.

Keith Haring’s first solo exhibition at Tony Shafrazi Gallery opened in October 1982, marking his formal transition from subway walls to the New York art market. Covered by CBS Evening News, the show moved over a quarter-million dollars’ worth of work in its opening days, despite Shafrazi’s intentionally modest price scale (drawings at $3,000; large paintings at $15,000) to keep Haring’s imagery accessible (en.wikipedia.org). Six years later, in December 1988, Haring returned to Shafrazi with what he himself called his most important exhibition to date; an affirmation of his meteoric rise from street-corner artist to international sensation (en.wikipedia.org).

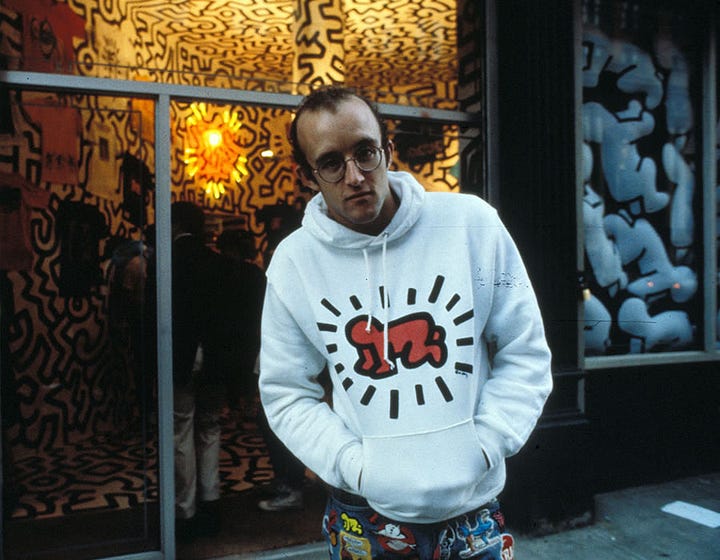

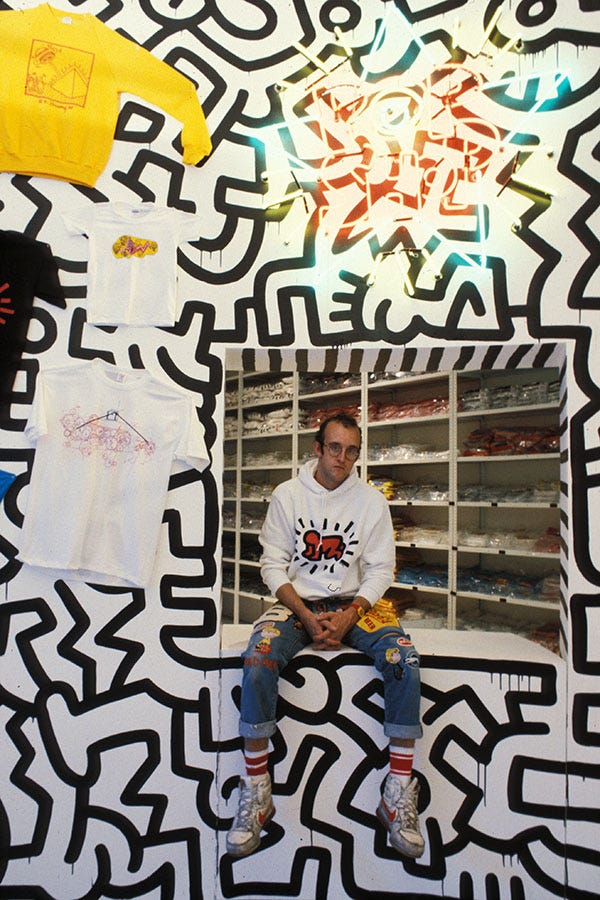

In the fall of 1986 Haring opened the Pop Shop in SoHo, retailing T-shirts, buttons, stickers, and various ephemera emblazoned with his icons. Critics decried the venture as commercial exploitation, but Haring maintained that affordability and accessibility were central to his mission: “Art should be for everyone.” By collapsing the distinctions between unique artwork and mass-produced object, the Pop Shop extended his dedication to democratizing art consumption.

Haring and Andy Warhol first crossed paths at a SoHo opening in 1982, where Warhol, drawn to Haring’s subway drawings, invited the younger artist into his pop-centric orbit. In 1986 they co-created Andy Mouse, a series of silkscreen prints that depicted Warhol as Mickey Mouse and inserted Haring’s animated figures into Warhol’s iconic motifs. This playful hybrid interrogated notions of celebrity, commercialization, and identity. Beyond the studio, the two shared nights at clubs like Paradise Garage, as Haring documented: “Andy and I danced to disco… he loved the energy.”

