Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988) emerged from Brooklyn’s streets to redefine late twentieth-century art by fusing graffiti’s raw immediacy with Neo-Expressionist urgency. Born to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother, his bilingual, multicultural upbringing informed the dense iconography of his canvases. While his contributions to Neo-Expressionism and street art have been widely celebrated, Basquiat’s bisexual and pansexual intimacies. and the coded queerness embedded in his work, remain underexamined.

Raised in LeFrak City, Basquiat absorbed Haitian Vodou symbols, Puerto Rican folklore, and Catholic imagery from an early age. The death of his mother in 1977 and subsequent estrangement from his father drove him to Manhattan’s underground, where he adopted the pseudonym SAMO to scrawl cryptic aphorisms across SoHo walls (Hoban 27). By 1980, venues such as Club 57 and the Mudd Club had become crucibles for queer performance, avant-garde music, and experimental art. Against the backdrop of AIDS hysteria and burgeoning gay rights activism, Basquiat navigated relationships with both men and women, including Suzanne Mallouk and, briefly, Madonna, prompting Mallouk to describe his “multichromatic sexuality,” an attraction that transcended binary definitions of gender (Hoban 114–18).

Basquiat’s oeuvre consistently places the body at the intersection of vulnerability, eroticism, and political struggle. His skeletal motifs, most famously in Untitled (1982), draw from European vanitas traditions and African diasporic funerary art, prefiguring queer communities’ confrontation with mortality during the early AIDS crisis (Mercer 148–50). When analyzed through Judith Butler’s theory of performativity, works such as Dustheads (1982) reveal their mask-like faces to function as drag-like enactments of queerness, destabilizing normative gender display through an ecstatic merging of figures (Butler 23–27). Similarly, Charles the First (1982) reclaims regal symbolism for Black and queer subjects: the recurrent three-pointed crown, which Basquiat employs to honor jazz icons, asserts a queered sovereignty that resists both colonial hierarchies and heteronormative power structures (Tate 49–52).

