Color, Culture, and Plaster: Decoding the Fascinating World of Frescoes

#FrequentlyAskedQuestions #FrescoFriday

Over the past couple of years, I have had the pleasure of sharing my passion for frescoes through a weekly series titled "FrescoFridays" on platforms such as Facebook and Threads. This initiative has provided a space to explore the vibrant history, techniques, and cultural significance of fresco painting, which has captivated audiences eager to learn about one of the most enduring and dynamic forms of artistic expression. The concept of fresco painting, in which pigments are applied to wet plaster, has a history stretching back thousands of years. As I have shared through these weekly posts, frescoes not only offer a glimpse into the rich traditions of art, but also reflect the complex histories and beliefs of the cultures that produced them.

A fresco, at its core, is a mural painting technique where pigments are applied to fresh, wet plaster. The process results in a bond between the pigment and the wall, allowing the artwork to become an integral part of the structure itself. Fresco painting has been practiced in various civilizations from ancient Egypt to contemporary Mexico, with each cultural tradition shaping the medium in unique ways. Its ability to endure for centuries has made it one of the most fascinating and enduring methods of artistic expression, and understanding its history, techniques, and impact on culture allows for a deeper appreciation of the medium's lasting legacy.

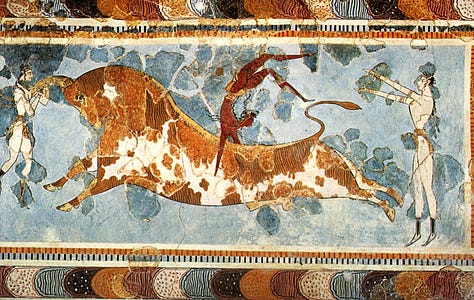

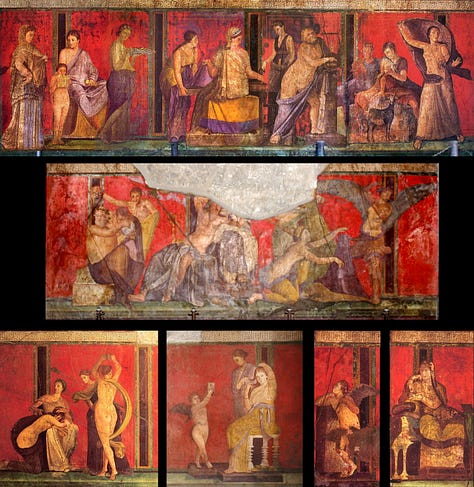

The origins of fresco painting can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where it was used not only as a decorative art but also as a means of conveying religious and political messages. The term "fresco" comes from the Italian word "affresco," which means "fresh," referring to the technique of applying pigments onto wet lime plaster. This method ensures that the pigments are absorbed by the plaster as it sets, creating a bond that makes the artwork a permanent part of the wall. Fresco painting can be traced to ancient Egypt, where tombs and temples were decorated with colorful scenes that depicted daily life, religious rituals, and divine figures (Dunn 2007). Some of the earliest examples of fresco painting come from the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete, with the Palace of Knossos, dating from the 15th century BCE, providing some of the most important surviving frescoes from the period. The Minoans are known for their vibrant and dynamic frescoes, which often depicted natural scenes such as dolphins, lilies, and birds, as well as religious and ceremonial subjects (Marinatos 1993). Roman fresco painting, particularly in Pompeii and Herculaneum, provides some of the best-preserved examples of ancient frescoes. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE preserved the cities in ash, allowing archaeologists to discover detailed frescoes that once adorned the homes of the Roman elite. These frescoes depict mythological themes, landscapes, and intricate geometric patterns, demonstrating the Roman mastery of perspective, space, and color (Ling 1991). The Roman fresco technique often used buon fresco (true fresco), in which pigments were applied to wet plaster, creating a durable bond between the paint and the wall. This method allowed the paintings to withstand the test of time.

Fresco painting involves two primary techniques: buon fresco and fresco secco. Buon fresco (true fresco) is the method in which pigment is applied to freshly mixed lime plaster. As the plaster sets, the pigment bonds with the wall, making the artwork an enduring part of the surface. This technique requires the artist to work quickly before the plaster dries, resulting in a high level of precision and expertise. One of the main benefits of this technique is that the pigment becomes embedded in the plaster, making the artwork a permanent part of the wall. The buon fresco method is seen in some of the most famous frescoes in art history, including Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling. Painted between 1508 and 1512, the Sistine Chapel ceiling represents one of the highest achievements of buon fresco painting, with Michelangelo’s skillful use of color, perspective, and anatomy demonstrating the medium’s potential to express complex human themes (Hibbert 1996). Fresco secco (dry fresco), in contrast, involves applying pigments to dry plaster. While this technique allowed the artist more time to complete the work, it lacked the permanence of buon fresco, as the pigment did not bond chemically with the plaster. Fresco secco was often used for finer details or intricate decorative elements, and it is common for the two techniques to be combined in one work. For example, an artist may use buon fresco for the larger sections of the mural and fresco secco for the more delicate touches and final details.