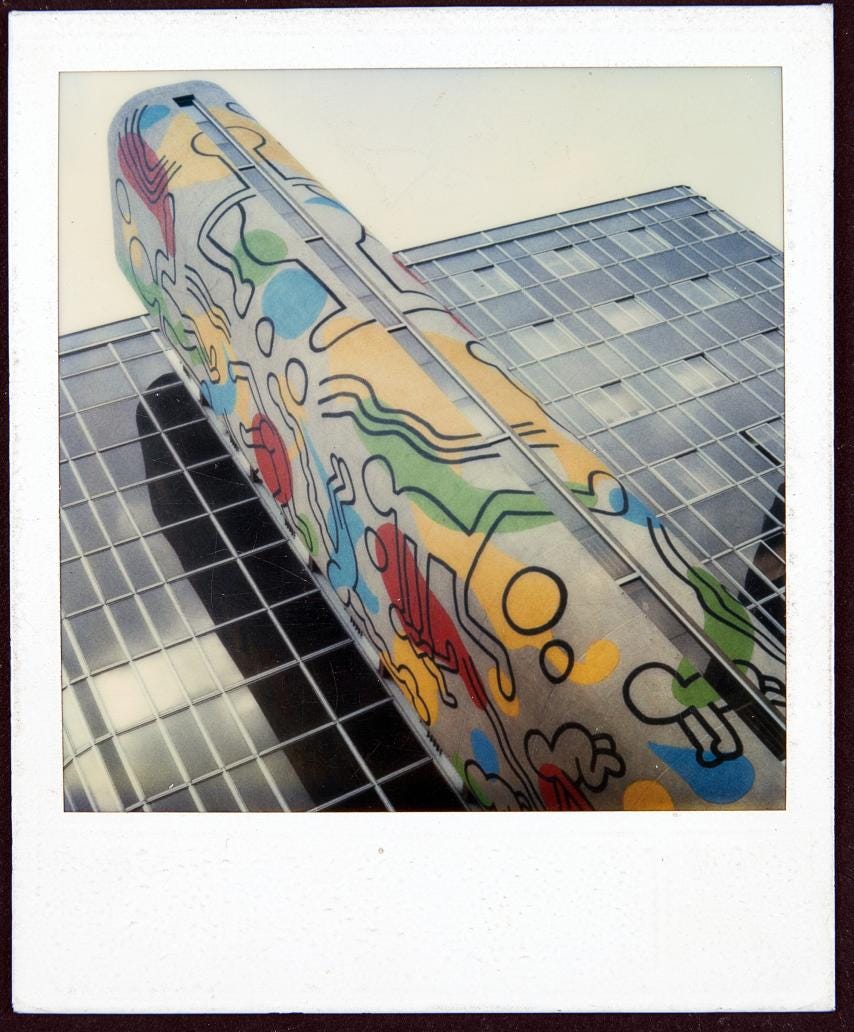

Across public and private contexts, Haring’s economy of line, thick contours, rhythmic repetition, and a restrained palette, ensured instant recognition. Drawing inspiration from graffiti, pop art, and cartoon traditions, he synthesized these sources into a visual language that was at once accessible and profoundly layered. Whether sketched in chalk tunnels or scaled onto civic murals, his forms communicated with universal clarity. Moreover, by extending his icons onto merchandise, he collapsed the divide between high art and mass culture, reaffirming that creative expression could and should be woven into everyday life.

Keith Haring died on February 16, 1990, from AIDS-related complications, but his visionary ethos endures. The Keith Haring Foundation, established shortly before his passing, continues to fund HIV/AIDS organizations and children’s programs, distributing millions each year. His imagery has permeated fashion, design, and street art worldwide, inspiring successive generations of queer artists such as David Wojnarowicz and Félix González-Torres, who similarly fuse personal narrative with political critique. In 2012 the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs launched the “Keith Haring Cities” program, commissioning his icons in public art projects from Tokyo to Rio, underscoring the timeless resonance of his calls for unity, activism, and love.

Keith Haring’s body of work remains a living testament to art’s power as activism. Through subway drawings, public murals, gallery canvases, and philanthropic ventures, he confronted the crises of his era, AIDS, racism, drug addiction, and social inequality, while celebrating queer identity, camaraderie, and joy. His friendship with Andy Warhol exemplified a cross-generational dialogue that enriched both artists’ practices. Today, Haring’s radiant lines continue to call us toward innocence, hope, and collective action, proving that the simplest marks can carry the deepest convictions.

References:

Buchhart, Dieter. Keith Haring: The Instant Painting. Prestel, 2014.

Deitch, Jeffrey. Keith Haring. Abrams, 1997.

Emmerling, Leonhard. Keith Haring: The Life and Work of an Icon. Thames & Hudson, 2004.

Gray, Jonathan. Andy Warhol: A Biography. HarperCollins, 2003.

Haring, Keith. Journals. Edited by Robert Farris Thompson, Viking, 1996.

Haring Foundation. About the Foundation. Keith Haring Foundation, https://www.haringfoundation.org/about. Accessed 24 Feb. 2025.

Jacob, Mary Jane. Public Art/Private Marriages: The Politics of Keith Haring’s Iconography. Art Journal, vol. 50, no. 3, 1991, pp. 32–39.

MoMA. Keith Haring: Projects. Museum of Modern Art Annual Report, 1982.

McShine, Kynaston. Keith Haring. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1991.

Neubert, Peter. Study of Site-Specific Mural: Keith Haring in Munich. Journal of Public Art, vol. 2, no. 1, 1988, pp. 10–15.

Riggs, Thomas. Keith Haring’s Activism Through Art. American Art Review, vol. 7, no. 2, 1994, pp. 56–63.

Shafrazi Gallery. Keith Haring: Untitled Exhibition. Tony Shafrazi Gallery Press Release, 1986.

Warhol, Andy, and Keith Haring. Andy Mouse: Experimental Screenworks. Andy Warhol Museum Archive, 1986.

Warhol Museum. Collaborative Print: Warhol & Haring. Exhibition Catalogue, 1987.

Some time we have to do a live talking with Kel about his experienced with Keith. We were just talking about him today, him handing out buttons as they would walk along the streets of NYC. He was shy but shameless.

To be handed one of his graphic buttons by the man himself? Epic.

He's always been a favorite. Reminds me of R Crumb comix in some ways.