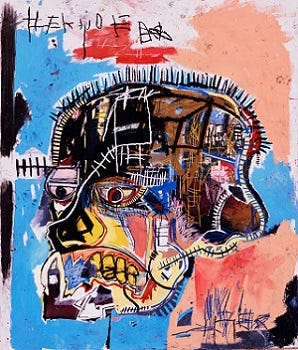

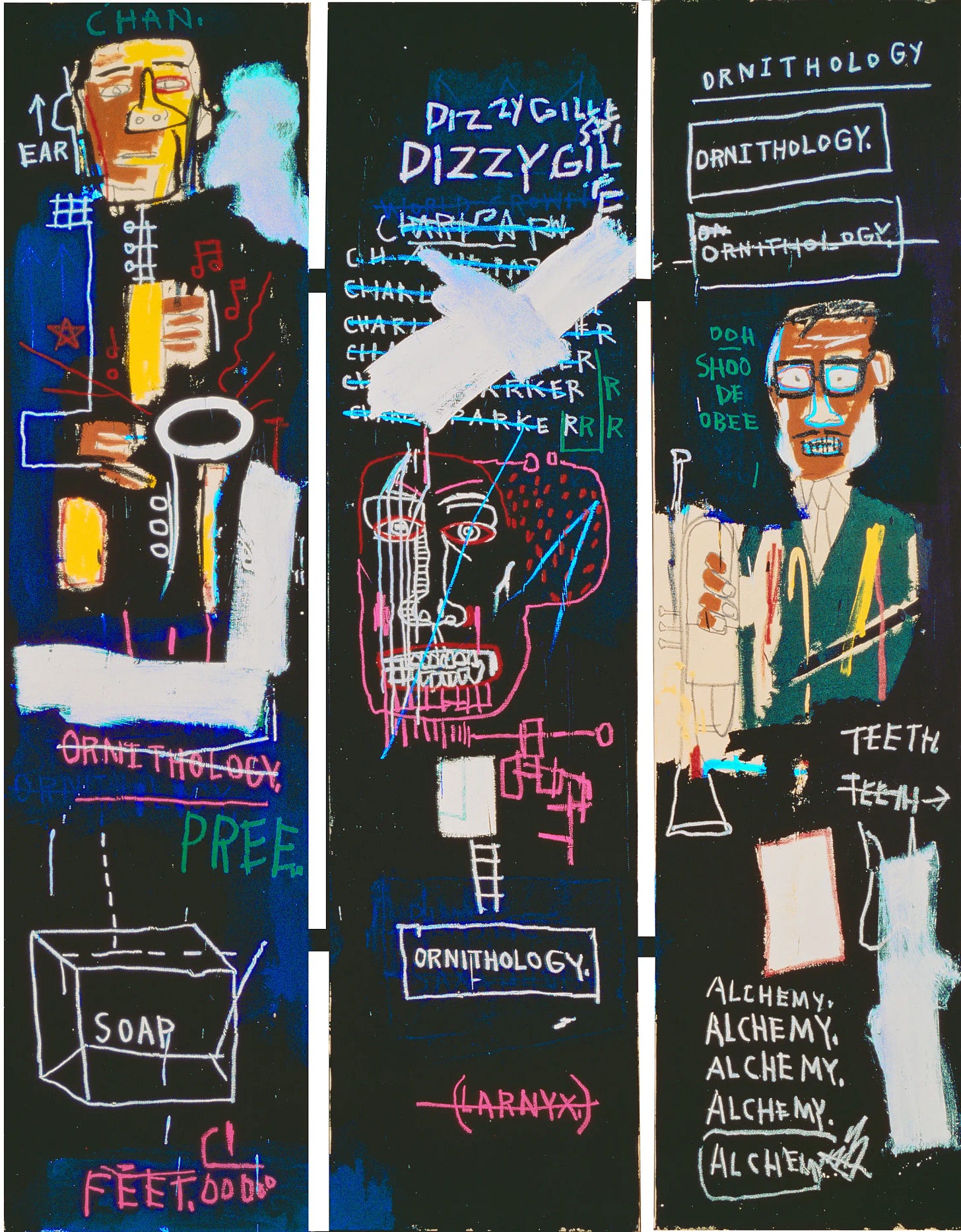

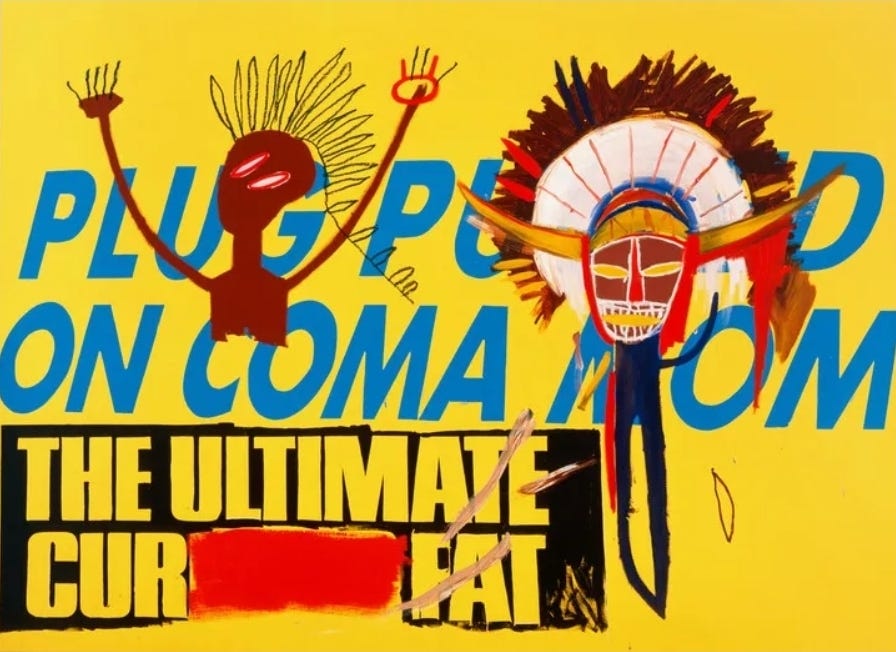

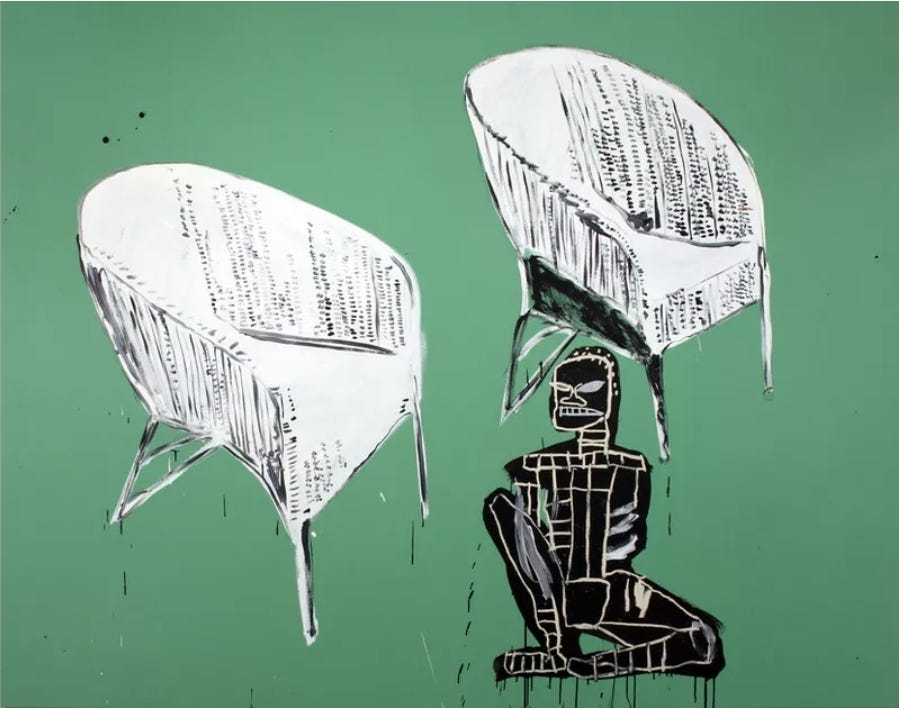

Across his career, Basquiat produced paintings that encode queerness in form and content. In Untitled (Skull) (1981/1982), a half-emerged cranium floats against a charged field of color; its drips and frenetic marks fuse street-tag immediacy with memento mori iconography, offering a pre-AIDS queer meditation on mortality (Mercer 150). Dustheads (1982) depicts two spectral figures painted in acid greens and fiery oranges, whose entwined forms enact an ecstatic fusion that Butler’s framework interprets as a performative masking of self and other (Butler 27). Shifting to reclaimed wooden slats in Flexible (1984), Basquiat portrays a gymnast-like figure in fluid arcs; the uneven wood grain amplifies gestural paint pools and splinters, symbolizing queer resilience amid heteronormative constraints (Cooper 63). Meanwhile, Horn Players (1983) interlaces musical notation, fragmented text, and dynamic figures across a triptych to evoke the syncopated visual rhythm of jazz, which Tate describes as a manifestation of queer temporalities; nonlinear, improvisational resistances to normative life scripts (Tate 49).

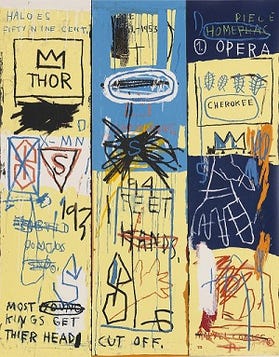

In Per Capita (1983), Jean-Michel Basquiat crafts a chaotic and layered composition where a large red rectangle, anchored by a bold, crown-like blue "M," is surrounded by fragmented drawings and cryptic text such as "ZEUS ME ZEUS" and "POISON SNAKES, 5 WOLF DOGS." This dense interplay of symbols and words indicts capitalism’s commodification of marginalized bodies, weaving together