During the Italian Renaissance, fresco painting reached its peak, and many of the most iconic works of Western art were created using this technique. The Catholic Church, wealthy patrons, and civic authorities commissioned frescoes to decorate public buildings, churches, and palaces, and these works often carried political, religious, or philosophical significance. Michelangelo’s frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, commissioned by Pope Julius II, are among the most celebrated examples of Renaissance fresco painting. The ceiling features scenes from the Book of Genesis, including the iconic "Creation of Adam," which is perhaps the most famous image in Western art. Michelangelo’s mastery of anatomy, his innovative use of space, and his dramatic depiction of biblical themes made this fresco cycle an unparalleled achievement (Hibbert 1996). Raphael’s frescoes in the Vatican Rooms, particularly the School of Athens, are another hallmark of Renaissance fresco painting. Raphael’s use of perspective and his representation of ancient Greek philosophers in a harmonious and orderly composition reflected the humanist ideals of the Renaissance. The fresco, which includes figures such as Plato and Aristotle, embodies the intellectual and philosophical aspirations of the period (Robinson 2006). Raphael’s frescoes, along with those of Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, played a key role in elevating fresco painting to a medium capable of conveying complex intellectual, philosophical, and theological concepts. Frescoes during the Renaissance were not only works of art but also tools of political propaganda. The Stanza della Segnatura, Raphael’s frescoes commissioned by Pope Julius II, were intended to affirm the Church’s authority and power. The frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura depict religious, philosophical, and legal themes, and their grand scale and intricate composition reflect the political aspirations of the papacy during this period.

Although fresco painting declined after the Renaissance, it continued to be used throughout the Baroque period, often with a greater emphasis on drama and emotional intensity. Artists such as Peter Paul Rubens and Caravaggio used fresco techniques to create dynamic, elaborate compositions in churches and palaces. In particular, Rubens’ frescoes in the Banqueting House in London are exemplary of Baroque fresco painting, with their sweeping compositions and rich colors. The 20th century saw a resurgence of fresco painting, particularly in Mexico, where artists like Diego Rivera used the medium as a tool for political and social commentary. Rivera’s murals, such as those at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, depict the struggles of the working class and indigenous populations, and they reflect the social and political climate of the time. Rivera’s frescoes revitalize the mural tradition and emphasize the power of art to address issues of social justice (Tufte 2006).

The preservation of frescoes is an ongoing challenge, as the medium is highly susceptible to environmental factors such as humidity, temperature fluctuations, and physical damage. Frescoes are often found in public spaces or difficult-to-access locations, making them vulnerable to deterioration. Efforts to conserve frescoes include cleaning, stabilization, and digital restoration. The goal is to preserve the integrity of the original artwork while allowing for the long-term enjoyment of these cultural treasures.

Fresco painting remains a powerful and enduring form of artistic expression, with a history that spans thousands of years. From its ancient origins to its Renaissance triumph, frescoes have captured the imagination of artists and audiences alike, reflecting the social, political, and intellectual currents of their time. Today, frescoes continue to inspire artists and art lovers, ensuring that this ancient technique remains a vital part of our cultural heritage. As we continue to explore frescoes through initiatives like my weekly "FrescoFridays" series, we gain a deeper appreciation for the medium’s ability to convey beauty, meaning, and complexity. Frescoes are more than just murals; they are windows into the hearts and minds of the people who created them, and their legacy endures as a testament to the power of art.

References:

Dunn, Marilyn. The Painted Tombs of Roman Africa: The Later Inscriptions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Hibbert, Christopher. Michelangelo: The Complete Paintings, Sculptures, and Architecture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Ling, Roger. Roman Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Marinatos, Nanno. Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image, and Symbol. Columbia University Press, 1993.

Robinson, Frank. Raphael: The Invention of the High Renaissance. New York: Harper & Row, 2006.

Tufte, Edward R. Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press, 2006.

One of the most memorable fresco scenes in a movie for me was in The English Patient. It really stick with me because of one of my own fresco discovery moments when the church of Santa Croce was closed to the public but I happened to get inside. They were doing some repair work on the frescoes by Agnolo Gaddi presenting stories of the Saints Antonio Abate, Giovanni Battista, Giovanni Evangelista and Nicola di Bari. The particular wall to the right of the impression of painted tile is something I have reproduced multiple times for commissions.

I did not realize Caravaggio only left us one fresco! What a grim reality 😐