references to mythology, religion, and societal critique. Scholar bell hooks interprets this frenetic layering as a spectacle in which queer bodies are consumed by market forces, highlighting the painting’s commentary on exploitation within a capitalist framework (hooks 132). Returning to his street-art roots, Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump (1982) shows a scrappy youth and a skeletal canine erupting from a hydrant’s spray, the raw spray-paint outlines and jumbled text fragments recalling subway graffiti and punk zine aesthetics as Alt-institutional reclamations of art (hooks 138). In Hollywood Africans (1983), Basquiat crowns himself, Rammellzee, and Toxic, subverting media framing into an act of Afro-Futurist empowerment; Dieter Buchhart argues that this speculative reclamation projects Black subjects into technological futures (Buchhart 118).

Addressing systemic violence, Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981) portrays a Black officer wearing a caged helmet whose bars echo plantation fences; the background’s corporate logos implicate consumer culture in neocolonial oppression, positioning the work within Basquiat’s broader economic critique (Mercer 164). With Charles the First (1982), the skeletal homage to Charlie Parker is crowned and scrawled with the word “KING,” blending bebop syncopations with graffiti energy to assert jazz as a counter-narrative to Western hierarchies (Monson 77). Head (1983), monumental in scale, presents a mask-like visage in trembling lines and stark highlights; Hal Foster interprets this as an articulation of the “split subject,” in which Basquiat’s fractured identity becomes both trauma and creative source (Foster 89).

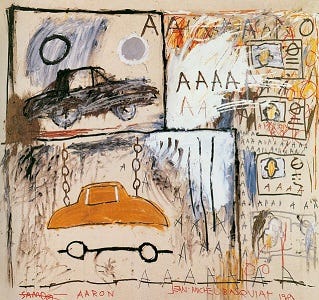

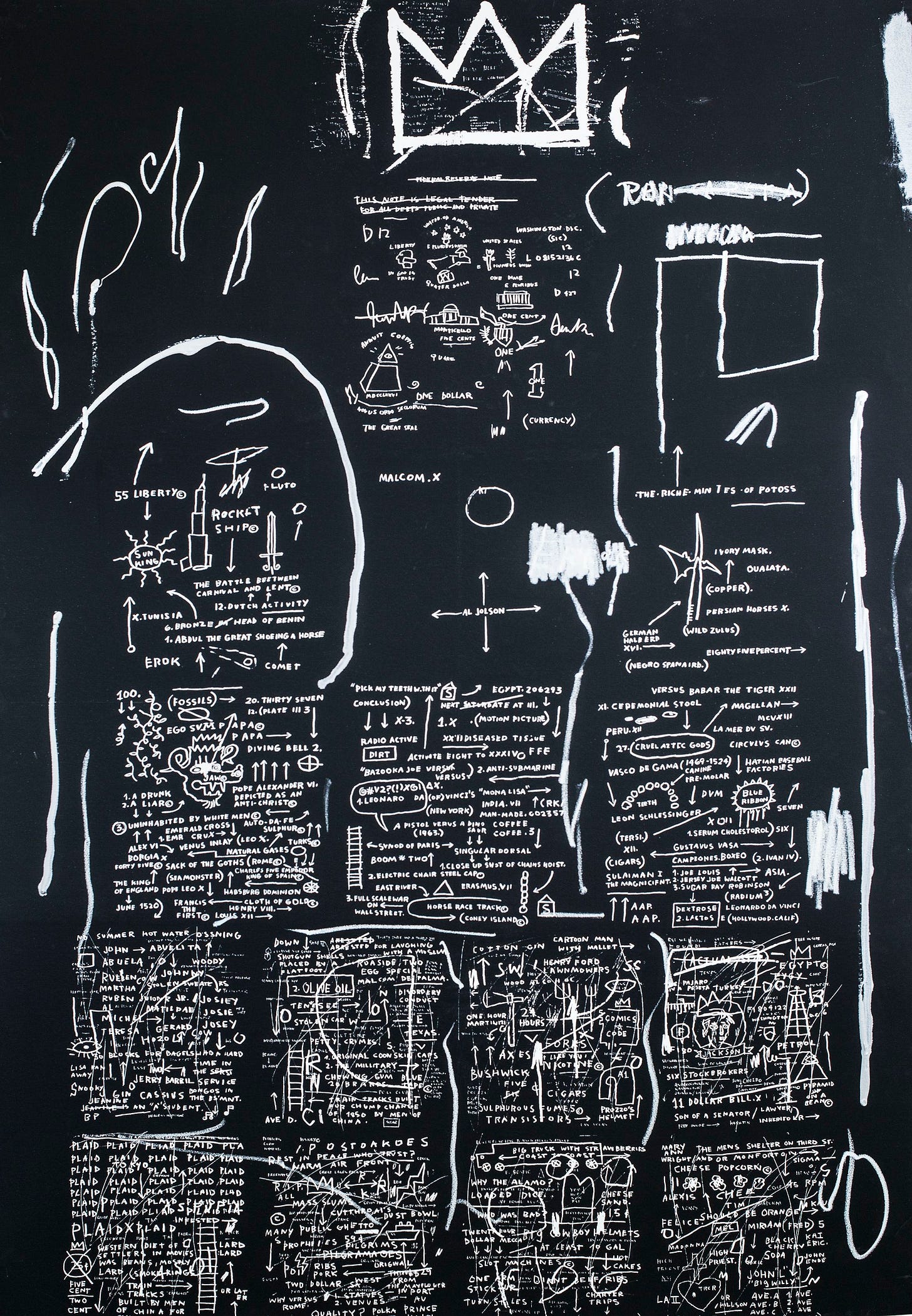

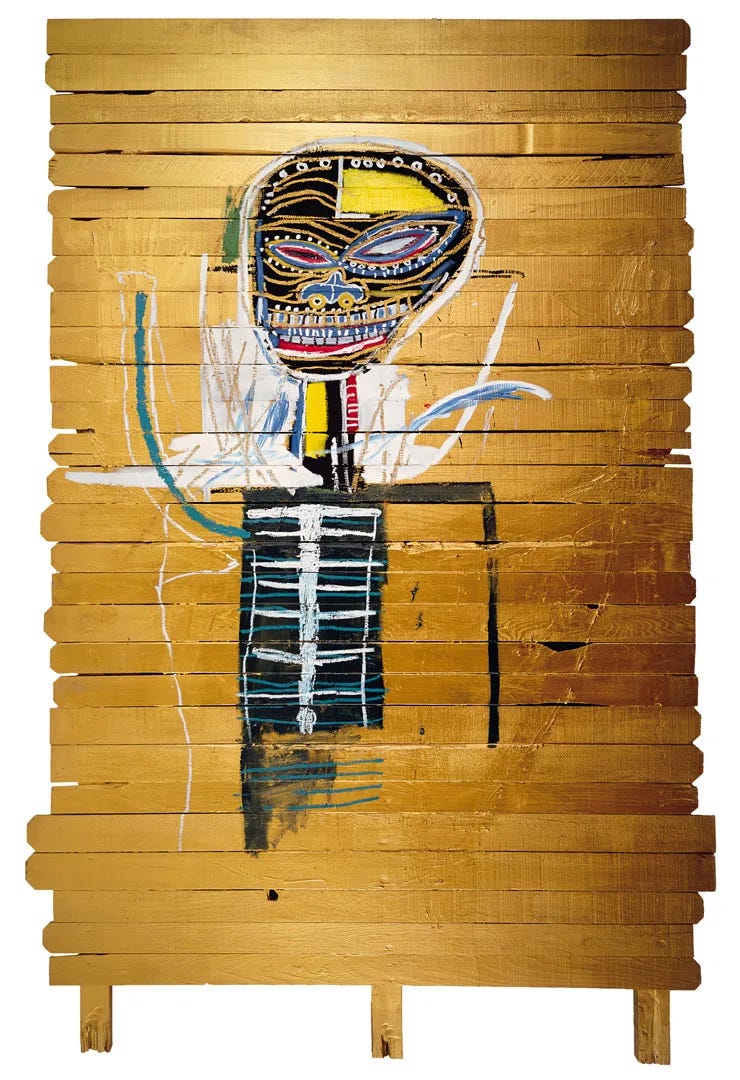

Early in his career, Cadillac Moon (1981) juxtaposes childlike figures and inscriptions across an expanse to explore American mobility’s mythos; James Flink reads the Cadillac motif as symbolizing both liberty and complicity in capitalist consumption (Flink 59). In Tuxedo (1982), is anchored by a deep black field, across which white text, symbols, and abstract sketches are dispersed with both spontaneity and deliberate intent. Dominating the upper register is Basquiat’s signature crown motif, immediately commanding the eye. Around this royal emblem, cryptic figures and inscriptions emerge; names of historical personalities, fragments of mathematical and scientific notation, and a variety of mysterious glyphs critiquing sartorial conformity; a technique he honed through studio exchange with Warhol (Adler 27). Drawing on West African oral traditions, Gold Griot (1983) presents a stylized, abstract figure set against a textured, golden background composed of wooden planks. The figure’s large, mask-like head, adorned with vibrant, expressive colors and patterns, including blue and white concentric shapes around the eyes, a wide toothy grin outlined in red, and a yellow patch with black lines atop the head, evokes the spirit of a Griot, a storyteller and keeper of history. The geometric body, with its rectangular torso marked by horizontal white lines suggesting a ribcage-like structure, serves as a vessel for these cultural narratives (Stoller 88).

In Untitled (Two Heads on Gold) (1982), two mask-like faces, rendered in dark brown with stark black and white accents, are set against a background that blends muted teal and earthy brown tones. The faces are characterized by large, hollow eyes with concentric circles and wide, toothy grins, surrounded by spiky, radiating lines that suggest wild hair or a crown. The rough, textured brushstrokes and urban color palette evoke a gritty, street-inspired aesthetic, while the dynamic, scribbled lines and abstract shapes infuse the composition with a chaotic energy; Jennifer Clement reads this diptych as Basquiat’s inner dialogue across temporal borders (Clement 95). Finally, a variant of Untitled (Skull) (1982) reappears with the cranium outlined in swift, gestural strokes against an “atmospheric void” of blue; Glenn Kaino observes that this void compels viewers to confront mortality’s specter amid the early AIDS crisis (MOCA LA Bulletin).

In 1982, Andy Warhol invited Basquiat into the Factory, where their collaborations fused Warhol’s silkscreen mechanics with Basquiat’s spontaneous marks, yielding a potent hybrid of pop detachment and social critique (Adler 27). Concurrently, Keith Haring’s calligraphic activism, epitomized by his Silence = Death imagery, inspired Basquiat to address systemic violence more overtly in his public murals (Saggese 160). Although critics debated Warhol’s commercialization versus Haring’s direct political messaging, Basquiat synthesized their strengths to forge a queer avant-garde that straddled street and studio realms (Buchhart 118).

Basquiat’s polyvalent imagery resonates alongside Robert Mapplethorpe’s frank explorations of male sexuality and Haring’s activist graffiti, yet his queerness remains encoded rather than confessional, resisting monolithic representation. Posthumous exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum (2005), Fondation Louis Vuitton (2017), and Tate Modern’s 2021 retrospective have progressively foregrounded his bisexual narrative, anchoring him as a foundational queer artist of color (Buchhart; Tate Modern brochure; Saggese 176).

Basquiat’s synthesis of graffiti, art-historical allusion, and socio-political critique informs generations of queer artists of color, among them Rashid Johnson, Mickalene Thomas, and Tschabalala Self, who cite his work as a template for intertwining race, gender, and sexuality (Mercer 174). Initiatives such as MOCA LA’s 2022 symposium “Basquiat & the Body” and digital queer chronology archives ensure that his bisexual lens remains integral to ongoing scholarly discourse (MOCA LA Bulletin).

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art embodies queerness as layered, performative, and resistant to singular narratives. Through fluid intimacies, collaborative inventiveness, and radical reinvention of symbols, he forged a visual language transcending boundaries of race, sexuality, and class. As contemporary studies continue to excavate his bisexual identity, Basquiat’s oeuvre stands as a testament to the transformative power of queered storytelling in art.

References:

Adler, Alexis. Working with Basquiat: Warhol Collaborations. ART Press, 1992.

Adler, Alexis. Personal interview. 27 Mar. 1992.

Bell Hooks. Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. Art Journal, vol. 58, no. 4, 1999, pp. 130–35.

Buchhart, Dieter. Basquiat: Boom for Real. Fondation Louis Vuitton, 2017.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. Routledge, 1993.

Cooper, Alisa. Material Matters: Conserving Flexible. MOCA Bulletin, vol. 12, no. 3, 2018, pp. 59–64.

Clement, Jennifer. Dialogues of Duality. Artforum, vol. 42, no. 6, June 2004, pp. 92–97.

Flink, James. The Automobile Age. MIT Press, 1990.

Foster, Hal. Split Identity in Basquiat’s Head. October, no. 123, Spring 2008, pp. 85–94.

Hoban, Phoebe. Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art. Viking, 1998.

Hobbs, Allyson. Trauma and Expression in Contemporary Art. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

hooks, bell. Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. Art Journal, vol. 58, no. 4, 1999, pp. 130–35.

Lepecki, André. Archive and Embodiment. Routledge, 2016.

Mercer, Kobena. Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies. Routledge, 1994.

Menil Conservation Report. Head Restoration Dossier. The Menil Collection, 2019.

Monson, Ingrid. Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

MOCA LA Bulletin. Untitled (Skull) and Mortality. Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, vol. 8, no. 2, 2018.

Saggese, Jordana Moore. Reading Basquiat: Exploring Ambivalence in American. University of California Press, 2014.

Stoller, Paul. Sensuous Scholarship. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

Tate Modern. Life After Basquiat. Exhibition brochure, 2021.

Tate, Greg. Basquiat’s Beat: Jazz and Neo-Expressionism. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Basquiat and the Blues. Prestel, 2022.

Hmmm...never looked at J-MB in quite this way. Always just loved his compositions, subject matter, frenetic color. Just reserved the Hoban book at the library for starters.

Before I go any further do not let me forget to tell you my story of going to Toxic’s Italian ‘Villa’ in 2018 and oh yes… it was 100 percent toxic.